Beijing and Washington take opposite tacks in attempting to avoid economic crisis

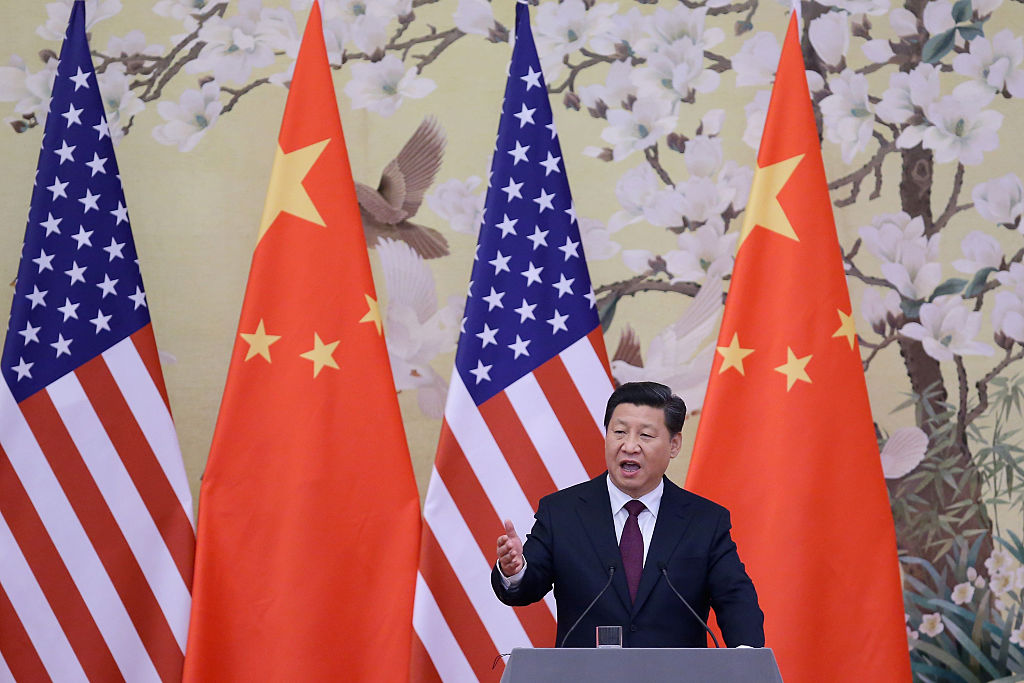

Xi Jinping and Joe Biden both face major political events in the closing months of this year and want economic conditions to be as favourable as possible, but the two have taken opposite tacks on the desirable course of interest rates.

For the US president, who confronts elections in November that may shatter the Democrats’ already fragile hold on Congress, the biggest risk is rising prices for consumer essentials. As a result, Biden sees the case for higher interest rates.

‘The critical job of making sure that the elevated prices don’t become entrenched rests with the Federal Reserve,’ Biden said in his first press conference of the year.

‘Given the strength of our economy and recent price increases, it’s appropriate, as Fed Chairman [Jerome] Powell has indicated, to recalibrate the support that is now necessary,’ he said.

Xi needs to smooth the path for the National People’s Congress, to be held in October or November, which is expected to endorse his leadership for an unprecedented third five-year term.

He wants the Fed and the European Central Bank to continue the easy monetary policy that has added stimulus to the global economy during the Covid-19 pandemic.

‘If major economies slam on the brakes or take a U-turn in their monetary policies, there would be serious negative spillovers. They would present challenges to global economic and financial stability, and developing countries would bear the brunt of it,’ Xi told the Davos conference in a video address on 17 January.

Markets are tipping the Fed to start hiking rates in March, with some economists calling for a 0.5% increase to show the central bank’s determination to control inflation.

If the US concern is that its economy is overheating under the pressure of strong consumer demand and supply-chain constraints, China’s preoccupation is the opposite. Chinese authorities are worried that consumer demand is too weak already and vulnerable both to further downturns in the troubled property sector and to the effects of more Covid lockdowns.

While China’s fourth-quarter GDP figures appeared to show a healthy recovery from the depressed results of 2020, growth was driven mainly by exports, which were up by a massive 30% over the year. Retail sales in December were only 1.7% ahead of the previous year, while sales over 2021 were up only 3.9% from pre-Covid levels in 2019.

China is relying on the demand from the West—principally the US—to support its growth, rather than on the spending of its own massive population.

The World Bank’s latest review of the global outlook underlined the risk that China’s real-estate crisis has the potential to trigger financial turbulence that would spill across much of the developing world. The bank highlights the heavy debts carried by China’s property developers.

‘The risks and potential costs of contagion from a sharp deleveraging of large firms, especially in the real estate sector—with combined onshore and offshore liabilities amounting to almost 30% of GDP and strong linkages to various parts of the economy—far exceed any potential damage from the collapse of a typical large industrial company,’ it says.

The review notes that corporate bonds issued by Chinese property developers are already trading at distressed prices, indicating that financial markets are expecting widespread defaults.

The property sector accounts for around a quarter of China’s investment, is an important source of income for both local governments and households, and is the destination for 40–50% of bank loans.

China’s authorities are responding to the risks in the economic outlook in their classic fashion. The State Council has announced plans to increase the size of the high-speed rail network from 38,000 to 50,000 kilometres by 2025, with a commitment to focus on construction that could begin this year. The central bank has cut reserve requirements for banks, while state-owned enterprises are being told to take on the completion of troubled private-sector housing developments.

But the government has not yet relaxed the tougher borrowing guidelines for property developers that pushed China’s second largest, Evergrande, into a financial crisis that’s spreading across the country’s property sector.

In his Davos speech, Xi defended the ‘common prosperity’ strategy that has been used to justify regulatory crackdowns on a range of private-sector industries, saying it aimed to ensure ‘everyone will get a fair share from development, and development gains benefit all our people in a more substantial and equitable way’.

The danger for China and for Xi is that the preponderant role of the state will not be able to tame a rolling debt crisis that has a circular logic of its own, with the loss of confidence in property developers resulting in falling property prices that further undermine the security of their already tenuous debts.

The Chinese authorities’ continuing drive to achieve zero Covid is a further risk to the country’s economic performance this year. Success so far in suppressing Covid has been hailed by Xi as evidence of the superiority of the Chinese form of government, but it has not been cost-free, with severe lockdowns imposed wherever cases occur. The virulence of the Omicron strain of the virus is testing the sustainability of the strategy.

Xi has reason to see rising US interest rates as a threat to the world economy and to developing nations in particular. Higher US rates would bring a tidal movement of capital out of the rest of the world and into the United States. Developing nations with currencies tied to the US dollar would have no option but to raise their own interest rates, regardless of their domestic circumstances. Rolling over US dollar debts would become difficult, raising the danger of defaults.

Even China, which ostensibly manages capital flows into and out of the country, would face pressure to devalue its currency, raising the local burden of its US dollar debts.

Much depends on how far the Fed goes. While there’s agreement that the US no longer needs the stimulation of 0% rates and massive central-bank purchases of government bonds, many still argue that high inflation (7% in the year to December) is a result of supply-chain problems rather than excessive demand. This means interest rate increases would have little effect.

The nightmare result for Biden would be rising interest rates and rising prices. Around the world, excessively tight monetary policy is a known cause of recession—Australia’s 1990 and 1982 recessions come to mind. Both Biden and Xi will be hoping this scenario doesn’t come to pass.