British public opinion on foreign policy: President Trump, Ukraine, China, Defence spending and AUKUS

Results snapshot

President Trump

- Britons support an open and engaged foreign policy role for the United Kingdom. In light of the re-election of President Donald Trump, 40% believe Britain should continue to maintain its current active level of engagement in world affairs, and 23% believe it should play a larger role.

- Just 16% of Britons support a less active United Kingdom on the world stage.

- When asked what Britain’s response should be if the United States withdraws its financial and military support from Ukraine, 57% of Britons would endorse the UK either maintaining (35%) or increasing (22%) its contributions to Ukraine. One-fifth would prefer that the UK reduces its contributions to Ukraine.

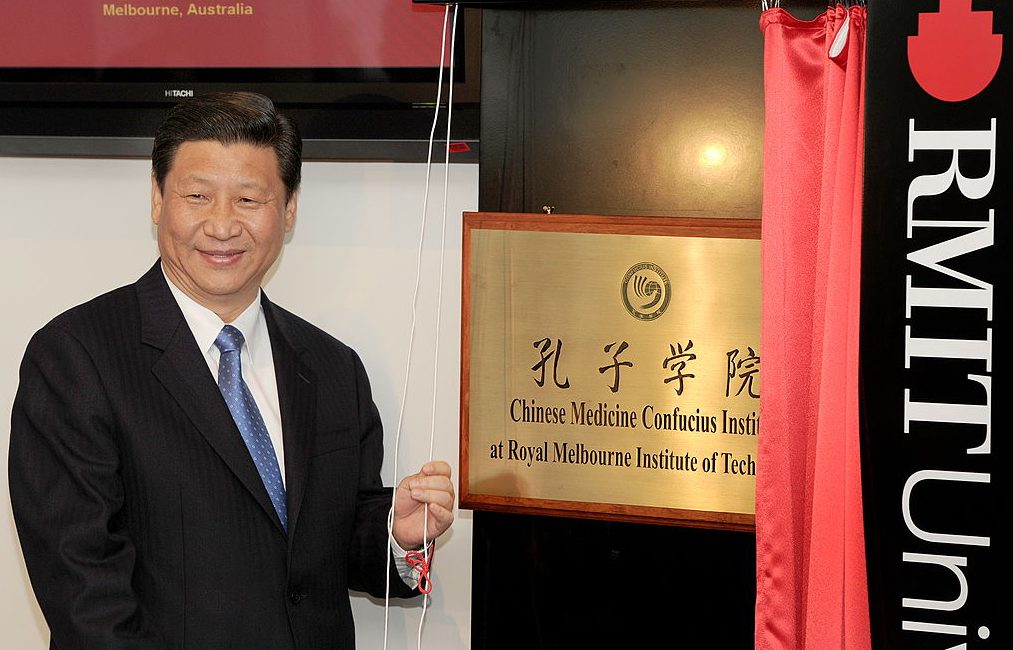

UK–China relations

- Just a quarter (26%) of Britons support the UK Government’s efforts to increase engagement with China in the pursuit of economic growth and stabilised diplomatic relations.

- In comparison, 45% of Britons would either prefer to return to the more restricted level of engagement under the previous government (25%) or for the government to reduce its relations with Beijing even further (20%).

- A large majority of Britons (69%) are concerned about the increasing degree of cooperation between Russia and China. Conservative and Labour voters share similarly high levels of concern, and Britons over 50 years of age are especially troubled about the trend of adversary alignment.

Defence and security

- When asked whether the UK will need to spend more on defence to keep up with current and future global security challenges, a clear two-thirds (64%) of the British people agree. Twenty-nine per cent of Britons strongly agree that defence spending should increase. Just 12% disagree that the UK will need to spend more.

- The majority of Britons believe that collaboration with allies on defence and security projects like AUKUS will help to make the UK safer (55%) and that partnerships like AUKUS focusing on developing cutting-edge technologies with Britain’s allies will help to make the UK more competitive towards countries like China (59%).

- Britons are somewhat less persuaded that AUKUS will succeed as a deterrent against Chinese aggression in the Indo-Pacific, although the largest group of respondents (44%) agree that it will.

Brief survey methodology and notes

Survey design and analysis: Sophia Gaston

Field work: Opinium

Field work dates: 8–10 January 2025

Weighting: Weighted to be nationally and politically representative

Sample: 2,050 UK adults

The field work for this report was conducted by Opinium through an online survey platform, with a sample size of 2,050 UK adults aged 18 and over. This sample size is considered robust for public opinion research and aligns with industry standards. With 2,000 participants, the margin of error for reported figures is approximately ±2.3 percentage points at a 95% confidence level. Beyond this sample size, the reduction in the margin of error becomes minimal, making this size both statistically sufficient and practical for drawing meaningful conclusions with reliable representation of the UK adult population. For the full methodological statement, see Appendix 1 of this report.

Notes

- Given the subject matter of this survey, objective and impartial contextual information was provided at the beginning of questions. There are some questions for which fairly substantial proportions of respondents were unsure of their answers. All ‘Don’t knows’ are reported.

- The survey captured voters for all political parties, and non-voters; however, only the findings for the five largest parties are discussed in detail in this report, with the exception of one question (6C), in which it was necessary to examine the smaller parties as the source of a drag on the national picture. The five major parties discussed in this report are the Conservative Party, the Labour Party, the Liberal Democrats, Reform (formerly the Brexit Party and UKIP), and the Green Party.

- This report also presents the survey results differentiated according to how respondents’ voted in the 2016 referendum on the UK’s membership of the European Union, their residency within the UK, their age, their socio-economic status, and whether they come from White British or non-White British backgrounds. The full methodological notes are found at the end of the report.

- Some of the graphs present ‘NET’ results, which combine the two most positive and two most negative responses together – for example, ‘Significantly increase’ and ‘Somewhat increase’ – to provide a more accessible representation of the balance of public opinion. These are presented alongside the full breakdown of results for each question for full transparency.

Introduction

There’s no doubt that 2025 will be a consequential year in geopolitical terms, with the inauguration of President Donald Trump marking a step-change in the global role of the world’s largest economy and its primary military power. The full suite of implications for America’s allies is still emerging, and there will be opportunities for its partners to express their agency or demonstrate alignment. For a nation like the United Kingdom, whose security and strategic relationship with the United States is institutionally embedded, any pivotal shifts in American foreign policy bear profound ramifications for the UK’s international posture. The fact that such an evaluation of America’s international interests and relationships is taking place during a time in which several major conflicts – including one in Europe – continue to rage, only serves to heighten anxieties among policy-makers and citizens alike.

Public opinion on foreign policy remains an understudied and poorly understood research area in Britain, due to a long-held view that the public simply conferred responsibility for such complicated and sensitive matters to government. Certainly, many Britons don’t possess a sophisticated understanding of the intricacies of diplomatic and security policy. However, they do carry strong instincts, and, in an internationalised media age, are constantly consuming information from a range of sources and forming opinions that may diverge from government positions.

The compound effect of a turbulent decade on the international stage has made Britons more perceptive to feelings of insecurity about the state of the world, which can be transposed into their domestic outlook. At the same time, their belief in the efficacy of government to address international crises, or their support for the missions being pursued by government, isn’t guaranteed. This creates a challenging backdrop from which public consent can be sought for the kind of bold and decisive actions that may need to be considered as policy options in the coming months and years.

This study provides a snapshot of the views of British citizens at the moment at which President Donald Trump was inaugurated for a second time. It shows a nation which, overall, continues to subscribe to clear definitions of its friends and adversaries, carries a sense of responsibility to Ukraine, and greets the rise of a more assertive China with concern and scepticism. Underneath the national picture, however, the data reveals some concerning seeds of discord and divergence among certain demographic groups and political parties. The UK Government must build on the good foundations by speaking more frequently and directly to the British people about the rapidly evolving global landscape, and making the case for the values, interests, and relationships it pursues.

Sophia Gaston

March 2025

London