Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Australia’s second WPS national action plan outlines how Australia will live up to its commitments to the women, peace and security agenda. ASPI’s Emilia Currey and Lisa Sharland discuss the plan, how it differs from the first NAP, the challenges that need to be overcome as well as domestic concerns.

Have you ever considered a career in intelligence? ASPI’s Michael Shoebridge speaks with Carl and Karinda from the Office of National Intelligence about career pathways and what the future of the intelligence workforce might be.

The Strategist’s Brendan Nicholson is joined by co-author of a new ASPI report on Indo-Pacific island states during Covid-19, the University of Tasmania’s Richard Herr, to discuss the range of responses to the pandemic across the region and the vulnerabilities and opportunities it created.

‘Good fences make good neighbours.’ This line from Robert Frost’s famous poem ‘Mending Wall’ is often misunderstood. Some take it to mean that having hard barriers in place will keep neighbours apart and therefore prevent problems. However, in the poem the very action of rebuilding the fence together every year is what brings the neighbours closer. By spending time together, talking and repairing the fence, they become better neighbours.

Australia’s future is deeply intertwined with that of its Indo-Pacific neighbours and we have an enduring interest in the sovereignty, stability, security and prosperity of the region. This benefits all who live in it. Building national resilience in Australia shouldn’t be seen only through the lens of strengthening domestic systems, economic settings, critical infrastructure and other programs. It is also about ensuring we have a resilient neighbourhood.

The Australian government has a long history of supporting capacity-building initiatives across the region with this objective in mind. The initiatives are delivered through aid programs, defence cooperation programs, medical and health projects, academic and professional exchange programs, and so on. They seek to help build stronger communities and more stable governments so that Australia can improve its own economic and security interests, and therefore become more resilient.

However, this policy approach, while well intentioned, is not always matched with well-designed, practical initiatives and engagement. Sometimes that’s due to a lack of country-specific literacy, which leads to programs being designed and delivered in an Australian-centric manner. We need to build a deeper understanding of the region among our policymakers, business leaders and academic institutions (secondary and tertiary). Anyone who understands the region will know that success is underpinned by personal connections and networks. These take time to develop, along with patience and a strong understanding of local drivers and conditions.

To explore how simple, well-designed programs can succeed, let’s look to one of our largest, most important, diverse and dynamic neighbours, the Republic of Indonesia.

Australian politicians of both persuasions regularly state that Indonesia is one of Australia’s most important strategic partners. What this actually means in terms of Australia’s foreign-policy priorities and practices is, however, often contested. While there have been some excellent achievements—most recently with the finalisation of the Indonesia–Australia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement, for which the two governments should be applauded—misperceptions and misunderstandings remain on both sides.

Looking back a decade, in his historic 2010 speech to the Australian parliament, Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono highlighted the dangers posed by the perceptions that Indonesians and Australians have of one another. He said, ‘I was taken aback when I learned that in a recent Lowy Institute survey … there are Australians who still see Indonesia as an authoritarian country, as a military dictatorship, as a hotbed of Islamic extremism or even as an expansionist power.’ The president highlighted that a key to overcoming these barriers is better people-to-people linkages.

Progress has been made, but we need to continue to strengthen these people-to-people linkages. Below are two small, but important, practical models that could be followed.

In 2011, the Australian Department of Defence launched the Indonesia–Australia Defence Alumni Association, or IKAHAN. The purpose of IKAHAN is to foster relationships across the large, diverse, and sometimes misunderstood, bilateral defence relationship. It provides a platform to exchange ideas, interact in new ways, build relationships among future leaders on both sides, dispel myths and encourage dialogue between the senior leadership.

Notable Australian members include former and current governors-general of Australia, former senior Australian Defence Force leaders, leading academics and thought leaders. There’s a similarly impressive membership on the Indonesian side. Senior leadership is important, but so is future leadership, and IKAHAN boasts a large cohort of junior members. The simple act of establishing a vehicle to better promote understanding and engagement that resonates for both sides has added a depth to the bilateral relationship not imagined before.

Coincidentally, in 2011 the Northern Territory Cattlemen’s Association established an exchange program to bring Indonesian animal husbandry students to northern Australia to learn about Australian cattle-production systems and foster greater cross-industry understanding of the unique challenges faced by producers in both countries. The Indonesian students typically spend eight weeks in Australia gaining practical hands-on training working alongside Australian stockmen and -women on northern cattle properties. Several of the Australian host families then visit Indonesia to reunite with the students they hosted in Australia and to learn more about Indonesian agriculture and its requirements as a market.

Many of these Indonesian students go on to become leaders in their field. These relationships can’t be valued in dollar terms but hold an immeasurable value in one of Australia’s most important live-export markets.

Both programs continue today and both are in important sectors that have been tested in the past and will likely be tested in the future. The philosophy and approach taken to weatherproof these sectors can be applied across the Indo-Pacific region. By adding ballast to our bilateral relationships through people-to-people linkages, we can better manage future shocks and therefore add resilience to Australia and our neighbourhood.

Practical first steps that we can take to help build this ballast include increasing the capacity and depth of Asian studies programs in our schools and universities, designing genuine collaborative government programs and projects (which will often require doing things differently to the Canberra norm and mindset), and building Asia-capable business leaders who better understand our northern neighbourhood—which equates to almost 60% of the global population.

As we move out of the pandemic, Australia has the opportunity as a middle power to match our rhetoric with practical action. We have the opportunity to become a good neighbour. Let’s not let it pass us by.

At first glance, given their geographic distance, there seems little pushing France and Indonesia closer together. But from Paris’s perspective, the French territories in the region and the fact that 93% of France’s exclusive economic zone is in the Indian and Pacific Oceans are compelling reasons for it to seek a greater presence in the Indo-Pacific. Indeed, France is the only EU country with a permanent military force stationed in the Indian Ocean, and Indonesia, Southeast Asia’s largest maritime state, is a natural partner.

Jakarta’s desire to build up its maritime muscle and keep its commitment to strategic nonalignment make the EU an attractive alternative source of equipment, and France is one of the world’s top five arms exporters. France and Indonesia share several of the big-picture strategic interests in the Indo-Pacific, such as a stable and peaceful South China Sea. They’ve also been busily negotiating a defence cooperation agreement which, once signed, will be France’s only such agreement in Southeast Asia.

So, what are the growth areas for this nascent defence partnership? Is there potential to extend the bilateral relationship into other areas? And what does a closer Indonesian–French connection mean for Australia?

The first key area of growth is driven by Indonesia’s interest in the French defence industry. For Jakarta, France represents an important source of high-end warfighting capability. Indonesia’s defence minister, Prabowo Subianto, has wasted no time cultivating this relationship—last year, he made two visits to Paris and spoke on the phone with his French counterpart, Florence Parly.

So it comes as little surprise that a list of proposed big-ticket items released by Indonesia’s Defense Ministry earlier this year included 36 Rafale fighter jets and five modified Scorpène-class submarines. Indonesia has also expressed interest in two of Naval Group’s Gowind-class corvettes. For its part, France appears keen as well. Dassault Aviation senior officials held talks about the Rafale deal with Indonesia’s Defense Ministry in Jakarta last month.

Both sides are also beginning to unlock the potential for joint military training. Last year, a meeting between army officials resulted in an agreement for Indonesian soldiers to exercise with French troops in 2021. Another growth area for army cooperation could be peacekeeping. French and Indonesian blue helmets are in contact in Francophone countries like Mali and Central African Republic, but also Lebanon. In the past, the Indonesian peacekeeping training centre in Sentul employed a civilian French-language instructor.

Indonesia is the eighth largest peacekeeper-contributing nation and France the sixth largest contributor to the UN peacekeeping budget, so the two countries have ample lessons to share on promoting best practice, accountability and initiatives supporting women in peace and security. These kinds of exchanges could begin virtually and, once personnel are vaccinated against Covid-19, could continue in person to strengthen people-to-people ties.

France also has a highly developed navy with which Indonesia could exercise on issues pertinent to its needs. The Covid crisis has revealed new opportunities; analysts Alban Sciascia and Anastasia Febiola Sumarauw argued last year that Indonesia’s navy might be a ‘forgotten pandemic asset’. Especially in an archipelago, developing hospital-ship-like capacities leaves the military with assets it can deploy in both amphibious operations and diplomatic health initiatives.

France deployed its three Mistral-class landing helicopter docks for Covid relief operations last year, suggesting there’s much to share between the countries in seaborne humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. The alternate planning years for French-led Exercise Southern Cross (Croix du Sud), held north of New Caledonia, which includes partners from Indonesia, Australia and the Pacific, would be an ideal place to begin those discussions.

France and Indonesia could also capitalise on their memberships of the Western Pacific and Indian Ocean naval symposiums. Developing a dedicated bilateral naval dialogue alongside either symposium would be a cost- and time-efficient means of boosting information sharing and ties between personnel. France is the chair of the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium until 2022, so it’s an ideal time to explore these options.

From Canberra’s perspective, closer ties between Paris and Jakarta are undoubtedly a positive thing. For one, Australia supports France’s involvement in the Indo-Pacific. The 2018 vision statement on the France–Australia relationship supports closer bilateral cooperation with like-minded partners to bolster regional maritime security, particularly in the Indian Ocean.

Indonesia is a key player in this. Its French naval procurements, if and when delivered, represent a leap forward in its ability to patrol and secure strategic sea lanes not just in the Lombok and Sunda Straits but around the Natuna Islands and Indian Ocean rim. Likewise, the Rafales would boost the Indonesian air force’s confidence and the country’s strategic posture. Greater engagement between Indonesia’s and France’s naval personnel helps build critical ties and foster shared understandings of Indo-Pacific security.

France’s increased Indo-Pacific interest also opens an even wider window of opportunity for Jakarta to work minilaterally with willing maritime partners. Ties between Australia, India and France expanded further last year with the first virtual senior officials’ meeting, undoubtedly with an eye to further Indian Ocean cooperation. There’s certainly potential to find niche areas of overlap between that grouping and the more established Indonesia–Australia–India trilateral, which is currently developing a new maritime exercise. France and India are stepping up naval cooperation, with the first amphibious exercise between the French and the Indian navies, Varuna 21, being held in India.

As Defence Minister Linda Reynolds noted last year at the launch of Australia’s 2020 defence strategic update, the ‘key for the future’ is bringing together the various mini- and multilaterals to strengthen regional security. For Indonesia, that means not just committing even further to capability upgrades but considering carefully how to invest in development and training of its navy and coast guard personnel. The Indo-Pacific continues to be a site of growing dynamism but also increased threats to stability.

With all this attention on regional drivers, however, it’s easy to lose sight of domestic politics. Some of the impetus for closer Franco-Indonesian cooperation in Jakarta, particularly in securing French capability, is from Prabowo’s desire to deliver quick results as defence minister. It’s not that his position is tenuous; rather, it strengthens his claim—if he chooses to run for the presidency in 2024—that he can protect Indonesia and therefore will make a good president. If he’s successful, there could be even more closeness with a Francophile as leader. If not, at least the recent ground gained wouldn’t be undone, given France’s enduring regional, especially maritime, interests.

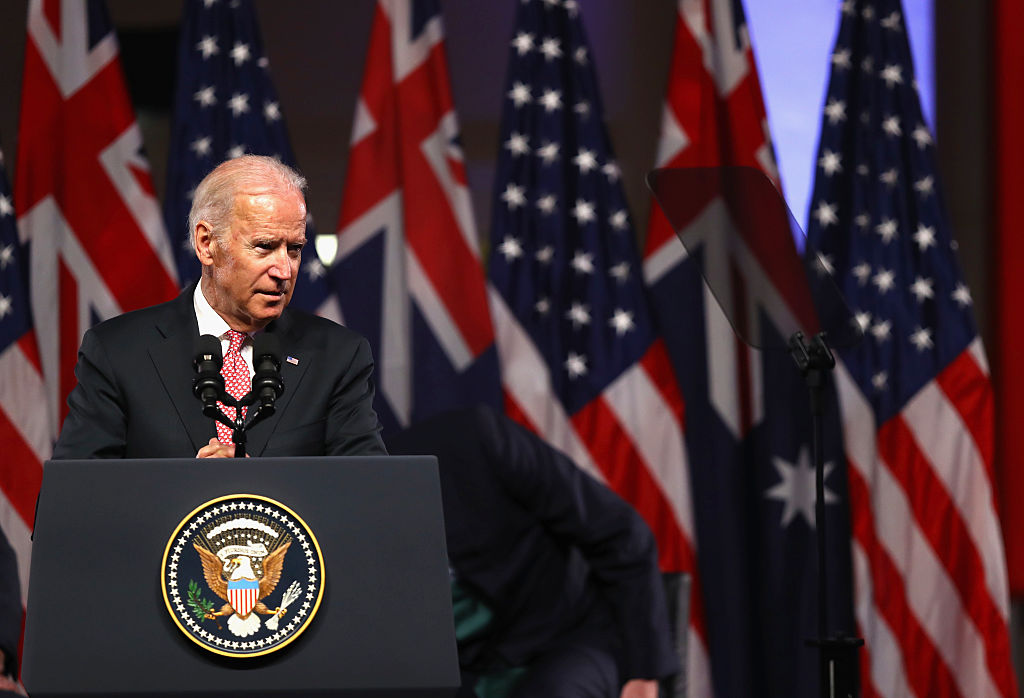

In his inaugural address, US President Joe Biden declared that Americans ‘will be judged’ for how they ‘resolve the cascading crises of our era’. He expressed confidence that the country would ‘rise to the occasion’, and pledged that the United States would lead ‘not merely by the example of our power but by the power of our example’.

The contrast with President Donald Trump’s divisive, isolationist rhetoric couldn’t be sharper. But adopting a different tone is easier than reversing America’s relative decline. To do that, Biden will need to provide wise, forward-looking leadership. And that doesn’t necessarily mean breaking with everything that Trump did.

America’s debilitating political polarisation has undermined its international standing. Partisan considerations have hampered—even precluded—the pursuit of long-term foreign policy objectives. US policy towards a declining Russia, for example, has become hostage to US domestic politics.

Biden’s calls for unity reflect his awareness of this. But the truth is that healing the deep rupture in US society may be beyond any president’s ability, not least because so many Republican voters seem to have abandoned all faith in evidence and expertise. So, rather than becoming consumed by domestic political divisions, Biden must rise above them.

And yet, there is one area where there’s broad bipartisan consensus: the need to stand up to China. Trump understood this. Indeed, his tough China policy is his most consequential—and constructive—foreign policy legacy. Unless Biden pursues a similar approach, the erosion of US global leadership will become inexorable.

The Indo-Pacific region—a global economic hub and geopolitical hotspot—is central to an effective China strategy. Recognising the region’s immense importance to the world order, Beijing has been steadily reshaping it to serve Chinese interests, using heavy-handed economic coercion, political repression and aggressive expansionism to have its way from the Himalayas and Hong Kong to the South and East China Seas.

The only way to preserve a stable regional balance of power is with a rules-based, democracy-led order—or, as the Trump administration put it, a ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’. Over the past year, this vision has spurred the region’s democracies to deepen their strategic bonds and inspired even the faraway democracies of Europe to implement supportive policies. Under the Biden administration’s leadership, countries must now build on this progress, creating a true concert of democracies capable of providing stability and balance in the Indo-Pacific.

Biden seems to understand this. He has made clear his intention to build a united democratic front to counter China. But he is also at risk of undermining his own vision.

For starters, Biden didn’t embrace the term ‘Indo-Pacific’ until after his electoral victory, and when he did, he replaced ‘free and open’ with ‘secure and prosperous’. But, whereas ‘free and open’ automatically implies a rules-based, democracy-led order, ‘secure and prosperous’ leaves room for the inclusion of—and even leadership by—autocratic regimes. This ignores the crux of the Indo-Pacific challenge: a revisionist China is actively seeking to supplant the US as the region’s dominant power.

Making matters worse, Biden has signalled a possible reset of ties with China. This would play right into China’s hands.

Trump’s China policy was not just about trade or human rights. It sent the (right) message that China is a predatory communist state without political legitimacy or the rule of law. This helped to tip the scales in America’s favour. Over the past year, unfavourable perceptions of China reached historic highs in many countries. While this was largely because of the made-in-China Covid-19 pandemic, Trump’s ideological onslaught and China’s own aggression—such as on its Himalayan border with India—also played a role.

If the Biden administration abandons economic decoupling and treats China as a major competitor, rather than an implacable adversary, it will tip the scales in the opposite direction, relieving pressure on Chinese President Xi Jinping’s regime and undermining faith in US leadership. This could embolden Beijing to destabilise the Indo-Pacific further, with Taiwan possibly its next direct target.

Moreover, US conciliation would give India second thoughts about aligning itself too closely with the US, and would likely lead to Japan’s militarisation—a potential game-changer in the Indo-Pacific. It would also facilitate China’s efforts to leverage its vast market to draw in America’s democratic allies—a risk underscored by its recent investment deal with the European Union. All of this would undermine efforts to forge the united democratic front Biden envisions, compounding the threat of China’s aggressive authoritarianism.

The worst choice Biden could make would be to seek shared leadership with China in the Indo-Pacific, as some are advocating. Worryingly, Biden’s team doesn’t seem clear on this. In a 2019 essay, Jake Sullivan (Biden’s national security adviser) and Kurt Campbell (Biden’s ‘Indo-Pacific czar’ at the National Security Council) championed ‘coexistence with China’, describing the country as ‘an essential US partner’.

To be sure, Sullivan and Campbell didn’t call for Sino-American joint hegemony, in the Indo-Pacific or beyond. But they also didn’t take the clear and necessary position that the US must forge a concert of democracies to bring sustained multilateral pressure to bear on China.

After four years of Trump, Biden is right to tout the importance of domestic unity. But a tough line on China is one of the few policy areas behind which Americans can unite. More important, it is the only way to ensure a stable Indo-Pacific and world order.

In the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic, it was common to divide countries and their responses according to their political systems, with many attributing China’s success in controlling the virus to its authoritarianism. By late 2020, however, it was clear that the real dividing line wasn’t political but geographical. Regardless of whether a country is democratic or authoritarian, an island or continental, Confucian or Buddhist, communitarian or individualistic, if it is East Asian, Southeast Asian or Australasian, it has managed Covid-19 better than any European or North American country.

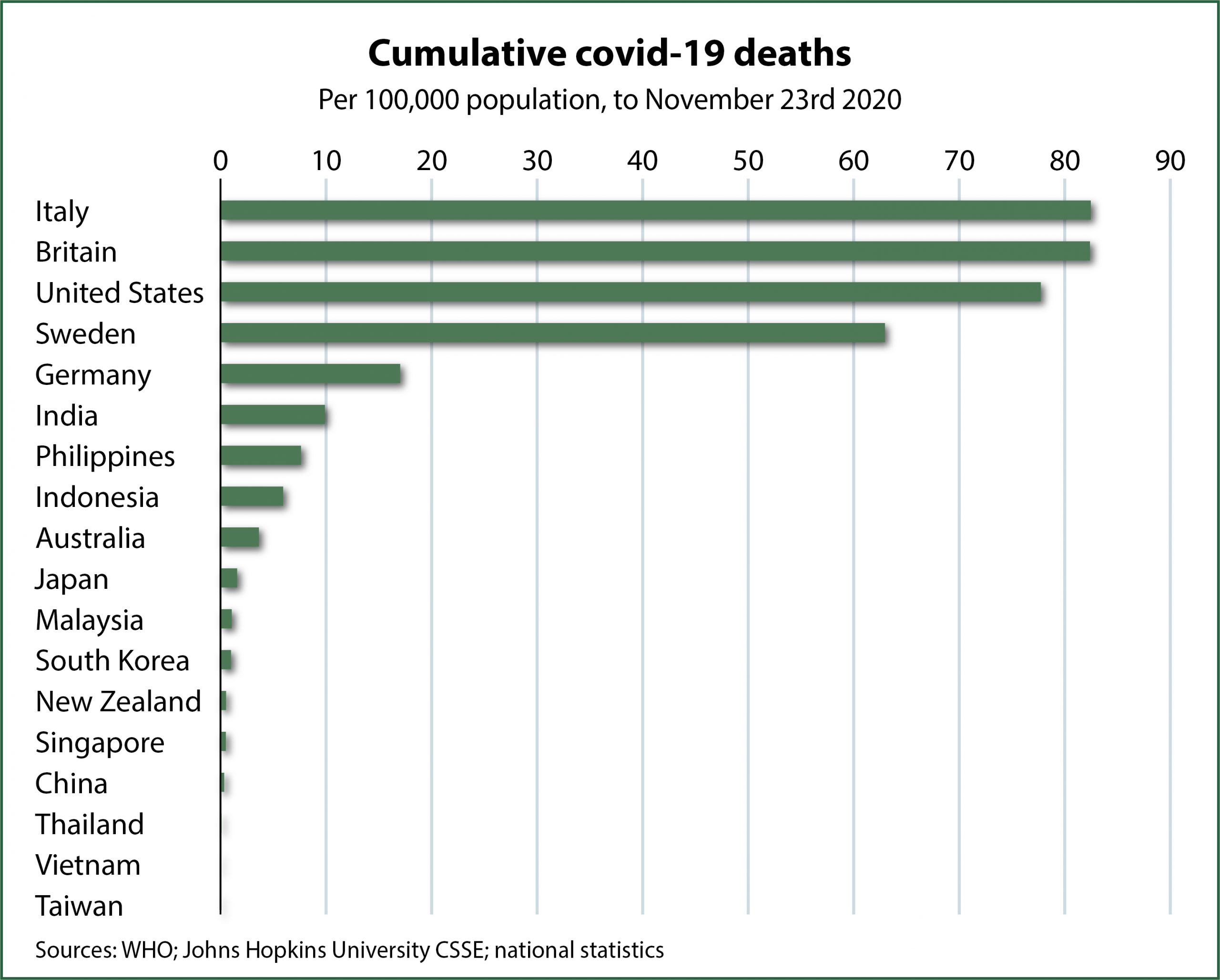

While this line is not exactly hemispheric, it is close enough to be suggestive. Even Asia’s worst performers (in public-health terms)—such as the Philippines and Indonesia—controlled the pandemic more effectively than did Europe’s biggest and wealthiest countries. Notwithstanding reasonable doubts about the quality and accuracy of the reported mortality data in the case of the Philippines (and India), the fact remains that you were much likelier to die of Covid-19 in 2020 if you were European or American than if you were Asian.

Comprehensive, interdisciplinary research is urgently needed to explain these performance differentials. Because much of our current understanding is anecdotal and insufficiently pan-regional, it is vulnerable to political exploitation and distortion. To help all countries prepare for future biological threats, several specific questions need to be explored. First is the extent to which the experience of SARS, MERS, Avian flu and other disease outbreaks in many Asian countries left a legacy of health-system preparedness and public receptiveness to anti-transmission messaging.

Clearly, some Asian countries benefited from existing structures designed to prevent outbreaks of tuberculosis, cholera, typhoid, HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases. For example, as of 2014, Japan had 48,452 public-health nurses, 7,266 of whom were employed in public-health centres where they could be mobilised quickly to assist with Covid-19 contact tracing. Although occupational definitions vary, one can compare these figures with those for England, where just 350–750 public-health nurses served 11,000 patients in 2014. (England’s population is roughly half the size of Japan’s.)

We also will need a better understanding of the effect of specific policies, such as rapidly closing borders and suspending international travel. Likewise, some countries did a much better job than others at protecting care homes and other facilities for the elderly—especially in countries (notably Japan and South Korea) with a high proportion of people over 65.

Moreover, the effectiveness of public-health communications clearly varied across countries, and it is possible that genetic differences and past programs of anti-tuberculosis vaccination may have helped limit the spread of the coronavirus in some areas. Only with rigorous empirical research will we have the information we need to prepare for future threats.

Many are also wondering what Asia’s relative success last year will mean for public policymaking and geopolitics after the pandemic. If future historians want a precise date for when the ‘Asian century’ began, they may be tempted to choose 2020, just as the US publisher Henry Luce dated the ‘American century’ from the onset of World War II.

But this particular comparison suggests that any such judgement may be premature. After all, Luce’s America was an individual superpower. Emerging victorious from the war, it would go on to claim and define its era (in competition with another superpower, the Soviet Union). The Asian century, by contrast, will feature an entire continent comprising a wide range of countries.

In other words, it’s not simply about China. To be sure, the rising new superpower has been notably successful in coping with the pandemic after its initial failures and lack of transparency. But its scope for asserting systemic superiority is circumscribed by the fact that so many other Asian countries have been equally successful without Chinese assistance.

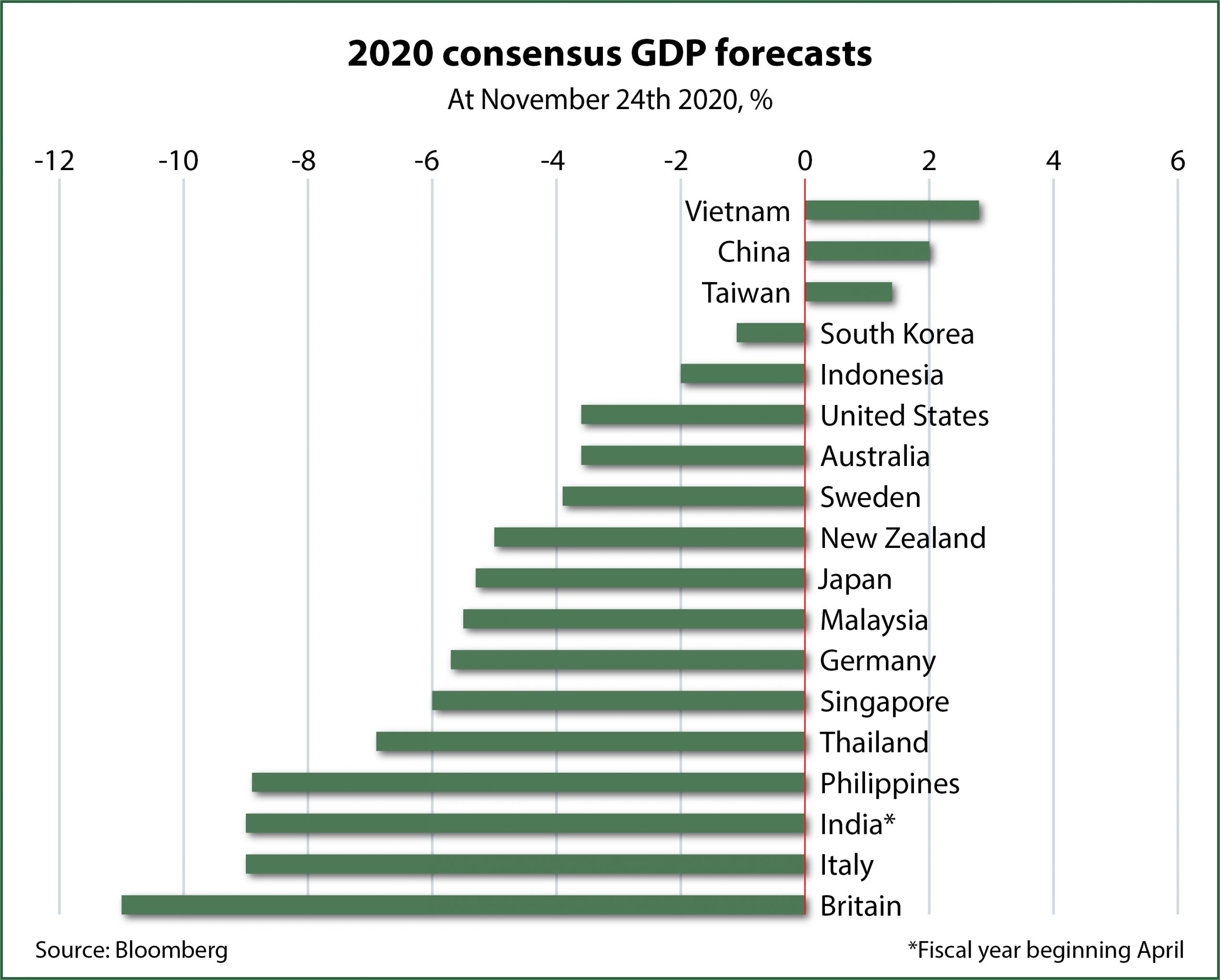

The post-war comparison also may be premature for economic reasons. Asian countries’ economic performance in 2020 didn’t match the success of their pandemic response. While Vietnam, China and Taiwan have beaten the rest of the world in terms of GDP growth, the United States hasn’t fared too badly, despite its failure to manage the virus. With forecasts pointing to a 3.6% contraction for the year, the US is in better shape than every European economy, as well as Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, the Philippines and others in Asia. The difference is largely a function of interconnectedness: compared with the US, many Asian economies are more exposed to trade and travel bans, which cut deeply into the tourism industry.

Although China’s public-health and economic outcomes have been better than the West’s in 2020, it has neither found nor really sought a political or diplomatic advantage from the crisis. If anything, China has become more aggressive towards nearby neighbours and countries like Australia. This suggests that Chinese leaders are not even trying to build an Asian network of friends and supporters.

How China approaches the issue of international debt restructurings—especially those connected with its Belt and Road Initiative—will be a key test in 2021. But, of course, the US and the rest of the West also will be tested, and on a wide range of issues, from international finance to sociopolitical stability.

It may be too soon to announce a new historical epoch. But it is not too early to start absorbing the lessons of Asia’s public-health successes.

Australia’s strategic outlook in 2021 holds both an unhappy certainty and a deep anxiety. The unhappy certainty is that China’s intent to punish us for failing to bow to its domination will continue and probably get worse.

The good news is that we now understand what needs to be done about Beijing’s bullying. The government has a tight-lipped determination to push back, as was shown this week by Treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s rejection of a $300 million takeover of the Probuild construction company by a Chinese state-owned entity.

Getting to this moment of policy clarity hasn’t been easy. It required the overturning of decades of Canberra consensus that closer engagement with China was Australia’s only path to prosperity.

With the help of Beijing’s offensive rhetoric and aggressive diplomacy, we have passed this inflection point. No federal government could reverse course and seek now to deepen our economic dependence on China.

So much for certainties. The anxiety is about how the Biden administration will approach its security interests in the Indo-Pacific. Canberra decision-makers are relieved that the unpredictable chaos of Donald Trump’s foreign policy is almost over, but Trump presided (perhaps without realising it) over a US policy establishment that shaped a bipartisan consensus on China which will last into Joe Biden’s presidency.

Yesterday a 2018 National Security Council secret document, the US strategy framework for the Indo-Pacific, was released in Washington. It advocates pushing back against China, working more closely with India, and bolstering alliances with Australia, Japan and South Korea. It also discusses doing more in Southeast Asia and the Pacific islands to help democracies. All of this can easily be adopted by Biden.

Trump pushed back more effectively than his predecessor Barack Obama against Beijing’s annexation of the South China Sea and put more priority on supporting Taipei. Trump had a positive relationship with prime ministers Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison that kept Australia prominent and appreciated in Washington and kept defence cooperation growing.

But Trump’s approach was flawed by a capricious unpredictability—for example, his ill-considered attempt to get Kim Jong-un to give up nuclear weapons on the promise of property developments and tourism in North Korea.

Canberra’s relief is that we dodged the worst of Trump’s criticism of America’s allies. We could easily have been targeted, as European allies were, for failing to pull our weight on regional security. Instead, Australia made the right call to keep Chinese companies out of our 5G network, pushed back against foreign interference in domestic politics and, belatedly, promoted a Pacific ‘step-up’.

These policy moves, along with just barely managing to get defence spending above the ‘acceptable’ NATO benchmark of 2% of GDP, buy interest and credibility in Washington.

Canberra’s anxiety about Biden reflects a concern about how he might drive American strategic policy. What if Biden reverts to an ‘Obama-lite’ strategy? Internally distracted by Covid-19 and a poisonous election year, might Biden look to placate Xi by not pressing Beijing on cyber spying, human rights abuses, Taiwan and the South China Sea and instead shape an agenda around climate, arms control and multilateral diplomacy?

Some of these approaches were features of an article Biden wrote for the authoritative Foreign Affairs journal in mid-2020. He said a priority for his first year would be to ‘organize and host a global Summit for Democracy to renew the spirit and shared purpose of the nations of the free world’.

Summits are an occasionally useful tool of foreign policy but no real substitute for practical action, a capable military, active alliances and a well-defined national agenda.

Biden’s second stated goal was to ‘equip Americans to succeed in the global economy—with a foreign policy for the middle class’. This seems to be a nod to the domestic ‘America first’ mood. Biden said that he wouldn’t enter into trade agreements ‘until we have invested in Americans’, that the ‘vast majority’ of troops must come home from the Middle East, and that military force ‘should be used only to defend US vital interests’.

Remarkably, Biden’s Foreign Affairs essay doesn’t mention Taiwan, perhaps the most immediate strategic problem he will face after the inauguration because of growing Chinese pressure threatening the island democracy.

The risk for Australia is that Biden will deliver a more elegantly expressed version of American disengagement of a type we have seen in the last four years. An ‘America first’ approach runs the risk of turning into an ‘America only’ strategy that cedes too much initiative to an angry and activist Beijing.

Australia will gain more from a United States that is encouraged to double down on its presence in the Indo-Pacific. The price for an active and engaged Washington is that we’ll have to step up our own involvement in the region and do our best to shape American policy thinking.

Biden has, for example, said that he wants to ‘jump-start a sustained, coordinated campaign with our allies’ to denuclearise North Korea. As a leading ally, Australia will need to develop some thinking about how to achieve that goal and the role we can play.

Whatever Biden’s reticence about America’s role, no global leader is better placed than Morrison to shape a more activist US engagement in the Indo-Pacific. Our management of Covid-19 and widely respected pushback against Xi’s bullying has bought Australia a privileged place at the alliance table.

Morrison should visit Washington soon after the inauguration to help shape Biden’s thinking about America’s role in the Indo-Pacific and beyond. If Biden is to develop a strategic approach that also serves Australia’s interests, we need to craft our place in that coalition effort. There is no more urgent Australian policy development task.

Key elements of this strategy should be a common response against Chinese economic coercion; a formalising of ‘Quad’ defence cooperation that also involves Japan and India; a shared condemnation of China’s dismantling of Hong Kong’s autonomy; an agreement to develop supply chains that shun Chinese forced labour; and combined planning to strengthen the defence of Taiwan.

The bedrock of our strategic credibility is our military and intelligence cooperation, more of which will be needed to make the alliance, now in its 70th year, fit for the purposes it must serve today. We must ask what more can be done to strengthen America’s military presence and cooperation in the region and what the Australian Defence Force can do to deter authoritarian military adventurism.

This will require more regional leadership from Australia than we have been comfortable delivering up until now, but the price of an engaged Washington is an activist Canberra. Biden’s strategic ambition is ours to sway.

The US government has just declassified one of its most sensitive national security documents—its 2018 strategic framework for the Indo-Pacific, which was formally classified SECRET and not for release to foreign nationals.

The full text, minus a few small redactions, was made public late on 12 January (US east coast time), having originally been cleared for publication on 5 January, prior to the turmoil in Washington.

The release of this document will be rightly overshadowed in the news cycle by the aftermath of the disgraceful domestic attack on the US Capitol, but for observers interested in the future security of the world beyond American shores, it will be of long-term interest and warrant close reading.

Long before historians can debate the Trump administration’s legacy in this vital region, this highly unusual step of fast-forward declassification—the text was not due for public release until 2043—brings an authoritative clarity to the public record.

The slightly reassuring news is that beneath President Donald Trump’s unpredictability, conceit and unilateralism, the policy professionals were striving to advance a more serious and coherent agenda.

There was a plan after all, however incomplete and insufficiently resourced its implementation.

The framework and its covering cabinet memorandum are dated February 2018, a time when the contours of strategic rivalry in the Indo-Pacific were rapidly taking shape.

Although the text would have involved negotiation among agencies, these are technically White House/National Security Council (NSC) documents. Lead authorship can be attributed to the then national security advisor, H.R. McMaster, and, in particular, to the then NSC director for Asia and later deputy national security advisor, Matt Pottinger, who was among officials to abruptly resign last week after the mob assault on the US legislature.

In a covering note explaining his advice to declassify the framework, outgoing National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien emphasises that the strategy has been all about seeking to ensure that ‘our allies and partners … can preserve and protect their sovereignty’.

This confirms that US strategic policy in the Indo-Pacific was in substantial part informed and driven by allies and partners, especially Japan, Australia and India.

Indeed, one of the strategy’s plainest successes was fulfilling the objective ‘to create a quadrilateral security framework with India, Japan, Australia, and the United States as the principal hubs’.

The American framework bears the fingerprints not only of Washington’s December 2017 National security strategy but Tokyo’s 2016 ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’ policy and Canberra’s 2017 initiatives, notably the Turnbull government’s foreign policy white paper and its early action against Chinese interference and espionage.

O’Brien properly notes this emerging convergence, and the common ground among the Indo-Pacific policies of the US, Australia, India, Japan, ASEAN, some key European partners and, increasingly, South Korea, New Zealand and Taiwan. This emerging consensus gives the lie to the Chinese claim that the Indo-Pacific is some American or Australian invention that will ‘dissipate like ocean foam’.

Without saying so, the declassified strategy appears to acknowledge that an effective American regional policy is as much about following as leading. This means steady support for allies and partners, rather than the pursuit of some shaky all-round US primacy.

It also turns out that American officials’ public line about respecting international law, regional multilateralism (such as ASEAN-centric diplomatic institutions) and the sovereign equality of states was not just rhetoric: it was what they were telling themselves as well.

Geopolitical observers worldwide, from diplomats to intelligence analysts, politicians to businesspeople, journalists to scholars, will find much else to unpack and interpret. There’s plenty to report and debate in almost every line of the 10-page document.

Contrary to concerns that the Trump administration was veering to a one-dimensional, military-led external policy, there was a clear recognition of the need for holistic engagement to bolster allies and counter China, across the full spectrum from information operations to advanced technology research and infrastructure investment.

Whether America has the capacity, coordination and will to follow through on such a total strategy is another question. The strength of the plan is also its weakness. It was an effort to exhaustively map out analytical assumptions, preferred end-states, objectives and actions, leaving it open to the criticism that it is excessively ambitious yet leaves things out.

The document is light, for instance, on anticipating the challenge of Chinese influence in the South Pacific, an indication that Canberra’s activism there is an Australian initiative, not a play to please America.

A critical reading reveals some glaring gaps between intent and reality. For example, we see an aspiration to improve relations between Japan and South Korea to put pressure on North Korea, but no sense of how this would be done.

Sometimes the bar was set so high that failure was almost assured. There are aspects where America’s privately stated ambitions—for sustained ‘primacy’, for North Korean nuclear disarmament, for international consensus against China’s harmful economic practices—were at odds with the art of the possible.

In hindsight, this bold vision for US foreign policy failed to take account of the depth of domestic division and dysfunction hampering America’s ability to advance its interests abroad.

At the same time, although it did not anticipate so staggering a shock as Covid-19, the framework’s warnings of China’s affronting assertiveness and the expansive authoritarianism of the Chinese Communist Party under Xi Jinping have proven prescient. They’ve been borne out by events, from the geopolitics of the pandemic and wolf warrior ‘diplomacy’ to the crushing of Hong Kong, intimidation of Taiwan, violent clashes with India and coercion against Australia.

Of course, the decision to release this historic document now will raise speculation as to the motive for it.

At one level, it’s a refreshing and rather radical act of transparency, aimed partly at reassuring allies and partners that, whatever its travails, America plans to double down on the Indo-Pacific.

There was likely much internal debate ahead of the decision to go public, but it was probably judged that any risk to America’s interests from showing its hand, such as the frank admission of an imperative to strengthen India as a counterbalance to China, would be outweighed by the benefits and the example of openness.

Whatever else can be said, this reduces the excuse for miscalculation, and makes more glaring by contrast the gap between what Beijing says and what it does.

There are blunt statements of the intent of ‘defending the first island chain nations, including Taiwan’, ‘denying China sustained air and sea dominance’ inside the first island chain, and continuing to dominate ‘all domains outside the first island chain’.

That said, this is not a strategy for full-blown containment extending right across the economic realm, and it does not seem to anticipate the pace or extent of decoupling since pursued both by Beijing and Washington.

The language is often defensive: not to sunder the US–China economic relationship, but rather to ‘prevent China’s industrial policies and unfair trading practices from distorting global markets and harming US competitiveness’. There’s still acknowledgement of the need to ‘cooperate with China when beneficial to US interests’, although this is so vague that it will make sense for President-elect Joe Biden’s administration to find some early specifics for cautious experiments in partnership.

Sceptical observers may well say that publishing the strategy now, amid a troubled transition, is an obvious play for policy continuity. This is in light of concerns that a Biden administration may not yet be committed to challenging China’s bid for dominance—or indeed to the idea of the Indo-Pacific, at least in its ‘free and open’ variant, as a rallying cry for regional solidarity against coercive Chinese power.

But it’s surely no bad thing to salvage the few achievements of an otherwise grim era in American foreign policy, while laying down some markers for the incoming administration.

Indeed, if the intent all along was to amplify American effectiveness by respecting and uniting allies, then a rounded 2020s evolution of the 2018 Indo-Pacific strategy will stand a significantly better chance of success under Biden than it would have under a second Trump term.

And the document articulates the fundamentals of what in Congress has become a bipartisan position on contesting China’s geopolitical powerplays, supporting allies and partners, and protecting American interests across domains ranging from military and technology to geoeconomics and information and influence.

The declassified framework will have enduring value as the beginning of a whole-of-government blueprint for handling strategic rivalry with China. If the US is serious about that long-term contest, it will not be able to choose between getting its house in order domestically and projecting power in the Indo-Pacific. It will need to do both at once.

As I have argued in my book explaining the Indo-Pacific concept, America cannot effectively compete with China if it allows Beijing hegemony over this vast region, the economic and strategic centre of gravity in a connected world.

Stable Seas recently released its third annual Maritime Security Index with one very important addition. This year, the geographic scope was expanded to include Australia for the first time. The index tells us about the current state of Australian maritime security, and, perhaps more importantly, raises questions about the future of Australian efforts to combat non-traditional maritime security challenges in its own waters and the larger region.

Maritime security is complex and multi-faceted. The Maritime Security Index brings data to bear on many aspects of these issues for the first time, providing a tool to explore trends within and the relationship between nine diverse components of maritime security across 71 states and territories in Africa, the Middle East and Asia. It focuses on some of the non-traditional security issues facing the maritime domain that often affect the daily lives of coastal communities, challenge maritime governance, and contribute to transnational crime and organised political violence.

The index can assist in visualising, quantifying and analysing the challenges and opportunities policymakers face in their maritime domains. However, we also hope that it can serve as a tool for deeper inquiry. Quantifying these complex maritime security issues is no simple task, and in attempting to do so we hope that we have given policymakers ways to engage with the analysis that open up new lines of inquiry into the current state of affairs and future policy priorities in the maritime domain.

Australia, as one might anticipate, ranks very highly across many measures of maritime security. It ranks at or very near the top of several index categories, including international cooperation, fisheries, rule of law, maritime mixed migration, and coastal welfare. These are all indications of Australia’s capacity to effectively govern its maritime domain but come as little surprise.

What may be much less intuitive are Australia’s lower scores on other aspects of maritime security, including illicit trades, piracy and armed robbery, and maritime enforcement capacity. Examining the broad factors that give rise to these results may generate productive discussions about the nature of the challenges and opportunities facing Australia.

On illicit trades, Australia sits just above the middle of the pack in the Maritime Security Index. This is primarily due to the persistent challenge of maritime drug trafficking. Australia, like many wealthy economies, is a destination market for drugs of various kinds, and some, particularly cocaine and opioids, appear to be trafficked into the country via the maritime domain at significant levels. Beyond the impacts this illicit trade may have in Australia itself, it also affects the maritime security of the states it transits through and plays a significant role in funding transnational criminal networks and armed groups in Latin America, South Asia and Southeast Asia. While attempts have been made to use Australia’s efficient, well-managed ports as entry points and vigilance against that method should be maintained, it appears that much of this trafficking tries to use isolated portions of the coast and Australian waters for drop-offs and ship-to-ship transfers.

In the area of piracy and armed robbery, Australia ranks in the bottom half of the index. Because maritime threats are inherently transnational, the index measures piracy and armed robbery not only by the presence of incidents in a country’s waters, but also by proximity to attacks in adjacent marine regions. While Australia’s own waters are free from such activity, the challenge posed by these issues in Indonesia is significant, and, as has been seen with Singapore, even states with extremely high maritime enforcement capacity can have difficulty keeping such challenges from spilling into their own waters.

What’s more, Australia’s economic prosperity is directly linked to the safety and security of maritime trade through Southeast Asia, making piracy and armed robbery in these waters an issue of core national interest. As Australia reorients its security priorities to an increasing focus on areas closer to home, maritime law enforcement capacity building with Indonesia and other regional states struggling with piracy and armed robbery could be useful in mitigating the challenge before it has the opportunity to pose a more direct threat to Australia’s economic and security interests.

Finally, and perhaps most unexpectedly, in the maritime enforcement section of the index Australia ranks 18th out of 71 countries and territories. This was a surprise, even for the Stable Seas team that developed the methodology. The Royal Australian Navy is a robust, modern force with capabilities that would be the envy of nearly any other navy within the geographic scope of the index.

However, the index weights the level of maritime enforcement capacity necessary against the size of each state’s respective maritime domain. Australia’s massive coastline and outlying islands generate an exclusive economic zone measuring roughly 8.5 million square kilometres, the largest in the Maritime Security Index’s area of study. The index takes this immense maritime domain into account as a significant challenge for projecting maritime security and governance.

The other factor that impacts Australia’s maritime enforcement score is the relatively small number of coastal patrol vessels available to the RAN and maritime law enforcement. While the RAN’s diverse assets are critical for ‘high-end’ national defence missions, they have more limited utility in combating the non-traditional maritime security challenges that are the focus of the index. These missions are likely to fall to the more limited number of the RAN’s Armidale-class patrol boats, along with the Cape-class patrol vessels operated by the Maritime Unit of the Australian Border Force. These are highly capable vessels for addressing the kind of non-traditional challenges in question, but their comparatively limited numbers still negatively affect the overall score.

There are certainly a variety of other capabilities that should be considered in a more detailed analysis of Australian maritime enforcement capacity, but the impact of limited patrol vessels on the maritime enforcement score is not detached from reality. In fact, it reflects policy conversations which are already being had in the Australian maritime security community, and the need to fill this gap has already been acknowledged by plans for procuring additional Cape-class and offshore patrol vessels.

These are exactly the kinds of conversations that Stable Seas seeks to help catalyse via the index project. With the inclusion of Australia in the scope of the project for the first time, we hope the index will be a valuable tool for members of the Australian maritime security community in identifying these nuances, advocating for resources and policy prioritisation, and building an evidence base for future efforts to ensure continued security in Australia’s maritime domain.

US President-elect Joe Biden has identified Antony Blinken as his preferred secretary of state. Challenges and opportunities abound to refashion outgoing President Donald Trump’s foreign policies that aggressively rolled back Obama-era commitments. The ‘America first’ policy saw the US pull out of the Iran nuclear deal, the Paris climate agreement, the United Nations Human Rights Council and the Trans-Pacific Partnership. The administration had begun exiting the World Health Organization, and some congressional Republicans sought to begin to dismantle the World Trade Organization. Some even challenged the value of NATO. It is no understatement that multilateralism, a centrepiece of US foreign policy since World War II, has been dramatically debilitated over the past four years.

Blinken and national security adviser nominee Jake Sullivan now face the massive task of reformulating the US’s foreign policy and national security strategy. One thing Trump’s brief tenure in office proved was that America can’t go it alone when dealing with authoritarian countries like China, Russia and their proxies. Global governance is increasingly contested and multilateral institutions such as the UN, WTO and WHO have been in direct fire in the clash of authoritarian and democratic systems.

With the incoming administration to assume power from 20 January, the naval secretary, Kenneth Braithwaite, has announced a reform of the US Navy’s 1st Fleet for the first time in more than 40 years. This follows a re-energised Quadrilateral Security Dialogue between the US, Japan, India and Australia in 2020. The US 1st Fleet will dedicate more American ships and sailors to waters off Southeast Asia and west to the Indian Ocean, including the Strait of Malacca.

Braithwaite told the US Senate’s Armed Services Committee that the new 1st Fleet ‘might be based in Singapore … [and] if not in Singapore, we’re going to look to make it more expeditionary oriented and move it across the Pacific until it is where our allies and partners see that it could best assist them as well as assist us’. In this context, the Port of Darwin may be another option, given that Darwin already hosts annual rotations of US Marines and other joint military exercises such as the biennial Pitch Black exercises hosted by the Royal Australian Air Force.

Such recent activities can tell us how current opportunities and challenges for US foreign policy renewal will affect the new administration.

China’s promise of a peaceful rise is belied by its actions, which include an extensive military build-up, growing control of global shipping lanes, and a push to secure naval access in contested maritime regions. China’s military enhancements include upgraded warships and aircraft, missile arsenals, extended nuclear reach and increased technological capability, enabling Beijing to further assert its will over global affairs. Recent sabre-rattling over Taiwan is another indicator of heightened assertiveness. China’s cyber theft of national security assets and corporate secrets also shows the lengths to which it will go to gain supremacy.

Beijing’s recent actions in the diplomatic sphere are particularly troubling. Wolf-warrior diplomacy has replaced conventional diplomatic dialogue. China penalises nations critical of it by imposing ultra-high tariffs, denying market access and using predatory economics, among other coercive tactics. China’s willingness to exploit economic interdependencies to try to impose sanctions and punish countries that oppose it in any way is now clear. The signal is to all: it is dangerous to cross China.

Yet, against this extraordinary backdrop, both Japan and Australia signed up to the China-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership on 15 November. The RCEP, a free-trade deal including 13 other Asia–Pacific nations, encompasses nearly a third of the world’s population and economic activity. That Tokyo and Canberra have signed the RCEP, even though both are in deep and unresolved conflict with Beijing, expresses the desire to continue doing business with China. India and the US are not, at this stage, signatories.

The US, Japan, Australia and India (among others) share some common challenges in their deteriorating relations with China. The Quad, which involves summits, information exchanges and some combined military drills, also contains indirect member benefits. These include improved bilateral relations among Quad nations and the possibility of future expansion. For example, the four Quad nations plus Vietnam, South Korea and New Zealand have met to discuss coordinated responses to the Covid-19 pandemic, reflecting a desire for a multilateral response. The original Quad in fact comprised Japan, the US, Canada and the European Union. The UK is a further interested party.

The building of these multilateral and bilateral relations has only further antagonised Beijing. China’s responses to the Quad, and other multilateral alliances, are worrying because both it (and Russia) are highly skilled at influencing multilateral institutions to serve their own ends, such as China’s manipulation of the WHO at the outset of the pandemic. An enhanced and coordinated naval presence in the Indo-Pacific and around the Malacca Strait is unlikely to please Beijing and a bellicose reply should be expected.

However, the Quad grouping isn’t likely to become a formal security alliance, mainly because its members have different interests in the Indo-Pacific. The US and Japan, for example, have vital concerns in the South China and East China Seas. For Australia, strategic interests focus more on the South and Western Pacific. India’s focus is more on clashes with China in the Himalayas and its interests in the Indian Ocean.

The US is now directly challenged by China in trade and investment, advanced technologies including artificial intelligence, communications infrastructure and, to an extent, militarily. While more isolated than it was before Covid-19, China is aided by Vladimir Putin’s Russia, Pakistan, Iran and North Korea. Its ‘vaccine diplomacy’ program and economic reach ensure that some dependent countries automatically vote in international forums to support China. Putin has even said that ‘liberalism has become obsolete’. China now overtly seeks reform of the global governance system to align the world more closely to Chinese Communist Party ideology. Calls to dial down rhetoric and dial up action are frequently repeated and make good sense, as it does for democracies to unify around shared interests and principles.

Looking ahead, the elephant in the US foreign policy room is not simply the People’s Republic of China, but an intensifying clash between authoritarian societies and liberal democracies that its rise represents. The Quad will need to reassure the region that it is more than just a military counterweight to China, but will apply itself to protecting the international rules-based order generally, and the economic multilateral rules-based order in particular.

A mandate for a renewed US will be to foster a more coordinated diplomatic and action-oriented effort, allowing like-minded partners to band together to defend democratic values and effective, rules-based multilateralism. The challenge is nuanced of course; no one is suggesting the road ahead will be easy.

The tiny island state of Seychelles is rethinking its future in the light of the Covid-19 pandemic and the first democratic change in its ruling party in 43 years.

Charting a new way forward for the country, increasing food security and building new industries based on the blue economy and knowledge are priorities for the new government of Wavel Ramkalawan, former opposition leader and now president. It will involve assistance from partners such as India, China and Japan, and it won’t be an easy task.

Although Seychelles has long experience in balancing competing external interests, increased geostrategic competition in the Indian Ocean may make it harder to secure the foreign investment it urgently needs to rebuild after the severe economic impacts of the pandemic.

When it achieved independence from Britain in 1976, the new country was quickly drawn into wider global networks. Its position as an ‘unsinkable aircraft carrier’ in the western Indian Ocean made it attractive to the big powers.

A socialist coup soon after independence propelled it towards the Soviet bloc, but, even then, Seychelles trod a fine line between opposing factions, and the US continued to operate a satellite tracking station on the main island of Mahé.

A long runway built in 1971 helped establish international tourism, which soon became the main pillar of the economy.

With half of its forests protected from development and its sandy beaches and the surrounding ocean teeming with fish, the country was promoted as a tropical paradise.

Other mainstays included fish processing and an offshore finance facility, which led to an unwanted reputation for money laundering and illegal transactions.

Over the past decade, the economy has been reasonably sound. The World Bank designated Seychelles as a high-income country. Until recently, the nation had credible reserves of foreign exchange, and it scores well on measures of health, education and social welfare.

From the start of this century, there has been a construction boom. Even 10 years ago, the roads were relatively empty; now, daily rush hours are commonplace.

But the Covid-19 epidemic caused international flights to be cancelled and prompted a domestic lockdown. Seychelles has recorded very few cases of coronavirus, but that has come at the cost of a booming tourist industry. Inflows of foreign exchange were drastically reduced, the exchange rate fell, prices rose and there were shortages of some goods. Many businesses were caught in debt traps.

Elections in October 2020 led to the comprehensive defeat of the party that had held power for more than four decades. The priority for Ramkalawan and his government is to work towards a new future. To revive the economy there must be more tourists, although that will risk a rise in the number of infections.

In the longer term, the economy must diversify, make smarter use of people’s skills and include more knowledge-based occupations. This will require a revolution in broadband capacity and an upgraded program of ICT training and education.

Digital capability upgrades can only be achieved with the support of international partners. But, as the past has shown, there’s invariably a price to be paid for such assistance, whether through security concessions or votes in the United Nations.

Developing the blue economy may also help. Seychelles made an early start in promoting the concept of sustainable seafood production and blue energy, but there have been few tangible results.

Tapping the energy reserves of tides and currents is still far from being realised, and little has been done to see what can be grown in the sea itself. Considerable investment is needed for research and development, which is beyond the reach of a small nation. Partners with access to more resources are essential if oceanic opportunities are to be realised.

Comparable challenges in neighbouring island states in the western Indian Ocean (Mauritius, Réunion, Comoros) should encourage a regional approach that produces economies of scale in investment and governance. Making the blue economy work is also of interest to other small island states in the Pacific and Caribbean. Ideas and experience can be shared to the benefit of all.

Another vulnerability highlighted in recent months is Seychelles’ heavy dependence on food imports. It’s self-sufficient in fish and eggs but imports up to 90% of other foods. Supply lines can’t be guaranteed, and increasing locally sourced supplies is imperative.

The previous government identified pork, poultry and a range of vegetables as candidates for greater production, ideally leading to self-sufficiency. More also needs to be done to ensure that food grown locally is organic.

Securing external assistance to aid economic recovery will require careful diplomacy. Seychelles has always attracted the interest of big powers—first France and Britain as colonial powers, then the US and the Soviet Union during the Cold War, and more recently India and China.

There are close relations with the United Arab Emirates, and Japan has recently opened a new embassy. Meanwhile, the US, from its strongholds in Diego Garcia and Djibouti, maintains a watching brief.

The country has long benefited from loans, grants and infrastructure investment. Recovery won’t be possible without further support, but it will be a challenge to accept funding from one source without upsetting another. If, for example, India revives its interest in a naval base on the outer island of Assumption, the strategic concerns of China will need to be addressed.

It’s no coincidence that, in 2018, just a few months after the former president, Danny Faure, went on a state visit to India, he was then invited to meet President Xi Jinping in Beijing. No details were released about what was discussed, but some kind of balancing concession will surely have been on the agenda.

‘A friend of all and an enemy of none’ is a term often used to sum up the nation’s diplomacy. This has been tested before, but perhaps not at any time more than now.

This post is part of an ASPI research project on the vulnerability of Indo-Pacific island states in the age of Covid-19 being undertaken with the support of the Embassy of Japan in Australia.