ANZUS at 70: Remembering September 11—a prime minister looks back

This post is an excerpt from the new ASPI publication ANZUS at 70: the past, present and future of the alliance, released today. Over the next few weeks, The Strategist will be publishing a selection of chapters from the book.

I first met President George W Bush on 10 September 2001. I had travelled to Washington to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the ANZUS Treaty. As part of that observance, I was presented with the ship’s bell of USS Canberra. The US Navy warship was named in honour of HMAS Canberra, which was lost in the Battle of Savo Island while protecting American marines landing on Guadalcanal.

What followed the attack the next day on September 11 was to demonstrate the strength of the relationship between our two countries. Twenty years after that day, and 70 years after the signing of the security treaty, this is an important occasion to reflect on the alliance’s history, future and enduring significance. This is a relationship forged in the Indo-Pacific, strengthened during the War on Terror, and permanently part of our future security.

Being in Washington at the time of those attacks had a powerful effect on me. Earlier that day, I had walked past many of Washington’s memorials on what was a beautiful autumn morning. Just one hour before the attacks commenced, I walked past the Lincoln Memorial; the statue’s clenched fist represented that president’s resolve to see through a war for freedom. Later that day, I wrote the following letter to President Bush:

Dear Mr President. The Australian Government and people share the sense of horror experienced by your nation at today’s catastrophic events and the appalling loss of life. I feel the tragedy even more keenly being here in Washington at the moment.

In the face of an attack of this magnitude, words are always inadequate in conveying sympathy and support. You can however be assured of Australia’s resolute solidarity with the American people at this most tragic time.

My personal thoughts and prayers are very much with those left bereaved by these despicable attacks upon the American people and the American nation.

On the morning of the attack, I had a scheduled news conference just after 9 am to speak about my visit and other domestic issues of the day. Before the conference, my media adviser calmly informed me a plane had hit one of the towers at the World Trade Center. He returned 10 minutes later, banging on my door to tell me another plane had hit the other tower. While the news conference was in progress, the third plane was driven into the Pentagon. After the news conference had finished, we pulled back the curtains to see smoke rising above Washington.

The sheer scale of the death and destruction was extraordinary, especially during peacetime. The surprise attack had killed more people than Pearl Harbor, though this time the targets were innocent civilians. Being in the US, I shared and observed the shock, disbelief and anger of the American people. That day changed the psychology of the United States profoundly.

Despite having the most powerful military the world has ever known, Americans have long felt vulnerable. They worry about being friendless and alone. The day after the attack, Janette and I, accompanied by Australia’s then ambassador to the US, Michael Thawley, his wife and our security detail, sat in an empty public gallery of the US House of Representatives. We attended to convey the sympathy and support of the Australian people. The speaker drew attention to my presence, and I was deeply moved to receive a standing ovation. It was clear that Australia stood by the US and that we would assist in the retaliation against those responsible.

September 11 had been an attack on the American way of life and, because of our shared values, it was also therefore an attack on our way of life. Before departing Andrews Air Force Base near Washington to return to Australia, I promised that ‘Australia would provide all support that might be requested of us by the United States in relation to any action that might be taken.’ Being in Washington when the attacks occurred led to my immediate commitment to offer support to the President. On the journey back to Australia, Alexander Downer and I agreed that, subject to cabinet approval, the ANZUS Treaty should be invoked.

The attacks on America’s commercial heart and its capital clearly constituted an attack upon the metropolitan territory of the US within the meaning of articles IV and V of the ANZUS Treaty. More than that, our commitment was a statement of friendship and solidarity—an expression that America and Australia stand together in a common cause. As I said in my address to parliament after my return to Australia:

If that treaty means anything, if our debt as a nation to the people of the United States in the darkest days of World War II means anything, if the comradeship, the friendship and the common bonds of democracy and a belief in liberty, fraternity and justice mean anything, it means that the ANZUS Treaty applies and that the ANZUS Treaty is properly invoked.

The alliance isn’t based on the ANZUS Treaty alone, or aimed against any other countries. It’s based firmly on a shared history and world view. This results in us having similar values and interests. In the past, this has been demonstrated by the numerous occasions when we have fought alongside each other, from World War I to Afghanistan. Now it’s most evident in issues relating to technology, human rights and our commitment to the stability of the region.

Before arriving in Washington, I believed that because of the end of the Cold War there was a danger the alliance might in time be taken for granted. My four hours with President Bush on 10 September were the beginning of my friendship with him, as well as many other partnerships that would develop following September 11. Although our military and intelligence services have long had close associations, the campaigns we have fought alongside each other undoubtedly strengthened those bonds.

Our forces are now more accustomed to working together and are more interoperable than before. The posting of Australian service men and women to the Pentagon and various other joint commands has reinforced this. So, too, our longstanding intelligence-sharing agreements, along with our privileged access and contribution to those arrangements, have so far prevented further attacks on our countries. The trust and respect which have developed between our national security professionals, as a result of working so closely together, particularly over the past 20 years, complements the text of the ANZUS Treaty.

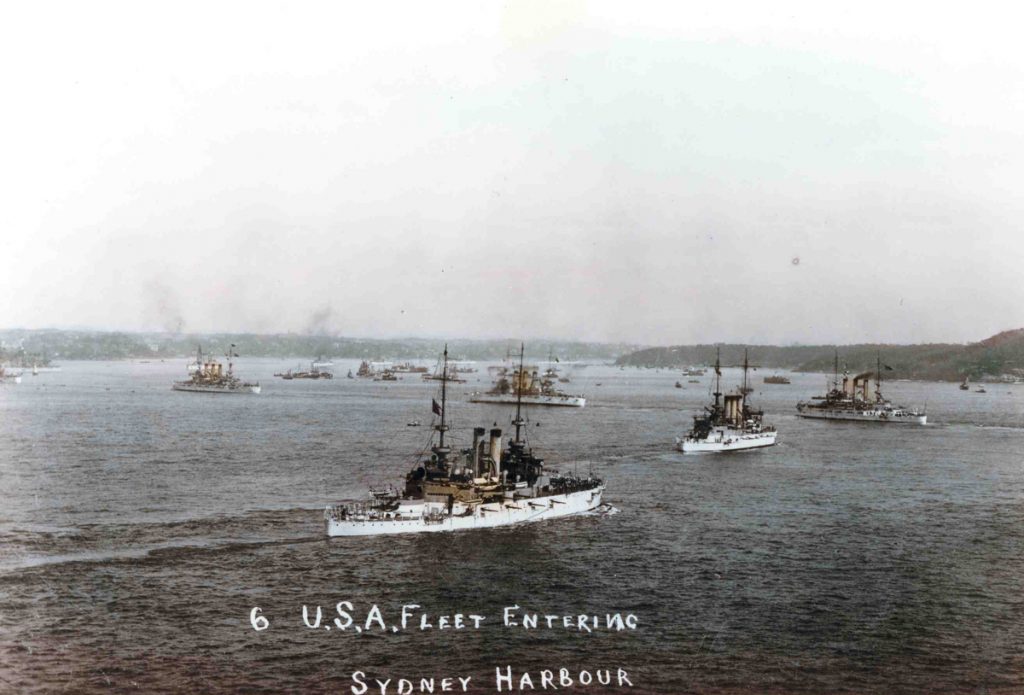

While much of our joint efforts in recent years has been focused on the Middle East, ANZUS has always been centred on the Indo-Pacific. With renewed interest and competition in the region, it’s worth remembering HMAS Canberra’s service and sacrifice at Guadalcanal which was honoured on 10 September 2001. That campaign, led by the US, followed by the Battle of the Coral Sea and the Battle of Midway, marked the Allies’ successful transition to offensive operations against Japan.

In time, that would win the war in the Pacific and secure the safety of Australia.

The alliance endures because of our shared history, values and interests. Seventy years after the signing of the ANZUS Treaty, it continues to be a force for stability in the region.