US-China cooperation remains possible

When US Secretary of State Antony Blinken visited Beijing last month in an effort to stabilise relations with China, many of the issues that he discussed with Chinese President Xi Jinping were highly contentious.

For example, Blinken warned China against providing materials and technology to aid Russia in its war against Ukraine, and he objected to China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea and harassment of the Philippines, a US ally. Other disputes concerned interpretations of the United States’ one-China policy towards Taiwan, and US trade and export controls on the flow of technology to China.

I was visiting Beijing around the same time as the chair of a Sino-American Track II dialogue, where citizens who are in communication with their respective governments can meet and speak for themselves. Because such talks are unofficial and disavowable, they can sometimes be more candid.

That was certainly the case this time, when a delegation from the Aspen Strategy Group met with a group assembled by the influential Central Party School in Beijing; it was the sixth such meeting between the two institutions over the past decade.

As one would expect, the Americans reinforced Blinken’s message on the contentious issues, and the Chinese repeated their own government’s positions. One retired Chinese general warned, ‘Taiwan is the core of our core issues.’

Things became more interesting, however, when the group turned to explore possible areas of cooperation. The change in US policy from engagement with China to a strategy of great-power competition does not preclude cooperation in some areas. In framing the discussion, we used the analogy of a soccer game: two teams battle fiercely, but they kick the ball, rather than the other players, and everyone is expected to stay within the white lines.

Switching metaphors, some Chinese did worry that the American emphasis on establishing guard rails was like putting seat belts in a car that encouraged speeding; but most agreed that avoiding a crash was the primary objective. To that end, we identified seven areas of potential cooperation.

The first and most obvious was climate change, which threatens both countries. Although China is continuing to build coal-fired power plants, it is rapidly adding renewable sources of energy, and it claims it will reach peak carbon dioxide emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060. We urged a more rapid timetable and scientific exchanges to that end.

The second issue was global public health. Scientists say the next pandemic is not a question of if, but when. Both governments handled Covid-19 badly, and millions died as a result. But rather than argue over whom to blame, we suggested studying how our scientific cooperation helped slow SARS in 2003 and Ebola in 2014, and how we could apply those lessons in the future.

On nuclear weapons, the Chinese defended their rapid build-up on the grounds that intercontinental ballistic missiles are more accurate and that the vulnerability of submarines may someday jeopardise their capability to strike back if they are struck first. They repeated their familiar objection to adopting arms-control limitations before their arsenal matches those of the US and Russia. But they expressed a willingness to discuss nuclear doctrine, concepts, and strategic stability, as well as non-proliferation and such difficult cases as North Korea and Iran—two areas where America and China have cooperated in the past.

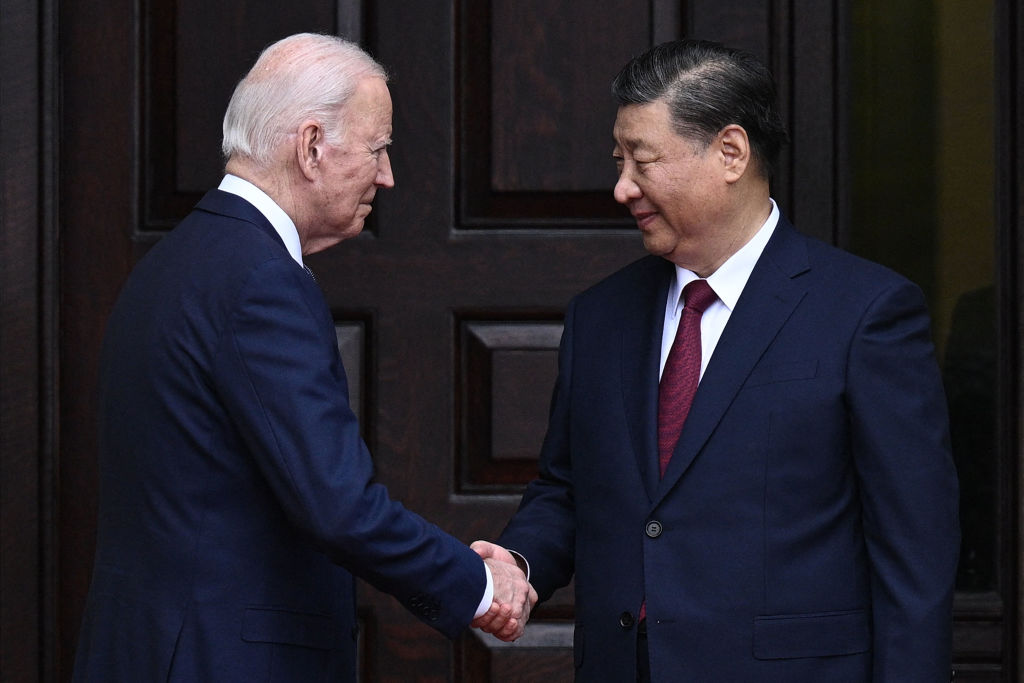

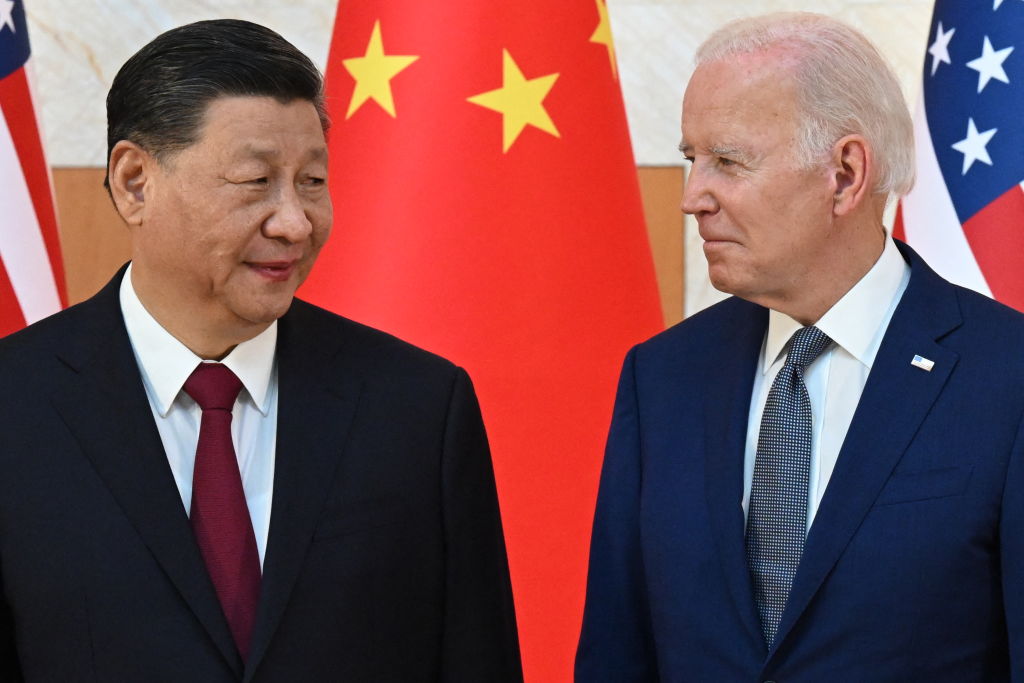

The fourth issue was artificial intelligence. In San Francisco in November, Xi and US President Joe Biden agreed to begin talks about artificial-intelligence safety—though their governments have not yet made much progress. Our group agreed that the issue also calls for private talks behind closed doors, particularly about the technology’s military applications. As one retired Chinese general put it, arms control is unlikely, but there is a big opportunity to work towards a mutual understanding of concepts and doctrine, and what it means to maintain human control.

On economics, both sides agreed that bilateral trade is mutually beneficial, but the Chinese complained about US export controls on advanced semiconductors. While the US justifies its policy on security grounds, the Chinese see it as a measure designed to constrain their country’s economic growth. Since US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan has described the US approach as building ‘a high fence around a small yard’, we pointed out that it affects only a small portion of our total trade in chips.

The topic of Chinese overcapacity in industrial production, which is fuelled by subsidies, was more difficult. China’s economic growth has slowed, and rather than taking steps to bolster its domestic consumption, it is trying to export its way out of its current problems, as it has done in the past. We pointed out that the world has changed since the China shock at the beginning of the century.

But rather than countenance a decoupling that would be bad for both sides, we agreed to divide economic issues into three buckets. At one end were security issues, where we would agree to disagree. At the other end was the normal trade in goods and services, where we would follow international trade rules. And in the middle, where questions of subsidies and overcapacity arise, we would negotiate issues case by case.

Our final topic concerned people-to-people contacts, which were badly damaged by three years of Covid-19 restrictions and deteriorating political relations. Fewer than 1000 American students are studying in China at present, whereas some 289,000 Chinese are studying at US universities (though that figure has fallen by nearly one-quarter from its peak). Journalists are facing greater visa restrictions in China, and academics and scientists on both sides report more hassling by immigration officials. None of this helps restore a sense of mutual understanding.

In this period of great-power competition between the US and China, we should not expect a return to the strategy of engagement that marked the beginning of this century. But it is in both countries’ interests to avoid conflict, and to identify areas for cooperation when and where we can.