There are good reasons why the best science and speculative fiction ranks high on the reading lists of many military scholars and leaders. Done well, speculative military fiction projects thoughtfully beyond the here and now, and renders real operational and strategic concepts in terms of plausible future technologies. This encourages us to think outside the box about our doctrine and our operational assumptions.

The Strategist is publishing two pieces by Jeffrey Becker, leading futurist for the US military, as prime examples of this kind of fiction. Today’s piece, ‘Aces-high frontier’, was first published in January 2019 in The Strategy Bridge. We are republishing it today with kind permission because many of its speculations have been vindicated by real events in Ukraine and elsewhere, showing the foresight that such fiction can achieve. Set in 2053, it discusses ideas such as a ‘kill mesh’, anticipating the lessons learned by Russian forces about combined arms and the role of the private sector, with even a nod to Elon Musk, to give just a couple of examples.

The second piece, to be published in coming months, is new. It examines the importance of rocket forces, advanced space capabilities and, most importantly, adaptation and innovation of people to win the fight on earth. When we look back at these piece of fiction in a few years’ time, how much will be reality, or on its way to becoming reality?

Kill mesh

You expect an electric crackle, the deep whine of machinery, a bolt of red across a planetary foreground, the roar of rocket engines. Wrong. When the US Space Force is in action, it really couldn’t be less cinematic. Anti-visual even.

Yes, the earth is still an astonishing sight from our perch at the earth–moon L4 Lagrange point, but battle itself is rather anticlimactic. No explosions. No starfighters careening this way and that.

The fight I manage (and ‘manage’ in this case is a term I use loosely) unfolds at inhuman speeds. Warfare in 2053 stretches over most of the planet. Thrusts, counters, feints all flash by in the millions over milliseconds. Remorseless AIs manoeuvre electrons, photons, code and data to blind, spoof, confuse, glitch and burn up microchips, radars and anything tied to a computer chip, radar or sensor.

Someone plastered a bright red sticker with an arrow labelled ‘Pointy End’ next to the heads-up display as a joke. How can anything in a 10,000-ton tin can 24,000 miles up be at the pointy end of anything?

But what happens here is very much the cutting blade of US military power worldwide.

‘Admiral Lane,’ ACES called out from my display. ‘Bithammer engagement appears to be successful.’

ACES is the call sign of the L4 station’s global integration AI. The joint force has several joint AIs in action around the world; ACES is at the core of L4 station’s mission and the real secret sauce for US Space Force operations up here.

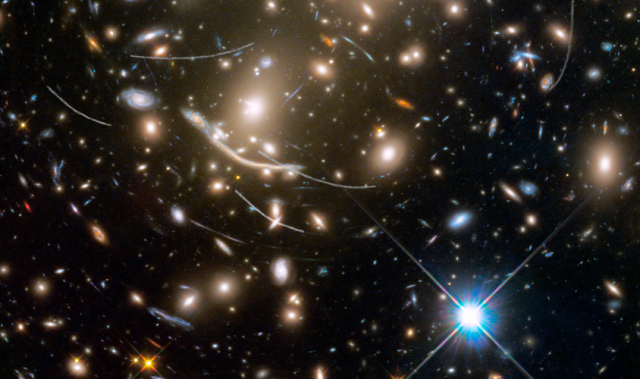

The main job of the L4 station is to protect and feed ACES as it sifts through the trillions of bits collected from sensors, radar returns, emitters and data brought back from cyber-scout AIs. Few movements of military equipment happen planetside without L4 observing and understanding. ACES constantly assesses the military environment and manoeuvres space force assets and tens of thousands of robotic and human land, space and air enablers into place.

ACES can also direct an array of laser, electronic-warfare and cyber-assault capabilities from orbit. Most can reach targets from the earth’s surface to geosynchronous orbit. Primarily consisting of Constellation-class and Viper-class satellites, ACES works to cover and protect every joint force movement, munition, base and facility with electromagnetic and cyber fire. In this kill mesh, machine-age weapons like tanks, surface ships and fighter aircraft are not useful on their own.

Although space force operations are not very visually spectacular, the results of engaging from space are really quite effective.

Satisfying.

Usually, radars burn up, platforms go dumb, 3-D printers trying to construct or rebuild bricked components make defective replacements. Things just don’t work as the space force amplifies and weaponises Clausewitz’s fog and friction.

ACES collects full-motion, real-time hyperspectral data at one-inch resolution from thousands of orbiting platforms. Space force radars and lasers seek out sensors and emitters, while ACES catalogues and probes interesting targets with mobile code. ACES collects this information and builds a synthetic model of the world to understand meaning and implications.

‘Request authority to execute interdiction mode 4,’ ACES asked through my immersive display.

‘Granted.’ This command provides the AI with the parameters to coordinate global cyber, electromagnetic and directed-energy strikes against groups of the People Liberation Army’s air, maritime and ground mobile orbital interdiction lasers.

These mobile lasers are enforcing a self-declared orbital defence identification zone, or ODIZ, stretching from 60 miles up to geostationary orbit. China currently demands that satellite operators pay a fee to transit over its territory and comply with restrictions on sensing or emitting while inside the ODIZ.

‘Employing 263 femtosecond laser pulses, from six Viper platforms.’

Each of these pulses would send a cascade of gamma radiation through its target. Although the primary effect is to damage the adaptive optics actuators, ACES is manoeuvring viruses through the temporarily blinded firewall, allowing mobile lock code to infiltrate the system and beaconing the system for follow-on targeting.

‘Continuing engagements.’

ACES scanned the surface for other systems attempting to enforce the ODIZ. ACES sums up thousands of scans, cyber reconnaissance actions, and the results of correlation analysis on my screen. Streaks of green began to appear within the red orbital zone above China denoting corridors clear of the laser and electronic-warfare threat from the ground.

Decades of deep neural net correlation analysis and millions of simulations mean we trust that ACES can confound, disrupt and destroy when we need it to. And we need it to. The president ordered ACES into action to maintain orbital freedom of navigation over China despite the ODIZ.

Operating from US Space Force Base L4

Why build a military facility at L4?

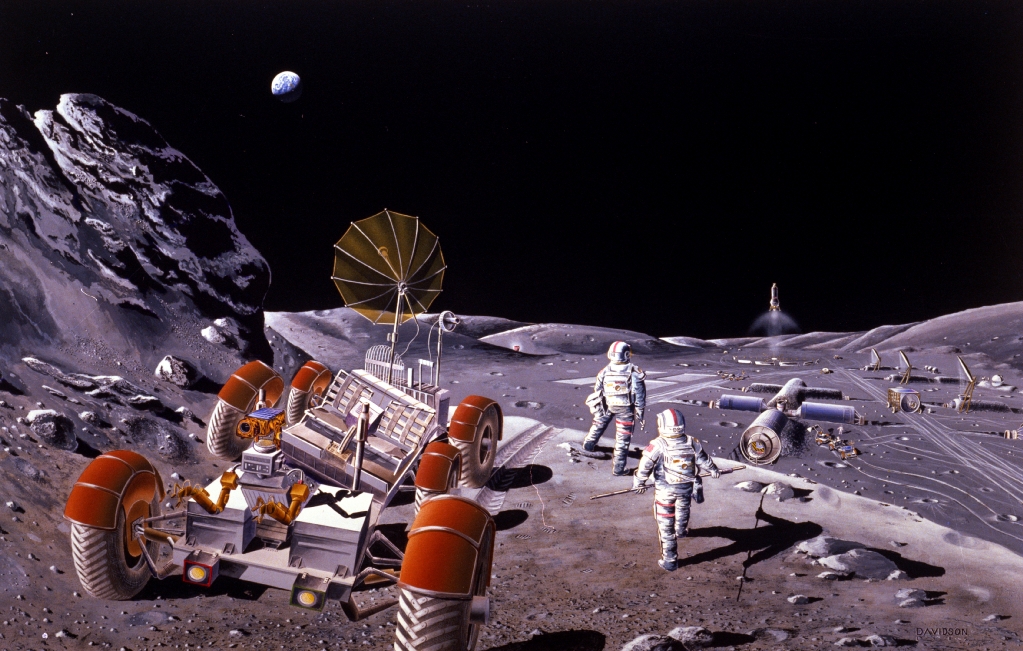

The oldest rule in the book is to fight from the high ground. And from L4 everything is effectively downhill. Better yet, objects put here tend to stay here. It’s also why private companies gently and carefully moved a pair of half-mile-long asteroids to this specific spot in orbit in the late 2030s.

The asteroids, Plymouth and Williamsburg, are brightly visible from the station’s observation deck. Plymouth is a chunk of raw metal and home to many lucrative mining and manufacturing facilities. The ice of Williamsburg is even more valuable, supporting a thriving satellite refuelling business, shuttling hydrogen and oxygen to users far more cheaply than bringing it up from earth.

Right now, only Five Eyes partner nations mine here. Many other nations don’t believe we should be able to capture and use these for exclusive commercial purposes. Part of the L4 mission is to keep an eye on these commercial activities, as US national strategy directs the space force to protect scientific and economic access to outer space for the US and its allies and partners around the world.

Suddenly, my visual display froze and the station shuddered hard, visibly accelerating towards Plymouth. Much closer than I would like.

ACES came up on the headset again. ‘Sir, several temperature spikes are reading across the station. External communications shut down, and pointing and tracking temporarily disrupted.’

‘What’s the cause?’

‘I assess that we’ve been struck by several bursts of a high-energy laser. The targets suggest that the attack is intended to interdict our counter-ODIZ campaign. In fact, I’ve lost control over the Vipers currently operating in the China–LEO theater. Working to restore.’

The lights throughout the station flashed momentarily. Air vents not blowing. Not good.

‘ACES, where is it coming from? I thought you had the draw on any DE in range of the station?’

‘The geometry of the attack and the energy flux indicate a laser with a capacity of a petawatt or greater striking from the southern polar region of the lunar surface.’

How we fight

The US Space Force was really a response to the Chinese, who since the 2020s had increasingly knitted space, cyber and electronic-warfare capabilities in its innocuously named Strategic Support Force. China recognised the need to be vigilant, active and dominant in information confrontation in all its forms.

Indeed, as far back as 2005, Chinese writers noted that ‘before the troops and horses move, the satellites are already moving’. They understood very early that without space dominance, information dominance would not be possible. Without information dominance, operations in the air, sea and land would fail. Thus, in the Chinese mind, space would inevitably be a battleground.

The Chinese and the Russians appeared to be well in advance of us on the conceptual importance of the fusion of information, space, cyber and the electromagnetic spectrum. What set the US Space Force in a class by itself was its inexplicable—almost magical—lead in space lift.

‘Thank you, Elon Musk,’ I thought, picturing Musk’s cherry-red first-run Tesla at the entrance to his compound on Mars.

EBFR rockets and space vehicles (SpaceX for ‘Even Bigger Falcon Rocket’) allowed the US and its partners and allies to build a thriving commercial space industry. Like the historic Model T, DC-3 or Nimitz-class carrier, EBFR is a tangible and easily recognised symbol of American technology and power.

The Chinese still don’t have anything as big, cheap and capable as EBFR. The Russians are still dumping their used rockets at sea.

We use dozens of EBFRs to throw thousands of mass-produced satellites in orbit almost at will. Our global command-and-control network funnels data to the L4 station and knits it together into a real-time, multispectral Google Earth. ACES thinks through this tsunami of data, simulates and emulates it, and provides near-real-time, in-depth analysis of activities and probabilities of all military infrastructure on the planet. We can even rewind.

The big dark

Because of our overwhelming competitive advantages in space, the Chinese went a different way—focusing instead on lasers, hypersonics and quantum-based encryption, and hiding their goals and objectives.

We didn’t see this direct attack on L4 coming. We didn’t see the ODIZ declaration coming.

‘ACES, what do you know about the Big Dark?’

‘Although we can still see what’s going on physically within China and around the world, I calculate they’ve been able to pull together quantum computers, communications and optical elements into an end-to-end secure network. Although I can sometimes detect the links between different nodes, when I attempt to decrypt the messages, they disappear.’

‘Meaning?’

‘I suspect they’ve used my ignorance to plan and execute this ODIZ enforcement effort. Pushing their airspace and keeping us behind Plymouth means I can’t observe China from space. That unlocks their ballistic and hypersonic systems as well as air, sea and land assets to operate without interference.’

I thought for a moment. ‘We’re blind and our forces on earth are vulnerable to attack.’

Operation AlphaGo

‘Sir, the shuddering you felt was me moving the station behind Plymouth. This puts the asteroid between us and the moon. The L4 station is very well protected here. No laser can penetrate a rock of this size. However, we are pinned down and I cannot integrate counter-ODIZ operations. I anticipate large-scale terrestrial movement of their forces soon.’

‘What is going on with China on the moon? I mean, beyond the fact that they’ve managed to install a working battle laser without us noticing.’

The 10-person research station at the moon’s south pole has always been something of an enigma. Strangely, over the past decade they worked to string kilometres of wire in a radio-astronomical instrument conveniently spanning the moon’s only accessible sources of water.

The Chinese recognise how touchy we are about incursions on our old Apollo sites. Like us, they refer to the instrument as the common heritage of mankind that should not be disturbed. This put most of the moon’s water under their direct control. It also means they have the fuel to power a station capable of operating a laser of that size.

ACES thought for an interminable moment. (I find long pauses from AI very disturbing.)

‘AlphaGo versus Sedol, game 2, move 37,’ came back over my headset.

Sometimes ACES free-associates things. Humans often take time to catch up with the mental connections AIs can make. However, the reference to Lee Sedol’s epic 2016 Go match with AlphaGo was clear. The Aerospace War College’s ‘Intro to AI’ class (taught by an AI, of course) uses the game as an example of how AI can demonstrate extraordinary, superhuman foresight.

Go was thought to be too complex for AIs to compete with world-class human players. AlphaGo placed a black stone in a position never seen in Go’s 2,000-year history. Sedol left the table in shock at the long-term implications of the move and soon resigned the game.

‘So, while we’ve been focused on earth, China managed to put a working weapon on our spaceward flank?’ I asked.

‘Yes.’ ACES replied. ‘My working hypothesis is that the base has built a laser capable of interdicting us in GEO and L4. Maybe even to earth itself. In effect, this laser is a black-piece move so far off the board that it appears irrelevant, but is really a potentially dominant strategic gambit.’

‘The Chinese are playing a game of position against our campaign of manoeuvre and cyber-electromagnetic attrition?’

‘Yes,’ ACES replied. ‘I’ll need some assistance setting new parameters, Admiral.’

ACES fit together a number of movements into a potential Chinese theory of victory. The most likely scenario playing out on my strategic display—now showing the broader earth–moon system, key orbits and positions, as well as how a struggle for control might unfold. A bright red point radiated out from the moon’s south pole, rays beginning to isolate the L4 station and collapsing our ability to use orbital space and thus to control the information confrontation on earth.

ACES began to put together options, already communicating designs for a fast-moving weapon to attack the moon station. The vehicle, built out of an entirely new ring and stack assembly, would be shaped and moulded from Plymouth’s metal. Looking like an alien spider web of tangled metal, the assembly would distribute high-G loads from three connected EBFR orbital segments and a formation of observation, Viper and Constellation sats. The spider web would allow the EBFRs to deliver a fleet of combat sats towards the lunar base at high speed.

But first, the spider web would be connected to a rough slab of ice cut from Williamsburg. The ice slab would shield the satellites and EBFRs from the attacking lunar laser. After departing earth orbit, the jury-rigged vehicle would swing 35 miles above the lunar south pole. At perigee, three observation sats would detach from the spider web, emerging from behind the slab in different directions and mapping the Chinese lunar base below. They would be destroyed quickly, but ACES could use the data to construct a model of the base, ejecting and manoeuvring nine Viper and Constellation sats from behind the slab seconds later, hitting as much of the base’s critical infrastructure as possible.

Two days later, after swinging through a high, looping orbit, the remainder of the stack, including the spider web and ice shield, would crash into the base, making an immense crater and putting the laser (and probably the whole station) out of business for good.

The president flashed up on the display. ‘Admiral Lane. I understand you are under attack. What do you advise?’

‘ACES, will you please show the president the concept?’