Taking Australian diplomacy digital

What’s the problem?

Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) now has a presence on the main digital platforms, but it is yet to master digital diplomacy: using these powerful new communication tools and platforms to better conduct its core mission of persuasion, influence and advocacy. There’s too much use of new media channels to transmit old media content, a tendency to duck rather than address difficult issues, and a failure to engage within the digital life cycle of a news story.

Data analytics and the integration of digital tools into mainstream diplomatic campaigns are both lacking. Beyond this, there’s a need to rethink how Australia does diplomacy in the digital age.

DFAT needs to find better ways to communicate with its stakeholders, using digital tools. It needs to recognise that increasingly statecraft is playing out in the cyber and information domains, and invest more in equipping itself to engage in those domains—even when such online engagement brings risk.

DFAT must also reconceive its overseas presence and embrace some of the agility and nimbleness of the tech world in doing so.

What’s the solution?

DFAT needs to start treating digital diplomacy as core tradecraft, rather than optional add-on. It should provide compulsory digital training for all outgoing heads of mission and encourage healthy internal competition and innovation. It should pilot more sophisticated data analytics tools and integrate digital tools into regular diplomatic campaigns. It should develop and pilot a new stream of diplomatic reporting that’s punchier and timelier, and reaches a broader audience on hand-held devices.

DFAT should create new positions of ambassador to Silicon Valley and ambassador to the Chinese tech giants based in Beijing. It should experiment more with ‘pop-up’ diplomatic posts, pilot one-person posts and encourage innovation and experimentation in the conduct of digital diplomacy, conceiving of embassies as hubs and connectors for a broad set of interactions.

Finally, DFAT needs to adopt some of the nimbleness and agility of the tech world in how it conducts Australia’s external policy. Failure to do so means the field is left to others.

Introduction

Australia’s DFAT has come a long way in a short time in its embrace of digital tools and technology.

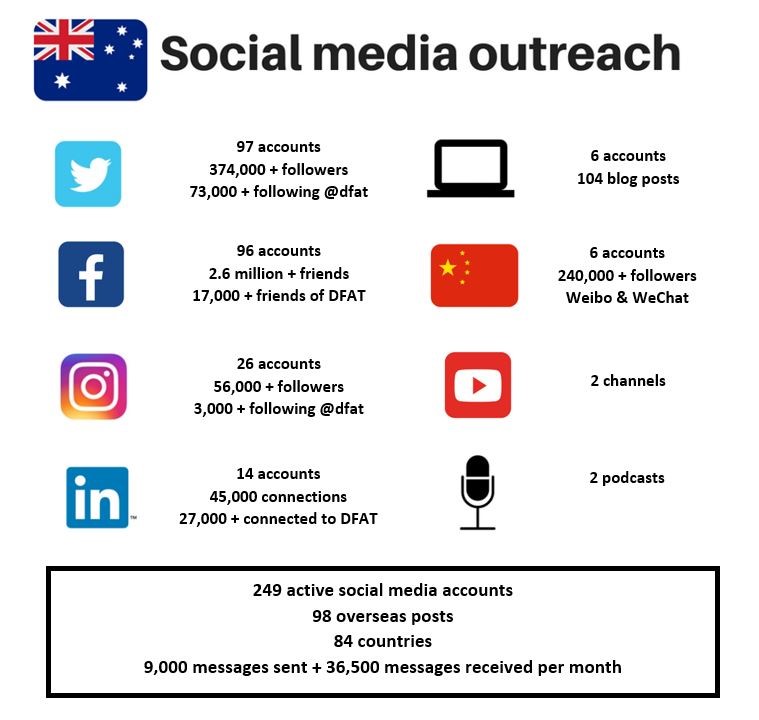

DFAT, and most of our embassies around the world, now have a significant social media presence, often across several platforms (Figure 1). There has been an explosion of Twitter feeds, Facebook pages, Instagram accounts, and even blogs and YouTube channels,1 adding colour to what was (and remains) a rather lifeless website-only presence. In this, DFAT has been helped by political leaders who have embraced these tools as a means of modern-day communication.

After coming late to the game,2 DFAT now has a decent digital presence when benchmarked against other foreign ministries worldwide. It’s certainly not in the top 10, but it is credible.3

Figure 1: DFAT’s social media presence

Digital, but not yet doing digital diplomacy

However, in the rush to embrace digital media, there’s a danger that some of the bigger questions have gone begging, and that ends have been confused with means. Doing digital diplomacy well not only requires having the requisite digital platforms—it entails using them strategically and effectively to advance a diplomatic agenda.

This is where DFAT is struggling: it has gone digital, but it isn’t yet doing digital diplomacy. Having a large number of social media accounts and a growing crop of followers or friends isn’t sufficient. The test of success is whether those factors are being properly utilised to bring Australian diplomacy from the analogue into the digital age.

A changed operating environment

The essence of diplomacy hasn’t changed. Its main purpose remains the facilitation of communication between states and the exertion of influence (on other states or the international system) to protect and advance national interests. But what has changed vastly, almost beyond recognition, is the operating environment of diplomacy.

Even as recently as a decade or two ago—well within the professional lifespan of most of Australia’s senior diplomats—diplomacy as a profession, and hence DFAT as an institution, enjoyed several natural monopolies. First, there was the monopoly on information. It wasn’t that long ago that diplomats would fax press clippings or transcribe news articles and send them back to their capitals.

At a time when news on developments within other countries was scarce, and almost impossible to access remotely, diplomats stationed abroad were a vital—sometimes the only—source of information for capitals hungry for such intelligence.

Second, there was the monopoly on communication. In the era before modern modes of communication, the bulk of interactions between states took place through the medium of their diplomats. Leaders would meet or talk occasionally, but usually the challenge of making direct contact meant most communication was, of necessity, passed through ambassadors or envoys.

Third, there was the monopoly on representation. When communication with capitals was slow and difficult, and it could take several weeks to get an answer, diplomats abroad were expected to make decisions and improvise within a wide area of policy discretion.

These natural monopolies guaranteed relevance for foreign ministries, DFAT included, and sheltered them from competition. A government simply couldn’t run a foreign policy without a foreign ministry and its overseas diplomatic missions. Modern-day technology, however, has eroded most of these natural monopolies.

Diplomats no longer enjoy a monopoly on information. Leaders and decision-makers in capitals can readily access and follow most news from abroad, usually on demand, and from a variety of sources. Nor do diplomats enjoy a monopoly on communication. Today, leaders and senior officials are just as likely to communicate directly with their counterparts in another country—by phone, email, text message or, increasingly, an encrypted chat service—rather than through their diplomats.4

Finally, the monopoly on representation has ended. Diplomats are now expected to check nearly everything of significance with their capitals first, and modern communications mean they can (and are expected to) obtain revised instructions on how to handle an issue almost instantaneously.

Disruption, disintermediation and the digital pivot

The end result is that diplomacy has become a much more competitive space. Diplomats are being disintermediated by new technology and communication advances. States are increasingly able to understand, communicate and negotiate directly with other states, without the need for the intermediating service of diplomats. With the disruption of much of the traditional role of diplomats, the challenge for foreign ministries today is to pivot: to find new ways to generate value and ensure relevance in a much more contested field. And this is where digital tools can prove so important.

One of the main purposes of national security agencies is to deliver a strategic effect: to shape the behaviour and decision-making of foreign countries and their leaderships. Defence forces do this through alliances and partnerships, their force posture, deployments, joint exercises and military diplomacy (and, in extremis, through the threat or use of force). Development agencies do it through the direction and composition of their aid spending. Intelligence agencies do it through the collection of sensitive information, espionage and disruption.

In diplomacy, words are the bullets. A strategic effect is delivered through persuasion, influence, argument and advocacy directed towards a foreign population, nation or group of key actors or decision-makers. For this task, new communication tools—and especially social media—are a potential boon for diplomats.5 They allow diplomats to engage directly with the public or segments of the public in their country of posting, often in a targeted fashion. They provide the tools to deliver a message or engage in debate directly, rather than through traditional platforms.6 And they allow real-time interaction with a rapidly evolving media cycle, including the ability to rebut falsehoods, contest narratives, correct mistakes and provide the public with additional context to media reporting.

This is especially important now that political power is highly dispersed (partly the result of digital media giving each person a loudspeaker). To be an effective diplomat today requires more than just the formal engagement of your host government. If you want to be effective and shape the course of decision-making, then you need to be monitoring and engaging with those who shape the decision-making environment of political leaders within a society. That might include the media, business and industry groups, civil society, pressure and lobby groups, religious organisations, politically active diasporas and social media ‘influencers’. While this may be less true in autocratic countries, even there—thanks to social media and digital platforms—civil society has a voice that it previously lacked, and a means with which it can be directly engaged.7 Knowing and understanding the terrain of local opinion, and how to engage and shape it—the ‘last three feet’ of diplomacy8—is the unique value proposition of today’s diplomat and something that only a local, informed and networked presence can provide.

A credible but flawed digital presence

DFAT and the Australian network of embassies and high commissions abroad now have, on the whole, a credible digital presence—the tools needed to conduct those last three feet of diplomacy. This is necessary but not sufficient. The challenge is to fully utilise these platforms to conduct DFAT’s core business, which is diplomacy. And here, there’s still quite some way to go. There’s not yet a wholesale recognition and appreciation of how the advocacy landscape has changed. As a result, and with a few stand-out exceptions, most of DFAT’s digital channels suffer from the same three ailments.

First, there’s too much use of new media channels to transmit old media content. Digital media are a different format; they speak to a different audience, and require different—and more engaging—content. Good digital content is pithy, impactful and tailored, but too little of DFAT’s digital content meets that test. Using new media channels to transmit old media content (press releases and the like) ruins both.

Second, there’s a pronounced tendency for DFAT’s digital platforms to duck the difficult issues. There’s a place for building brand Australia, promoting tourism and spruiking soft news stories about Australia on digital platforms, but public and cultural diplomacy can’t be the sum total of our digital effort, or else we risk being (in the words of one insightful commentator) ‘all gums, no teeth’.9 Tempting as it is, there’s no point in running dead or lying low when a controversial issue is unfolding. This is exactly when digital platforms come to the fore and the credibility of your digital presence is tested. Too often, when a storm of controversy is raging all around them, DFAT’s digital channels bury their heads in the sand, go radio-silent, or promulgate the Panglossian fiction that all is well. If Australian nationals are set to be executed in a foreign country, or there are suggestions that the Chinese are building a military base in the southwest Pacific, or if a candidate for the Philippines presidency jokes about the sexual assault and murder of an Australian missionary, then we should expect that the relevant Australian digital diplomatic platform will have something worthwhile to say about it— to articulate our views and interests on an important issue.10 Likewise for major world events. The message must obviously reflect diplomatic realities, but to say nothing in such scenarios is simply not credible. It also lacks a prized trait of the digital age—authenticity—and so diminishes the value of the platform and treats readers as fools.

Figure 2: Twitter feed from selected foreign ministries on 12 June 2018, date of the US – North Korea summit in Singapore

Closely linked to this is a frequent failure to respond within the digital life cycle of a news story. Time differences and clearances may make this challenging, but our senior diplomats abroad have enough judgement and common sense to be trusted—indeed encouraged—to speak publicly on most issues within their patch without having every word approved by Canberra.11

Third, there’s a lack of personality in much of DFAT’s digital content. Part of the appeal of social media is its authenticity and directness—the idea that you get to know the person behind the message and can interact with them directly. But most of DFAT’s digital media content attempts to uphold the traditional division between public and private spheres. It’s stiff and aloof, and frequently non-responsive to attempts to engage. That’s an approach that may remain suitable to traditional diplomatic settings, but it jars in the flat, non-hierarchical, informal world of digital.

Operating in a new information domain: opportunities and threats

If used as part of a comprehensive strategy, the new digital world provides many opportunities to reinforce traditional diplomacy. The UK used digital tools to complement traditional diplomacy in its successful assembly of a broad coalition to respond to Russia’s apparent use of chemical weapons on UK territory, in Salisbury (Figure 3). Canada deployed a multifaceted digital campaign to support its objectives as G7 chair (notably, its initiative to tackle the problem of ocean plastics). Russia is an adept practitioner, frequently taking to digital channels to muddy the waters, promote alternative theories and create distractions when under international pressure (Figure 4). These countries have each integrated digital platforms into the prosecution of mainstream diplomatic priorities and campaigns, realising that digital tools can have a potentiating effect in support of a diplomatic campaign. In Australia, we’re yet to do this properly: we maintain an unhelpful separation between the digital realm and the mainstream diplomatic realm.

Figure 3: Part of the UK’s digital diplomatic effort to hold Russia accountable for Salisbury

Figure 4: Twitter feed from the Russian Embassy in London

Professional data analytics can be a powerful tool for this new diplomacy. Big data and network analyses can help identify online influencers and force amplifiers; track how narratives spread among online publics, and thus help to shape or combat them; allow communications that are tailored to the preferences and attributes of specific online communities; and support the rollout of sophisticated, multiphase campaigns. Most major corporate outfits use such tools, as do the diplomatic services of many foreign countries. The UK Foreign Office even has an internal ‘Head of Data Science’ position.12

Australia needs to get similarly professional and move beyond the simple counting of ‘likes’ and ‘followers’ as the metrics of digital impact.

Just as digital tools bring new opportunities to diplomacy, so they also bring new threats. They are changing the nature of statecraft, and the information domain is growing in importance as a theatre for contest between states. ‘Control of the narrative’—about what happened, about who’s at fault, about where justice lies, about what’s ‘real’ and what’s ‘fake’—is at the heart of this contest (Figure 5).

Diplomats have an important role to play here, in combating misrepresentations, squashing rumours and misinformation, and promoting their own country’s analysis and policy. Effective digital tools and good data analytics will be vital to this effort.13

Figure 5: The information domain is becoming a new theatre of state competition: textbook ‘trolling’ by two of its most capable practitioners

Similarly, today’s digital age means that disinformation, propaganda and rumours designed to influence or destabilise another country’s political system can be launched almost instantaneously, from across the globe, timed for maximum impact, and targeted towards a narrow audience (Figure 6). Unlike overt steps or traditional covert action, such measures are low-cost, low-risk and highly deniable. Russian state interference in the 2016 US presidential elections is likely to be just the tip of this iceberg.14 Although defending against such attacks is primarily the work of intelligence and cybersecurity agencies, we should expect our diplomats to be alert to the risk of such attacks and attuned to the tell-tale fingerprints. But they need to have the tools and the digital literacy to recognise, understand and engage with such information-warfare and ‘active measures’ campaigns.

Figure 6: Content identified by Twitter as originating from and spread by the Russian Internet Research Agency during the 2016 US presidential election.

Source: Update on Twitter’s review of the 2016 US election, 31 January 2018, Twitter, online.

Moving beyond social media

DFAT’s use of digital tools needs to extend far beyond social media, however. In the consular sphere, the department now does a good job in engaging with the travelling public through the digital Smartraveller platforms, but it is yet to modernise how it communicates with some of its main clients within the government.

The Australian diplomatic network’s main form of communication remains the classified diplomatic cable or telegram. This was once one of the best—indeed one of the only—ways of communicating information and analysis from abroad in a timely and secure fashion. But while modern technology has since moved on, and the pace of events with it, the cable system has remained frozen in time. For the demands of the modern ship of state, it’s too slow, too cumbersome and too difficult to access to be of much operational use. It’s thoroughly analogue, is largely internally focused and has a steadily shrinking readership and impact.

DFAT’s continued reliance on this system as its primary means of communication needlessly restricts its audience and increasingly deals it out of policy influence in Canberra, where many of the national security agencies don’t access or don’t bother to read DFAT’s cables. The department is completely out of sync with the working habits and preferences of today’s governing class, and how they wish to receive information. It doesn’t connect easily or widely to other agencies. Consequently, DFAT’s analysis and advice from its overseas network—one of its main value propositions—is underutilised and undervalued, with implications for policy influence, credibility and the contest for finite government resources.

DFAT must create and foster new methods of communication that are timelier, more accessible and more relevant. There should be different information products for different purposes and different audiences, and the cable system should be only one of several ways in which our diplomats convey information and analysis. As just one suggestion, why not create the equivalent of an encrypted Telegram group or closed Twitter feed that allows non-sensitive but time-critical reporting from across the diplomatic network, with a smattering of judgement and analysis, to be accessed by decision-makers in news-feed style from their handheld devices? Figure 7 shows what it could look like: daily headline take-outs from across our diplomatic network, designed for decision-makers without the time, ability or appetite to wade through the cable system (but with links to more comprehensive analysis). There would still be a place for more detailed reporting and analysis (perhaps accessed via links to a secure cloud-based site), but that, too, should be in a form that reflects the habits and preferences of the readership. Newspapers have made the painful transition away from print and towards new media. DFAT should walk the same path.

Figure 7: Illustrative example of a sample DiploFeed from 2018 (fictional infographic only—does not represent the views of DFAT or its posts)

Rethinking diplomacy

We need to rethink how we do diplomacy in the digital age. A diplomatic presence shouldn’t always have to mean an embassy or a chancery, with all the expense and infrastructure and security overlay that entails. Modern-day communication tools are so powerful that we should rightly expect our diplomats to operate more self-sufficiently, just as foreign correspondents do. There are many parts of the world where Australia would benefit from greater diplomatic representation—we have one of the smallest diplomatic footprints of any country in the OECD, after all 15 —but where we have none because the entry costs to establish a full embassy are so high. Digital tools have brought those barriers to entry down. There should no longer be a minimum viable size for an embassy. We should consider an ‘embassy-lite’ or one-person post in countries where we could do with a presence but can’t justify a fully fledged embassy. With DFAT’s ‘pop-up embassy’ in Estonia, Australia has made a small start down this path. We should continue.16

Similarly, we must assess whether states and international organisations are the only external actors that are worthy of a dedicated diplomatic presence. We should look at creating dedicated ambassadors to the tech giants of Silicon Valley, as France and Denmark have done.17 The FAANGs— Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Google—are now immensely important international actors in their own right. Together, their market capitalisation is US$3 trillion, but it’s their business model and ubiquity as much as their size that make them key actors for states. We have issues at stake with each of them—from privacy to taxation, from counterterrorism to cyber-interference and national security capabilities. Similarly for the major Chinese tech giants, the BATs (Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent), whose enduring influence might prove to be greater and about which we know and understand far too little.

Why not have ambassadors dedicated to building and managing these critical relationships, which are surely as important as our relationships with some of the smaller countries where we maintain a diplomatic presence?

In order to modernise diplomacy, Australia needs to begin envisaging the diplomatic network in a different way. Whereas in the past the government provided the network and infrastructure for traditional diplomatic interactions, the erosion of that monopoly means this network is at risk of becoming an underutilised asset. The flag and the chancery, the titles and the flummery, still count for a lot, as do the local networks, contacts and expertise, but how do we get more out of those assets?

The answer lies in broadening our conception of an embassy. We should be using our overseas presence as a platform and enabler to advance our interests across a much broader spectrum, and for a much broader set of stakeholders. Trade, economic and commercial diplomacy have always been traditional partners in this respect, but we need to look much further afield. How can we use the overseas network to support collaboration in innovation and research? How can we use our embassies to keep Australia on the cutting edge of public policy? What value or perspectives from overseas can be brought to bear on some of the major challenges in Australian domestic policy? These areas will depend on the complementarities and opportunities that exist, but they shouldn’t be treated as the poor cousins of traditional diplomatic work. The challenge is to conceive of the embassy as a facilitator of productive interaction and a broker of relationships—a creative hub of networks—and to find creative, non-traditional ways to use the overseas network to advance Australian national interests across the full spectrum.

Finally, DFAT needs to adopt some of the nimbleness and agility of the tech world. The bureaucracy is still far too slow to adopt reform and changes, partly because it insists on any changes happening wholesale, only after painstaking deliberation, and in a culture that focuses debilitatingly on downside risk and punishes failure. Why not encourage internal innovation, meaning different ways of delivering the same product? Promote experimentation and differential approaches. Test new platforms and business models. Run some pilots, iterate and adjust, gather the evidence, and see what works best. Don’t insist on homogeneity. Tolerate some screw-ups and failures and learn from them.18 This is the secret to innovation and continuous improvement, and it’s essential if our diplomatic services are to keep pace with the modern world.

Recommendations

- Commission an independent review of DFAT’s digital diplomacy efforts.19 The review should examine the department’s digital capabilities, assess the digital operating environment for Australian diplomacy, and make recommendations to improve Australia’s digital diplomacy effort.

- Treat digital diplomacy as core tradecraft, rather than optional add-on. Provide compulsory digital platform training for all outgoing heads of mission.

- Encourage healthy internal competition and innovation. Generate a monthly scorecard highlighting the best digital performers and posts. Promote and celebrate the successes.

- Pilot more sophisticated data analytics tools to analyse and measure impact, reach and engagement—and adjust tactics accordingly. Appoint a Chief Data Scientist to harness and employ data in the service of diplomacy.

- Develop and pilot a new stream of diplomatic reporting that’s punchier and timelier and reaches a broader audience on hand-held devices.

- Create new positions of ambassador to Silicon Valley (based in San Francisco) and ambassador to China’s tech giants (based in Beijing).

- Increase avenues to engage the Chinese public via Chinese social media platforms. This expansion should include dedicated Weibo accounts for the positions of Prime Minister and Foreign Minister.20

- Run a pilot of ‘embassy-lite’ or one-person posts. They’ll be more substantial and enduring than the ‘pop-up embassy’ in Estonia but still substantially lighter in footprint than a fully fledged diplomatic mission.

- Encourage innovation and experimentation in the conduct of digital diplomacy. Highlight and champion successes. Learn from (but don’t punish) the inevitable failures. Use DFAT’s Innovation XChange in this task, but broaden its focus beyond the aid program and extend its remit into mainstream diplomacy.

- Recognise that our overseas network is an underutilised asset. Find creative but non-traditional ways to use it to advance Australian national interests. Conceive of embassies as hubs and connectors for a broad set of interactions. Highlight and promote the strong performers (sending the cultural signal to others).

- Create a Twitter account for the Secretary of DFAT to internally signal the importance of digital diplomacy, to provide a further mouthpiece for Australian interests, and to give the public insight into the important work that Australia’s diplomatic service does every day.

What is ASPI?

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute was formed in 2001 as an independent, non‑partisan think tank. Its core aim is to provide the Australian Government with fresh ideas on Australia’s defence, security and strategic policy choices. ASPI is responsible for informing the public on a range of strategic issues, generating new thinking for government and harnessing strategic thinking internationally.

ASPI International Cyber Policy Centre

The ASPI International Cyber Policy Centre’s mission is to shape debate, policy and understanding on cyber issues, informed by original research and close consultation with government, business and civil society.

It seeks to improve debate, policy and understanding on cyber issues by:

- conducting applied, original empirical research

- linking government, business and civil society

- leading debates and influencing policy in Australia and the Asia–Pacific.

We thank all of those who contribute to the ICPC with their time, intellect and passion for the subject matter. The work of the ICPC would be impossible without the financial support of our various sponsors.

Important disclaimer

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in relation to the subject matter covered. It is provided with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering any form of professional or other advice or services. No person should rely on the contents of this publication without first obtaining advice from a qualified professional person.

© The Australian Strategic Policy Institute Limited 2019

This publication is subject to copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of it may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publishers. Notwithstanding the above, educational institutions (including schools, independent colleges, universities and TAFEs) are granted permission to make copies of copyrighted works strictly for educational purposes without explicit permission from ASPI and free of charge.

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), Social media, Australian Government, no date, online. ↩︎

- See, for instance, Fergus Hanson, ‘DFAT the dinosaur needs to find Facebook friends’, The Australian, 23 November 2010, online. ↩︎

- See twiplomacy, online, for rankings across a number of dimensions. ↩︎

Hu wrote five papers with his supervisor at the University of Agder, all of which listed the Xi’an Research Institute as his affiliation. The papers focused on air-breathing hypersonic vehicles, which travel at over five times the speed of sound and ‘can carry more payload than ordinary flight vehicles’.71 Hu’s work was supported by a Norwegian Government grant for offshore wind energy research.72

Hu wrote five papers with his supervisor at the University of Agder, all of which listed the Xi’an Research Institute as his affiliation. The papers focused on air-breathing hypersonic vehicles, which travel at over five times the speed of sound and ‘can carry more payload than ordinary flight vehicles’.71 Hu’s work was supported by a Norwegian Government grant for offshore wind energy research.72