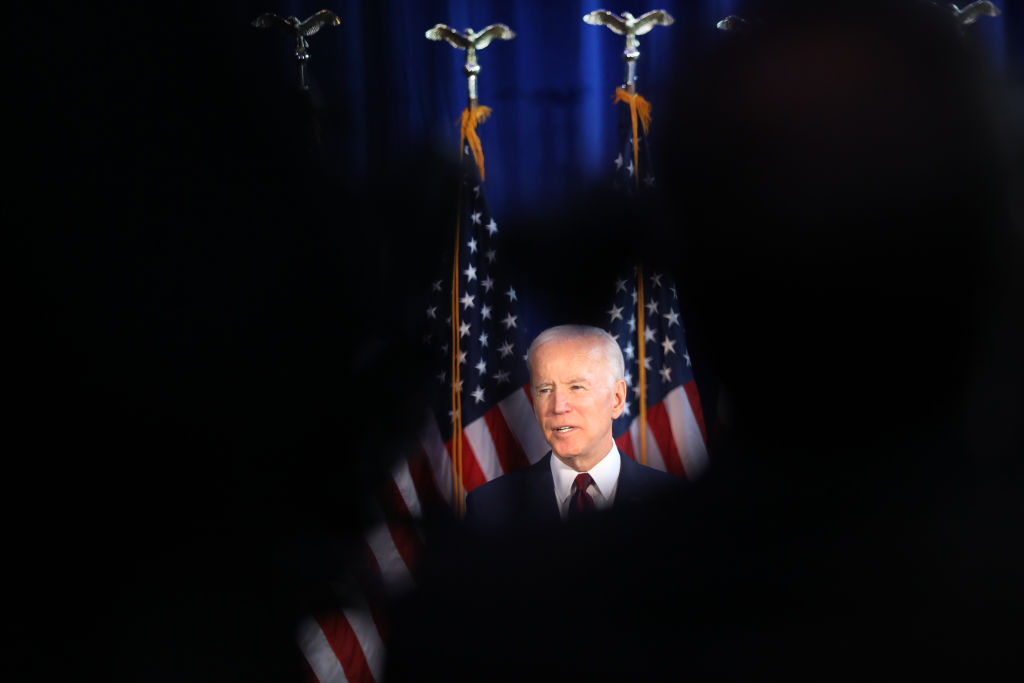

Will Biden’s two-pronged approach to the Middle East work?

President Joe Biden has shaken up the Middle East, putting America’s allies on notice and warning its adversaries not to take his administration for granted. He has revealed the traditional carrot-and-stick approach to promote American democratic values on the one hand, and maintain US geopolitical, economic and strategic interests in a vital but unstable region of the world on the other. Will this approach work?

As a zone of economic and strategic significance and, at the same time, frenemies, alliances and counter-alliances, the Middle East is a highly polarised, contested and conflict-ridden region. The former neonationalist and impulsive Republican president Donald Trump sought to boost America as the hegemonic player by building an Arab–Israeli alliance to confront Iran in the region. By the same token, he wanted to check the influence of an Iran–Russia axis in Syria, protect Israel and stonewall China to whatever extent possible in the region.

Whereas Trump’s approach heightened tensions and instability in the region, the Democratic, multilateralist and diplomatically savvy Biden aims to deal with the region in a way that emphasises the liberalist values in America’s foreign policy and, at the same time, safeguards its economic and strategic interests. In the process, he has stressed the need to resolve disputes with Iran, especially over the country’s nuclear program, regional influence and missile capability.

Yet he has balanced this with the launch last week of the first military operation of his presidency against Iran-allied Shia militias in Syria on the border with Iraq, primarily in retaliation for an attack presumably by an Iranian proxy on a coalition base in Iraq in mid-February. He has thus signalled to Tehran that when it comes to America’s strategic interests, he is not for turning. Tehran could not but view the development with disdain; yet, like the American side, it doesn’t want an escalation of hostilities. Iran recently declined a European Union invitation for talks with the US, but that may prove to be part of posturing, as Tehran would ultimately find it in its interest to reach a settlement with Washington to secure the lifting of America’s debilitating sanctions, though not at any cost.

Concurrently, Biden has unfolded a number of other policy initiatives in the region from which Tehran can take heart. They include halting the sale of American offensive weapons to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, ceasing US support for the Saudi-led Arab coalition operations in Yemen and calling for an end to the Yemen war, removing the Iran-backed Houthis (who are fighting the Saudi-supported government in Yemen) from the list of US terrorists, restoring some American aid to the Palestinian Authority, and rejecting unilateral action concerning construction of Israeli settlements on occupied territories. To top it all off, Washington has released the CIA report implicating directly the Saudi crown prince and de facto ruler, Mohammed bin Salman (MBS), in the gruesome killing of Saudi national and Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in 2018.

Although Secretary of State Antony Blinken has said that these measures are aimed at recalibrating rather than rupturing US relations with Saudi Arabia as an important ally, they amount to more than that. At this stage, Washington has refrained from sanctioning MBS directly, but its naming of him as the main culprit behind Khashoggi’s murder, plus the fact that Biden has bypassed MBS and communicated directly with his ageing father, King Salman, with an emphasis on human rights, leaves a huge stain on MBS’s reputation. It could prove to be very damaging to the crown prince.

Despite being in control of the Saudi coercive forces to guard his position, MBS now faces a serious credibility deficit in dealing with his domestic opponents, who include many older members of the royal family, and foreign adversaries. He may try to counter Washington’s moves by seeking to strengthen relations with China, especially through nuclear-armed Pakistan, which has close strategic ties with both the kingdom and China. However, given America’s traditional deep involvement in many aspects of the Saudi state, no amount of turning to China will bear meaningful fruit, even in the medium to long run.

Biden has initiated a course of Middle East policy to cover both sides of the equation: simultaneously calling for reform and protecting American interests. Where this approach will leave the US and the region, only time will tell. But whatever the ultimate outcome, his policy initiatives promise to be more soundly based than those pursued by his diabolic and ‘America first’ predecessor.