Capital gaps and complacency: investment imbalance undermines sovereignty

Australia’s ability to generate breakthrough ideas has never been in doubt. But despite increasing recognition of the need for national resilience, the country still lacks a capital system built to serve strategic purpose.

The failure to translate innovation into deployable capability is not just about procurement models or research policy; it is also about capital. Specifically, the absence of a coherent financial architecture designed to support dual-use and high-consequence technologies from early development through to scaled delivery. Innovation policy without investment infrastructure is just aspiration.

Today, Australia’s investment landscape is structurally misaligned with the needs of sovereign technology developers. Risk appetites are low. Procurement cycles are slow. Incentives reward familiarity rather than mission relevance. Venture capital remains skewed toward low-friction consumer software and resource plays. Government programs favour either basic research or late-stage commercialisation. The middle—where risk is highest and impact is greatest—remains a void.

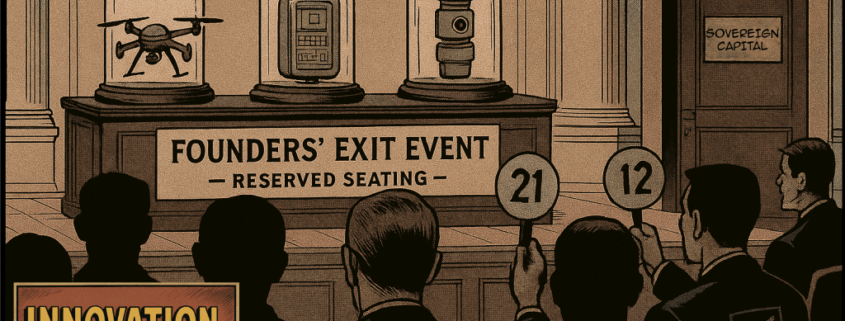

For firms operating at the intersection of research, security and systems integration, this gap is existential. They are often too early for procurement, too technical for mainstream venture, and too strategically sensitive for foreign capital. With limited options, many are forced to look offshore. When that happens, we don’t just lose ownership; we lose eligibility. Technologies developed here often become ineligible for deployment in the very systems they were intended to secure.

Australia’s foreign investment screening regime provides some guardrails. But by the time an acquisition is flagged, the upstream incentives that pushed a company to exit have already done their damage. The deeper issue is that we have not built a capital stack calibrated for sovereign needs. Without it, the innovation system will continue to select for technologies that are easy to fund, not those that are hard to replace.

This is more than an economic issue; it is a structural vulnerability. AUKUS Pillar Two assumes each partner can deliver capability at speed. But delivery depends on more than science. Without the financial capacity to scale quantum systems, autonomous platforms, cyber tools, or advanced undersea technology, Australia’s contribution will remain confined to research. We will participate in design conversations but not in delivery.

Other countries treat capital as a strategic lever, not just an economic input. The United States co-invests public dollars alongside mission-aligned venture funds to actively shape innovation markets. Britain’s National Security Strategic Investment Fund blends state and private capital to accelerate priority capabilities. Across Europe, governments are increasingly viewing strategic capital as an enabler of both competitiveness and resilience. NATO’s €1 billion Innovation Fund, backed by 24 member nations, is designed to invest in dual-use technologies for defence and security—pooled sovereign capital deployed for collective security effect.

Australia has nothing comparable. The National Reconstruction Fund and Advanced Strategic Capabilities Accelerator (ASCA) are progress, but they do not operate as instruments of capital power. Their mandates are limited. Their signals are fragmented. Neither is designed to de-risk foundational technologies that the market won’t touch, nor to crowd in private capital to areas with national consequence but low near-term return.

Instead, we rely on pilot grants, university incubators and disconnected accelerator programs—all useful, but insufficient. There is no institutional centre of gravity that aligns capital flows with strategic priorities. No mechanism to protect promising capability from early exit, or to finance the kind of long-horizon bets that national resilience demands. Without dedicated financial infrastructure, Australia will continue to underwrite research while outsourcing value creation, control and deployment.

This vacuum is made worse by cultural inertia. Governments and investors remain cautious toward security-relevant technologies, often viewing them as slow, complex, or difficult to scale. The result is a capital cycle that disincentivises innovation with long-term strategic value. We talk about sovereignty, but we fund convenience.

If Australia is serious about building sovereign capability, we need a deliberate investment posture. That means creating public-private instruments, mission-aligned venture funds, co-investment models between agencies and trusted capital, and procurement settings that reward performance and resilience—not just scale or price.

Most importantly, we must recognise that capability is not just something we develop. It is something we finance. Without a system that supports, retains and scales our most strategic technologies, we will remain dependent not just on foreign components but on foreign capital to build them.

The next phase of innovation reform must confront this directly. Capital is not neutral. It shapes what gets built and where. Until it is aligned with the national interest, we will continue to export the value of our ideas and import the technologies on which our sovereignty depends.