Malaysia’s new government could bring stability—or chaos

Malaysia’s sudden political evolution has dramatically shifted a decades-old steady government to the edge. The past few years of Malaysian politics have been messy and unpredictable, tarnished by corruption and a harsh economic climate. But, throughout this tension, the common thread of the Malay Agenda has remained.

Newly elected Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s Pakatan Harapan (Alliance of Hope) coalition is a collection of left-leaning parties hoping to reform Malaysian politics. But Anwar’s coalition lacks a solid ideology or plan to fulfil its vision of a ‘unity government’. Cutting the common thread of the Malay Agenda could lead to the revolutionised modern Malaysia of which Anwar dreams, or it could plunge the country into another period of political instability and increased violent extremism.

From independence in 1957 until 2018, the Barisan Nasional coalition led by the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) ruled Malaysia uninterrupted. Their model focused on the Malay Agenda, which gave special privileges and preference to ethnic Malays, while still providing minority groups with a seat at the table.

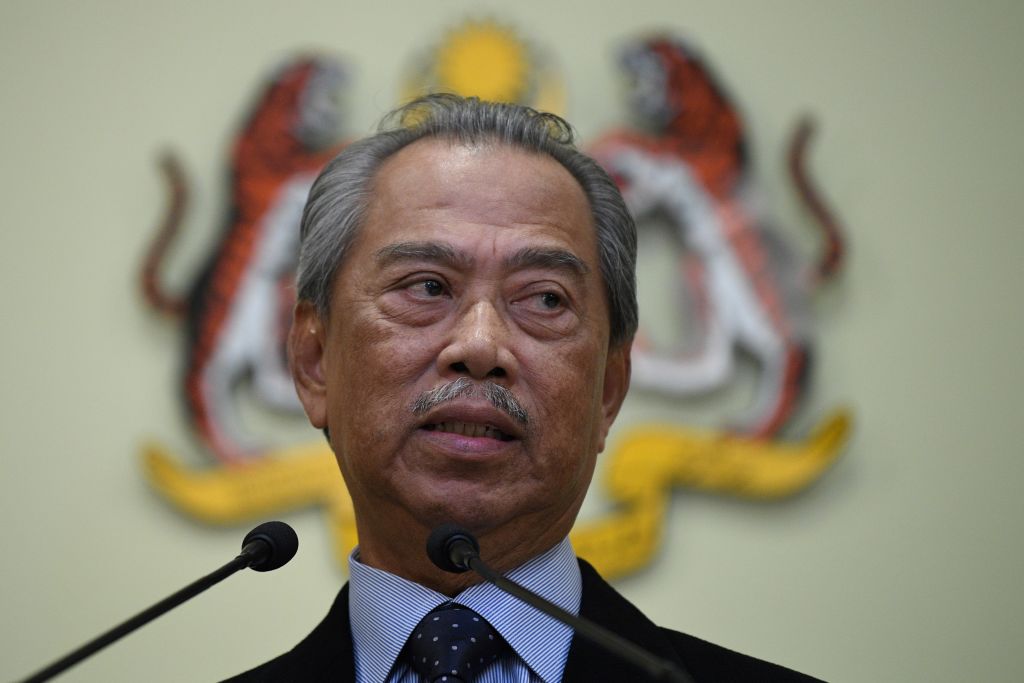

A shock occurred during the 2018 election, when an opposition coalition took control of the government promising reform and a more unified Malaysia under a new prime minister, Mahathir Mohammad. However, the vision of a modern Malaysia built on equality was short lived. Tensions among the various parties in parliament in 2020 led to a power grab. A new coalition made up of the three political parties promoting Malay-Muslim nationalism took control and installed Muhyiddin Yassin as prime minister.

Instability grew during the Covid-19 pandemic. Muhyiddin refused to remove emergency orders that restricted movement across the country. In response, UMNO withdrew support from the coalition, resulting in a third prime minister within three years, Ismail Sabri Yaakob, who took office in August 2021.

UMNO took encouragement from recent wins in local elections this year, as well as an opposition failing to form a solid ideology and coalition. With hopes of a clear victory in a general election to re-establish its control of Malaysian politics, UMNO dissolved the parliament and a snap poll was held on 19 November.

UMNO’s president predicted the party would win 80 seats, but it fell dramatically short, winning only 26. Malaysia had its first hung parliament. This forced King Al-Sultan Abdullah to attempt to create a unified government between Muhyiddin’s Perikatan Nasional and Anwar’s Pakatan Harapan. Muhyiddin turned down the king’s proposal due to differences on key policy issues between the two coalitions. Initially, UMNO initially refused to support either coalition, but after discussions with the king, agreed to support Anwar, allowing him to become the next prime minister of Malaysia.

Anwar’s victory has raised hopes for some that Malaysia is moving away from far-right-wing politics, potentially bridging the ethnic divides through compromise. But will UMNO play along?

UMNO’s backing was the deciding factor in Anwar’s installation as prime minister. An optimistic view is that it acted to support a united and stable government. However, it’s possible that it sees itself as kingmaker and hopes to be the deciding factor in government decisions as a last gasp at retaining power in Malaysian politics. Or, like it has done in the past, UMNO could threaten to leave the alliance if things don’t go its way, joining the Perikatan Nasional coalition, led by the Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS), to form a new government. UMNO’s general assembly next month and upcoming party elections will determine the stance it takes.

PAS was the most successful party in this year’s elections, winning 43 seats. PAS proved popular among the disgruntled voters who were tired of the corruption and infighting within UMNO and decided to vote instead for the party with the closest principles. The rise of PAS, though, is not solely due to the demise of UMNO. For years, PAS has slowly been building a constituency, playing a long game as a far-right movement built on capitalism, religion and nationalism.

PAS has been embroiled in controversy over concerns with its apparent support of the Taliban and extremist ideology. While Malaysia hasn’t officially recognised the Taliban-led government in Afghanistan, the previous government had begun informal engagement with stakeholders in Afghanistan. In March, PAS president Tan Sri Abdul Hadi Awang was sent as a special envoy to the Middle East and met with Taliban representatives in Qatar. Islamist fundamentalism has been on the rise in Malaysia for many years, and fundamentalist groups have looked to the Taliban as a success story to pursue stricter interpretations of Islam and Malay identity.

To PAS and other right-wing groups in Malaysia, Anwar’s victory threatens to erode Malay values and Islamic principles, which could lead to the demise of the Malay Agenda. Before, during and after the November election, social media platform TikTok experienced a surge in videos encouraging violence and hate. Some referenced the riots that followed the 13 May 1969 election, which resulted in 196 deaths. The heightened risk of violence led police to increase security across the country.

Terrorist activity in Malaysia has often sought to play on ethnic and religious divisions. The motive for the Movida Bar attack in 2016—the only Islamic State–linked terrorist attack to take place in Malaysia—was said to be the ‘un-Islamic’ behaviour. After protests at a Hindu temple resulted in the death of a Malay firefighter, Islamic State capitalised on the religious tension and inspired a plot, although unsuccessful, to avenge the firefighter’s death.

Extremist groups, within and outside Malaysia, will undoubtedly try to use the recent election and tension to inspire violence. Malaysia must effectively counter online extremism, which is perpetuating long-term grievances, and use suitable community engagement methods to dissuade radicalisation. Ultimately, the responsibility for ensuring internal peace and stability rests on the new government.

Anwar needs to balance a unity government and avoid the potential for violence and renewed instability that could come with a break in the coalition. And he must do all of that while strengthening Malaysia’s economy and position in a changing strategic landscape. Anwar’s personal experience of oppression makes him a relatable leader who could inspire political change.

While Malaysia is a multi-ethnic and multi-religious society, polarisation of these identities has greatly affected its politics. Malaysian politics will not stabilise unless Malaysians recognise the importance of diversity in the country and support a unified approach to move forward. An open question is how hardline Malays would respond to the replacing of the Malay Agenda. Anwar must show that he is the prime minister of all Malaysians and ensure the unity government is a success.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations has long been envisioned as a foundation stone for stability, security, and increased prosperity in Asia. But with uncertainty plaguing the political systems of Burma, Malaysia, and Thailand, ASEAN may be entering a period of policy and diplomatic inertia. At a time when China’s economic downturn and unilateral territorial claims are posing serious challenges to the region, ASEAN’s weakness could prove highly dangerous.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations has long been envisioned as a foundation stone for stability, security, and increased prosperity in Asia. But with uncertainty plaguing the political systems of Burma, Malaysia, and Thailand, ASEAN may be entering a period of policy and diplomatic inertia. At a time when China’s economic downturn and unilateral territorial claims are posing serious challenges to the region, ASEAN’s weakness could prove highly dangerous.