Good enough to win: rethinking risk in innovation

Innovation policy is often built around optimism. But in a world of live contest across the economy, the environment and the broader geostrategic landscape, progress cannot afford to wait for perfection.

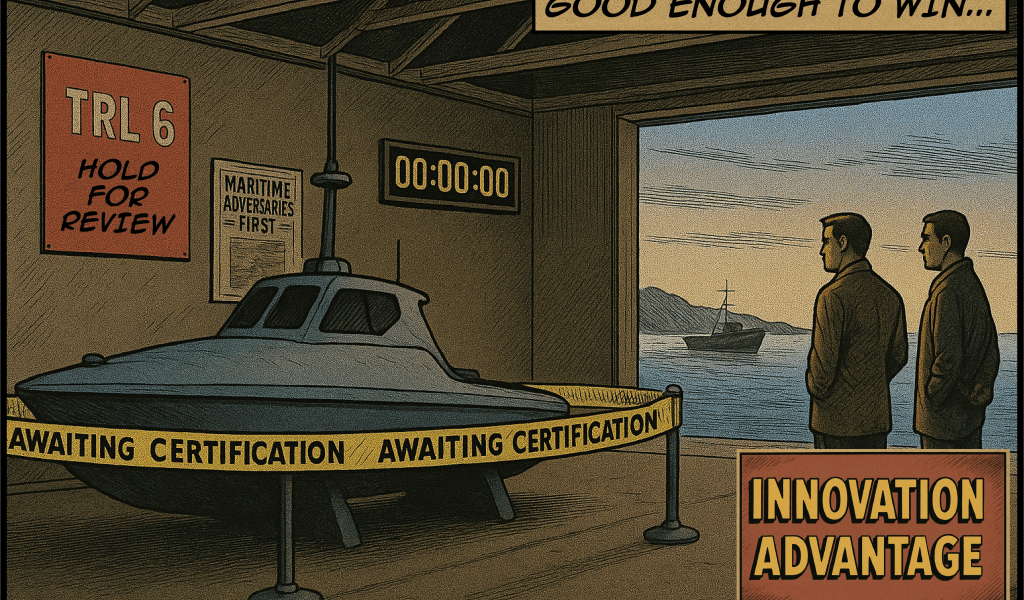

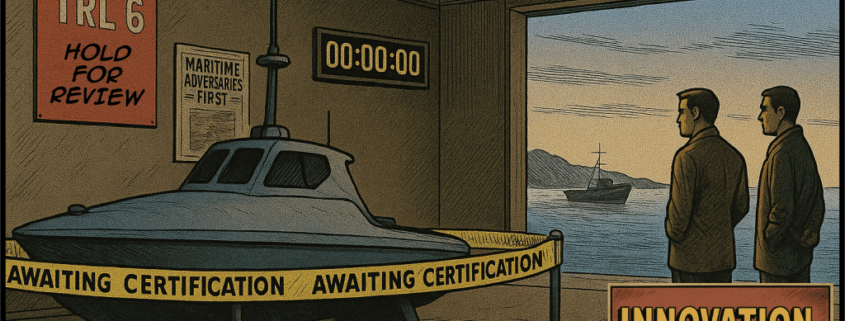

The scale of technology readiness level (TRL)was designed to assess the maturity of spacecraft systems. Today, it is embedded across governments and industry, especially in defence. Developed by NASA in the 1970s, it assesses the readiness of technologies in development on a scale from one to nine, with TRL 9 technologies being ‘proven and ready for full commercial deployment’. Originally intended as a diagnostic, TRL has become a gatekeeper. The result is a system where technologies with promise are paused for perfection, even when conditions demand speed and adaptability.

Projects are shelved awaiting maturity, overengineered to meet idealised requirements, or overtaken by those willing to iterate—essentially, learn from mistakes—in the real world. As Admiral Samuel Paparo, commander of the US Indo-Pacific Command, told the Honolulu Defence Forum in February: ‘We can’t let better be the enemy of good enough. We have to act now.’ That urgency applies to the entire innovation system.

Innovation is no longer just about economic growth. It underwrites national safety, resilience and strategic autonomy. Our ability to respond to crises, deter coercion and build trusted systems depends on our capacity to deploy at pace.

That requires a shift from ‘mature and proven’ to ‘deployable and adaptable.’ TRL 5 or 6 technologies, already validated in relevant environments, are often ready enough. In the commercial sector, this is the moment where products ship, feedback loops tighten and iteration begins. In Australia, it is often where momentum dies. Public agencies hesitate, procurement stalls and the ecosystem receives no signal. The result is lost time and lost learning—missed opportunities to gather operational insight, improve design and build trust through use.

The fixation on maturity carries real costs: capability acquisition slows; risk piles up downstream; and uniformity, often treated as a virtue, becomes a vulnerability. The system also defaults to large-scale production runs over small-batch deployment, sidelining options for controlled rollout, rapid feedback and iterative refinement. Whether you are a university research team, a multinational prime or an early-stage firm, the pattern repeats. Momentum stalls, talent exits and impact slips away.

Sometimes even ‘proven’ is not enough. Technologies that clear trials are often subjected to years of additional validation because the system lacks flexible paths to deployment. This is inertia, not caution. And in an environment shaped by time, trust and tempo, it can be fatal.

Meanwhile, others are learning through contact. Commercial rivals, state-backed actors and high-agency founders are testing, failing, refining and redeploying. Not all of it works, but what does, improves fast. If we are not learning at the same rate, we are falling behind.

Across the private sector, iteration is a norm. Startups ship early and often, not because they are more brilliant or better funded, but because delay means irrelevance. That same imperative should apply to public-interest innovation in defence, disaster response, supply chain security or climate adaptation. The system falters when paperwork outweighs performance or when procurement timelines exceed product lifecycles.

Australia has made progress. The Advanced Strategic Capabilities Accelerator (ASCA) was created to drive independent capability, and the National Reconstruction Fund is starting to shape more deliberate capital flows. But the gap between prototype and deployment remains wide. ASCA in particular is still maturing and remains opaque to many who engage with it. Acceleration requires clarity about pathways, timelines and thresholds for engagement. Without that, we’ll miss the opportunity to turn ASCA into a genuine national instrument linking research, procurement and early adoption. Until other agencies beyond the Department of Defence are empowered to adopt a similar model, whole-of-government innovation will remain fragmented.

We need a deliberate shift. That means putting real money behind fieldable capability, embracing limited release as a form of validation, and treating users—whether in uniform, on the factory floor or in frontline public services—as part of the development loop.

It also means redefining risk. Strategic risk is not the same as technical risk. Waiting for certainty may feel prudent, but if it means missing the moment, the consequences are far greater. Public institutions must be empowered to act before the finish line is crossed, because that finish line keeps moving.

Innovation does not fail because of a lack of ideas or ambition. It fails because of system choices: what is funded, who is trusted, and how long we are willing to wait. Raising the tempo does not mean lowering standards; it means confronting the fact that, in today’s strategic environment, delay is its own form of risk.

If we want to move faster, we also need to lead smarter. That means clarifying who owns the mission, who shapes the market and who connects capability to consequence. Because if speed is now strategic, then authority—real, coordinated and operationally grounded—must be as well.