Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

For several years, Japan has been investing heavily in its diplomatic engagement with Indian Ocean island states and may now need to consider how to better extend that engagement to environmental security challenges. A recent environmental disaster in Mauritius caused by the grounding of a Japanese cargo ship showed how vulnerable island states are to environmental security threats. It also demonstrated the potential for reputational damage where adequate regional response mechanisms aren’t in place. There’s an opportunity for the Quad partners—Australia, Japan, India and the US—and other like-minded countries to work together to mitigate future threats.

In July this year, the MV Wakashio, a Japanese-owned and Panama-flagged cargo ship, ran aground on a coral reef just off the coast of Mauritius, setting the scene for what’s been called the worst environmental disaster ever experienced by that country. Thirteen days later, the ship began breaking apart, releasing some 1,000 tonnes of fuel oil over an area of 27 square kilometres and poisoning a major marine reserve and internationally recognised wetlands.

Mauritius declared a state of environmental emergency but had little capability of its own to respond. The government, NGOs, fishermen and local volunteers sought to contain the spill using small tourist boats, fishing vessels and homemade oil booms made from clothing, plastic bottles and dried sugar-cane leaves.

The accident led to major protests against the Mauritian government, and up to 75,000 protesters in the capital, Port Louis, called for the prime minister’s resignation.

The event prompted an international response from several countries and organisations. France took the lead by providing military and civilian equipment from nearby Réunion. Japan, India, Australia, the UK and the International Maritime Organization, among others, also provided equipment, materials and expert assistance.

Japan’s response included sending three teams of experts to assess the damage and advise on rehabilitation measures, although that led to some confusion when Japanese experts were reported as stating that there was ‘no damage’ to coral reefs and mangroves from spilled oil. The Japanese government also provided an initial US$34 million in assistance to purchase 100 new fishing boats. There’s little doubt that Japan will feel compelled to provide significant additional economic assistance in the future.

In recent years, Japan has considerably increased its focus on building its reputation and influence in the Indian Ocean region, including among the island states. This has included opening Japanese missions in the Maldives (2016), Mauritius (2017) and Seychelles (2019) and hosting a summit for leaders of 10 western Indian Ocean states in 2019. Those moves have been accompanied by a significant uptick in Japanese official development aid and infrastructure investment, including in Madagascar, the Maldives, Seychelles and Sri Lanka.

The financial liability of the Japanese owner of the Wakashio is tightly capped by an international treaty, but the reputational costs to Japan may be far higher, and this incident may have damaged some of the good work that Japan has been doing in the region in recent years.

The Indian Ocean may be one of the world’s most vulnerable regions to a range of environmental security threats, whether stemming from climate change, extreme weather events or human activities such as shipping and fishing. The Indian Ocean island states are on the front line of these challenges, as they’re among the most vulnerable to such threats and have the least capabilities to respond.

In recent years, there have been some useful initiatives for Indian Ocean islands in such areas as climate change adaptation, but there remains a need for a collaborative regional partnership, sponsored by major regional states and key users of the ocean, to help plan for and coordinate local and international responses to environmental security incidents. This could perhaps be a ‘Quad Plus’ project involving key countries with important interests in the Indian Ocean, such as Japan, India, France, the US and Australia.

Like the US Indo-Pacific Command–sponsored Pacific Environmental Security Partnership, an Indian Ocean environmental security partnership would build standing relationships among civil and military agencies to build local partners’ capacity, contribute to regional environmental strategy and mitigate threats and vulnerabilities.

As is the case with some standing humanitarian assistance and disaster relief arrangements elsewhere in the region (such as the FRANZ arrangement in the Pacific), an Indian Ocean environmental security partnership could also help coordinate and facilitate outside assistance in response to specific incidents.

Collective efforts must focus on threat prevention as well as response. In the Mauritius disaster, satellite data—which is available for all large commercial ships—clearly indicated that the Wakashio had been on course to strike the reef for several days after straying from usual shipping routes. Last-minute efforts by local authorities to contact the ship to change its course came too late.

Regional early-warning systems are being developed among Indian Ocean island states to predict extreme weather events. Existing technologies could also be used to develop an early-warning system for shipping disasters that would facilitate timely action to prevent future accidents.

There’s a moral imperative here. More developed countries gain many benefits from international trade (including international norms, such as freedom of the seas), but in many cases environmental challenges, including the environmental costs associated with shipping, are borne by regional countries. A regional environmental security partnership would be an important signal that larger countries recognise and understand the environmental challenges faced by Indo-Pacific island states.

An Australian ministerial visit to Brunei Darussalam normally triggers little strategic interest. But there may be more than meets the eye to Defence Minister Linda Reynolds’s meeting this week with Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah, sandwiched in between visits to Singapore and the Philippines. The fact that the visit took place during a pandemic, when only essential travel is meant to happen, is prima facie evidence that Canberra sees the defence relationship with Brunei as worth investing in. Why?

Brunei and Australia have had a memorandum of understanding on defence cooperation since 1999, providing a foundation for a low-key bilateral defence relationship. Brunei’s traditional and primary defence partner is the UK, symbolised by a resident Gurkha battalion and associated British Army units, hosted at the Sultan’s expense. Reynolds’s pre-departure announcement offered little indication of a substantive agenda, other than that Brunei will take over the ASEAN helm from Vietnam next year, while noting that Australia and Brunei are current co-chairs of the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus experts working group on military medicine. Not insignificant, but not an obvious case for ministerial face time.

Yet momentum has been quietly mounting in the defence relationship this year, including the first visit by an Australian submarine in March, which was accompanied by Chief of Navy Mike Noonan. In July, a Royal Australian Air Force P-8A Poseidon flew in for a bilateral drill (‘Exercise Penguin’, incongruously) with Brunei’s armed forces, which lack significant fixed-wing assets of their own. In August, the Royal Australian Navy and Royal Brunei Navy held a passage exercise on their way to Exercise RIMPAC, off Hawaii.

According to Reynolds’s post-visit statement, Brunei and Australia ‘share common interests in a secure, stable and open Indo-Pacific’. That may be so, but I see Australia’s recently invigorated interest in the sultanate as part of a broader effort to shore up Canberra’s access to maritime Southeast Asia and the South China Sea beyond its traditional partners and operating locations on the Malay Peninsula. This is reinforced by the inclusion of the Philippines on the defence minister’s travel itinerary. Australia’s military and defence relationship with the Philippines has shallow roots compared with Five Power Defence Arrangements (FPDA) partners Malaysia and Singapore, but an enhanced defence cooperation program has been in place since December 2019. The Australian Defence Force has deployed naval and air assets, with a significant training component, to the Philippines. Counterterrorism was the initial impetus, but Australia is also interested in the revival of Subic Bay as a prime location from which to sustain a forward naval presence in the South China Sea.

Malaysia, although not on Reynolds’s itinerary, remains arguably Australia’s most important and longstanding defence access partner in the subregion. Australia continues to conduct regular maritime surveillance flights over the South China Sea from Butterworth air base, near Penang, under arrangements dating back to 1980. RAAF aircraft enjoy superior access than US Navy P-8As which occasionally stage out of Malaysia.

Singapore, also in the FPDA and a comprehensive strategic partner in its own right, is another important node for Australia and officially described in the 2016 defence white paper as Australia’s most advanced defence interlocutor in Southeast Asia. Australia holds a reciprocal significance for Singapore as host to some of the island republic’s most important overseas training grounds and military exercises. Access is a two-way street, therefore, but cannot be guaranteed in extremis.

It makes sense for Canberra to negotiate broader access arrangements that better encompass the South China Sea and reduce risks that arise from being beholden to one or two countries for basing and logistics support that are critical to forward ADF operations in Southeast Asia. This would be consistent with the defence strategic update and its heightened focus on defending Southeast Asia as part of Australia’s core strategic environment. It can be inferred from the update that Canberra intends to maintain a naval and air presence in and around the South China Sea. This has been borne out by a regular tempo of ADF deployments despite the pandemic and a corresponding intensification of coordinated bilateral and trilateral deployments with the US Navy and Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Force. Australia’s impending participation in the Malabar naval exercises with India, Japan and the US stands to add a buttressing, quadrilateral dimension to this, though the drills themselves will remain centred on the Indian Ocean.

Australia’s defence relationship with Brunei is unlikely to ramp up dramatically. That’s not realistic. But Reynolds’s visit suggests that Canberra is doing what it can to pursue a more distributed network of access arrangements across maritime Southeast Asia. This is in Australia’s strategic interest, in a subregion where most states are actively hedging and willing partners are in limited supply, as Indonesia has recently reminded the United States. As is often the watchword these days, it makes sense to diversify one’s portfolio.

The same logic applies to Brunei, as a reluctant quasi-claimant in the South China Sea disputes. Until now, its closest defence partners have been the UK and Singapore. But as China encroaches ever closer in the South China Sea, potentially threatening Brunei’s offshore energy reserves and economic future, closer defence ties with Australia could be a seen as a prudent and calibrated addition to its own portfolio of security partners.

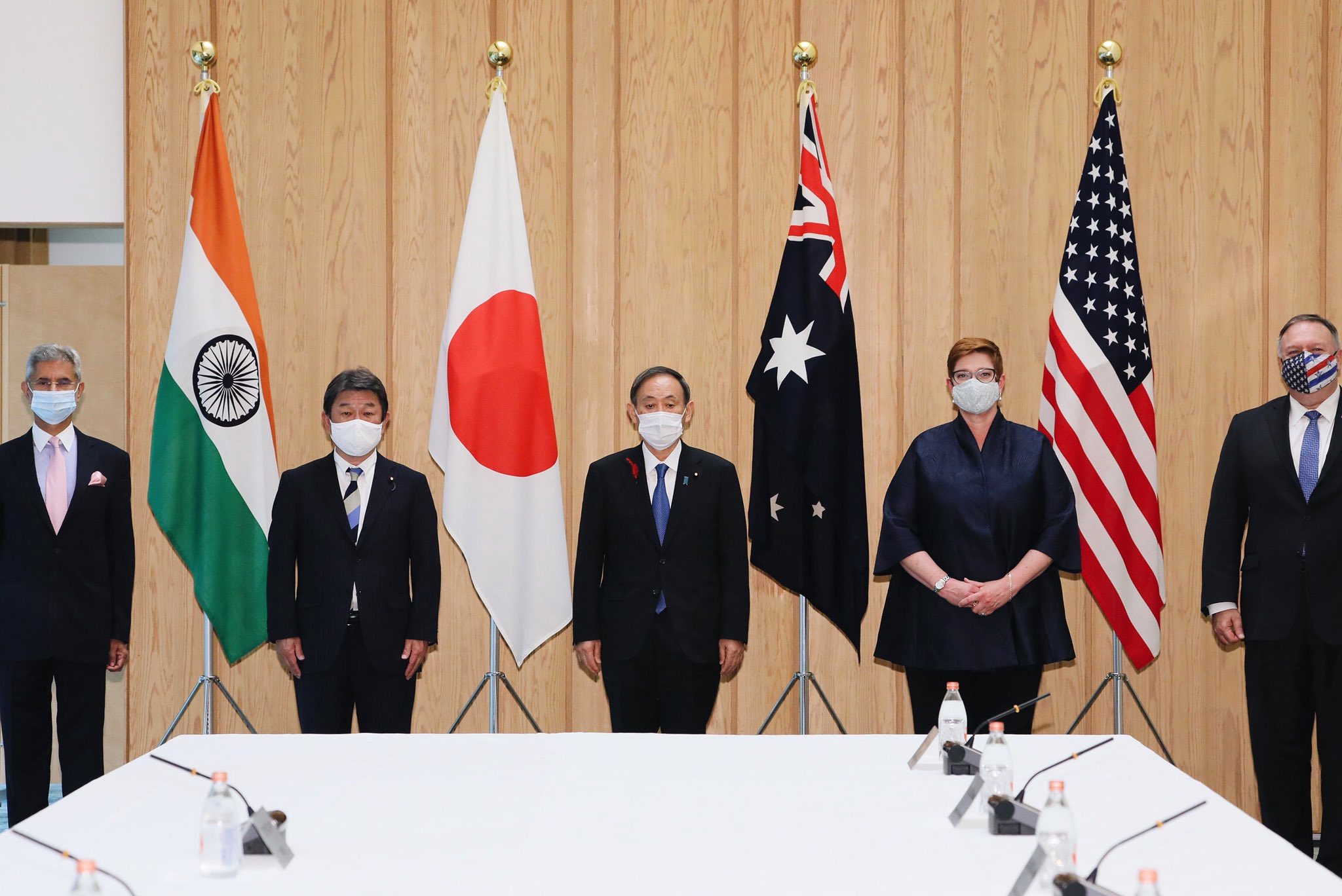

The Quad, a loose strategic coalition of the Indo-Pacific region’s four leading democracies, is rapidly solidifying this year in response to China’s aggressive foreign policy. Following a recent meeting of their foreign ministers in Tokyo, Australia, India, Japan and the United States are now actively working toward establishing a new multilateral security structure for the region. The idea is not to create an Asian version of NATO, but rather to develop a close security partnership founded on shared values and interests, including the rule of law, freedom of navigation, respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty, peaceful dispute resolution, free markets, and free trade.

China represents a growing challenge to all these principles. At a time when the world is struggling with a pandemic that originated in China, that country’s expansionism and rogue behaviour have lent new momentum to the Quad’s evolution towards a concrete formal security arrangement.

Of course, the Quad’s focus also extends beyond China, with the goal being to ensure a stable balance of power within a ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’. That concept was first articulated in 2016 by then-Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and has quickly become the linchpin of America’s regional strategy.

While all of the Quad partners agree in principle on the need for a free and open Indo-Pacific, it is Chinese expansionism that has catalysed their recent actions. China is forcing even distant powers like the United Kingdom, France and Germany to view a rules-based Indo-Pacific as central to international peace and security.

France, for example, has just appointed an ambassador for the Indo-Pacific, after unveiling a new strategy affirming the region’s importance in any stable, law-based, multipolar global order. And Germany, which currently holds the European Council presidency, has sought to develop an Indo-Pacific strategy for the European Union. In its own recently released policy guidelines, it calls for measures to ensure that rules prevail over a ‘might-makes-right’ approach in the Indo-Pacific. These developments suggest that in the coming years, Quad members will increasingly work with European partners to establish a strategic constellation of democracies capable of providing stability and an equilibrium of power in the Indo-Pacific.

After lying dormant for nine years, the Quad was resurrected in late 2017, but has really only gained momentum over the last year, when its consultations were elevated to the foreign-minister level. US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said this month that, ‘once we’ve institutionalised what we’re doing, the four of us together, we can begin to build out a true security framework, a fabric that can counter the challenge that the Chinese Communist Party presents to all of us.’

The Quad’s future, however, hinges on India, because the other three powers in the group are already tied by bilateral and trilateral security alliances among themselves. Australia and Japan are both under the US security (and nuclear) umbrella, whereas India not only shares a large land border with China, but also must confront Chinese territorial aggression on its own, as it is currently doing. China’s stealth land grabs in the northernmost Indian borderlands of Ladakh earlier this year have led to a major military standoff, raising the risks of further localised battles or another 1962-style frontier war.

It is precisely this aggression that has changed the strategic equation. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s authorisation of People’s Liberation Army incursions into the Himalayas has forced India itself to take a more confrontational position. It is now more likely than ever that the Quad will shift gears from consultation and coordination to become a de facto strategic alliance that plays a central role in a new multilateral security arrangement for the region.

This new architecture will bear little resemblance to America’s Cold War – era system, which rested on a patron–client framework, with the US as the ‘hub’ and its allies as the ‘spokes’. No such arrangement would work nowadays, for the simple reason that a country as large as India cannot become just another Japan to the US.

That’s why the US is working to coax India into a ‘soft alliance’ devoid of any treaty obligations. This effort will be on full display on 26 and 27 October, when Pompeo and US Defense Secretary Mark Esper visit New Delhi for joint consultations with their Indian counterparts. Most likely, this meeting will conclude with India signing on to the last of the four foundational agreements that the US maintains with its other close defence partners. Under these accords, both countries will be committed to providing reciprocal access to each other’s military facilities, securing military communications and sharing geospatial data from airborne and satellite sensors.

And having held multiple bilateral and trilateral military exercises with its Quad partners, India is likely to invite Australia to this year’s ‘Malabar’ naval war games with the US and Japan. This would mark the first-ever Quad military exercise; or, as the Chinese communist mouthpiece Global Times, put it, ‘it would signal that the Quad military alliance is officially formed’.

US foreign policy has always been most effective when it leverages cooperation with other countries to advance shared strategic objectives. Despite President Donald Trump’s undermining of US alliances, his administration has built the Quad into a promising coalition and has upgraded security ties with key Indo-Pacific partners, including Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, Australia, Thailand and India.

More fundamentally, the Quad’s consolidation is further evidence that the Xi regime’s aggressive policies are starting to backfire. International views of China have reached new lows this year. Yet the Chinese foreign ministry—doubling down on its ‘wolf warrior’ diplomacy—recently dismissed as ‘nonsense’ Pompeo’s plan to forge an international coalition against China. ‘He won’t see that day’, the ministry declared. ‘And his successors won’t see that day either, because that day will never, ever come.’

But that day is coming. The Quad once merely symbolised an emerging international effort to establish a discreet check on Chinese power. If Xi’s increasing threats towards Taiwan lead to military action, then a grand international coalition, with the Quad at its core, will become inevitable.

The World Bank predicts that the Maldives will be the South Asian nation hardest hit by the Covid-19 pandemic.

That’s not surprising given that 70% of the country’s GDP flows from tourism. The cancellation of all 26 weekly direct flights from China has had the biggest single impact. Visitors from China had become the largest tourist group up to September 2019. The cancellation of flights from India and Italy, the other two top tourist markets of 2019, has also affected the economy profoundly.

Although the country’s borders were reopened on 1 July, the number of arrivals has been extremely low. To encourage more visitors, the Maldives highlighted health benefits such as the isolation provided by the ‘one island, one resort’ concept. Visitors are screened for the virus on arrival and are not required to spend time in quarantine.

But, after the border lockdown was lifted, the number of Covid-19-positive cases rose rapidly. By early August, the Maldives was ranked sixth in Asia and first in South Asia in cases per capita.

The sudden build-up in numbers was mainly a result of residents of Malé, the capital, seeking to release frustrations and energy after three months of lockdown. For the younger generation, that involved going to coffee shops, restaurants and street corners without paying heed to government health measures.

The Maldives’ relationships with the three regional powers—China, India and Japan—remain largely the same as in pre-pandemic days. All three assisted with equipment and finance to combat the crisis. India stepped in as early as February, evacuating seven Maldivian students from Wuhan and providing 50,000 units of medicine, 580,000 kilograms of food and a medical team.

The Chinese government and private businesses also contributed with diagnostics, personal protective equipment, beds and ventilators. The relationship with Beijing is generally cordial, despite disagreement about the status of a free trade agreement which was rushed through parliament in 2018.

According to Beijing, the agreement falls under its Belt and Road Initiative, but the Maldivian government takes the view that none of China’s projects in the island nation are part of the BRI. It considers all Chinese projects as bilateral developmental aid.

Contrary to some claims, China’s recent demand for repayment of a US$10 million loan was not made to punish the Maldives for its close relations with India. In fact, it was part of a US$120 million loan to a resort owner associated with the previous administration and secured by a sovereign guarantee. This makes the loan the Maldivian government’s responsibility.

Under a ‘debt service suspension initiative’, China has reduced this year’s loan repayment to US$75 million from the scheduled US$100 million. Beijing has also indicated that it is prepared to discuss repayment terms for the remaining loans which were secured via state-owned companies.

The third power in the region, Japan, remains a close ally that gives aid to the Maldives in limited ways and in minimal amounts. During the Covid-19 crisis, Japan’s aid has been mostly financial. Apart from 9,000 surgical masks, assistance consisted of grants to UNICEF and the Red Crescent and to the United Nations Development Programme to support small and medium enterprises affected by Covid-19. Japan is not a rival to India or China in their drive for influence in South Asia.

Regardless of China’s efforts, India remains the dominant power in South Asia and the central Indian Ocean region. However, given the experiences of Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Djibouti, concerns remain about China’s potential dominance and ‘debt-trap diplomacy’. The Maldives owes US$1.5 billion to China, equivalent to 45% of the country’s national debt, and a potential debt-trap.

While there has been speculation from outside the Maldives that the economic crisis flowing from the pandemic will spark an increase in violent extremism, that doesn’t appear likely. Britain’s Foreign Office has warned, ‘Terrorists are likely to try to carry out attacks in the Maldives. Attacks could be indiscriminate, including in places frequented by expatriates and foreign travellers including tourists.’

But, historically, jihadist activities have not been tied to fluctuations in the country’s economy.

Covid-19 has created a bleak future for the Maldives, which now faces a projected budget deficit of MVR13 billion (A$1.2 billion).

This post is part of an ASPI research project on the vulnerability of Indo-Pacific island states in the age of Covid-19 being undertaken with the support of the Embassy of Japan in Australia.

The ‘Quad’ meeting of Indian, Japanese, US and Australian foreign ministers in Tokyo earlier this week has resulted in the usual suspects saying the usual things.

China’s foreign ministry expressed outrage and called on these four countries not to get together, but instead to work in the spirit of win–win, mutual respect and common destiny—that is, they should let Beijing get on with business without being interrupted.

Critics of the Quad point to the members’ differing national positions as showing that the group can never amount to much. Others say it’s perhaps growing into a type of Asian NATO.

All this rather misses two larger points: Quad cooperation keeps strengthening and support for the worldview it stands for keeps growing. Tuesday’s meeting was its second high-level ministerial meeting—something that we’d been told couldn’t happen because of national sensitivities over China. And the appeal of a way of running international partnerships and governments that is free of coercion and use of force is getting more and more attractive as an alternative to the world offered by Beijing’s current leadership.

A lot of this is because the ‘China model’ and what it means for those of us not part of the Chinese Communist Party leadership’s family elites are becoming more and more obvious as 2020 wears on.

It turns out that former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe’s idea for the Quad’s security and economic ‘diamond’ of some of the world’s most capable democracies is better suited to the world of the 2020s than it was when he launched it back in the mid-2000s.

Why is that? Well, it’s because populations and leaders in the Quad countries are joined by the populations of countries in Southeast Asia and across Europe in a shared assessment that the leaders of the People’s Republic of China wish to wield its economic, technological, military and strategic power in ways that damage the interests of this large chunk of the world’s population.

Three polls tell us this. Data from the Lowy Institute’s April 2020 survey showed a collapse in Australians’ trust in China over the past two years. Singaporean think tank ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute’s State of Southeast Asia 2020 survey report, with pre-pandemic data from late 2019, showed that only 1.5% of respondents across the 10 ASEAN countries see China as a benign and benevolent power.

And this week, the Pew Research Center has released data gathered between June and August this year on the views in 14 developed countries from Europe, North America and the Asia–Pacific region showing a uniform collapse in these populations’ favourable views of China under Xi Jinping. China is viewed unfavourably by more than 70% of the populations surveyed in all but two of the 14 countries, with young people sharing this assessment or being even more critical (for example, in South Korea). That’s an inversion of sentiment from 10 years ago, and much of the slide happened in 2020.

Interestingly, as an individual leader, Xi shares a very large unfavourable rating with US President Donald Trump, but China is distinguished from America by the fact that, unlike Trump, Xi is a product of a permanently ruling party. So it’s very likely that the growing concerns about China will endure while Xi remains leader of the CCP.

What’s worse for Beijing is that this isn’t about any particular bilateral relationship going bad, where the fault is as much on one side as the other. It’s a pretty uniform collapse in Beijing’s soft power that has correlated with China’s assertive and belligerent actions over the past year, built on a solid track record of coercion before then.

This matters because governments outside the authoritarian world tend to go where their populations lead them on general policy—and the populations across the Indo-Pacific, Europe and North America are looking rather consistent in wanting alternatives to a world or region dominated by the kind of Chinese state we see now.

The Quad members are promoting an Indo-Pacific free from coercion where sovereign states can cooperate for prosperity and security, which looks like an approach with rising popular support not just in the Indo-Pacific, but in large swathes of the world’s most capable and prosperous economies.

That groundswell in public sentiment provides a foundation for government action, and for economic reconfiguration away from the nasty dependencies we developed on operating in and through the jurisdiction governed by the CCP.

This takes us well beyond needing to parse the public statements of the four foreign ministers at the meeting to see the direction of cooperation. It also lets us know that as long as China continues on the path Xi has set for it, Quad cooperation will deepen, and partner countries across the region and the wider world will quietly welcome this, buoyed by popular support.

So, we’ll see more meetings and more quiet but substantial cooperation on topics like managing the pandemic, maritime security, countering disinformation and cyber hacking, and rebuilding economies in a post-Covid-19 world in ways that remove vulnerabilities and sovereign risks from overexposure to Beijing’s jurisdiction. All accompanied by more strident voices in Beijing wishing none of this was happening. That’s proving to be a virtuous circle.

The departure of Abe Shinzo as Japan’s leader opens a new era for Canberra’s quasi-alliance with Tokyo.

Australia is going to find out how much its small ‘a’ alliance is based on Abe and how much on more permanent shifts in Japan’s policy personality.

Was Abe an outlier or has he recast the mould for future leaders and Tokyo’s role in Asia? Japan’s longest-serving prime minister was transformative. Now we’ll see how deep the transformation goes.

Abe pushed for a stronger, more autonomous Japan rather than a comfortable Japan declining gently into middle-power ease.

Comfortable Japan would cuddle the peace of its pacifist strain, no longer wanting to serve as the US’s unsinkable aircraft carrier. The US–Japan alliance would fade as Tokyo decided the cost of resisting Beijing was too high. A Sinocentric future would be portrayed as Japan turning back to Asia.

One Abe-era change that fits either the strong or the comfortable narrative is the decision to drop Western name order and return to Asian tradition, putting the surname first. Thus, this column refers to Abe Shinzo, rather than the previous Shinzo Abe ordering. Here was a prime minister who changed things.

A mark of Abe’s impressive leadership was his ability to engage China but never bow to Beijing. As Ramesh Thakur notes, Abe’s ‘foreign-policy and national-security accomplishments will be key parts of his enduring legacy’. Rod Lyon mused that Abe’s ‘special relationship’ with Oz was atypical in the region—a level of strategic cooperation that no other Asian leader would reach for. Australia valued Abe’s declaration that Japan will have a military and security role in Asia’s future.

Abe’s influence touched much that matters in Canberra:

Abe was Asia’s pre-eminent Trump whisperer, setting the model for lavishing The Donald with love and dealing with a US that’s less predictable and less reliable. Malcolm Turnbull boasted he was tougher than Abe and got a better result with Trump, but Abe showed the way. An Australian prime minister used a Japanese prime minister to shape his approach to a US president. Mark that another Abe first for Australia–Japan relations.

In discussing how prime ministers direct the future, turn to the different responses of John Howard and Kevin Rudd to a shape-shifting Japan.

Howard was an alliance enthusiast; Rudd, an alliance sceptic. The Oz political parties have been slow to reach consensus on the weight the strategic relationship with Japan can carry.

Back in 2006, one of the best in the business, Des Ball, rated Japan as Australia’s fourth most important security partner, saying Australia’s security cooperation had intensified and expanded to the point where Japan ranked behind only the US, UK and New Zealand. And Ball was writing before Abe really got going.

In launching the US–Australia–Japan trilateral and in building bilateral defence ties, Howard’s government took the lead and Japan warmed slowly. When Foreign Minister Alexander Downer first broached the trilateral with his Japanese counterpart, he was told Australia was too insignificant as a security player for Tokyo to bother with.

Equally, Canberra was eager to go further than Tokyo in the joint declaration on security cooperation that Howard and Abe signed in March 2007. Howard wanted a formal treaty; Japan thought a treaty too difficult, both politically and constitutionally.

Rudd shared Tokyo’s hesitation. As opposition leader, he said there should be no step beyond the 2007 security declaration towards a full Australia–Japan defence pact, arguing, ‘To do so at this stage may unnecessarily tie our security interests to the vicissitudes of an unknown security policy future in northeast Asia.’

Abe used his second go as prime minister to charge up the trilateral dynamic and resurrect the Quad. In creating Quad 2.0, Abe was ably assisted by China’s wolfishness.

The man who is credited with sinking Quad 1.0 still worries about the quasi-alliance. In his 2018 memoir, The PM years, Rudd attacks with this question:

[W]hy would Australia want to consign the future of its bilateral relationship with China to the future health of the China–Japan relationship, where there were centuries of mutual toxicity? For Australia to embroil itself in an emerging military alliance with Japan against China, which is what the quad in reality was, in our judgment was incompatible with our national interest.

Rudd’s question is good, but China’s shoving was as important as Abe’s embrace.

Australia’s small ‘a’ alliance doesn’t involve a treaty-level commitment like the US–Japan and US–Australia alliances, but it’s a relationship that mirrors those pacts, based on shared interests and growing military and intelligence cooperation. A fresh element—both complicated and contentious—is the idea of Japan joining the Five Eyes intelligence club.

China’s bullying has shown Australia that a quasi-alliance with Japan is more a necessity than an option. Abe’s personality was persuasive, but Beijing’s policies have been decisive.

In his most recent New Year’s speech, Chinese President Xi Jinping declared that 2020 would be ‘a milestone’. Xi was right, but not in the way he expected. Far from having ‘friends in every corner of the world’, as he boasted in his speech, China has severely damaged its international reputation, alienated its partners and left itself with only one real lever of power: brute force. Whether the prospect of isolation thwarts Xi’s imperialist ambitions, however, remains to be seen.

Historians will most likely view 2020 as a watershed year. Thanks to Covid-19, many countries learned hard lessons about China-dependent supply chains, and international attitudes toward China’s communist regime shifted.

The tide began to turn when it was revealed that the Chinese Communist Party hid crucial information from the world about Covid-19, which was first detected in Wuhan—a finding confirmed by a recent US intelligence report. Making matters worse, Xi attempted to capitalise on the pandemic, first by hoarding medical products—a market China dominates—and then by stepping up aggressive expansionism, particularly in the Indo-Pacific region. This is driving rapid change in the region’s geostrategic landscape, with other powers preparing to counter China.

For starters, Japan now seems set to begin cooperating with the Five Eyes—the world’s oldest intelligence-gathering and -sharing alliance, comprising Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States. A new ‘Six Eyes’ alliance would serve as a crucial pillar of Indo-Pacific security.

Moreover, the so-called Quad—comprising Australia, India, Japan and the US—seems poised to deepen its strategic collaboration. This represents a notable shift for India, in particular, which has spent years attempting to appease China.

As US National Security Adviser Robert O’Brien recently noted, ‘the Chinese have been very aggressive with India’ lately. Since late April, the People’s Liberation Army has occupied several areas in the northern Indian region of Ladakh, turning up the heat on a long-simmering border conflict. This has left Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi with little choice but to change course.

Modi is considering inviting Australia to participate in the annual Malabar naval exercise with Japanese, American and Indian forces later this year. Australia withdrew from the exercise in 2008 when it involved only the US and India. Although Japan’s participation was regularised in 2015, India had hesitated to bring Australia back into the fold, for fear of provoking China. Not anymore. With Australia again involved in Malabar, the Quad grouping will have a formal, practical platform for naval drills.

Already, cooperation among Quad members is gaining some strategic heft. In June, Australia and India signed a mutual logistics support arrangement to increase military interoperability through bilateral defence activities. India has a similar pact with the US and is set to sign one with Japan shortly.

Japan, for its part, recently added Australia, India and the UK as defence intelligence sharing partners by tweaking its 2014 state secrets law, which previously included exchanges only with the US. This will strengthen Japanese security cooperation under 2016 legislation that redefined Japan’s US-imposed pacifist post-war constitution in such a way that Japan may now come to the aid of allies under attack.

Thus, the Indo-Pacific’s democracies are forging closer strategic bonds in response to China’s increasing aggression. The next logical step would be for these countries to play a more concerted, coordinated role in advancing broader regional security. The problem is that American, Australian, Indian and Japanese security interests are not entirely congruent.

For India and Japan, the security threat China poses is much more acute and immediate, as shown by China’s aggression against India and its increasingly frequent incursions into Japanese waters. Moreover, India is the only Quad member that maintains a land-based defence posture, and it faces the very real prospect of a serious conflict with China on its Himalayan border.

The US, by contrast, has never considered a land war against China. Its primary objective is to counter China’s geopolitical, ideological and economic challenges to America’s global pre-eminence. America’s pursuit of this objective will be President Donald Trump’s most consequential foreign policy legacy.

Australia, meanwhile, must engage in a delicate balancing act. While it wants to safeguard its values and regional stability, it remains economically dependent on China, which accounts for a third of its exports. So, even as Australia has pursued closer ties with the Quad, it has spurned US calls to join freedom-of-navigation operations in the South China Sea. As its foreign minister, Marise Payne, recently declared, Australia has ‘no intention of injuring’ its relationship with China.

If China continues pursuing an expansionist strategy, however, such hedging will no longer be justifiable. Japanese Defence Minister Taro Kono recently declared that the ‘consensus in the international community’ is that China must be ‘made to pay a high price’ for its muscular revisionism in the South and East China seas, the Himalayas and Hong Kong. He is right—the emphasis is on ‘high’.

As long as the costs of expansionism remain manageable, Xi will stay the course, seeking to exploit electoral politics and polarisation in major democracies. The Indo-Pacific’s major democratic powers must not let that happen, which means ensuring that the costs for China do not remain manageable for long.

Machiavelli famously wrote, ‘It is better to be feared than loved.’ Xi is not feared so much as hated. But that will mean little unless the Indo-Pacific’s major democracies get their act together, devise ways to stem Chinese expansionism, reconcile their security strategies, and contribute to building a rules-based regional order. Their vision must be clarified and translated into a well-defined policy approach, backed with real strategic weight. Otherwise, Xi will continue to use brute force to destabilise the Indo-Pacific further, possibly even starting a war.

To be part of an official interaction with the Republic of Korea is to receive frequent expressions of thanks for Australia’s role in the Korean War from 1950 to 1953. As an impoverished nation faced aggression from a Soviet-backed North Korea and from Chinese People’s Army ‘volunteers’, Australia quickly joined a UN-endorsed, US-led coalition to resist the aggression. It was no small commitment for an Australia recovering from World War II, involving 18,000 personnel and major combatants from all three services. In all, 340 Australians died and more than 1,200 were wounded. Our role, now often forgotten in Australia, is remembered in South Korea.

But the gratitude, though clearly genuine, bears little on the current defence or wider bilateral relationship, reflecting the very different circumstances that followed and those that exist today. The Korean War coalition has been maintained as the United Nations Command, a shell framework for continuing involvement, led and nurtured by the United States Forces Korea (USFK), which maintains around 28,500 troops on the peninsula to deter potential North Korean aggression.

Australia has been one of the most active, sometimes the most active, participant in this continuing arrangement. Aside from ‘Five Eyes’ partners, the participation of other members is largely token. Since 2010, Australia has led the UNC (Rear), located in Japan, and has assigned officers, currently around six, to the UNC headquarters in Korea. From 2014, it also assigned an embedded star-ranked officer to the USFK, and has regularly sent personnel to major exercises on the peninsula (reduced since President Donald Trump’s meetings with North Korea’s Kim Jong-un).

It would be reasonable to conclude from this that Australia is one of the Republic of Korea’s closest defence partners, but developing the relationship has been difficult. Korea is frequently listed by Australia among those partners with which we will build a closer defence relationship to confront the rapidly changing strategic circumstances in the region. But in reality, on both sides the effort has been minor and lacking in commitment, resources and enthusiasm.

In 2013, both countries agreed to establish annual meetings of foreign and defence ministers, making Australia the only country other than the US with which Korea had such an arrangement. This seemed like a significant step forward, but the process has underdelivered, producing anodyne statements and a ‘blueprint’ for action that has been modest indeed.

And Australian efforts in 2014–16 to negotiate a visiting forces agreement—in essence a ‘status of forces agreement’ by another name—were rebuffed by Korea. While Australian troops can exercise on the peninsula under the UNC umbrella, they cannot do so bilaterally. At the time, it appeared that Korea did not want to further antagonise China through a closer defence partnership with a close US ally. The absence of a visiting forces agreement has also truncated Australia’s ability to exercise with the US on the peninsula, as well as the opportunities to embed Australian Defence Force officers in US units deployed to the peninsula.

Australia has bought almost all of its ‘big ticket’ defence capability from the US, the UK and Europe, and never from an Asian partner. The closest it came was in 2016, when Japan’s conventional submarine was for a time the front runner in Australia’s next-generation submarine program. Australia also shortlisted Korean shipyard DSME in 2005 for construction of two naval fleet replenishment ships, but the contract was awarded to Spanish shipbuilder Navantia.

This may be about to change, offering both countries the opportunity to reboot their defence cooperation and to build a much closer defence partnership.

A process to acquire 30 Korean K9 self-propelled howitzers, to be built in Australia by project partners Samsung Techwin (now Hanwha Defence) and Raytheon, was abruptly cancelled following funding cuts by the government in 2012. Korea was angered by this late cancellation, viewing Australia as an unreliable partner.

But the project has been revived and decisions are understood to be imminent. The units are expected to be built in Geelong, generating 350 jobs at a time of recession. Whether this is a priority capability for the ADF in current and projected strategic and budgetary circumstances is a debate that is all but absent.

Hanwha Defence has also been shortlisted, along with Germany’s Rheinmetall, as potential supplier of the Australian Army’s next generation of around 450 infantry fighting vehicles under the Land 400 Phase 3 procurement. If Hanwha wins this second contract, due to be signed in 2022, the basis for a much stronger defence partnership will be laid.

Hanwha has developed the AS21 ‘Redback’ to meet Australian requirements, and Korea will promote a version of this to replace the Bradley fighting vehicle in the US. Hanwha is evaluating potential Australian suppliers to the program and envisages a major build in Australia. For both countries, supply-chain vulnerability has become a greater concern, so decentralised manufacturing and diversification of suppliers have grown in importance.

It may provide impetus to the bilateral defence relationship, offering training and collaboration opportunities, and building understanding in Australia of Korea’s advanced defence industrial capability, and vice versa. These opportunities have been limited by Korea’s focus on the threat from the north, a parochial view that it needs no other substantive defence partners than the US and a related dismissal of the value of the UNC.

Defence exports to, and greater collaboration with, a reliable regional partner may stimulate a Korean rethink. Korean concerns, publicly muted but real, about Washington’s reliability and Beijing’s aggressiveness were acutely felt by Korea when China responded with stiff and damaging sanctions to its agreement to host a US THAAD battery in 2016. These concerns are growing. With North Korea sabre-rattling again, and a parlous relationship with Japan, Koreans will again be feeling increasingly vulnerable.

But even if Korean equipment is chosen by Australia, it takes two to tango. Canberra has not always seemed to attach a high priority to bilateral defence collaboration with Seoul, seeing the main benefit of on-peninsula exercising as offering further opportunities for developing interoperability with the US. Australia’s 2020 defence strategic update makes clear that the priority has decisively returned to the region from the Middle East.

With tensions rising, unease about US capability and commitment, and pressures on national budgets to repair the damage from Covid-19, the time may have come for both countries to reassess this relative detachment and to give greater priority to defence and security collaboration. It’s in the strategic interests of both to do so.

On 29 May, The Times reported that the British government was set to propose reforms to the G7, an organisation established in 1975 to coordinate policy between the world’s largest and most advanced market economies. The UK proposal involves creating a new coalition of democracies, based on the Group of 7, with the addition of Australia, India and South Korea. It would be known as the ‘Democratic 10’, or ‘D10’ for short.

A few days later, US President Donald Trump threw his support behind the idea while giving some off-the-cuff remarks to a scrum of reporters. ‘I don’t feel that as a G7, it properly represents what’s going on in the world’, he said. ‘We want Australia, we want India, we want South Korea’, he went on, before adding: ‘And what do we have? That’s a nice group of countries right there!’

Although Trump also said he wanted to invite Moscow, he indicated that Canberra, New Delhi and Seoul would be invited to attend the upcoming G7 summit, which the US is due to host in 2020. Britain and Canada quickly scotched the US president’s proposal to include Russia; Moscow went on to state its reluctance to become involved in any formation that doesn’t include Beijing. The G7 summit was supposed to take place in June, but it has now been postponed until later in the year due to Covid-19.

The D10 makes sound strategic sense. The G7 as a forum for the leaders of the world’s largest powers to discuss strategic economic matters has long been superseded by the G20 (in 2008 after the global financial crisis). And the G7, despite ejecting Russia in 2014 for invading Ukraine, has lost much of its geopolitical rationale, not least because world power is no longer so concentrated in the Euro-Atlantic region. The Indo-Pacific is now the cockpit of the global economy and the stage for international geopolitical competition.

Will the D10 fly? Perhaps. Reducing the G7’s Eurocentricity would almost certainly entice countries with Indo-Pacific flanks, such as Japan, the US, Canada and France (through its overseas territories). The British proposal may also prove attractive to the three prospective new members—Australia, India and South Korea—because they would get to join what would likely become the top table for the world’s leading democracies. It may even appeal to European countries like Germany and Italy by giving them a voice in a region they have little means to influence by themselves.

And what would the D10 do? For Britain, the D10 is, in part, about ‘decoupling’ from China. It is about creating a new coalition to provide an alternative to China’s attempts to dominate world markets and set international standards, particularly in relation to next-generation technologies such as 5G.

Beijing’s mishandling of the Covid-19 outbreak and subsequent attempts to revise the 1984 Sino-British agreement on Hong Kong have irked London tremendously. Only in March did the British government confirm that Huawei would be allowed to remain inside its 5G system, if only on the so-called periphery—despite fierce warnings against the move from the US and Australia. Since then, China’s actions, combined with mounting pressure from backbench Conservative parliamentarians, including the newly formed China Research Group, as well as opposition parties, have tried to persuade Prime Minister Boris Johnson to backtrack on the Huawei decision.

The UK may appear an odd architect for a new democratic alliance, particularly one centred on the Indo-Pacific. Despite its overseas territories in the Indian and Pacific oceans, and its military reach into the region, Britain is an Atlantic power. But does that necessarily matter?

As an established democracy, the UK has a track record of bolting together successful international endeavours. It played a key role in the formation of the maritime law, the United Nations and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. It also put in place the Indo-Pacific’s only multinational security formation—the Five Power Defence Arrangements—which Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has suggested his country should join.

In any case, given the enormous and growing power that China could bring to bear against its adversaries, is it not time to think more strategically about the Indo-Pacific? Already, in terms of population, industrial yield and technological potential, China is the most powerful competitor the UK or US has ever faced. There is nothing to suggest that Xi Jinping—who became president for life in 2018—will cease his quest to dominate economically, technologically and strategically, as well as push back against liberal and democratic ideals. Are the other countries of the Indo-Pacific prepared?

The D10 should be embraced. It could start to consolidate the world’s leading democracies’ ability to uphold their autonomy and push back against authoritarian revisionists. It would help ensure that the Indo-Pacific of the 21st century remains free and open and does not become controlled and closed.

One of the most interesting things in international affairs is when a country’s role starts shifting. Over the past decade, I’ve watched the evolution of India’s self-awareness from its traditional anti-great-power stance to the realisation that it’s on the cusp of being a great power itself. What sort of global power will India become?

The annual multilateral Raisina Dialogue provides some insights into this question. India’s flagship conference on geopolitics and geoeconomics this year attracted more than 700 attendees, including 12 foreign ministers and seven former heads of state. It was a jam-packed five days, including associated think tank events, providing a window into Indian strategic debates.

Some new themes were evident this year in discussions about India and how it sees its role.

First, there was more recognition than I’ve heard before that India might have benefited from the liberal international order and will miss it. Professor Ummu Salma Baya of Jawaharlal Nehru University’s Centre for European Studies eloquently described the sense of the liberal international order fraying into disorder. Shashi Tharoor quipped that the liberal world order didn’t always live up to each part of its name, but did create much good.

Second, some Indian speakers noted that, as global rules continue to come under strain, India might want to play a bigger role in shaping global norms. Shashi Tharoor and Samir Saran, authors of The new world disorder and the Indian imperative, argue that India has a major part to play in shaping the regimes of the future given its size, growing clout and stake in practically every major multilateral organisation. As characterised by Rudra Chaudhuri of Carnegie India, India has been ‘a country that believes in its own exceptionalism’ and ‘that it is generally seen as sovereignty hog’. Building global rules requires a different approach.

India was encouraged to embrace such a role by international speakers, including former Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper, who called on India to aspire to be a constructive global power, and former NATO secretary-general Anders Fogh Rasmussen, who asked India to step up and contribute to a global alliance of democracies to set the norms for the future.

Third, there were a few voices urging a different approach to trade. C. Raja Mohan of the Institute of South Asian Studies was provocative in arguing that New Dehli’s negativity towards international trade has made India ‘part of the problem’ in the breakdown of global rules. With US$3 trillion GDP, linked to global exports and imports, ‘Can India remain Mr No?’, he asked. He noted that India has stood aside from rules on e-commerce and is not part of group trying to reform the World Trade Organization. He argued that as one of the big economic powers, India needs to fundamentally review its position: ‘Delhi needs a fresh perspective.’

Professor Gulshan Sachdeva of JNU’s Centre for European Studies noted that India has unilaterally cancelled investment treaties with Europe and others. Mihir Sharma of the Observer Research Foundation pointed out that, in the past five years, India hasn’t signed any major trade deals, hasn’t endorsed the Belt and Road Initiative, and has decided to stay outside the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. He suggested that an observer looking at India as an economy with potential would see that it isn’t ready for the kind of integration that’s happening in Asia and elsewhere the world, with negative effects on its economy. ‘It’s the right time to bring trade issues onto the agenda’, he said.

These were still minority views. A talk by the commerce and industry minister, Piyush Goyal, showed India’s traditional attitude towards global trade in full force. There was consensus that India is not going to join RCEP. While immediate change to India’s stance on global trade seem unlikely, it’s interesting is that some voices have started arguing for a different approach.

Bringing these themes together, the talk on ‘the Indian way’ by India’s external affairs minister, S. Jaishankar, was instructive. According to the minister, it is not the Indian way to be a disruptive power internationally; it should be a stabilising power. It’s not the Indian way to be self-centred; it is important to be global and rule-abiding and consultative. The Indian way is to bring ‘its capacities to bear on the international system for global good’.

But he went on to say that the Indian way, ‘now especially, would be to be more of a decider or a shaper rather than an abstainer’. That includes shaping ‘the international relations discourse, the concepts, the ideas, the debates’. He stressed that it’s not about taking power, but noted that as India grows in its capacities and influence, it might begin expressing itself a little more firmly and decisively than in the past. ‘I think the image of being reluctant, of shying away [doesn’t] hold true anymore.”

While couched in terms that have continuity with India’s past—’India owes it to itself and to the world to be a just power, a fair power, to be a standard-bearer for the south. I think it’s part of our history, it’s part of our political inheritance’—there was also a desire to see India punch at its weight, such as on climate change.

Jaishankar also noted that India’s international personality will be an extrapolation of its national personality, its heritage and its talents: ‘We are a political democracy, we are a pluralistic society, we are a market economy, we have historically been very open to the world. I think you will see all those traits reflect themselves.’

An India that doesn’t shy away from exercising influence may have more time for Australia. In the minister’s words:

Today we really think the India–Australia relationship is poised for a big jump because … when we look at the world, at the strategic picture, we look at the political picture. I think we are two countries whose interests and approaches are really very convergent.

There’s also a realisation that countries like India and Australia need to step up and play a greater role in terms of global responsibilities, regional responsibilities because there is a growing deficit in that regard.

The critical issues of the time are ones that Australia and India can work together on.

Raisina showed the Indian way: big and argumentative, publicly discussing and deciding what sort of country it should be. India will be debating its role in global affairs for some time to come.