Is nuclear peace with North Korea possible?

North Korea’s recent public displays of new intercontinental and submarine-launched ballistic missiles have raised fresh concerns about the risks the regime in Pyongyang poses to the US mainland. As President Joe Biden’s administration reviews US policy towards the DPRK over the past four years and draws what lessons it can from Donald Trump’s nuclear summitry with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, it should consider a new arms-control approach.

The failure of Trump’s efforts should surprise no one. After all, prior US administrations’ initiatives to stop North Korea’s nuclear-arms program—including Bill Clinton’s ‘Agreed Framework’, the six-party talks during George W. Bush’s administration, and Barack Obama’s ‘Leap Day’ agreement—came to naught. Quite the contrary: North Korea withdrew from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in 2003, and has failed to abide by a 1992 accord with South Korea pledging to keep the Korean Peninsula free of nuclear weapons.

All this diplomatic activity leading nowhere raises a fundamental question: Does nuclear-arms control have a future on the peninsula?

It does, but not as currently practiced. It should be clear by now that Kim will not abolish his nuclear arsenal, or permit a verifiable nuclear freeze, as some have called for. The reason is simple: as with all nuclear-armed countries today, nuclear weapons remain the regime’s ultimate security blanket. The bomb also provides Kim with leverage over South Korea. The challenge, then, is to ensure that North Korea never uses its nuclear arsenal.

Realising this aim will require a combination of classic deterrence and new diplomatic thinking—specifically, a normalisation of US–North Korea ties. America currently provides deterrence on the peninsula through its offshore air- and sea-based nuclear umbrella over South Korea, while nearly 30,000 US troops in the country supplement more than three million active and reserve South Korean troops.

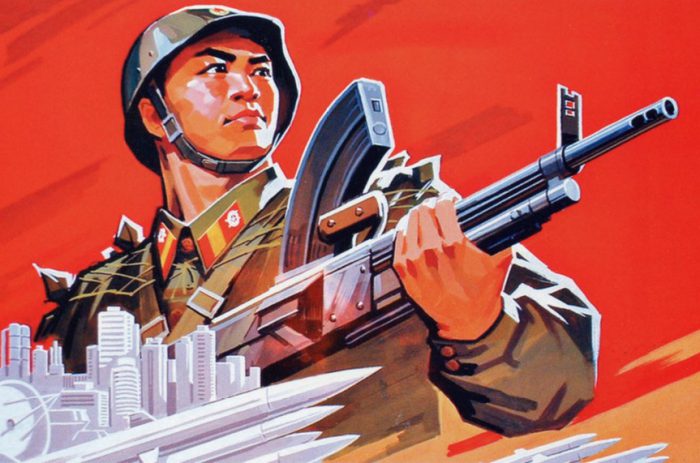

But relying on deterrence alone against North Korea cannot assuredly prevent or manage missteps, because the country’s isolation from the rest of the world breeds unique perils. Seclusion promotes pathological insecurities that could fuel misunderstanding and miscalculation. To complicate matters further, Kim is prone to grandiosity, military posturing and bullying.

Normal diplomatic ties buttressed by deterrence have provided a path to nuclear peace in other bilateral relationships, including between China and the United States. As menacing as North Korea is today, Cold War-era China under Mao Zedong’s leadership posed a far greater threat to American interests. Mao intervened in the Korean War against the US, fomented the Taiwan Strait crises later in the 1950s, and encouraged wars of national liberation against Western powers. When President John F. Kennedy’s administration entered office in 1961, it regarded China as a rising nuclear bête noire and considered military action against it.

But America did not bomb away, and Richard Nixon’s subsequent opening to China and the normalisation of relations during Jimmy Carter’s presidency neutralised US concerns. Despite the absence of a bilateral nuclear-arms limitation treaty, China’s arsenal remains largely a low-level issue amid current Sino-American tensions.

Similarly, US diplomatic ties with the Soviet Union dating back to the 1930s proved their worth in the 1962 Cuban missile crisis. As the US ramped up its military readiness to compel the Soviet Union to withdraw its nuclear missiles, the interaction between Washington-based Soviet diplomats and US officials proved pivotal in ending the standoff. Likewise, US diplomatic influence over Pakistan, and its ties with India, helped slow the momentum towards nuclear war during the 1999 Kargil conflict and in the aftermath of the 2001 Jaish-e-Mohammad terrorist attack on the Indian parliament.

To be sure, the centrality of North Korea’s nuclear enterprise to the survival of Kim’s regime would complicate any effort to normalise diplomatic relations. Then there are questions about how to build a diplomatic relationship. Can or should the process begin with the opening of embassies, in the hope that this will engender confidence and enable the two countries to address substantive issues? Or can negotiators get down to details immediately?

Either way, two priorities stand out. North Korea needs relief from international economic sanctions, and the US needs to eliminate North Korea’s capability to strike it with intercontinental ballistic missiles.

Sanctions, domestic mismanagement, natural disasters and Covid-19 have left North Korea’s economy—by Kim’s own admission—in desperate need of repair. For America, which currently lacks effective ballistic-missile defences, the prospect of being in North Korea’s nuclear crosshairs is unacceptable. Could this point to a possible trade-off, namely the lifting of sanctions in exchange for the elimination of missiles?

Such a deal would leave North Korea’s theatre nuclear force untouched and help mend the country’s economy while reducing the risk of a pre-emptive American strike. It would also immunise the US against a possible North Korean ICBM attack, leaving it better placed to meet South Korean and Japanese security needs. And with diplomatic representation in each other’s countries, both sides would have reliable channels to address disputes and manage relations generally.

To determine whether Kim’s regime would be open to serious negotiation, the Biden administration could initially endorse so-called Track II diplomacy—former US government and non-government interlocutors meeting informally with North Korean officials in third-party countries. If the outreach sparked interest in Pyongyang, the door to formal talks would open. America’s default option is to return to tried-and-failed efforts to persuade North Korea to disarm. The challenge will be to convince leaders on both sides that diplomatic normalisation leading to an ICBM–sanctions trade-off is the best path forward.