Australia needs more defence grunt in its Pacific policy

When it comes to Australia’s policy in the Pacific islands, what’s first needed is a changed mindset. We need to recognise that the region is key terrain. It’s essential for US and Australian defence; it’s not a secondary theatre where we do ‘just enough to keep the locals calm and on side’. What we do in the Pacific islands region will tie directly to success or failure in a war with China over Taiwan.

Consider the challenges posed by a Chinese presence (military and otherwise) in the Pacific islands, even in peacetime. For Australia, it’d be tough to try to fight our way up towards Taiwan without getting whittled down in the process. The same goes for the US having to fight its way across the central Pacific.

The second key point is that our approach should be one of no ‘cargo cults’. We should look at the totality of what the US and Australia (and our partners) are doing in the region. If it looks like a cargo cult—showing up, putting on a good show and then leaving—then we’re doing things wrong.

It should be a permanent presence and should leave no part of the region untended. If you’re not there, you’re not interested. It doesn’t matter how handsome a party you put on when you pitch up. We should look at things from the locals’ perspective, not from a ‘theatre engagement matrix’ perspective where being busy is the main thing.

The third point to bear in mind is that money spent in the Pacific islands is like a maintenance fee or insurance. It is far cheaper than having to fight a war to recover them.

It’s also useful to consider the World War II analogy: China is interested in the Pacific islands for the same reason Japan was interested in them. It’s all about complicating US access to the Western Pacific.

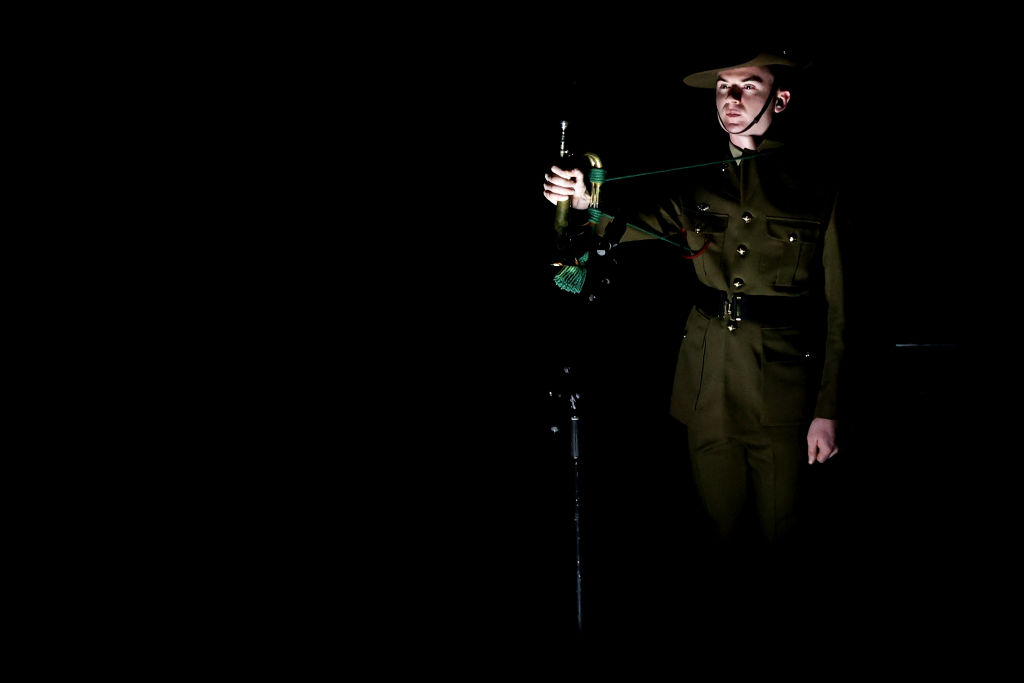

From an Australian military perspective, it’s not about bases but rather ‘rotational access’, which we should now deepen and broaden, along with the US. Australia should create a Pacific regiment. The focus should be on building island capacity in areas like disaster mitigation and response. The regiment could be headquartered in Fiji or Papua New Guinea with Australian Defence Force personnel integrated into it under a South Pacific command. We should find some junior officers who want to contribute to regional resilience in areas such as small unit tactics, surveillance and boat operations.

Working with locals, this would develop skills for local youth along with discipline that pays off later in life and feeds directly into local societies. It would seem to be a natural activity for the US Marine Corps’ new littoral combat regiments, offering valuable experience while influencing and facilitating US access. Australia should encourage the US to consider opportunities for bringing us and Japan into the effort.

We should set up national guard programs in certain island nations with US and Australian defence support. Disaster response can be the main focus. One or two such relationships should be with a combined national guard and Australian Army reserve unit. And maybe in a few cases we could designate a reserve unit to a Pacific island as well. The Australian government has promised to establish a defence training school in the Pacific. Along with the host nation, we should make it a joint effort of the US, Australia and Japan and make it a priority.

Australia should encourage the US to establish a marine expeditionary unit or amphibious ready group operating out of Darwin and elsewhere in northern Australia. It would be multinational. But with US, Australia and Japan as the core. This means that the Australian government needs to end the lease of the Port of Darwin to a Chinese company. The lease is preventing the rapid development of the port for more important security purposes and is slowing and complicating greater US Marine Corps and ADF use of the port.

Enabling greater US access to expanded facilities here in Australia is about our security and improving our defence facilities for our own use and for the use of our allies and partners. If Washington can capitalise on Palau’s offer for the US to establish a base there, then Australia should offer some military assets there. We’re now building 12 offshore patrol vessels. There could be a rotational access of, say, four OPVs through the area.

US and Australian defence forces should deliver health assistance to the islands. The Mercy, a 1,000-bed US Navy hospital ship, has sailed throughout the Pacific offering medical care to many island populations. Australia now has a Pacific support vessel that will expand the range of support we provide across the region, including delivering medical assistance. Australia should also work with the US to develop regular rotations of teams of military clinicians through host-nation hospitals for around four weeks each to leave a more lasting impact by developing a cadre of local health experts.

Australia, working with support from the US, should initiate a joint Australia–PNG project to enhance the port facilities and airfield at Milne Bay. It offers better potential defensive coverage of the vital Solomon and Coral Seas than Manus Island more than 900 kilometres to the north. Australian forces could operate from Milne Bay in support of PNG and other Pacific Islands Forum partners.

South Pacific defence ministers last year agreed to a Pacific-led initiative to develop a regional humanitarian and disaster response framework to refine the way countries in the region work together when disaster strikes. Why not take this to the next level with Australia and the US working with the islands to create a regional stabilisation and disaster response force?

Finally, Australia should be recruiting Pacific islanders into the ADF. Pacific recruitment sits comfortably with the goal of security and economic integration with Australia over time and at a pace and scale that’s welcomed by Pacific island countries. Military service is a unique offer we can make that China can’t and won’t. No changes to defence legislation would be required, only a change of policy.

Australia and the US must respond to both development challenges and geostrategic competition in the Pacific islands region. We can’t afford the luxury of choosing. And the military forces of the US and Australia have a vital contribution to make.