Halifax International Security Forum: global leadership (part I)

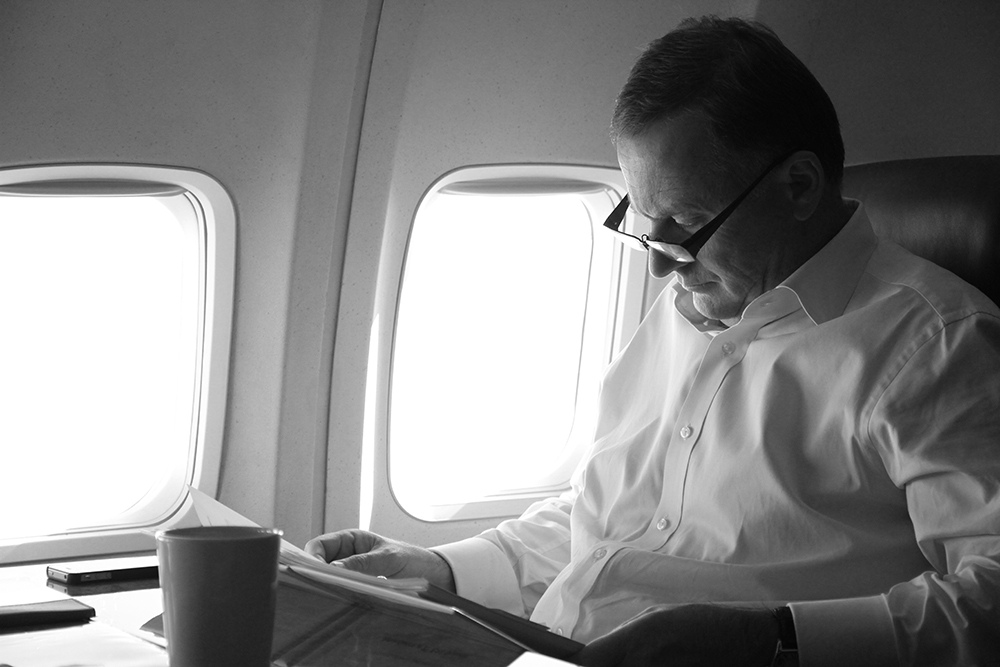

Recently I was fortunate to have attended the Halifax International Security Forum which is rapidly becoming one of the most significant meetings on the global strategic calendar. Conceived and now hosted by the Canadian Minister for National Defence, Peter MacKay, and Foreign Affairs magazine, the fourth Forum, has just concluded in Halifax, Nova Scotia—MacKay’s home province. Over a three day period a diverse and especially invited group of government officials, military personnel, politicians, academics, think tankers and others, worked to unpick the complexities of some of the most challenging security issues of contemporary international affairs. The panels brought together many of the most eminent people in their respective fields and if the conclusions were not always reassuring, the debate was invariably lively, wide ranging and consistently well informed.

With this year’s theme ‘What is the new normal and when will it get here?’ the meeting kicked off by exploring the contemporary geostrategic landscape and continuities with the recent past. Understandably perhaps, assessments of the key issues and trends varied among the panellists, except that we live in challenging times, where much that confronts us resonates with the past and where the tool box of the policymakers seeking to address them is often bereft of reliable instruments. With China rising and India and Brazil emerging, for example, the geopolitical tectonic plates are shifting irretrievably towards a new global order, but to what extent can we expect the new normalcy will bring peace and stability? To the extent that conclusions were possible, they tended to be unsettling. But as Australia’s High Commissioner in Ottawa, Louise Hand was able to remind the audience, the news is not all bad. In East Asia, she noted, economic growth is strong, incomes are rising and millions are being lifted from poverty in what is proving, at least so far, a sustainable way. Read more