From the bookshelf: ‘Vietnam vanguard’—a unit history of lasting value

Unit histories are usually written mainly for members of the unit and their descendants: only a few have lasting historical value. It is, as sporting commentators would put it, a big call to say that the history of a unit of one of the smaller nations in a controversial war, based largely on the memories of its members and written collaboratively 50 years after the events it relates, deserves the attention of those interested in historical and current debates about military doctrines.

But for several reasons, Vietnam vanguard, the history of the 1966 tour of the 5th Battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment (5RAR) in Vietnam, edited by Ron Boxall and Robert O’Neill, deserves more attention than most works of its kind.

Part of the explanation can be seen in the subtitle: The 5th Battalion’s approach to counter-insurgency, 1966. The first Australian infantry battalion to be committed to Vietnam in 1965, 1RAR, was inserted into the American 173rd Airborne Brigade. Theirs was not a happy experience. The Australians were not impressed by the American way of war, with its emphasis on massive firepower and measuring success by body counts and kill ratios. Many thought that the tactics developed by Australian and British forces in the Malayan Emergency and the Indonesian Confrontation were better suited to the Vietnam campaign, and less likely to lead to a politically unacceptable casualty rate.

The Australian government’s decision to increase the commitment to a task force of two (later three) battalions and associated units was based partly on the desire to fight with greater autonomy in a designated area. The first two battalions to be sent to Phuoc Tuy province were 5RAR and 6RAR. Without, it would seem, much guidance from higher authorities, each battalion largely fought its own war. The most famous Australian engagement of the entire war, the Battle of Long Tan, was fought principally by 6RAR, and only appears on the margins of this account.

The commanding officer of 5RAR, Lieutenant Colonel John Warr, clearly recognised that he and his men faced an intellectual as much as a military challenge. This book tells the story, not just of 5RAR’s operations, but also of the battalion’s efforts to develop an operational concept appropriate for their environment. Many of the regular soldiers in the battalion had served in Malaya and Borneo, but Warr’s own military experience was in Korea.

As intelligence officer, Warr appointed a 30-year-old Duntroon graduate, Captain Robert O’Neill, better known to readers of The Strategist as Professor O’Neill, whose curriculum vitae as military historian, strategist and institution builder would occupy the rest of this post. When 5RAR began its tour, O’Neill had recently completed his Oxford doctoral thesis, published during the tour as The German Army and the Nazi Party 1933–1939.

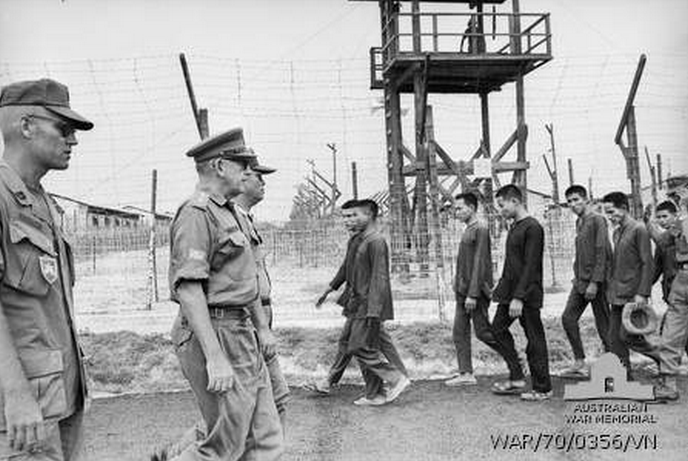

All contributors to the book emphasise Warr’s leadership in bringing together this range of skills and experience to define an operational concept appropriate for Phuoc Tuy in 1966. The result was a distinctive approach, with a strong emphasis on cordon-and-search operations. This was all about operating quietly, not worrying about body counts or kill ratios but concentrating on identifying and removing the opponents of the government, with minimal disruption to village life.

Vietnam vanguard thus provides a ‘bottom-up’ perspective on the development of a particular approach to counterinsurgency operations. It makes a noteworthy contribution to wider debates on military doctrine, such as those in which the US Army engaged before, during and after the promulgation of its 2006 field manual on counterinsurgency, particularly associated with General David Petraeus.

Some of the material will be familiar to readers of Vietnam task, the 1968 book based on O’Neill’s letters to his wife, as well as War, strategy and history, the 2016 festschrift in O’Neill’s honour, and the relevant volume of the official history.

The passage of time since the 1966 tour allows this book to benefit not only from further reflection but also from contributions from military historians with expertise in relevant fields. David Horner contributes a chapter on the decisions to allocate the task force to Phuoc Tuy province and, more controversially, to base it at Nui Dat. Ernest Chamberlain, an army linguist, draws on his extensive knowledge of the histories of the Viet Cong units against whom the Australians fought. There are also useful contributions from those who served in artillery and army aviation units that supported 5RAR.

To say this book deserves a place today on the reading lists of Australian officer cadets and others interested in military doctrine is not to endorse simplistic arguments along the lines of ‘Australian counterinsurgency good, American attrition warfare bad’, or ‘If the Americans had adopted the tactics the British and Australians used in Malaya, they would have won in Vietnam.’

The Vietnam War was long and complex: what worked well in Phuoc Tuy in 1966 would not necessarily have done so in other parts of Vietnam, or even in Phuoc Tuy in later years. But Vietnam vanguard melds personal experience and half a century of historical research and reflection to produce something significantly more than just another unit history.