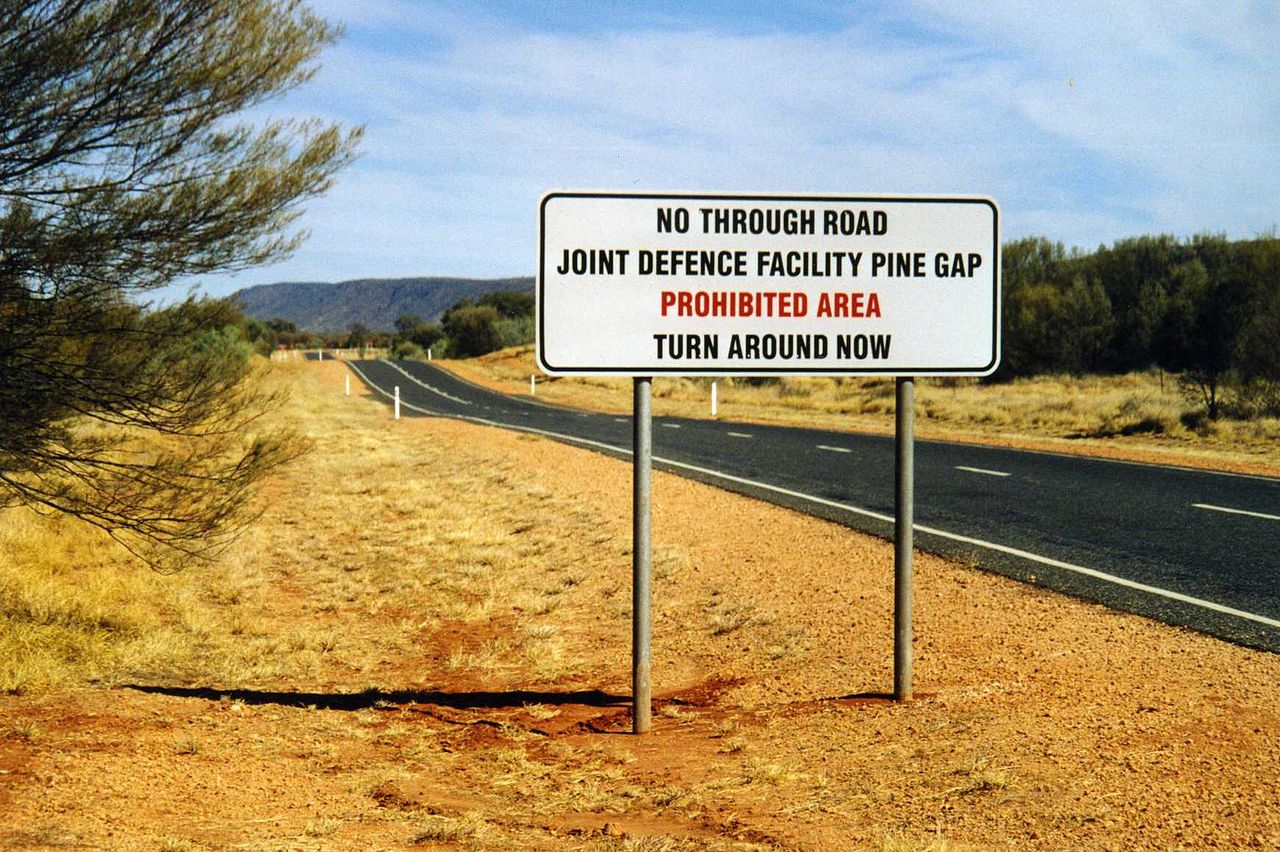

Pine Gap – technically speaking, Australia has a choice

Cam Hawker’s recent Strategist post, ‘Stuck in the middle with you’, suffers from five major fallacies. First, it assumes that Australia–US joint facilities predetermine the strategic relationship between Canberra and Washington. Second, it assumes that the facilities’ predetermination of policy is automatic—meaning, as Cam puts it, that ‘there is no choice and has not been for decades.’ Third, it argues that the pre-eminence of the joint facilities ‘hardwires’ Australian decisions about the use of force to US decisions—that once the US goes to war, Australia must follow. Fourth, it insists that in the typical rush to war, Australia would in any case have no time to think through possible constraints on the use of the joint facilities in a conflict to which Australia was not a party. And fifth, it suggests that recent signs of innovation within ANZUS, like the stationing of the US marines in Darwin, are largely irrelevant because our strategic policy is already a prisoner of Washington’s.

These are big, meaty assertions. Cam’s piece is one of the strongest examples I’ve seen in recent times of what’s called ‘the dependency thesis’—that Australian strategic and defence policy is dependent upon that of its great and powerful ally. But on all five points the article is fundamentally wrong-headed. The Australia–US strategic relationship is a broad one, and its character and content is not predetermined by the existence of the joint facilities. True, the facilities began their life as actual US bases, but evolved into joint facilities during the 1980s. As joint facilities, they serve both US and Australian defence forces, and US and Australian national interests. Changing US submarine deployment patterns have, over the years, made the Northwest Cape communication facility less relevant to the US and more relevant to us. And technological innovation meant the functions of the Nurrungar defence satellite support facility could essentially be fulfilled from the Pine Gap site. Pine Gap remains an important facility, but thinking that the arcane SIGINT relationship runs the broader strategic one is simply mistaken. Read more