Tweeting through the Great Firewall

Preliminary Analysis of PRC-linked Information Operations on the Hong Kong Protests

Introduction

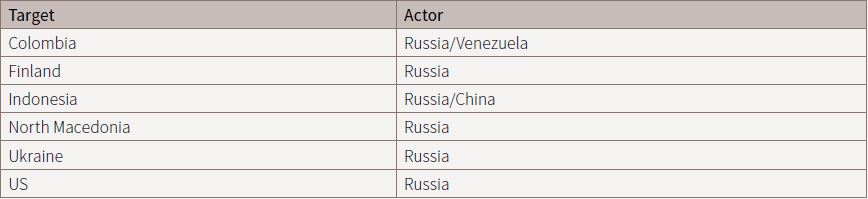

On August 19th 2019, Twitter released data on a network of accounts which it has identified as being involved in an information operation directed against the protests in Hong Kong. After a tip-off from Twitter, Facebook also dismantled a smaller information network operating on its platform. This network has been identified as being linked to the Chinese government.

Researchers from the International Cyber Policy Centre (ICPC) at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute have conducted a preliminary analysis of the dataset. Our research indicates that the information operation targeted at the protests appears to have been a relatively small and hastily assembled operation rather than a sophisticated information campaign planned well in advance.

However, our research has also found that the accounts included in the information operation identified by Twitter were active in earlier information operations targeting political opponents of the Chinese government, including an exiled billionaire, a human rights lawyer, a bookseller and protestors in mainland China. The earliest of these operations date back to April 2017.

This is significant because—if the attribution to state-backed actors made by Twitter is correct—it indicates that actors linked to the Chinese government may have been running covert information operations on Western social media platforms for at least two years.

Methodology

This analysis used a mixed-methods approach combining quantitative analysis of bulk Twitter data with qualitative analysis of tweet content.

The dataset for quantitative analysis was the tweets and accounts identified by Twitter as being associated with a state-backed information operation targeting Hong Kong and is available here.

This dataset consisted of

- account information about the 940 accounts Twitter suspended from their service

- The oldest account was created in December 2007, although half of accounts were created after August 2017

- 3.6 million tweets from these accounts, ranging from December 2007 to May 2019

The R statistics package was used for quantitative analysis, which informed phases of social network analysis (using Gephi) and qualitative content analysis.

Research limitations: ICPC does not have access to the relevant data to independently verify that these accounts are linked to the Chinese government; this research proceeds on the assumption that Twitter’s attribution is correct. It is also important to note that Twitter has not released the methodology by which this dataset was selected, and the dataset may not represent a complete picture of Chinese state-linked information operations on Twitter.

Information operation against Hong Kong protests

Indications of a hastily constructed campaign

Carefully crafted, long-running influence operations on social media will have tight network clusters that delineate target audiences. We explored the retweet patterns across the Twitter take-down data from June 2019 – as the network was mobilising to target the Hong Kong protests – and did not find a network that suggested sophisticated coordination. Topics of interest to the PRC emerge in the dataset from mid-2017 but there is little attempt to target online communities with any degree of psychological sophistication.

There have been suggestions that Taiwanese social media, during recent gubernatorial elections, had been manipulated by suspicious public relations contractors operating as proxies for the Chinese government. It is notable that the network targeting the Hong Kong protests was not cultivated to influence targeted communities; it too acted like a marketing spam network. These accounts did not attempt to behave in ways that would have integrated them into – and positioned them to influence – online communities. This lack of coordination was reflected in the messaging. Audiences were not steered into self-contained disinformation ecosystems external to Twitter, nor were hashtags used to build audience, then drive the amplification of specific political positions. As this network was mobilising against the Hong Kong protests, several nodes in the time-sliced retweet data (see Figure 1) were accounts to promote the sex industry, accounts that would have gained attention because of the nature of their content. These central nodes were not accounts that had invested in cultivating engagement with target audiences (beyond their previous marketing function). These accounts spammed retweets at others outside the network in attempts to get engagement rather than working together to drive amplification of a consistent message.

Figure 1: Retweet network from June 2019, derived from Twitter’s take-down data, showing the significant presence of likely pornography-related accounts within the coordinated network that targeted the Hong Kong protests.

This was a blunt–force influence operation, using spam accounts to disseminate messaging, leveraging an influence-for-hire network. The predominant use of Chinese language suggests that the target audiences were Hong Kongers and the overseas diaspora.

This operation is in stark contrast to the efforts of Russia’s Internet Research Agency (IRA) to target US political discourse, particularly through 2015-2017.

The Russian effort displayed well-planned coordination. Analysis of IRA account data has shown that networks of influence activity cluster around identity or issue-based online communities. IRA accounts disseminated messaging that inflamed both sides of the debates around controversial issues in order to further the divide between protagonist communities. High-value and long-running personas cultivated influence within US political discourse. These accounts were retweeted by political figures, and quoted by media outlets.

The IRA sent four staff to the US to undertake ‘market research’ as the IRA geared up its election meddling campaign. The IRA campaign displayed clear understanding of audience segmentation, colloquial language, and the ways in which online communities framed their identities and political stances.

In contrast, this PRC-linked operation is clumsily re-purposed and reactive. Freedom of expression on China’s domestic internet is framed by a combination of top-down technocratic control managed by the Cyberspace Administration of China and devolved, crowdsourced content regulation by government entities, industry and Chinese netizens. Researchers have suggested that Chinese government efforts to shape sentiment on the domestic internet go beyond these approaches. One study estimated that the Chinese government pays for as many as 448 million inauthentic social media posts and comments a year. The aim is to distract the population from social mobilisation and collective forms of protest action. This approach to manipulating China’s domestic internet appears to be much less effective on Western social media platforms that are not bounded by state control.

Yet, the CCP continues to use blunt efforts to grow the reach, impact and influence of its narratives abroad. Elements of the party propaganda apparatus – including the foreign media wing of the United Front Work Department – have issued (as recently as 16 August) tenders for contracts to grow their international influence on Twitter, with specific targets for numbers of followers in particular countries.

In the longer term, China’s investments in AI may lift its capacity to target and manipulate international social media audiences. However, this operation lacks the sophistication of those deployed by other significant state proponents of cyber-enabled influence operations; particularly Iran and Russia, who have demonstrated the capacity to operate with some degree of subtlety across linguistic and cultural boundaries.

This was the quintessential authoritarian approach to influence – one-way floods of messaging, primarily at Hong Kongers.

Use of repurposed spam accounts

Many of the accounts included in the Twitter dataset are repurposed spam or marketing accounts. Such accounts are readily and cheaply available for purchase from resellers, often for a few dollars or less. Accounts in the dataset have tweeted in a variety of languages including Indonesian, Arabic, English, Korean, Japanese and Russian, and on topics ranging from British football to Indonesian tech support, Korean boy bands and pornography.

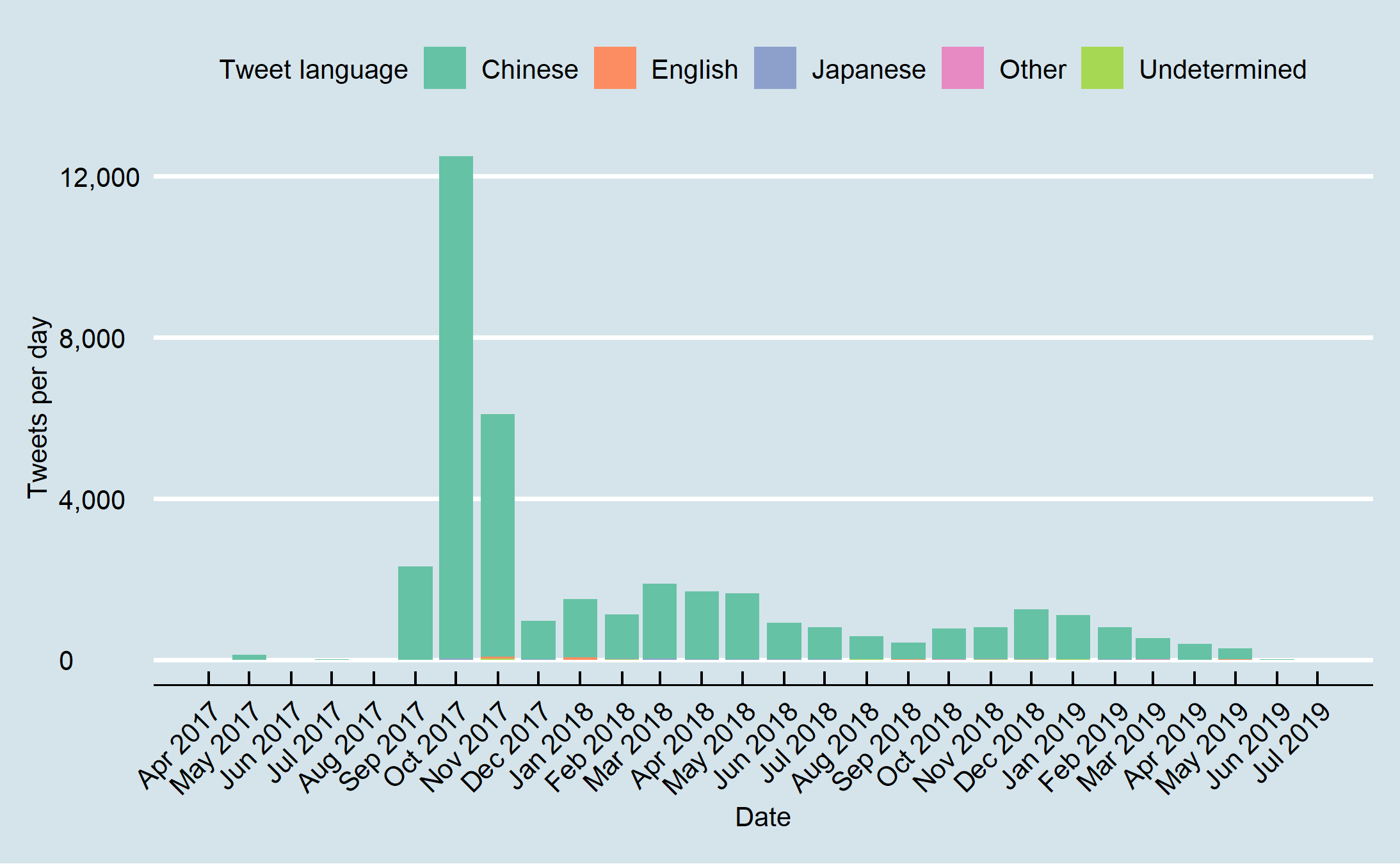

This graph shows the language used in tweets over time, (although Twitter did not automatically detect language in tweets prior to 2013). The dataset includes accounts tweeting in a variety of languages over a long period of time. Chinese language tweets appear more often after mid-2017.

This map shows the self-reported locations of the accounts suspended by twitter, color-coded for the language they tweeted in. These locations do not reliably indicate the true location of the account-holder, but in this data set there is a discrepancy between language and location. The self-reported locations are likely to reflect the former nature of the accounts as spam and marketing bots – i.e., they report their locations in developed markets where the consumers they are targeting are located in order to make the accounts appear more credible, even if the true operators of the account are based somewhere else entirely.

Evidence of reselling is clearly present in the dataset. Over 630 tweets within the dataset contain phrases like ‘test new owner’, ‘test’, ‘new own’, etc. As an example, the account @SamanthxBerg tweeted in Indonesian on the 2nd of October 2016, ‘lelang acc f/t 14k/135k via duit. minat? rep aja’ – meaning that the @SamanthxBerg account with 14,000 followers and following 135,000 users, was up for auction. The next tweet on 6th October 2016 reads ‘i just become the new owner, wanna be my friend?.’

- tweetid: 782380635990200320

- Time stamp: 2016-10-02 00:44:00 UTC

- userid: 769790067183190016

- User display name: 阿丽木琴

- User screen name: SamanthxBerg

- Tweet text: PLAYMFS: #ptl lelang acc f/t 14k/135k via duit. minat? rep aja

Use of these kinds of accounts suggests that the operators behind the information operation did not have time to establish the kinds of credible digital assets used in the Russian campaign targeting the US 2016 elections. Building that kind of ‘influence infrastructure’ takes time and the situation in Hong Kong was evolving too rapidly, so it appears that the actors behind this campaign effectively took a short-cut by buying established accounts with many followers.

Timeline of activity

The amount of content directly targeting the Hong Kong protests makes up only a relatively small fraction of the total dataset released by Twitter, comprising just 112 accounts and approximately 1600 tweets, of which the vast majority are in Chinese with a much smaller number in English.

Content relevant to the current crisis in Hong Kong appears to have begun on 14 April 2019, when the account @HKpoliticalnew (profile description: Love Hong Kong, love China. We should pay attention to current policies and people’s livelihood. 愛港、愛國,關注時政、民生。) tweeted about the planned amendments to the extradition bill. Tweets in the released dataset mentioning Hong Kong continued at the pace of a few tweets every few days, steadily increasing over April and May, until a significant spike on 14 June, the day of a huge protest in which over a million Hong Kongers (1 in 7) marched in protest against the extradition bill.

Hong Kong related tweets per day from 14 April 2019 to 25 July 2019.

Thereafter, spikes in activity correlate with significant developments in the protests. A major spike occurred on 1 July, the day when protestors stormed the Legislative Council building. This is also the start of the English-language tweets, presumably in response to the growing international interest in the Hong Kong protests. Relevant tweets then appear to have tapered off in this dataset, ending on 25 July.

It is worthwhile noting that the tapering off in this dataset may not reflect the tapering off of the operation itself – instead, it is possible that it reflects a move away from this hastily-constructed information operation to more fully developed digital assets which have not been captured in this data.

Lack of targeted messaging and narratives

One of the features of well-planned information operations is the ability to subtly target specific audiences. By contrast, the information operation targeting the Hong Kong protests is relatively blunt.

Three main narratives emerge:

- Condemnation of the protestors

- Support for the Hong Kong police and ‘rule of law’

- Conspiracy theories about Western involvement in the protests

Support for ‘rule of law’:

- tweetid: 1139524030371733504

- Time stamp: 2019-06-14 13:24:00 UTC

- userid: r+QLQEgpn4eFuN1qhvccxtPRmBJk3+rfO3k9wmPZTQI=

- User display name: r+QLQEgpn4eFuN1qhvccxtPRmBJk3+rfO3k9wmPZTQI=

- User screen name: r+QLQEgpn4eFuN1qhvccxtPRmBJk3+rfO3k9wmPZTQI=

- Tweet text: @uallaoeea 《逃犯条例》的修改,只会让香港的法制更加完备,毕竟法律是维护社会公平正义的基石。不能默认法律的漏洞用来让犯罪分子逃避法律制裁而不管。 – 14 June 2019

Translated: ‘The amendment to the Fugitive Offenders Ordinance will only make Hong Kong’s legal system more complete. After all, the law is the cornerstone for safeguarding fairness and justice in society. We can’t allow loopholes in the legal system to allow criminals to escape the arm of the law.’

Conspiracy theories:

- tweetid: 1142349485906919424

- Time stamp: 2019-06-22 08:31:00 UTC

- Userid: 2156741893

- User display name: 披荆斩棘

- User screen name: saydullos1d

- Tweet text: 香港特區警察總部受到包圍和攻擊, 黑衣人嘅真實身份係咩? 係受西方反華勢力指使,然後係背後操縱, 目的明確, 唆使他人參與包圍同遊行示威。把香港特區搞亂, 目的就係非法政治目的, 破環社會秩序。 – 22 June 2019

Translated: ‘Hong Kong SAR police headquarters were surrounded and attacked. Who were the people wearing black? They were acting under the direction of western anti-China forces. They’re manipulating things behind the scenes, with a clear purpose to instigate others to participate in the demonstration and the encirclement. They’re bringing chaos to Hong Kong SAR with an illegal political goal and disrupting the social order.’

[NB: Important to note that this was written in traditional Chinese characters and switches between Standard Chinese and Cantonese, suggesting that the author was a native mandarin speaker but their target audience was Cantonese speakers in Hong Kong.]

- tweetid: 1147398800786382848

- Time stamp: 2019-07-06 06:56:00 UTC

- Userid: 886933306599776257

- User display name: lingmoms

- User screen name: lingmoms

- Tweet text: 無底線的自由,絕不是幸事;不講法治的民主,只能帶來禍亂。香港雖有不錯的家底,但經不起折騰,經不起內耗,惡意製造對立對抗,只會斷送香港前途。法治是香港的核心價值,嚴懲違法行為,是對法治最好的維護,認為太平山下應享太平。 – 6 July 2019

Translated: ‘Freedom without a bottom line is by no means a blessing; democracy without the rule of law can only bring disaster and chaos. Although Hong Kong has a good financial background, it can’t afford to vacillate. It can’t take all of this internal friction and maliciously created agitation, which will only ruin Hong Kong’s future. The rule of law is the core value of Hong Kong. Severe punishment for illegal acts is the best safeguard for the rule of law. Peace should be enjoyed at the foot of The Peak.’’

[NB: This Tweet is also written in Standard Chinese using traditional Chinese characters. The original text says ‘at the foot of Taiping mountain’, meaning Victoria Peak, but is more commonly referred to in Hong Kong as “The Peak” (山頂). However, the use of Taiping mountain instead of ‘The Peak’ to refer to the feature is a deliberate pun, because Taiping means ‘great peace’]

- tweetid: 1152024329325957120

- Time stamp: 2019-07-19 01:16:00 UTC

- Userid: 58615166

- User display name: 流金岁月

- User screen name: Licuwangxiaoyua

- Tweet text: #HongKong #HK #香港 #逃犯条例 #游行 古话说的好,听其言而观其行。看看那些反对派和港独分子,除了煽动上街游行、暴力冲击、袭警、扰乱香港社会秩序之外,就没做过什么实质性有利于香港发展的事情。反对派和港独孕育的“变态游行”这个怪胎,在暴力宣泄这条邪路上愈演愈烈。 – 19 July 2019

Translated: ‘#HongKong #HK #HongKong #FugitiveOffendersOrdinance #Protests The old Chinese saying put it well: ‘Judge a person by their words, as well as their actions’. Take a look at those in the opposition parties and the Hong Kong independence extremists. Apart from instigating street demonstrations, violent attacks, assaulting police officers and disturbing the social order in Hong Kong, they have done nothing that is actually conducive to the development of Hong Kong. This abnormal fetus of a “freak demonstration” that the opposition parties and Hong Kong independence people gave birth to is becoming more violent as it heads down this evil road.’

This approach of vilifying opponents, emphasising the need for law and order as a justification for authoritarian behaviour is consistent with the narrative approaches adopted in earlier information operations contained within the dataset (see below).

Earlier information operations against political opponents

Our research has uncovered evidence that the accounts identified by Twitter were also engaged in earlier information campaigns targeting opponents of the Chinese government.

It appears likely that these information operations were intended to influence the opinions of overseas Chinese diasporas, perhaps in an attempt to undermine critical coverage in Western media of issues of interest to the Chinese government. This is supported by a notice released by China News Service, a Chinese-language media company owned by the United Front Work Department that targets the Chinese diaspora, requesting tenders to expand its Twitter reach.

Campaign against Guo Wengui

The most significant and sustained of these earlier information operations targets Guo Wengui, an exiled Chinese businessman who now resides in the United States. The campaign directed at Guo is by far the most extensive campaign in the dataset and is significantly larger than the activity directed at the Hong Kong protests. This is the earliest activity the report authors have identified that aligns with PRC interests.

Graph showing activity in an information operation targeting Guo from 2017 to the end of the dataset in July 2019

Guo, also known as Miles Kwok, fled to the United States in 2017 following the arrest of one of his associates, former Ministry of State Security vice minister Ma Jian. Guo has made highly public allegations of corruption against senior members of the Chinese government. The Chinese government in turn accused Guo of corruption, prompting an Interpol red notice for his arrest and return to China. Guo has become a vocal opponent of the Chinese government, despite having himself been accused of spying on their behalf in July 2019.

Guo, also known as Miles Kwok, fled to the United States in 2017 following the arrest of one of his associates, former Ministry of State Security vice minister Ma Jian. Guo has made highly public allegations of corruption against senior members of the Chinese government. The Chinese government in turn accused Guo of corruption, prompting an Interpol red notice for his arrest and return to China. Guo has become a vocal opponent of the Chinese government, despite having himself been accused of spying on their behalf in July 2019.

Within the Twitter Hong Kong dataset, the online information campaign targeting Guo began on 24 April 2017, five days after the Interpol red notice was issued at the request of the Chinese government, and continued until the end of July 2019. Guo continues to be targeted on Twitter, although it is unclear if the PRC government is directly involved in the ongoing effort.

Tweets mentioning Guo Wengui over time from 23 April 2017 to 4 May 2017: Graph showing activity in tweet volume by day. Activity appears to take place during the working week (except Wednesdays), suggesting that this activity may be professional rather than authentic personal social media use.

In total, our research identified at least 38,732 tweets from 618 accounts in the dataset which directly targeted Guo. These tweets consist largely of vitriolic attacks on his character, ranging from highly personal criticisms to accusations of criminality, treachery against China and criticisms of his relationship with controversial US political figure Steve Bannon.

- tweetid: 1123765841919660032

- Time stamp: 2019-05-02 01:47:00 UTC

- Userid: 4752742142

- User display name: 漂泊一生

- User screen name: futuretopic

- Tweet text: “郭文贵用钱收买班农,一方面想找靠山,一方面想继续为自己的骗子生涯增加点砝码,其实班农只是爱财并非真想和郭文贵做什么, 很快双方会发现对方都 是在欺骗自己,那时必将反目成 仇.” – 2 May 2019

Translated: “Guo Wengui used his money to buy Bannon. On the one hand, he needed his backing. On the other hand, he wanted to continue to add weight to his career as a swindler. In fact, Bannon just loves money and doesn’t really want to do anything with Guo Wengui. Soon both sides will find out that they’re both deceiving the other, and then they’ll turn into enemies.”

- tweetid: 1153122108655861760

- Time stamp: 2019-07-22 01:58:00 UTC

- Userid: 1368044863

- User display name: asdwyzkexa

- User screen name: asdwyzkexa

- Tweet text: ‘近日的郭文贵继续自己自欺欺人的把戏,疯狂的直播,疯狂的欺骗,疯狂鼓动煽风点火,疯狂的鼓吹自己所谓的民主,鼓吹自己的“爆料革命”。但其越是疯狂,越是难掩日暮西山之态,无论其吹的再如何天花乱坠,也终要为自己的过往负责,亲自画上句点.’ – 22 July 2019

Translated: ‘Lately, Guo Wengui has continued to use his cheap trick of deceiving himself and others with a crazy live-stream where he lied like crazy, incited and fanned the flames like crazy, and agitated for his so-called democracy like crazy—enthusiastically promoting his “Expose Revolution”. But the crazier he gets the harder it is to hide the fact that the sun has already set on him. It doesn’t matter how much he embellishes things; eventually, he will have to take responsibility and put an end to all of this himself.’

Spikes in activity in this campaign appear to correspond with significant developments in the timeline of Guo’s falling out with the Chinese government. For example, a spike around 23 April 2018 (see below chart) correlates with the publishing of a report by the New York Times exposing a complex plan to pull Guo back to China with the assistance of the United Arab Emirates and Trump fundraiser Elliott Broidy.

- tweetid: 988088232075083776

- Time stamp: 2018-04-22 16:12:00 UTC

- Userid: 908589031944081408

- User display name: 如果

- User screen name: bagaudinzhigj

- Tweet text: ‘‘谎言说一千遍仍是谎言,郭文贵纵有巧舌如簧的口才,也有录制性爱视频等污蔑他人的手段,更有给人设套录制音频威胁他人的前科,还有诈骗他人钱财的146项民事诉讼和19项刑事犯罪指控,但您在美国再卖力的表演也掩盖不了事实.’ – 22nd April 2018

Translated: ‘Even if a lie is repeated a thousand times, it’s still a lie. Guo Wengui is an eloquent smooth talker and uses sex tapes and other methods to slander people. He also has a criminal record for trying to threaten and set people up with recorded audio. He has 146 civil lawsuits and 19 criminal charges for swindling other people’s money. No matter how much effort you put in in the United States, you still can’t hide the truth.’

This tweet was repeated 41 times by this user from 7 November 2017 to 15 June 2018, at varying hours of the day, but at only 12 or 42 minutes past the hour, suggesting an automated or pre-scheduled process:

Volume of tweets mentioning Guo Wengui over time from 14 April 2019 to 29 April 2019.

Like the information operation targeting the Hong Kong protests, the campaign targeting Guo is primarily in Chinese language. There are approximately 133 tweets in English, many of which are retweets or duplicates. On 5th November 2017, for example, 27 accounts in the dataset tweeted or retweeted: ‘#郭文贵 #RepatriateKwok、#Antiasylumabused、 sooner or later, your fake mask will be revealed.’

As the Hong Kong protests began to increase in size and significance, the information operations against Guo and the protests began to cross over, with some accounts directing tweets at both Guo and the protests.

- tweetid: 1148407166920876032

- Time stamp: 2019-07-09 01:42:00 UTC

- Userid: 886933306599776257

- User display name: lingmoms

- User screen name: lingmoms

- Tweet text: ‘唯恐天下不乱、企图颠覆香港的郭文贵不仅暗中支持香港占中分子搞暴力破坏,还公开支持暴力游行示威,难道这一小撮入狱的暴民就是文贵口中的“香港人”?’– 9 July 2019

Translated: ‘Guo Wengui, who fears only a world not in chaos and schemes to toppleHong Kong, is not only secretly supporting the violent and destructive Occupy extremists in Hong Kong, he’s also openly supporting violent demonstrations. Is this small mob of criminals the “Hong Kong people” Guo Wengui keeps talking about?’

The dataset provided by Twitter ends in late July 2019, but all indications suggest that the information campaign targeting Guo will continue.

Campaign against Gui Minhai

Although the campaign targeting Guo Wengui is by far the most extensive in the dataset, other individuals have also been targeted.

One is Gui Minhai, a Chinese-born Swedish citizen. Gui is one of a number of Hong Kong-based publishers specialising in books about China’s political elite who disappeared under mysterious circumstances in 2015. It was later revealed that he had been taken into Chinese police custody. The official reason for his detention is his role in a fatal traffic accident in 2003 in which a schoolgirl was killed. Gui has been in and out of detention since 2015, and has made a number of televised confessions which many human rights advocates believe to have been forced by the Chinese government.

The information operation targeting Gui Minhai is relatively small, involving 193 accounts and at least 350 tweets. With some exceptions, the accounts used in the activity directed against Gui appear to be primarily ‘clean’ accounts created specifically for use in information operations, unlike the repurposed spam accounts utilised by the activity targeted at Hong Kong.

The campaign runs for one month, from 23 January to 23 February 2018. The preciseness of the timing is indicative of an organised campaign rather than authentic social media activity. The posting activity also largely corresponds with the working week, with breaks for weekends and holidays like Chinese New Year.

A graph showing campaign activity in tweets per day. Weekends and public holidays are indicated by grey shading.

The campaign started on 23 January 2018, the day on which news broke that Chinese police had seized Gui off a Beijing-bound train while he was travelling with Swedish diplomats to their embassy. The campaign then continued at a slower pace across several weeks, ending on 23 February 2018. The tweets are entirely in Chinese language and emphasise Gui’s role in the traffic accident, painting him as a coward for attempting to leave the country and blaming Western media for interfering in the Chinese criminal justice process. Some also used Gui’s name as a hashtag.

- tweetid: 956700365289807872

- Time stamp: 2018-01-26 01:28:00 UTC

- Userid: 930592773668945920

- User display name: 赵祥

- User screen name: JonesJones4780

- Tweet text: ‘#桂民海 因为自己一次醉驾,让一个幸福家庭瞬间支离破碎,这令桂敏海痛悔不已。但是,他更担心自己真的因此入狱服刑。于是,在法院判决后不久、民事赔偿还未全部执行完的时候,桂敏海做出了另一个错误选择.’ – 26 January 2018

Translation: ‘#GuiMinhai deeply regrets that a happy family was shattered because of his drunk driving. However, he’s even more worried that he’s actually going to have to serve a prison sentence for it. Therefore, not long after the court’s decision and before any civil compensation was paid out, Gui Minhai made another bad choice’

- tweetid: 956411588386279424

- Time stamp: 2018-01-25 06:21:00 UTC

- Userid: 1454274516

- User display name: 熏君

- User screen name: nkisomekusua

- Tweet data: ‘#桂敏海 西方舆论力量仍想运用它们的话语霸权和双重标准,控制有关中国各种敏感信息的价值判断,延续对中国政治体制的舆论攻击,不过西方媒体这样的炒作都只是自导自演,自娱自乐.’ – 25 January 2018

Translation: ‘#GuiMinhai Western public opinion forces still want to use their discourse hegemony and double standards to control value judgments of all kinds of sensitive information about China and are continuing their public opinion attacks on the Chinese political system. However, this kind of hype in the Western media is just a performance they’re doing for themselves for their own personal entertainment.’

Others amplify the messages of Gui’s “confession”, claiming that he chose to hand himself in to police of his own volition due to his sense of guilt.

- tweetid: 959276160038289408

- Time stamp: 2018-02-02 04:03:00 UTC

- Userid: 898580789952118784

- User display name: 雪芙

- User screen name: Ryy7v3wQkXnsGO8

- Tweet text: ‘#桂敏海 父亲去世他不能奔丧这件事情,对桂敏海触动很大。他的母亲也80多岁了,已经是风烛残年,更让他百般思念、日夜煎熬,心里总是有一种很强烈的愧疚不安。所以他选择回国自首.’ – 2 February 2018

Translation: The death of #GuiMinhai’s father and the fact he couldn’t return home for the funeral greatly affected him. His mother is also over 80 years old and is already in her twilight years, causing him to suffer day and night in every possible way. There was always a strong sense of guilt and uneasiness in his heart. So he chose to return to China and give himself up.’

It seems likely that this was a short-term campaign intended to influence the opinions of overseas Chinese who might see reports of Gui’s case in international media.

Campaign against Yu Wensheng

On precisely the same day as the information operation against Gui started, another mini-campaign appears to have been launched. This one was aimed against human rights lawyer and prominent CCP-critic Yu Wensheng.

Yu was arrested by Chinese police whilst walking his son to school on 19 January 2018. Only hours before, Yu had tweeted an open letter critical of the Chinese government, and called for open elections and constitutional reform. Shortly after, an apparently doctored video was released, raising questions about whether Chinese authorities were attempting to launch a smear campaign against Yu.

In this dataset, tweets targeting Yu Wensheng begin on 23 January 2018—the same day as the campaign against Gui Minhai—and continue through until 31 January (only four tweets take place after this, the latest on 10 February 2018). This was a small campaign, consisting of roughly 218 tweets from 80 accounts, many of which were the same content amplified across these accounts. As with Gui, Yu’s name was often used as a hashtag.

This graph shows campaign activity in tweets per day over time. Selected weekends are highlighted in grey.

The content shared by the campaign was primarily condemning Yu for his alleged violence against the police as shown by the doctored video.

- tweetid: 956707469677359104

- Time stamp: 2018-01-26 01:56:00

- Userid: 0jFZp2sQdCYj8hUveyN4Llxe2UvFbQgTqxaymZihMM0

- User display name: 0jFZp2sQdCYj8hUveyN4Llxe2UvFbQgTqxaymZihMM0

- User screen name: 0jFZp2sQdCYj8hUveyN4Llxe2UvFbQgTqxaymZihMM0

- Tweet text: ‘#余文生 1月19日,一余姓男子在接受公安机关依法传唤时暴力袭警致民警受伤,被公安机关依法以妨害公务罪刑事拘留。澎湃新闻从北京市公安机关获悉,涉案男子系在被警方强制传唤时,先后打伤、咬伤两名民警.’ – 26 January 2018.

Translation: ‘#YuWensheng On January 19, a man surnamed Yu violently assaulted a police officer while receiving a legal summons from the public security bureau, and was arrested for obstructing government administration. Beijing Public Security Bureau told The Paper [a Chinese publication] that the man involved in the case wounded the officers repeatedly by biting them when he was being forcibly summoned by the police.’

As with the other campaigns, however, accusations of supposed Western influence were also notable:

- tweetid: 956742165845090304

- Time stamp: 2018-01-26 04:14:00 UTC

- Userid: 2l1eDka0eiClBUYoDXlwYaKcUaeelnz44aDM9OJRM

- User display name: 2l1eDka0eiClBUYoDXlwYaKcUaeelnz44aDM9OJRM

- User screen name: 2l1eDka0eiClBUYoDXlwYaKcUaeelnz44aDM9OJRM

- Tweet text: ‘#余文生 在中国,有一批人自称维权律师,他们自诩通过行政及法律诉讼来维护公共利益、宪法及公民权利,并鼓吹西方民主、自由,攻击中国黑暗、专制、暴力执法、缺乏法治精神,视频主人公余文生律师也正是其中的一员.’ – 26 January 2018

Translation: ‘#YuWensheng It can be seen from Yu Wensheng’s past activities that he is one of the so-called rights lawyers in China. Yu Wensheng thinks that with the support of foreign media and rights lawyers, he can become a hero and that naturally, some people will cheer for him. Little did he know that this time the police were wearing a law enforcement recording device that they used to record an overview of the incident and quickly published it to the world. Yu’s ugly face was undoubtedly revealed to the public.’

- tweetid: 958222061972832256

- Time stamp: 2018-01-30 06:15:00 UTC

- Userid: Kmto+XqJ6hcowk0GvAGVEasNxHUW11beLphANrm3uhE=

- User display name: Kmto+XqJ6hcowk0GvAGVEasNxHUW11beLphANrm3uhE=

- User screen name: Kmto+XqJ6hcowk0GvAGVEasNxHUW11beLphANrm3uhE=

- Tweet text: ‘#余文生 从余文生过去的活动中可以看到,他是国内所谓维权律师中的一员。余文生认为身后有国外媒体以及维权律师群体的支持,他就能成为英雄,自然有人为他摇旗呐喊。殊不知这次警察佩戴了执法记录仪,录下了事件的概况,并迅速公布于世,余的丑陋嘴脸在公众暴露无疑.’ – 30 January 2018.

Translation: ‘#YuWensheng In China, a group of people claim to be rights defenders. They claim to protect the public interest, constitution and civil rights through administrative and legal proceedings. They advocate for Western democracy and freedom and attack China’s darkness, autocracy, violent law enforcement and the lack of the rule of law. Lawyer Yu Wensheng, the star of the video, is also one of them.’

As with the other campaigns seen in this dataset, it seems probable that the motivation behind this effort was to convince overseas Chinese to believe the Chinese Communist Party’s version of events, bolstering the doctored video of Yu and amplifying the smear campaign.

Campaign against protesting PLA veterans

Another information campaign aimed at influencing public opinion appears to have taken place in response to the arrest of ten Chinese army veterans over protests in the eastern province of Shandong.

The protests took place in October 2018, when around 300 people demonstrated in Pingdu city to demand unpaid retirement benefits for veterans of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). The protests allegedly turned violent, leading to injuries and damage to police vehicles. On 9 December 2018, Chinese state media announced that ten veterans had been arrested for their role in the protest. China Digital Times, which publishes leaked censorship instructions, reported that state media had been instructed to adopt a “unified line” on the arrests.

On the same day, a small but structured information operation appears to have kicked into gear. Beginning at 8:43am Beijing time, accounts in the dataset began tweeting about the arrests. This continued with tweets spaced out every few minutes (a total of 683) until 3:52pm Beijing time. At 9:52pm Beijing time the tweets started up again, this time continuing until 11:49pm.

This graph shows campaign activity over the day by hour of the day adjusted for Beijing UTC+8 time.

Activity by the accounts in the dataset included tweets as well as retweeting and responding to one another’s tweets, creating the appearance of authentic conversation. There was significant repetition within and across accounts, however, with many accounts tweeting a phrase and then tweeting the exact same phrase repeatedly in replies to the tweets of other accounts.

The content of the tweets supported and reinforced the message being promoted by state media, in condemning the protestors as violent criminals and calling for them to be punished.

- tweetid: 1071589476495835136

- Time stamp: 2018-12-09 02:16:00 UTC

- Userid: 53022020

- User display name: sergentxgner

- User screen name: sergentxgner

- Tweet text: ‘中国是社会主义法治国家,绝对没有法外之地和法外之人,法律面前人人平等。自觉遵守国家法律、依法合理表达诉求、维护社会正常秩序,是每一位公民的义务和责任。对任何违法犯罪行为,公安机关都将坚决依法予以打击,为中国公安点赞,严厉惩治无视法律法规之人,全力保障人民群众生命、财产安全.’ – 9 December 2018

Translated: ‘China is a socialist country ruled by law. There’s no place and no people in it that are above the law. All people are equal before the law. It is the duty and responsibility of every citizen to consciously abide by the laws of the state, to express their demands reasonably and according to the law, and to maintain the normal social order. Public security organs will resolutely crack down on any illegal or criminal acts in accordance with the law. Like [this post] for China’s public security, severely punish those who ignore laws and regulations, and fully protect the lives and property of the people.’

- tweetid: 1071614920846786560

- Time stamp: 2018-12-09 03:58:00 UTC

- Userid: 4249759479

- User display name: 林深见鹿

- User screen name: HcqcPapleyAshle

- Tweet text: ‘这些人的行为严重造成人民群众的生命财产安全,就应该雷霆出击,绝不手软.’ – 9 December 2018

Translated: ‘The behaviour of these people has seriously caused [harm to] the safety of the lives and property of the people. They should strike out like a thunderclap and not relent.’

[NB: This tweet may have been typed incorrectly and missed out a character or two. It should probably say that the behaviour endangered the lives and property of these people.]

Again, it appears likely that the motivation behind this campaign was to influence the opinions of overseas Chinese against critical international reporting (although international coverage of the arrests appears to have been minimal, which perhaps helps to explain the short-lived nature of the campaign) and videos of the event being circulated on WeChat that contradicted the official narrative.

Dormant accounts and Chinese language tweets

The information operation against Guo Wengui appeared to begin on 24 April 2017. Our research also tried to determine whether earlier PRC-related information operations had taken place.

Chinese language tweets.

One measure we examined was the percentage of Chinese language tweets per day in the dataset. Twitter assigns a ‘tweet_language’ value to tweets, and manual examination of a sample of tweets showed that this was approximately 90% accurate.

Figure 11: Percent Chinese language tweets per day from Jan 2017 onwards.

Figure 11: Percent Chinese language tweets per day from Jan 2017 onwards.

Figure 11 shows that prior to April 2017 there was no significant volume of Chinese language tweets in the network of accounts that Twitter identified. A noticeable increase is seen by July 2017, and a significant volume of the tweets are identified as Chinese from then on, with a peak at over 80% in October 2017.

This measure does not support the existence of significant PRC-related operations prior to April 2017, unless their initial operations occurred in languages other than Chinese.

Account creation and tweet language

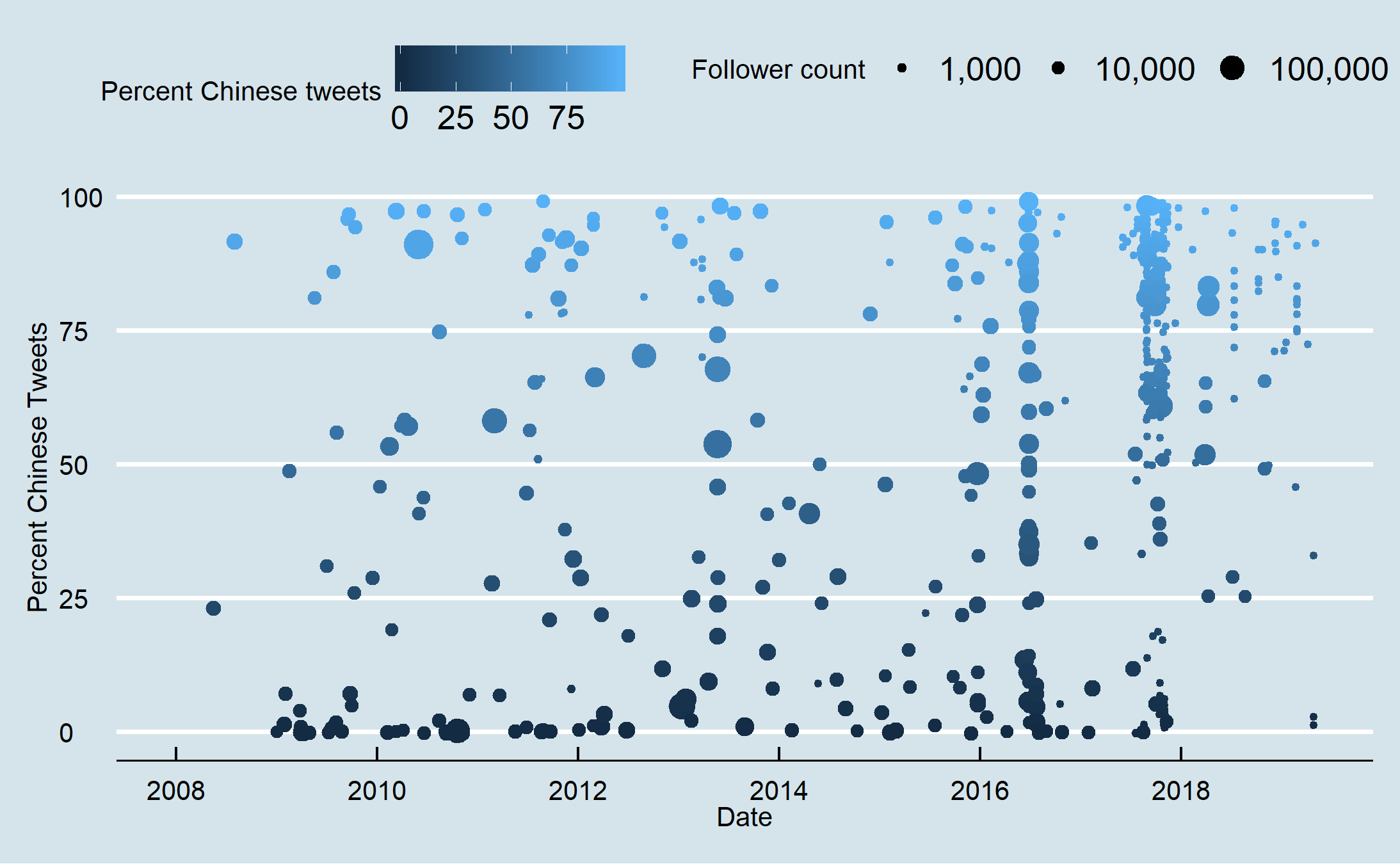

A second measure examined when accounts were created and the language they tweeted in.

Figure 12: Account creation day by percent Chinese tweets and follower size from 2008 to July 2019.

Figure 12: Account creation day by percent Chinese tweets and follower size from 2008 to July 2019.

Figure 12 shows when accounts were created with time on the x-axis, compared to percent Chinese tweets over the lifetime of the account y-axis, with size of point reflecting follower numbers.

Figure 13: Account creation day by percent Chinese tweets and follower size from April 2016 to July 2019.

Figure 13: Account creation day by percent Chinese tweets and follower size from April 2016 to July 2019.

Figure 13 is the same data from April 2016 to July 2019.

In Figure 12 and Figure 13 we can see a vertical stripe in July 2016, and more in August through October 2017. These stripes indicate many accounts being created at close to the same time. From July 2017 new accounts tweet mostly in Chinese.

These data indicate that accounts were systematically created to be involved in this network. Accounts created after October 2017 tweet mostly in Chinese, with just a couple of exceptions. There are also a group of accounts that were created in July 2016 that were involved in the network that were created close to simultaneously.

Sleeper Accounts

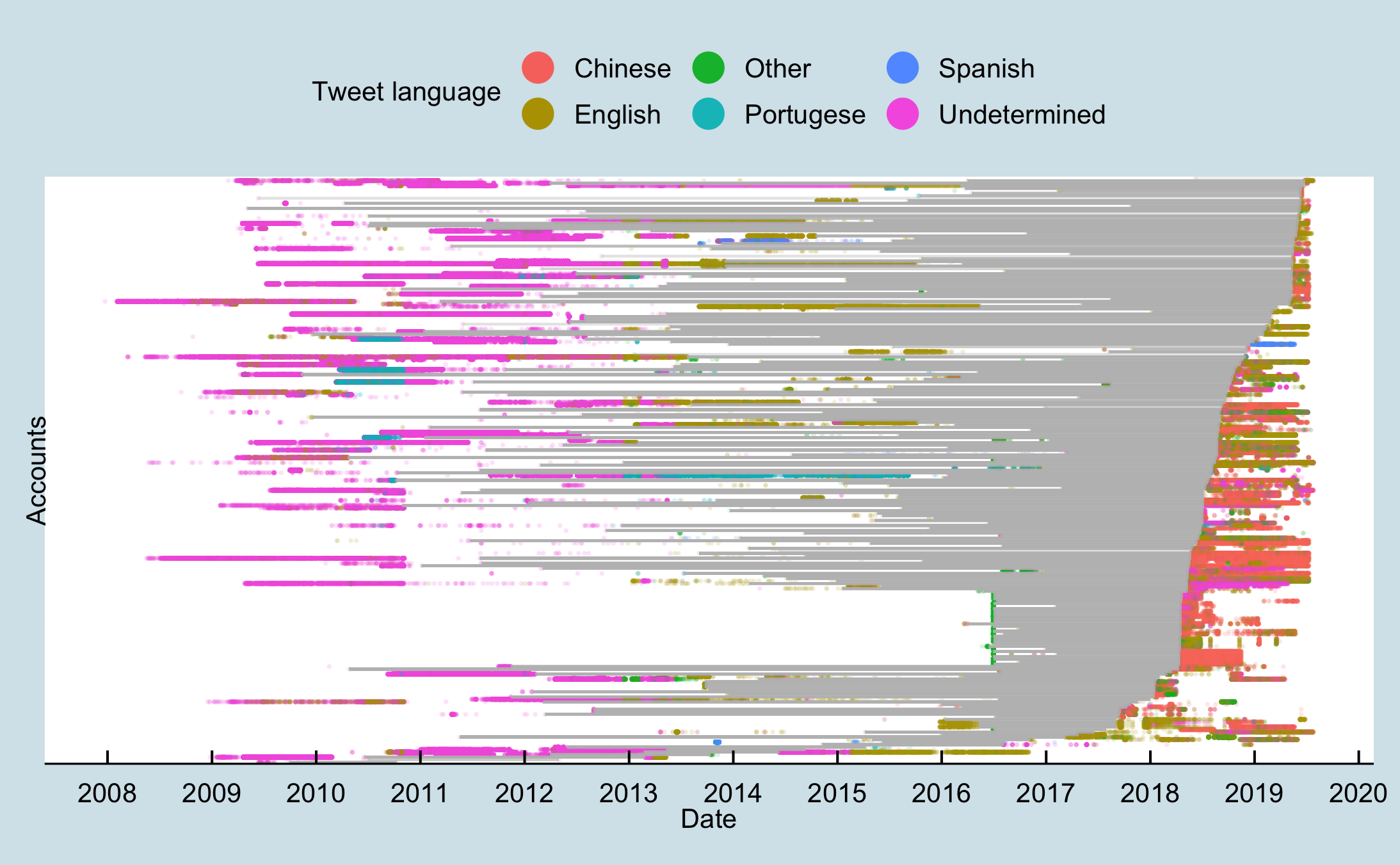

The dataset contained 233 accounts that had greater than year-long breaks between tweets. These sleeper accounts were created as early as December 2007, and had breaks as long as ten years between tweets.

Figure 14: Tweets over time as represented as dots coloured by tweet language for accounts with a greater than one-year gap between tweets. More than year-long gaps between tweets are represented by grey lines.

Figure 14: Tweets over time as represented as dots coloured by tweet language for accounts with a greater than one-year gap between tweets. More than year-long gaps between tweets are represented by grey lines.

Figure 14 shows the pattern of tweets for these accounts over time. These accounts tweeted in a variety of languages including Portugese, Spanish and English, but not Chinese prior to their break in activity. After they resumed tweeting there is a significant volume of Chinese language tweets.

The bulk of these sleeper accounts begin to tweet again from late 2017 onwards. These data support the hypothesis that PRC-related groups began recruiting dormant accounts into their network from mid- to late-2017 and onwards.

Figure 15: Tweets over time as represented as dots coloured by tweet language for accounts with a greater than one-year gap between tweets that were created between June and August 2016.

Figure 15: Tweets over time as represented as dots coloured by tweet language for accounts with a greater than one-year gap between tweets that were created between June and August 2016.

Figure 15 shows the tweeting pattern of accounts created in June and August 2016. These accounts can be seen as a vertical stripe in Figure 13.

The presence of long gaps in tweets immediately after account creation before reactivation and tweeting mostly in Chinese from early 2018 does not support the hypothesis that PRC-related elements were engaged in active information operations before April 2017. It is possible that these accounts were created by PRC-related entities expressly for use in subsequent information operations, but our assessment is that it is more likely that these inactive accounts were created en masse for other purposes and then acquired by PRC-related groups.

This research did not identify any evidence for other PRC-related information operations earlier than April 2017.

Conclusion

The ICPC’s preliminary research indicates that the information operation targeting the Hong Kong protests, as reflected in this dataset, was relatively small hastily constructed, and relatively unsophisticated. This suggests that the operation, which Twitter has identified as linked to state-backed actors, is likely to have been a rapid response to the unanticipated size and power of the Hong Kong protests rather than a campaign planned well in advance. The unsophisticated nature of the campaign suggests a crude understanding of information operations and rudimentary tradecraft that is a long way from the skill level demonstrated by other state actors. This may be because the campaigns were outsourced to a contractor, or may reflect a lack of familiarity on the part of Chinese state-backed actors when it comes to information operations on open social media platforms such as Twitter, as opposed to the highly proficient levels of control demonstrated by the Chinese government over heavily censored platforms such as WeChat or Weibo.

Our research has also uncovered evidence that these accounts had previously engaged in multiple information operations targeting political opponents of the Chinese government. Activity in these campaigns show clear signs of coordinated inauthentic behaviour, for example patterns of posting which correspond to working days and hours in Beijing. These information operations were likely aimed at overseas Chinese audiences.

This research is intended to add to the knowledge-base available to researchers, governments and policymakers about the nature of Chinese state-linked information operations and coordinated inauthentic activity on Twitter.

Notes

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of ICPC colleagues Fergus Ryan, Alex Joske and Nathan Ruser.

Twitter did not provide any funding for this research. It has provided support for a separate ICPC project.

What is ASPI?

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute was formed in 2001 as an independent, non‑partisan think tank. Its core aim is to provide the Australian Government with fresh ideas on Australia’s defence, security and strategic policy choices. ASPI is responsible for informing the public on a range of strategic issues, generating new thinking for government and harnessing strategic thinking internationally.

ASPI International Cyber Policy Centre

The ASPI International Cyber Policy Centre’s mission is to shape debate, policy and understanding on cyber issues, informed by original research and close consultation with government, business and civil society.

It seeks to improve debate, policy and understanding on cyber issues by:

- conducting applied, original empirical research

- linking government, business and civil society

- leading debates and influencing policy in Australia and the Asia–Pacific.

The work of ICPC would be impossible without the financial support of our partners and sponsors across government, industry and civil society. ASPI is grateful to the US State Department for providing funding for this research project.

Important disclaimer

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in relation to the subject matter covered. It is provided with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering any form of professional or other advice or services. No person should rely on the contents of this publication without first obtaining advice from a qualified professional person.

© The Australian Strategic Policy Institute Limited 2019

This publication is subject to copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of it may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publishers. Notwithstanding the above, educational institutions (including schools, independent colleges, universities and TAFEs) are granted permission to make copies of copyrighted works strictly for educational purposes without explicit permission from ASPI and free of charge.