Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

As nations in the Indo-Pacific become stronger economically and militarily, Australia needs a potent air force with a sharp-enough technical and tactical edge and ‘information warfare’ skills to defeat potential adversaries, air force chief Leo Davies has warned.

Opening the 2018 Air Power Conference in Canberra today, Air Marshal Davies noted that ‘we live in an age of disruption’. He said the shift of the geostrategic centre from the North Atlantic and Europe to the Indo-Pacific was the most significant shift in the global balance of power since the end of World War II.

Describing the impact of ‘air power in a disruptive world’, Air Marshal Davies said the information and communications revolution, the global increase in economic development, economic linkages and interdependencies, and competing forms of political and ideological movements had made the early 21st century a more dynamic strategic environment. Nowhere was this more evident than in the Indo-Pacific.

This unprecedented sharing of economic wealth and technical development meant more players—states, actors, businesses, communities—could exert influence, he said. ‘This means that sometimes these disruptors cause friction. And this friction requires management: shaping where necessary, but certainly influencing and—at times—direct action.’

‘More nations are investing in high-end warfighting capabilities, challenging what historically had been a Western advantage,’ Davies said. The rate of change in the region was faster than at any other time in history and the convergence of these trends was creating a new set of national security challenges.

Prosperity had enabled nations throughout the region to invest significantly in their militaries—a legitimate response aimed at protecting their interests. They had easy and affordable access to sophisticated technologies, enabling pre-industrial societies to leap straight to the digital age, bypassing industrial development. The impact of economic power would become even more pronounced as military power grew to match.

The air force chief said air power’s reach, speed and precision remained important elements of a nation’s defence strategy. ‘Investments in stealth, networks, ISR and precision weapons are no longer a guarantee of capability overmatch. We now need to seek alternate solutions to reinstate a military superiority.’

Over 20 years, Asia’s share of global manufacturing had increased from around 30% to over 50%, and rising economic powers would continue that transformation. The United States now faces challenges that are driving a refocus of its foreign policy.

The new US National Defense Strategy identified the re-emergence of long-term, strategic competition with ‘revisionist powers’ as its principle priority, Air Marshall Davies said. ‘This is a shift away from its more recent focus on asymmetric warfare—including counter-terrorism operations—and the maintenance of peace and order in an otherwise relatively stable global environment.’

He said this new power balance was emboldening some states to challenge the rules-based order. ‘Terrorists and organised crime have always looked for ways to get around the system. We are used to them not playing by the rules. But now some states are also looking to operate in the grey zone, exploiting the vulnerabilities of free societies, markets and global communications.’

Air Marshal Davies said the 2016 Defence White Paper had committed almost $100 billion to RAAF air power systems. ‘This will not just bring into service new platforms, but also a transition to “information warfare” with unprecedented demands on data collection, processing and exploitation.’

Effective employment of an integrated and networked force, to gain decision superiority and enable manoeuvre despite any intent to deny the same, was the hallmark of a fifth-generation force.

‘Such a change demands ingenuity, requiring a workforce that is empowered to think and act outside of the traditional norm. Innovation is essential to the realisation of the full potential of this investment. Our next generation of airmen must develop professional mastery that extends beyond mission specialisations. It must promote critical thinking, strategic understanding, innovative problem solving, collaboration and leadership—this is not business as usual,’ Air Marshal Davies said.

‘Airpower begins and ends with people and teams. A technical network alone is nothing.’

Air Marshal Davies said Australia was not ‘destined’ for war, but that the complexity of the environment and severity of the possible consequences meant it couldn’t be complacent:

I don’t know what the next conflict will be, but I do know that many of the tools of trade are now more freely available to potential adversaries than ever before. In future conflicts we can expect bases and support infrastructures, including civilian infrastructure, to be targeted through the use of physical and non-physical effects. These are no longer sanctuaries immune from attack.

The role of the ADF, to protect Australia and its interests, remains as relevant as ever in this dynamic and disruptive world. For the air force this equates to the delivery of the seven airpower roles—control of the air, strike, air mobility, ISR, C2, force protection, force generation and sustainment. We have seen that air power can strike deep; integrated with the joint force, it can generate decisive effect.

Today, air power provides support to troops on the ground, and critical visibility for commanders. Analytic, situational awareness and communications capabilities increasingly provide the full range of air power support to our joint and coalition engagement.

‘We need it to do more. Our air force is already capable. But it is now facing the greatest evolution of airpower in its history,’ he said. Success in the future battlespace requires the coordination of joint effects across all domains—a system of systems.

‘Airpower must be comprehensively integrated across the joint force to contribute meaningfully to the future fight.’

Back in March, the Minister for Defence announced the results of a study of JSF-related exports by PwC. She said that the ‘Joint Strike Fighter program will create 2,600 extra defence industry jobs by 2023, more than doubling the current associated workforce of 2,400.’ Given that total export contracts with Australian firms under the F-35 program amount to only around $910 million over 11 years, they’re encouraging numbers.

In comparison, we’ve been told that the $50 billion Future Submarine project will produce around 2,800 direct and supply chain jobs, and the $35 billion Future Frigate program will produce around 2,000 direct jobs. It’s little wonder that the Prime Minister, Treasurer and Defence Industry Minister have since joined the chorus singing the praises of JSF-related exports.

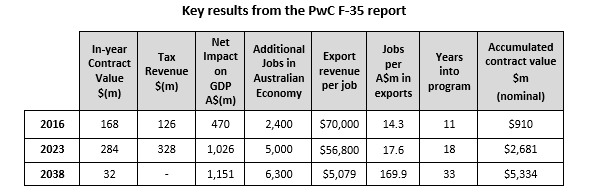

The PwC report highlights the results for 2016, 2023 and 2038 (see the table below). All US dollar contract figures have been converted to Australian dollars assuming 1AUD = 0.75USD.

The PwC report provides detailed results which can be averaged over the duration of the program. It predicts more than 24 jobs for every $1 million of JSF-related exports across the program’s 33 years. That corresponds to average export revenue of just over $41k per job. To put that in context, a survey of recently announced job figures for a range of defence projects (see the forthcoming ASPI Budget Brief) reflects expenditure per job created of $400k–500k, which is ball-park commensurate with the roughly $440k revenue per employee in the Australian manufacturing sector.

Clearly an explanation is called for.

The first difference between the government’s other announcements and the analysis by PwC is that the former are desk-top estimates of mostly direct jobs, whereas the latter employs what’s called a Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) model. So it’s not an apples-to-apples comparison.

I don’t pretend to understand the technical aspects of GCE modelling, but here’s what I know. Rather than just looking at direct and supply chain jobs, a GCE estimates the impact across the Australian economy. In so doing, CGE models take account of (1) the reallocation of resources and flow-on activities within the economy, and (2) the additional economic activity resulting from labour income.

If all we had was the PwC report, we might conclude that the higher rate of job creation simply reflects better modelling. We might even extrapolate and conclude that the government is underselling the economic benefits of its ‘buy Australian’ defence industry policy. But we have another data point.

As it happens, Defence produced an economic impact analysis of building submarines in Australia in 2015, also using a GCE model, which was released under FOI. It’s based on spending $15.1 billion over 16 years to build six Collins-like submarines. It found that the Australian economy would be $65 million per annum larger for the 16 years of the project, and predicted an additional 733 jobs would be created for the duration of the project. That’s despite assuming 1,000 direct and 1,900 indirect jobs.

To be clear, the submarine study says that of the 2,900 assumed to be working on the project, 2,200 of those people would have found work in other industries that were ‘crowded out’ by the decision to build locally. With a net employment forecast far below the government’s figures for the future submarine project, it’s easy to see why it was only released under FOI.

The modest net job creation predicted from submarine building deepens the contrast with the F-35 exports study. Averaging over each program, the submarine study predicts 733 net additional jobs from average annual expenditure of $938 million, while the F-35 study predicts and average of 3,939 jobs from average annual exports of only $162 million. Taken together, the two studies imply that every dollar of defence exports generates 32 times more jobs than a dollar spent building defence equipment in-country.

Even though both studies use a GCE model, there’s a significant difference between the two situations. While the submarine project requires additional taxation to fund the build, JSF-related exports don’t. Because CGE models take account of taxation, that may help explain the very different results. Indeed, all other things equal, additional taxation will subtract from economic activity. Other factors that might be relevant are the differing geographic locations of the two programs—SA versus mainly VIC and NSW—and differences in the calibration and implementation of the GCE models.

Taken at face value, a renewed emphasis on defence export facilitation and global supply chain agreements is called for. In some circumstances, the maximum economic benefit might be gained by foregoing domestic production in favour of securing access for local firms into global supply chains. Remember, the F-35 exports only came about because we’re purchasing the aircraft from US factories. If we’re going to use defence spending to grow the economy, let’s get the most out of it.

Of course, two isolated studies are a fragile basis on which to build a policy. Without further work, we can’t be sure how much of the difference between the two studies comes from the export nature of the F-35 program, as opposed to other differences in what was modelled, and how the modelling was conducted. Indeed, without independent replication, we can’t be sure that either study is correct.

As a priority, the government should commission CGE modelling to properly and systematically determine how Australian defence spending can best be harnessed to create jobs and grow the economy—including through both exports via global supply chains and local production. A good first step would be to have a third-party replicate the 2015 submarine and 2016 F-35 economic impact studies on a common CGE platform. Only then might we be able to properly understand what’s behind the dramatically different results.

Andrew Davies’ graph of the week about the elderly USAF tactical fighter fleet raises several issues. But before that it is worthwhile looking at the big US Defense budget picture below. The two big peaks are the Reagan defence build-up and Global War on Terror (GWOT) 2001–2014. Most of the current USAF fighter fleet was acquired in the Reagan years leading to, as Andrew noted, a fleet that is steadily aging.

The graph suggests that it’s unlikely that the USAF will again build a Reagan-era size fighter force. Reagan cut taxes and increased spending. This led to bigger deficits, which in turn led to raising taxes and cutting spending in the elder Bush’s presidency and the Clinton years. This worked, the US Federal budget went into surplus. But today, with the ‘fiscal cliff’ looming, it seems that the US is once again moving towards raising taxes and cutting spending. As the graph indicates, the Obama administration plans to constrain defence spending over the next five years. US defense spending will still be roughly half the world total, but a big Reaganesque increase looks unlikely.

There’s no joy for the USAF in all this and the USAF fighter fleet will just continue to shrink and grow old. There are those who think that the size of the Cold War fleet is still appropriate. But most wars since the Berlin War fell (excepting the 1991 Desert Storm campaign) have used relatively few USAF fighters, as vital to mission success as they were. The Precision Guided Munition (PGM) revolution now means that fewer aircraft can do the work of the larger iron bomb fighter fleets of the Reagan era. Read more

This week’s graph is a case of a picture that is worth $200 billion. Produced by the US Congressional Budget Office (CBO) in 2009, it shows the number of tactical aircraft procured by the US Air Force (USAF) every year since 1975, and the average age of aircraft in the inventory.

From 1978 to 1991, when production of the F-15 and F-16 ‘teen series’ strike fighters and the A-10 attack aircraft were in full swing, the annual buy averaged well over 100 aircraft. In terms of maintenance of overall fleet size and modernity, that was about ‘break even’. As the graph shows (click to enlarge), the average age of aircraft in the fleet hovered around 11 years throughout that period.

But from 1992 onwards, as production of the 1970s designs ramped down, the average age of the fleet began a steady upwards climb, reaching 20 years a few years ago. The delivery of 187 F-22s between 2002 and 2009 had essentially no impact on that trend. (Incidentally, the RAAF’s 71 1980s vintage Hornets and 24 brand new Super Hornets produce about the same average age).

Source: Congressional Budget Office Alternatives for Modernizing U.S. Fighter Forces (PDF), May 2009. Read more