Seeking to undermine democracy and partnerships

How the CCP is influencing the Pacific islands information environment

What’s the problem?

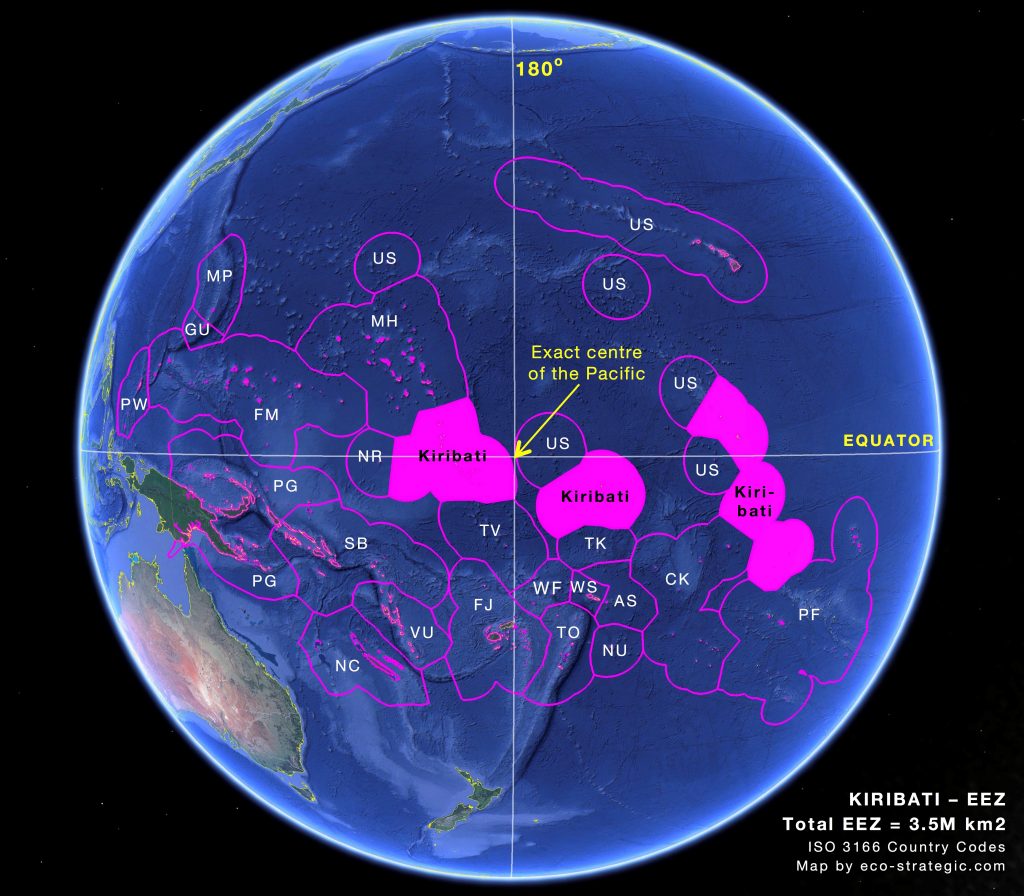

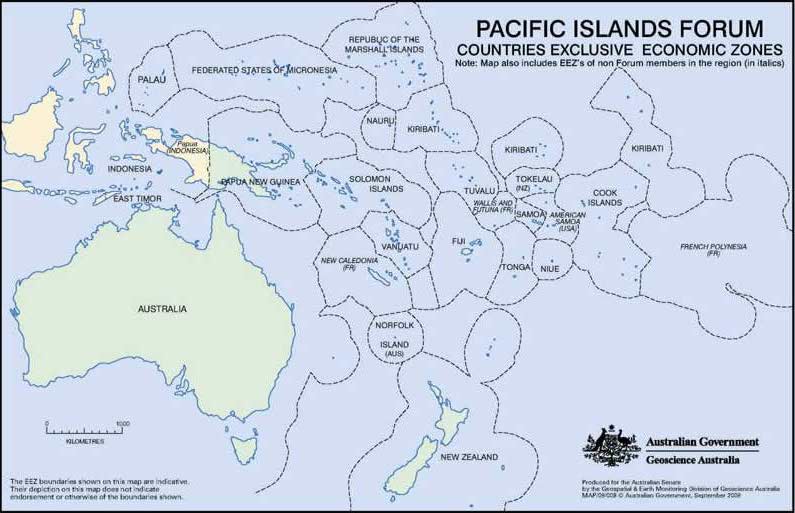

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is conducting coordinated information operations in Pacific island countries (PICs). Those operations are designed to influence political elites, public discourse and political sentiment regarding existing partnerships with Western democracies. Our research shows how the CCP frequently seeks to capitalise on regional events, announcements and engagements to push its own narratives, many of which are aimed at undermining some of the region’s key partnerships.

This report examines three significant events and developments:

- the establishment of AUKUS in 2021

- the CCP’s recent efforts to sign a region-wide security agreement

- the 2022 Pacific Islands Forum held in Fiji.

This research, including these three case studies, shows how the CCP uses tailored, reactive messaging in response to regional events and analyses the effectiveness of that messaging in shifting public discourse online.

This report also highlights a series of information channels used by the CCP to push narratives in support of the party’s regional objectives in the Pacific. Those information channels include Chinese state media, CCP publications and statements in local media, and publications by local journalists connected to CCP-linked groups.1

There’s growing recognition of the information operations and misinformation and disinformation being spread globally under the CCP’s directives. Although the CCP’s information operations have had little demonstrated effectiveness in shifting online public sentiment in the case studies examined in this report, they’ve previously proven to be effective in influencing public discourse and political elites in the Pacific.2 Analysing the long-term impact of these operations, so that informed policy decisions can be made by governments and by social media platforms, requires greater measurement and understanding of current operations and local sentiment.

What’s the solution?

The CCP’s presence in the information environment is expanding across the Pacific through online and social media platforms, local and China-based training opportunities, and greater television and short-wave radio programming.3 However, the impact of this growing footprint in the information environment remains largely unexplored and unaddressed by policymakers in the Pacific and in the partner countries that are frequently targeted by the CCP’s information operations.

Pacific partners, including Australia, the US, New Zealand, Japan, the UK and the European Union, need to enhance partnerships with Pacific island media outlets and online news forum managers in order to build a stronger, more resilient media industry that will be less vulnerable to disinformation and pressures exerted by the CCP. This includes further assistance in hiring, training and retaining high-quality professional journalists and media executives and providing financial support without conditions to uphold media freedom in the Pacific. Training should be offered to support online discussion forum managers sharing news content to counter the spread of disinformation and misinformation in public online groups. The data analysis in this report highlights a need for policymakers and platforms to invest more resources in countering CCP information operations in Melanesia, which is shown to have greater susceptibility to those operations.

As part of their targeted training package, Pacific island media and security institutions, such as the Pacific Fusion Centre, should receive further training on identifying disinformation and coordinated information operations to help build media resiliency. For that training to be effective, governments should fund additional research into the actors and activities affecting the Pacific islands information environment, including climate-change and election disinformation and misinformation, and foreign influence activities.

Information sharing among PICs’ media institutions would build greater regional understanding of CCP influence in the information environment and other online harms and malign activity. ASPI has also previously proposed that an Indo-Pacific hybrid threats centre would help regional governments, businesses and civil society better understand and counter those threats.4

Pacific partners, particularly Australia and the US, need to be more effective and transparent in communicating how aid delivered to the region is benefiting PICs and building people-to-people links. Locally based diplomats need to work more closely with Pacific media to contextualise information from press releases and statements and give PIC audiences a better understanding of the benefits delivered by Western governments’ assistance. This includes greater transparency on the provision of aid in the region. Doing so will debunk some of the CCP’s narratives regarding Western support and legitimacy in the region.

- A number of local journalists and media contributors have connections to CCP-linked entities, such as Pacific friendship associations. The connections between friendship associations and CCP influence are described in Anne-Marie Brady, ‘Australia and its partners must bring the Pacific into the fold on Chinese interference’, The Strategist, 21 April 2022. ↩︎

- Blake Johnson, Miah Hammond-Errey, Daria Impiombato, Albert Zhang, Joshua Dunne, Suppressing the truth and spreading lies: how the CCP is influencing Solomon Islands’ information environment, ASPI, Canberra. ↩︎

- Richard Herr, Chinese influence in the Pacific islands: the yin and yang of soft power, ASPI, Canberra, 30 April 2019, online; Denghua Zhang, Amanda Watson, ‘China’s media strategy in the Pacific’, In Brief 2020/29, Department of Pacific Affairs, Australian National University, 26 March 2021, online; Dorothy Wickham, ‘The lesson from my trip to China? Solomon Islands not ready to deal with the giant’, The Guardian, 23 December 2019. ↩︎

- Lesley Seebeck, Emily Williams, Jacob Wallis, Countering the Hydra: a proposal for an Indo-Pacific hybrid threat centre, ASPI, Canberra, 7 June 2022. ↩︎