Economic security and geostrategic competition: fostering resilience and innovation

Australia and other democracies have once again turned to China to solve their economic problems, while the reliability of the United States as an alliance partner is, erroneously, being called into question.

We risk forgetting lessons of the past when we cling to the long-gone notion of the free market, which Beijing sees as democracies opening themselves to China’s unfair business practices. Economics and security are closely linked: we must build resilience and foster innovation to prevent economic dependencies that weaken our security.

We should be concerned when countries impose tariffs on friendly countries, as the US is doing. It erodes trust, weakens solidarity among like-minded democracies and dangerously risks a tit-for-tat approach of revenge tariffs that will leave us all poorer. This drives inflation while passing costs onto consumers.

But while we need to keep working for a different outcome—as the Australian government is doing—we mustn’t focus on spot fires when the forest is ablaze.

Almost a decade ago, Australia led the world by abandoning an outdated foreign policy of balancing economics and security. We recognised that trade interdependencies didn’t deter conflict and that short-term financial interests should never outweigh security concerns. Balance sounded good in theory but in practice meant trade-offs that left us unsafe.

It was China’s actions that forced the change: having become our largest trading partner, Beijing used our economic reliance as leverage to implement a systemic program of security breaches and threats against us, from cyber intrusions to foreign interference.

Unfortunately, recent trends reveal that security trade-offs weren’t abandoned so much as temporarily paused. Many democracies are responding to immediate cost of living pressures and hoping security threats can be kicked down the road. This is a policy of security crisis delay, not deterrence.

Economic prosperity is needed to pay for security, and security without prosperity leaves us vulnerable to decay. But as is the case for individuals and households alike, assurance comes at a cost. So, the key question that confronts is what is the short-term price—an insurance premium of sorts—that we are willing to pay for long-term confidence of our prosperity and security?

Western countries need to look beyond resilience and risk reduction to embrace a more comprehensive strategy—one equally focused on (shared) innovation and competitiveness, especially in those emerging technologies that will determine future prosperity and security.

Brad Glosserman correctly argues that, in response, the US and its allies have been ‘doing economic security wrong’ by focusing almost exclusively on resilience and risk reduction. This has meant overlooking deterrence, and not prioritising future competitiveness. Partners and allies must define key industries and sectors, and stop choosing cheapest associated supply chain.

They must strengthen resilience by establishing frameworks to protect critical and emerging technologies from intellectual property theft and economic coercion by China. And, as Raquel Garbers argues, enhanced deterrence requires education on what economic warfare is and how it works, and with tools that disincentivise economic activities with hostile states.

Glosserman correctly emphasises the importance of supporting innovation and ‘unlocking innovative potential’. Resilience requires us to move beyond traditional notions of just protecting the economy to an approach that prioritises innovation and technological leadership.

To establish an effective strategy, we must understand what specific policies governments can implement to foster a innovation in critical and emerging technologies. This also requires increased collaboration between the US and its allies, particularly in areas where China has a strong lead.

We need to leverage the strengths of countries such as India, which ASPI’s Critical Technology Tracker has identified as an emerging centre of research excellence, to diversify research partnerships and build a more resilient global innovation network. We must also be wary of the short-term focus of shareholder capitalism and its negative impact on long-term economic security.

We should consider how can we rebalance the capitalist model to prioritise, incentivise and reward long-term investments in innovation and resilience. The prosperity and economic growth needed to best provide national security won’t result from protectionism, but from a long-term strategic approach to emerging technologies.

Doing so, however, will still require us to remember you get what you pay for. Any savings we gain from prioritising cheap supply chains in the present will ultimately be outweighed by higher security costs in the future.

We need to remember that short-term disagreements with friends will pass as they have before. National interests may on occasion come into sharp contest, but strategic alignment will persist. It is systemic and malign challenges that require our collective focus and investment.

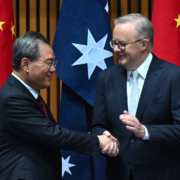

China's Premier Li Qiang (L) and Australia's Prime Minister Anthony Albanese shake hands during a signing ceremony at Parliament House in Canberra on June 17, 2024. (Photo by LUKAS COCH / POOL / AFP) (Photo by LUKAS COCH/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

China's Premier Li Qiang (L) and Australia's Prime Minister Anthony Albanese shake hands during a signing ceremony at Parliament House in Canberra on June 17, 2024. (Photo by LUKAS COCH / POOL / AFP) (Photo by LUKAS COCH/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)