Editors’ picks for 2024: ‘The beauty of an 80 percent solution: lessons from the RQ-7B program’

Originally published on 26 July 2024.

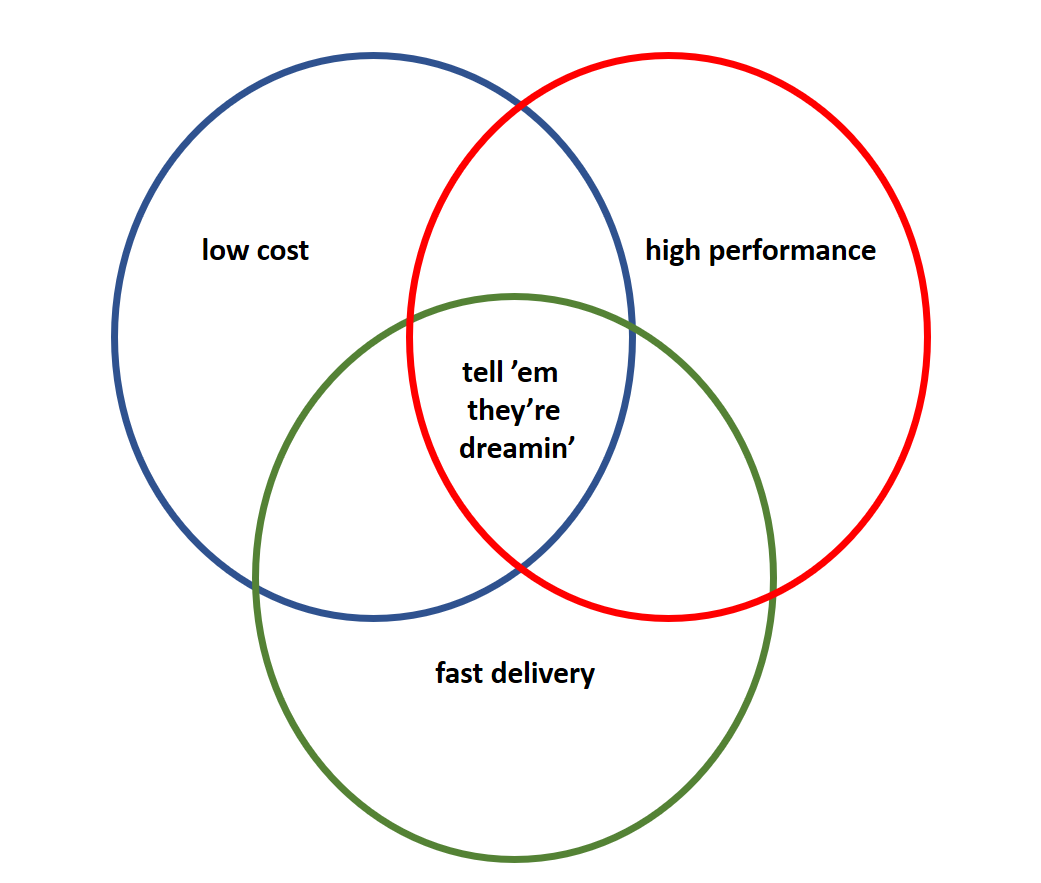

As so often, the Australian Defence Force wanted the exquisite solution. It wanted uncrewed battlefield reconnaissance aircraft of a design that wasn’t operational anywhere and would achieve performance that other countries didn’t have.

And the acquisition led nowhere—except to prompt a successful replacement effort that gave the ADF a powerful lesson in the merits of toning down requirements to get something that is good enough and can go into service fast enough.

The lesson has been formalised. Defence now defines the two key concepts in its Capability Lifecycle Manual. They boil down to this: identify a ‘minimum viable capability’ (MVC), which is a lowest acceptable military effect that meets the requirement, then get a ‘minimum viable product’ (MVP), something that will deliver that capability on time.

The 2023 Defence Strategic Review told the ADF to go for MVC and MVP.

MVP is widely known in business, but not in Defence. At a 2023 ASPI conference, several senior speakers couldn’t clearly describe it or give an example when asked.

Well, that uncrewed aircraft project offers a fine example.

It was Joint Project 129 Phase 2 (JP129-2), a long and unnecessarily complex process of providing aircraft for intelligence-gathering, reconnaissance and target identification for the Australian Army.

The story of acquiring an uncrewed aerial reconnaissance capability for the army ultimately involved three aircraft types and their associated ground systems: first the overly ambitious original design that Defence had to abandon; then the Boeing Institu MQ-27A ScanEagle that was leased as a gap-filler; and finally RQ-7B Shadow 200 from AAI Corporation of the United States.

The original design was still at the prototype stage in 2005 when Defence chose it and was authorised to proceed to acquisition. So that design had not in fact been finalised and could still have had plenty of problems.

And the ADF wanted the design certified to an airworthiness standard that no uncrewed aircraft anywhere had achieved. Furthermore, the aircraft were to operate at such long ranges that their radio communications would work at the extremes of physics. The communications would also have encryption cyber security not yet in use in any other Australian tactical systems. And all this was to be fully integrated into Australian Army vehicles supplying power, the other end of the radio link and command and control.

Over three years of contract negotiation the aircraft grew 50 percent in weight, the project needed release of contingency funds as costs rose, and there were signs of insurmountable technical difficulties.

Meanwhile, the ADF could not wait. It was on operations in Afghanistan and Iraq and in 2006 leased ScanEagles as an interim solution; they remained in use until 2013.

In 2008 the capability management team for JP129-2 recommended a reset to the Chief of the Army. It proposed:

—Terminating the contract for the original design;

—Defining an MVC as an approximately 80 percent solution to the specification;

—Choosing a US design that the US Army was already using and was available through the US Foreign Military Sales process—specifically, the Shadow 200; and

—Doing it all fast.

Toning down the requirement meant dropping nice-to-haves, as distinct from must-haves: the aircraft wouldn’t have to operate from amphibious ships, and the army would do without the unique airworthiness requirements. Ironically, the RQ-7B was an updated version of a design that had been rejected in 2005 for the project because of supposed capability shortfalls.

Over the next two years the equipment was acquired, the US Army trained Australian soldiers to use it at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, it was rapidly proven in tests at Woomera, and the first of the two systems was sent straight from Woomera to Afghanistan. Each system comprised the ground station and five aircraft; eight more aircraft were bought as spares.

Shadow 200s sent to Afghanistan were in a bare-MVP configuration and adapted to operate from shelters instead of US Army HMMWV trucks. What the Australian Army got at first was in fact only a 70 percent solution. But it worked, and it worked well.

Over the next few years it was progressively improved. It was adapted for mounting on the army’s own battlefield trucks, Unimogs, given ADF combat-net radios, tested and certified to Australian weapons targeting and engagement requirements, and made compliant with Australian work-safety standards.

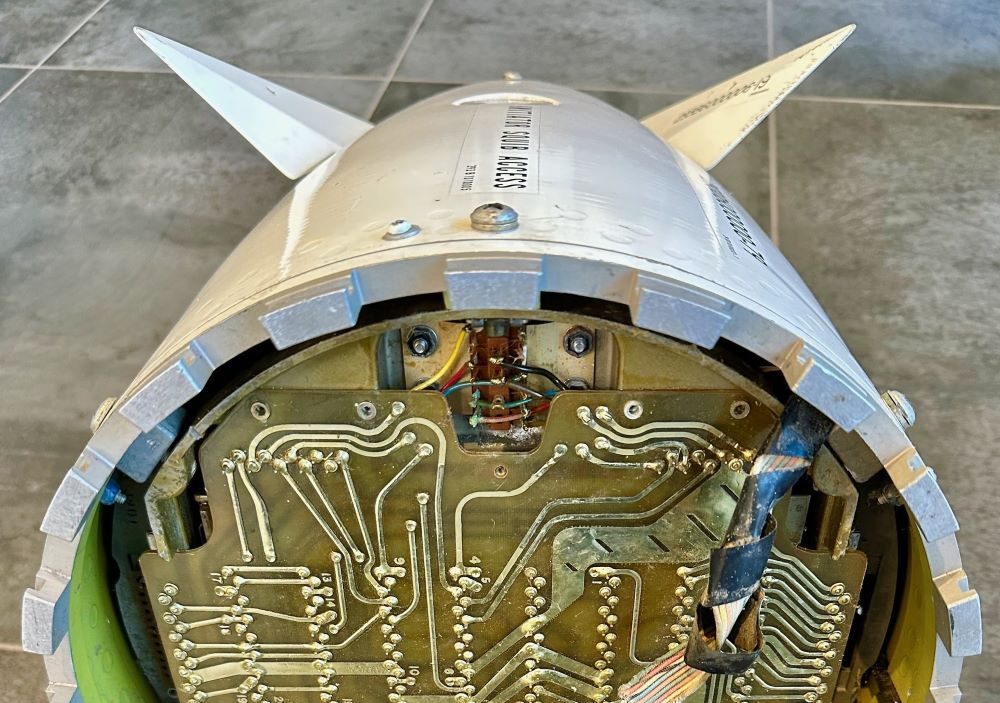

It was also given systems as bolt-ons, meaning they weren’t tightly (and expensively) integrated into it. One was for interpreting and sharing pictures from the aircraft; the others were a flight data recorder and a cockpit voice recorder on the ground operating station, both needed to meet aviation safety requirements.

All this was done in Australia by local businesses. By 2016, when the system was declared to have reached final operating capability, the Shadow 200s had achieved the intended 80 percent MVC configuration—and had been acquired for only half of the budget that Defence had expected to spend before changing horses in 2008.

The lesson is that Defence can greatly improve acquisition efficiency if a capability manager first agrees with operators what the 100 percent solution looks like, then approves going ahead with an MVC of 70 to 90 percent.

As with the Shadow 200s, a program can first deliver an initial operational capability at the 70 percent level then progressively advance to 90 percent. Declaring a final operational capability isn’t necessary, because it’s recognised that 100 percent will never be achieved. This model is particularly suitable for areas in which technology is advancing faster than the pace of Defence acquisition.

It involves a preference for mature, off-the-shelf, in-production equipment and teaming with a supplier that has an industry presence in Australia.

The need for speed must loom over the whole process, and it’s essential to try to come in under budget. With current constraints in the capability acquisition program, every dollar saved on one project is needed for another.

In

In