‘How did you go bankrupt?’

‘Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.’

― Ernest Hemingway, The sun also rises

As with bankruptcy so with military defeat. What appears to be a long, painful grind can quickly turn into a rout. A supposedly resilient and well-equipped army can break and look for means of escape. This is not unusual in war. We saw it happen with the Afghan Army in the summer of 2021.

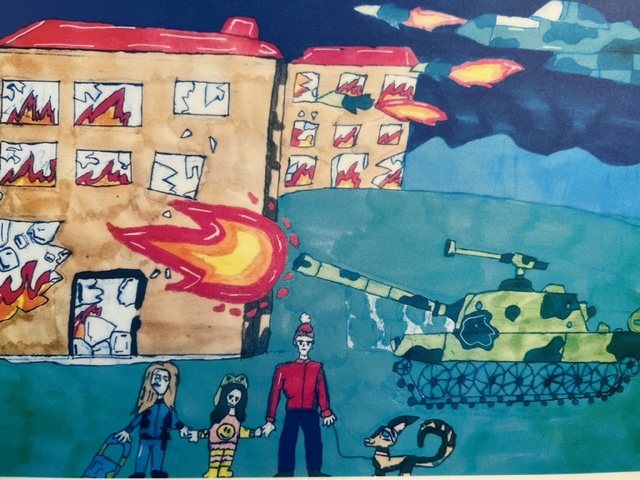

For the past few days we have been witnessing a remarkable Ukrainian offensive in Kharkiv. We have the spectacle of a bedraggled army in retreat—remnants of a smashed-up convoy, abandoned vehicles, positions left in a hurry, with scattered kit and uneaten food, miserable prisoners, and local people cheering on the Ukrainian forces as they drive through their villages. The speed of advance has been impressive, as tens of square kilometres turn into hundreds and then thousands, and from a handful of villages and towns liberated to dozens. Even as I have been writing this post paragraphs keep on getting overtaken by events.

It would of course be premature to pronounce a complete Ukrainian victory in the war because of one successful and unexpected breakthrough. But what has happened over the past few days is of historic importance. This offensive has overturned much of what was confidently assumed about the course of the war. It serves as a reminder that just because the front lines appear static it does not mean that they will stay that way, and that morale and motivation drain away from armies facing defeat, especially when the troops are uncertain about the cause for which they are fighting and have lost confidence in their officers. Who wants to be a martyr when the war is already lost?

Ukrainian objectives

The Kharkiv offensive has been described as opportunistic. This is because the Ukrainian high command appears to have decided to take advantage of Russia moving substantial forces towards Kherson to deal with the much-advertised attack there by opening up a new offensive against areas that had been left with weaker defences. According to an alternative explanation, this was not opportunistic but always intended. The Russians were suckered by Ukraine’s regular talk of this coming Kherson offensive into diverting troops, even though Kharkiv was always the real objective. It would, however, be unwise to assume that the Kherson offensive is of only secondary relevance: southern Ukraine remains of great strategic importance for the Ukrainian economy, the links to the Black Sea, and the connection to Crimea. The offensive there has not been halted for the sake of Kharkiv and is also still making progress.

In practice, as with all good strategists, the Ukrainian commanders probably prepared for a range of contingencies. Their choices depended on what the Russian did. Once they saw the extent of the Russian troop movements, and the developing vulnerability this created, then the plan for Kharkiv will have firmed up in their minds. I also suspect that they wanted to make sure that the Kherson offensive was well established before risking opening up another front and that this governed the timing.

What we can be sure of is that the Kharkiv offensive was not impulsive. It required careful preparation, including getting troops and their equipment into position without their intentions becoming too obvious. A sequence of moves has unfolded over the last few days designed to shock and disorient Russian forces, breaking through thin lines of defence, avoiding distractions by bypassing Russian positions that were in no position to interfere with their movement, and threatening them, and the rest of the Russian force in the region, with being cut off from their sources of supply and reinforcement, and also means of escape. The aim was not simply to grab territory and inflict blows on Russian forces, though that has been done. One aim was to get to Kupyansk, a city of 27,000 inhabitants, a major transportation hub for both road and rail. The other was to take Izyum (45,000 inhabitants), with its substantial garrison and command centre.

When the operation started, the first target was the city Balakliya (over 25,000 inhabitants), which was encircled before the Russian defenders were pushed out. From there the Ukrainians drove forward, achieving a pincer movement by also pushing forward to the Oskil river, south of Kupyansk. To prevent reinforcements coming in, Ukraine damaged the bridge across the Oskil to Kupyansk. On Friday, another offensive line opened up with an attack on Russian positions in Lyman (over 20,000 inhabitants), which had been taken by the Russians after a fierce battle at the end of May. This opened up the move against Izyum. Reports suggest that both Izyum and Kupyansk have either fallen or are close to falling, with Russians troops in disarray. According to the Ukrainians, hundreds of Russians have already been killed and many captured. Ukrainian sources have described whole units wiped out. It is not clear how many Russian troops may be caught by these manoeuvres—perhaps some 10,000.

There are dangers in offensives where the supply lines get too stretched and forward units lose air defence cover. These are, after all, some of the problems that thwarted the initial Russian offensive last February. Unsurprisingly, the Russian Ministry of Defence has insisted that all will be well and that reinforcements are on the way. Some footage was supplied showing vehicles on the move, although doubts were soon expressed about how real these reinforcements were, what they could do when they arrived, and if they could arrive at all. The main Russian response, as per normal, has been to send random rockets into the city of Kharkiv, killing civilians.

Russian angst

There is one group of Russians who are far from complacent. Russian military bloggers are a patriotic group who are desperate for a Russian victory. Unlike the crude and increasingly risible propagandists, whose instructions are to show that all is well and that any apparent Ukraine advance has already turned into a disastrous failure, the bloggers assess the conflict with a degree of objectivity. They have no desire to praise the regime because they feel badly let down by its ineptitude, by its failure to prepare properly for a major war and also its refusal to put the country on a proper war footing. These nationalists are therefore furious because the best chance to reconnect a wayward Ukraine to Mother Russia has now been lost, and the armed forces are suffering personnel and materiel losses, along with a deep humiliation, from which they will take years to recover.

When it comes to explaining what went wrong, the bloggers consider both the possible underestimation of the enemy as well as overestimation of Russian capabilities. At times it can seem as if the bloggers (in sharp contrast to the propagandists) are talking up the Ukrainians to make their own troops look less bad. They note that Ukrainian forces are benefiting from an inflow of advanced weaponry and have been influenced by Western tactical and operational concepts which they have been applying effectively. Here the bloggers have reported the competence of the Ukrainians in combined arms, synchronising the effects of armour, infantry and artillery, while avoiding unnecessary urban battles and moving with sufficient air defences to make conditions hazardous for Russian airpower.

The bloggers certainly don’t blame their own troops for the current disarray. They are usually portrayed as fighting valiantly. They instead point to weaknesses such as lack of coordination between units, aggravated in the case of Balakliya by part of the defending force being composed of units from Russia’s national guard (Rosgvardia) as well as miserable units from the occupied Donbas, given little choice but to join the army. They note that neither was prepared for this sort of warfare, poorly trained in the proper use of their weapons. Another weakness has been the lack of sufficient artillery and air support, with inadequate intelligence so that, unlike the Ukrainians, the Russians have been unable to call in precise artillery fire.

The limits of intelligence have also been evident in other respects. The local Russian command failed to pick up any signs of the impending assault. The poor performance of airpower, one of the few means available to Russians to disrupt the Ukrainian advance, suggests that it has been effectively neutralised. ‘In general things are really bad’, writes one blogger. ‘There has not been much resistance from our side for the third day already. Our troops abandon not particularly fortified positions and retreat.’

Most importantly, some now consider defeat possible. Few believe that the position in Kharkiv can be recovered. One contemplates catastrophe: ‘Sergei Shoigu [Minister of Defence] and Valery Gerasimov [Chief of the General Staff] are one step away from an unthinkable achievement—the strategic defeat of the RF Armed Forces by a deliberately weaker enemy with almost no aviation, and with their own aviation.’

The notorious Igor Girkin has observed: ’The war in Ukraine will continue until the complete defeat of Russia. We have already lost, the rest is just a matter of time.’

What next?

Russia is losing but it has not yet lost. It still occupies a large chunk of Ukrainian territory and still has substantial military assets in the country. As I have argued regularly, wars can take unexpected turns, as we have just seen. Calamitous miscalculations as well as audacious manoeuvres can transform the character of a conflict. There is always a risk of analyses getting too far ahead, jumping from the current state of affairs to the next and beyond and then asking what happens in purely hypothetical situations. Earlier in the summer there was a tendency to assume that the coming months would be dominated either by more gruelling Russian offensives as in the Donbas or perhaps a stalemate, so that the war could last months or even years. This stalemate philosophy still persists, not least because it is hard to even contemplate such a great military power being humbled.

So while the situation is far more positive for Ukraine, the same cautions about extrapolating too far ahead must apply. Even if Kharkiv is completely liberated there will still be much to do. In the Kherson Oblast the other offensive is also developing and taking shape. This has so far been in the ‘slow grind’ category, though it is picking up pace and more encirclement operations are possible there. The Russians must now be worrying about their position in Donetsk. Unresolved is the extraordinarily dangerous situation at the Zaporizhzhya nuclear power plant. This is an unsustainable situation, one the director-general of the International Atomic Energy Agency has described as ‘precarious’ as the plant’s offsite power has been turned off and it is still being shelled.

The initiative is now firmly with Ukraine. The experience of the last few days will create doubts in the minds of Russian commanders about the reliability and resilience of their troops, and add to the predicaments they already face when working out how to allocate their increasingly scarce resources of manpower, intelligence assets and airpower. Might they risk a repeat of this operational disaster if they move forces to plug one gap only for another to open up? How much more can they expect from their forces, many of whom will now have been fighting for long weeks without respite and without much to show for their efforts? By contrast, there will have been a boost to the morale of even the more beleaguered Ukrainian forces (and, as the Washington Post reports, some of their units have also had a tough time). There may also have been a boost to their capabilities from supplies of equipment and ammunition captured in Kharkiv.

There is now talk of defeat on the Russian side. There was no sense of this in President Vladimir Putin’s insouciant remarks at the Vladivostok economic forum, with Russia’s isolation symbolised by the lack of international presence (Myanmar, Chinese and Armenian representatives turned up). He claimed that nothing had been lost by the war and sovereignty had been gained, as if his desire to intensify autocracy and achieve autarky in the name of self-reliance has been worth the tens of thousands of Russians dead, wounded and taken prisoner, and the years of defence production and economic modernisation up in smoke. His forces might stabilise the situation, at least away from Kharkiv, and provide more breathing space while he hopes Europe’s economic pain leads it to abandon Ukraine. But as I argued in my last post, that is unlikely to happen, and he may now have less time than he thought to find out.

Because of the opacity of Putin’s decision-making and his delusional recent utterances, presenting Russia as the keeper of some core civilisational values, there is no suggestion that he has reached the point where he can acknowledge the position into which he has led his country. Prudence therefore requires us to assume that this war will not be over soon. But nor should it blind us to the possibility that events might move far faster than we assumed—first gradually, and then suddenly.

Note: I should thank the many accounts on Twitter that provide translations of the Russian blogs as well as news from the front lines. In no particular order: @wartranslated, @ChrisO_wiki, @RALee, @WarMonitor3, @JayinKyiv, @KyivIndependent, @IAPonomarenko, @Leonidragozin, @Hromadske and there are many more.