AUKMIN: awkward Anglos

Later this month Perth will host the fifth meeting of AUKMIN, the annual gathering of Foreign and Defence ministers from Australia and the United Kingdom. It will be a curious gathering, overshadowed by a doubt that both sides won’t raise but which still dogs this oldest of Australia’s bilateral relations: neither country takes the other seriously as a potentially closer defence partner. Australia doubts that the UK’s new-found interest in Asia really goes beyond trade and investment to include deep engagement on security. The UK wonders how much interest Australia has left for Europe after the Asian Century White Paper tied us so firmly to the region’s economic success story.

The litmus test for substance in a bilateral defence relationship is what the two defence forces actually do together. Reading the last AUKMIN communiqué from January 2012, I’m forced to the reluctant conclusion that the answer is ‘not very much’. The communiqué shows that ministers ‘discussed’ all manner of strategic issues, from the Arab Spring to Fiji—going so far as to commit themselves to ‘sharing strategic insights and aligning… thinking’. The reader searches in vain for just one practical measure of planned and funded defence engagement. Both the 2012 and 2011 communiqués deploy the phrase that the two countries are ‘committed to working together in concrete and practical ways’ on security cooperation—effectively demonstrating the iron rule of communiqué writing: the less substance there is in the relationship, the more spruiking is needed.

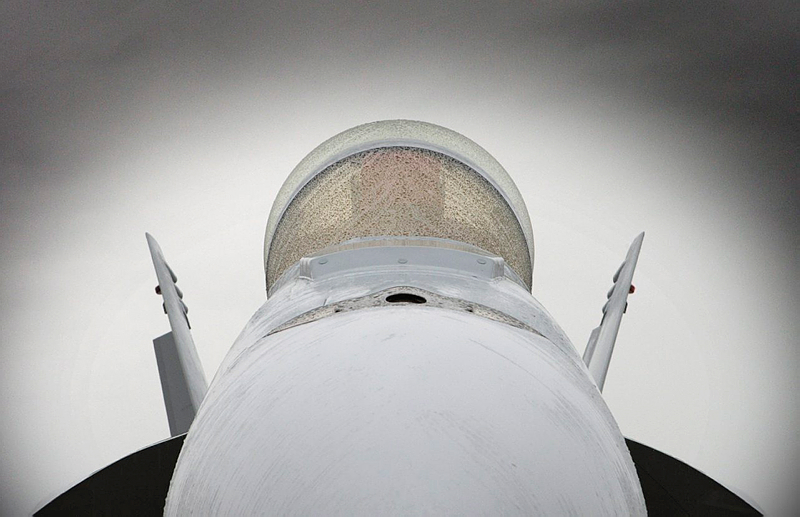

The fact is that defence cooperation between the UK and Australia is limited and at risk of shrinking further. Because of cost saving measures, secondments between the forces are reducing, as is training and exercising. Intelligence exchanges and strategic dialogues are low cost and show that each country has a lot to gain from deeper engagement but they can’t wholly replace the practical value that comes from close service to service engagement. Of course there is a deep cultural affinity between the two Defence organisations, but wallowing in heritage and history is no substitute for an active and modern strategic relationship. Read more