Waiting longer for more—project timelines then and now

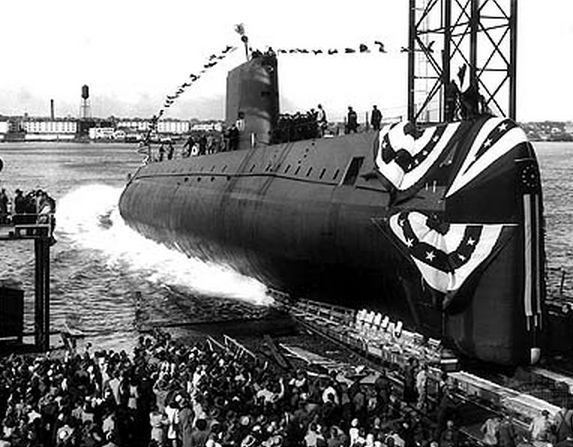

In his recent ASPI lunchtime address, David Gould—DMO’s General Manager Submarines—observed that the Collins submarine project ‘delivered a class of six submarines of unique design in a shade under 20 years’. He added that the project that produced Britain’s nuclear Astute class submarines has delivered two boats since it began 17 years ago, and ‘will comfortably exceed 20 years to complete all seven’.

Those numbers weren’t a surprise, and the ones Mark Thomson and I used in our calculations of projected Australian submarine availability last year were very similar. Likewise if we look at the aerospace world. The development contract for the Joint Strike Fighter program was signed in 1996, with Lockheed Martin and Boeing receiving approval to build competing designs. Lockheed’s X-35 prototype was selected for further development ahead of Boeing’s X-32 design (incidentally the world’s ugliest fighter aeroplane) and the Pentagon awarded a contract for System Development and Demonstration in late 2001. On current plans, the (now) F-35 will enter service with the US Air Force in 2016—two decades after the program began. Read more