ASPI recommends: Can intervention work? (part II)

We saw yesterday how the misinterpreted ‘lessons’ of international interventionism from the Bosnia experience led to the notion of ‘liberal imperialism’ that ultimately came unstuck in Iraq, only to be (somewhat) saved by a ‘surge’ in military effort. However, according to author Rory Stewart, even that model failed in Afghanistan, leaving a chaotic and counter productive situation. Although the international community had some considerable success early on in the campaign—promoting development and driving Al Qaeda from Afghanistan, ultimately killing nearly all its senior leadership—the attempt to transform the country has failed. Projects that depend on foreign technical expertise and which can be executed from Kabul or foreign capitals have tended to be successful, but the international community has floundered when confronted by the concrete realities—and forms of resistance—shaping Afghan rural life. Stewart demonstrates that before 2011 the international community remained isolated from concrete realities, habitually optimistic about Western capability, and devoted to abstract forms of modern expertise shrouded in a jargon so dense they were difficult to interpret, let alone translate. Stewart condemns the tendency to rely on a culture of consultancy as opposed to country experts, which he argues is as pronounced within the British Foreign Office as the US government and the United Nations.

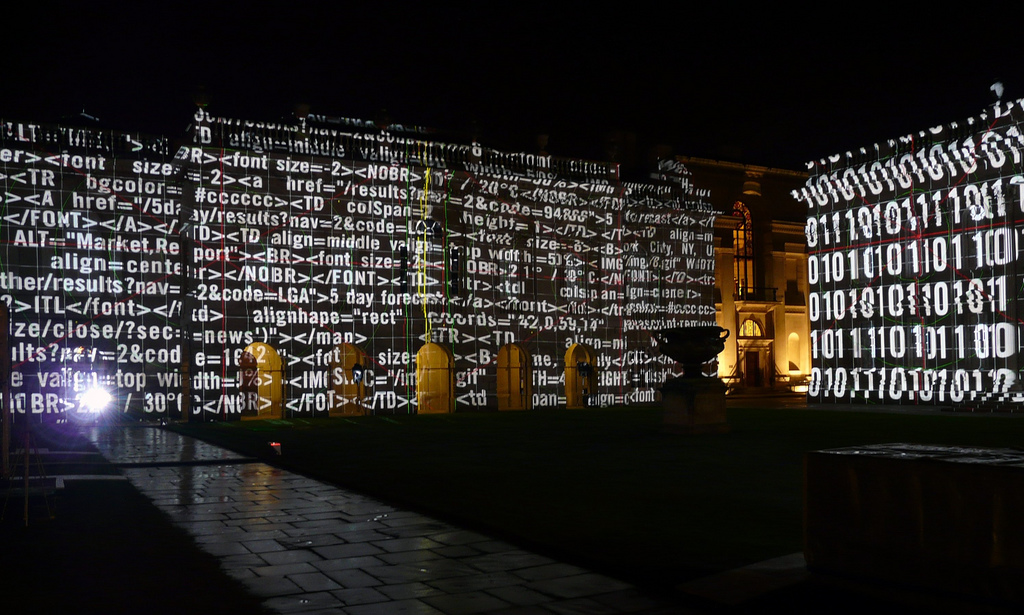

Echoing George Orwell’s classic analysis of ‘Politics and the English Language’, Stewart detonates the buzz-talk that has permeated the international community’s intervention in Afghanistan. Casting doubt on the use of concepts such as the ‘rule of law’ and ‘ungoverned spaces’, ‘disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration’ and the ‘legitimate monopoly on the use of violence’, Stewart demonstrates that the international community’s lofty abstractions were so difficult to apply to rural Afghan society that it was almost impossible to know when they were failing. This made space for absurd foreign projects and liberated policymakers from uncomfortable realities, allowing them to sketch indistinct utopias in a language so unexceptional and morally appealing it captivated Norwegian aid agencies and Delta Force alike. Lofty abstractions lacking concrete definitions could be arranged in every conceivable sequence, allowing members of the foreign intervention to justify almost any policy they pleased. The strategy was an abstraction but the war effort grew, and grew. Read more