Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

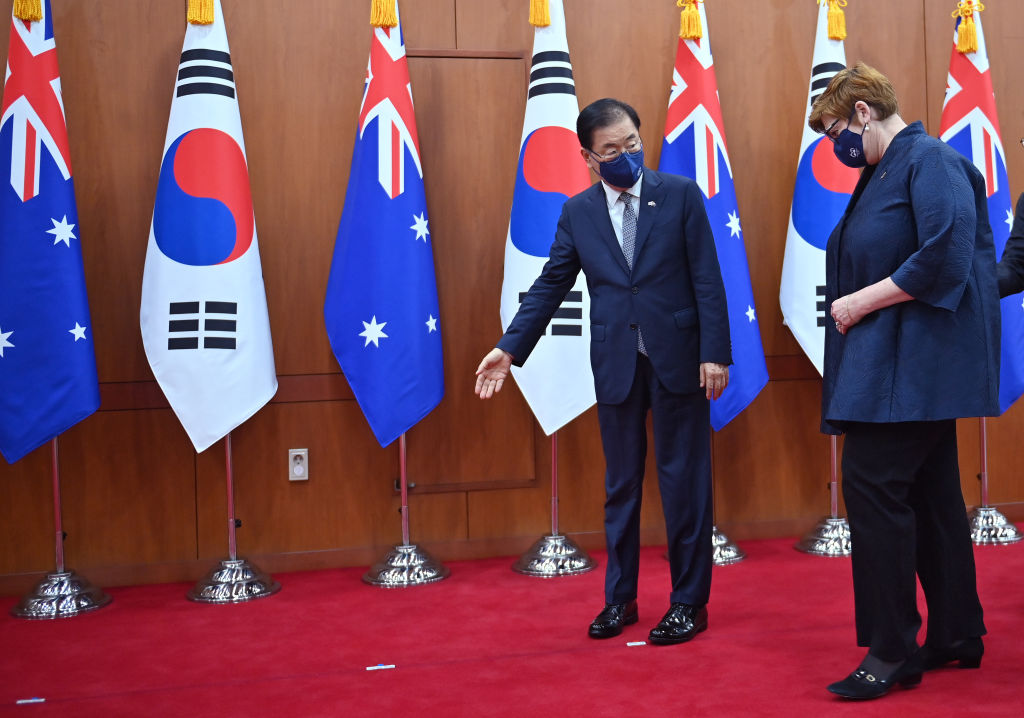

As the Australia–Japan security relationship continues to strengthen, there’s concern among the South Korean security community that that may come at the expense of their country’s own interests.

Security cooperation between South Korea and Australia has become closer over the past decade, reflected in the holding of joint maritime military exercise Haedori–Wallaby since 2012 and the biennial 2+2 meeting of foreign and defence ministers since 2013. Australia has also occasionally participated in the US–Korea amphibious exercise SsangYong, the anti-biological warfare exercise Able Response, and the Ulchi Freedom Guardian exercise.

The speed with which security cooperation has been developing between South Korea and Australia, however, doesn’t match the development of cooperation between Australia and Japan. The security relationship between Australia and Japan has been enhanced to the point that they’re often called ‘quasi allies’. Consequently, there’s a view in Seoul that Canberra is more supportive of Japan’s security posture than of Korea’s.

Concerns peaked after Australian prime minister Tony Abbott remarked in October 2013 that Japan was ‘Australia’s best friend in Asia’. Then, the conservative government in Seoul had assessed that the North Korean regime would soon collapse. South Korea hoped to rule out any possibility that Japan would interfere if a contingency should arise on the peninsula. South Korean concerns about any such intervention were founded on the United Nations Korea Command—Rear being located in Japan.

This gives the UN HQ legal grounds to dispatch UN troops from Japan to Korea in the event of a Korean contingency. Another (mis)perception in South Korea that has hindered security cooperation between Seoul and Canberra has been Australian support for the efforts of the US and Japan to construct a missile-defence system in the region.

In 2017, tensions heightened between Pyongyang and Washington when North Korea threatened to test-fire an intercontinental ballistic missile towards the US mainland. Australia’s prime minister Malcolm Turnbull announced that Australia would invoke its alliance treaty to defend the US if that eventuated.

Australia’s position wasn’t appreciated by the South Korean government, which saw these remarks as escalatory and unnecessarily provocative eye-for-an-eye exchanges. It feared that they’d damage South Korea’s efforts to mitigate tension between North Korea and the US.

In 2020, Japan and Australia agreed to sign a reciprocal access agreement, a bilateral arrangement that would enable Australia to dispatch a large number of military personnel to Japan for exercises on Japanese soil.

By 2021, Japan had enhanced its role as a key node of the US-led security network in East Asia and beyond. It achieved this by enhancing its security cooperation with Great Britain and France, and in May conducted a military exercise in Japan with France, the US and Australia.

Given the already very close security relationship between Japan and Australia, some in the South Korean security elite are concerned that their enhanced, and expanding, security cooperation as part of the US-led network might result in Japan emerging as a regional hub of that alliance network.

While South Korea has expanded its security cooperation in the region and has joined various multilateral military exercises in the Pacific and Indian Oceans with different groups of states, it has two major concerns.

South Korea doesn’t feel comfortable with Japan taking a central role in exercises in the East Sea or Northeast Asia and remains concerned about its diminished security status and the possibility of being ‘demoted’ in relation to Japan in the northern axis of the US-led security network.

South Korea also remains concerned that participation in such exercises would risk unnecessarily provoking China, complicating cooperation between Seoul and Beijing on North Korea.

If Australia were perceived by South Korea as becoming too deeply engaged in security cooperation with Japan, it would again raise suspicion that Australia is more supportive of Japan than of South Korea.

To maintain its position within the US-led security network, South Korea needs to be more active in joining military exercises organised by the US. One way to enhance the Korea–Australia bilateral relationship would be for Korea to join the Australia-led exercises in the Pacific along with the US, rather than the Japan-led exercises in Northeast Asia.

In this context, it’s worth noting South Korea’s participation in the Talisman Sabre military exercise involving Australia and the US in 2021. While, strategically, Korea has been hesitant to join military exercises that might be seen as targeting China, it has good reasons to participate in them from an operational perspective, especially to enhance interoperability.

As it seeks to enhance its security cooperation with Australia, whether bilaterally or more broadly, South Korea must walk a fine line.

‘When bad men combine, the good must associate; else they will fall, one by one, an unpitied sacrifice in a contemptible struggle.’

— Edmund Burke, ‘Thoughts on the cause of present discontents’, 1770

The only surprising thing about AUKUS is that it has taken so long to be formalised. For more than a century, Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States have worked together to protect shared values and improve the security and wellbeing of people around the world. We have been natural allies and we have stood together in the face of totalitarian coercion, oppression and force.

We must never forget that freedom and respect for the rights of the individual are not universally accepted as a global good. The intolerance and oppression of totalitarian power were not eliminated following the defeat of Nazi Germany, the collapse of the Soviet Union or the disintegration of the Islamic State’s so-called caliphate.

The 2020 defence strategic update makes it clear that Australia’s strategic environment is changing as both military and grey-zone threats evolve at unprecedented rates. Democratic nations are witnessing the most consequential strategic realignment since World War II and are increasing their collaboration in response.

AUKUS has been described as ‘epoch-making’ and ‘the biggest strategic step Australia has taken in generations’. Given the headlines and commentary, however, it will come as a surprise to many that AUKUS is not predominantly about submarines.

Certainly, eight nuclear-powered submarines for the Royal Australian Navy will be a potent and effective deterrent that will contribute to the maintenance of security within the established global norms that have benefited all nations in the Indo-Pacific over past decades. But as one commentator has rightly pointed out, ‘the bigger picture is getting lost in a sea of naval analysis’.

The real value of this partnership lies in the joint development of capabilities and the deeper integration of defence-related science and technology, industrial bases and, importantly, supply chains.

This new trilateral security partnership will work towards making each partner more capable and more resilient. AUKUS complements, rather than competes with, regional partnerships such as the Quad and intelligence-sharing arrangements such as the Five Eyes.

Critics of the government have raised questions about what AUKUS will mean for Australia’s capacity to make sovereign decisions. They point to nuclear submarines to suggest that such technological dependence on the US will diminish Australia’s sovereign ability to act in its national interest.

Perhaps these critics are unaware of the facts, but more likely they have embraced historical amnesia for the sake of short-term political gain and are choosing to ignore the record of partnership between Australia, the US and the UK. An exemplar is air combat capability.

During World War II, Australia’s only locally designed and manufactured fighter, the Boomerang, was powered by a US-designed Pratt & Whitney engine. Royal Australian Air Force pilots stood a better chance of survival and victory in the Pacific theatre when flying the British Spitfire or the American P-40 Kittyhawk. The P-51 Mustang, which provided Australia’s air combat capability through until the Korean War, was a US design powered by the UK’s Rolls Royce Merlin engine. In today’s RAAF, the F-35 can hardly be considered to be Australian-designed or -controlled technology, nor can the F/A-18F Super Hornet, P-8A Poseidon and many others. The Loyal Wingman remotely piloted aircraft is as close as we get to Australian-owned air combat technology, but even then, Boeing, a US company, is the manufacturer.

Whether at the tactical, technical or strategic level, history shows that the government can and does make sovereign decisions in Australia’s national interests despite a high level of technological reliance on the US and UK.

During Operation Slipper and related deployments to the Middle East, Australia made its own decisions on rules of engagement even though Australian forces were operating alongside the US and other partners. Australia made the unilateral decision to enhance the capability of its US-made CH-47D helicopters prior to sending them to Afghanistan. After buying the US Navy’s F/A-18 Hornet, we chose to integrate the UK ASRAAM in preference to the standard US AIM-9 short-range air-to-air missile.

The history between the three parties in AUKUS validates this observation of independent action more broadly. In 1958, Britain acquired nuclear technology for its submarines from the Americans. Shortly thereafter, the US requested that Britain commit troops to the Vietnam War. However, UK Prime Minister Wilson refused, instead offering in-principle support for the war but not a military commitment. During that period, Australia operated French Mirage III fighters and British Oberon-class submarines but, unlike the UK, decided that the national interest was served by supporting South Vietnam. The UK and Australia have both remained committed and reliable allies of the United States, while maintaining sovereignty over the deployment and use of military capability.

To understand why AUKUS is so important, you only have to consider the lessons of Covid-19 around supply-chain resilience and the assessment of threat in the defence strategic update, which calls for Australia to be capable to shape our region, deter aggression and respond with military force if required.

The ability to deter aggression in our region will be enhanced by the agreement to provide the Australian Defence Force with a range of precision-guided missiles, particularly long-range strike weapons that can hold an adversary at risk. Maintaining regional security, however, requires the ability not just to deploy military force when required, but to sustain operations. This requires resilient supply chains, which will be enhanced by the decision to accelerate the manufacture of precision-guided missiles in Australia.

Returning to air combat for an example, AMRAAM is the key air-to-air missiles currently certified for use on aircraft operated by Australia, the US and other partners such as Japan, South Korea and Singapore. The US also has commitments to supply AMRAAM to partners in Europe and the Middle East. The capacity to replenish war stocks will therefore be limited in the event of a major or concurrent conflict, and an alternate manufacturing base will be key to ensuring resilient supply chains in any near-term conflict. AUKUS should underpin an agreement for Australia to develop the local capability in partnership with the AMRAAM manufacturer Raytheon to make and supply the missiles for our own and our allies’ use.

AUKUS does not make Australia captive to a foreign agenda. Instead, it opens doors to enhanced collaboration that will build collective capability and resilience, enhancing Australia’s ability to partner with like-minded nations to deter threats and contribute to stability and security in the Indo-Pacific.

So we’ve gone all in. The trend lines have been there for a while, but as several commentators have pointed out already, the awkwardly named AUKUS is a step change in the level of commitment by Australia to the United States.

The ‘forever partnership’ binds us more closely to America at a time when there was starting to be debate, especially among conservative thinkers, about the need for a more independent Australian capability. That debate wouldn’t have passed unnoticed in Washington. Given the apparent willingness of the US to share exceptionally closely held technology, indications are that it is a very deliberate choice on the part of the United States.

If the strategic rationale of AUKUS is to build capability in the Indo-Pacific and offset China, the tripartite nature of the agreement bears further consideration. Despite cultural affinities and longstanding ties—including a separate shipbuilding program for Australia’s Hunter-class frigates—the United Kingdom is not a natural partner in the Indo-Pacific. That raises the question of whether the US is seeking to bolster the UK’s strategic weight and outlook, at a time when it has retreated back across the Channel. If so, AUKUS may be stretched thin, seeking to cover many foreign policy and strategic objectives across three democracies weakened at home.

That stretch in the AUKUS arrangement is reflected in the amount of white space in and around the agreement. Of course, that’s not unexpected—new initiatives typically deepen in complexity over time. But it’s easy to underestimate the amount of effort needed to rebase Australia’s own capabilities, especially if, as many argue, urgency in the face of a rising China was one of the factors driving the decision to dump the French submarine contract. On the submarines alone, the Australian government has given itself 18 months to figure out the what and how of the new program.

That’s going to be tough: it’s a complex endeavour. The tasks include negotiating the termination of current arrangements, reconfiguring infrastructure, and recruiting and retaining the skills needed for a new, complex and dangerous industry.

More broadly, the White House statement reflects a pressing need to uplift not simply Australia’s military capability—a major task in itself—but its technological capability as well. The technology uplift will depend heavily on the very sectors the government has neglected or actively eroded over the past few years. It would be surprising if American analysts of Australia haven’t flagged this as a concern, both in assessing our role as an ally and in shaping this new initiative. While AUKUS has been cast as a defence initiative, it will not succeed unless the government engages civil society and civilian capability more broadly.

As importantly, the government will need to improve its own administrative and governance capabilities. Australian government prioritisation, procurement and contractual processes and management have lost their discipline and rigour. A more mature and knowledgeable relationship with industry is needed. That in turn implies a re-professionalisation of a public sector derided by its own ministers.

AUKUS—as proffered thus far—is about cementing old ties and shoring up defences against a rising revisionist power. The statements, the language, don’t offer a vision of the sort of future that we, the United States and the United Kingdom want to see in the region, or globally.

AUKUS also seems unwarrantedly exclusionary at a time when both Australia and the US need to build more inclusionary structures and processes in the region. Work will be needed to make existing and nascent structures, such as Five Eyes and the Quad, complementary to the new arrangement. Additional effort will be needed to engage nations such as Indonesia, which will now be contemplating a more muscular southern neighbour.

In short, what the agreement most lacks is a strategy. Pretty words and a bundle of exclusive nuclear technologies for naval propulsion do not fundamentally change the power balances of the Indo-Pacific. And that’s assuming we can digest the rich platter now set before us. It’s yet to be seen whether the price put to the Biden administration by the Morrison government for cementing the cracks and reining in uncertainty is too steep—for Australia, as much as for the United States.

In 1966, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson wrote to his Australian counterpart Harold Holt to explain that Britain would wind back its military deployments in the Asia–Pacific, reducing its presence ‘east of Suez’. Wilson told Holt that the cost of these deployments had become ‘a burden which we cannot afford’ and ‘out of scale’ with Britain’s new, Europe-centred foreign policy.

Five decades later, Prime Minister Boris Johnson appears to have overturned this east-of-Suez posture by entering into the new AUKUS defence pact. In so doing, he has committed to the firmest initiative yet to cement his post-Brexit vision of a ‘Global Britain’.

However, the full details of the trilateral agreement remain unclear. Whether AUKUS really ends up returning Britain to the Asia–Pacific (or Indo-Pacific, in the current parlance) will be the biggest indicator yet of whether Global Britain is a real objective or merely a rhetorical placebo to soothe angst over Britain’s post-Brexit future.

So far, the most tangible initiatives towards Global Britain have been altering foreign aid commitments, contributing to international Covid-19 vaccination efforts, and restructuring the UK’s foreign office. The most coherent articulation of Global Britain came in March in the form of the government’s integrated review of defence, development and foreign policy.

However, the true military dimension of Global Britain has thus far been ambiguous. Care has been taken to ensure the Global Britain program isn’t seen as a plan to project power against a bellicose China. Rather, it has been presented to the world as a plan for a British international role less buttressed by the European Union. The AUKUS commitment, however, will now leave little doubt that Johnson’s vision of a Global Britain also comprises strategic posturing against Chinese aggression in the Indo-Pacific.

The headline announcement of AUKUS is the exchange of technological knowledge to ensure Australia can acquire nuclear-powered submarines. It will ostensibly facilitate greater information sharing for other critical technologies as well, such as artificial intelligence, cyber capabilities and quantum computing. Yet what exactly that additional sharing of information will look like remains unexplained. It’s not even clear if AUKUS will be supported by a formal treaty.

Australia, the UK and the US already have an incredibly close partnership, with the Five Eyes grouping providing unmatched access to each other’s military and intelligence secrets. They also already have mutual access to one another’s training grounds, space platforms and research programs and are constantly jointly developing new capabilities.

So, beyond submarine technology, which arguably could have been shared previously, what exactly does Britain achieve by entering into the AUKUS pact? The optics of committing to a new trilateral agreement doubtless send a powerful diplomatic signal to China, Indo-Pacific countries and Britain’s partners about the importance of the region’s security to Britain’s foreign policy. Yet, more will be needed to ensure AUKUS is not just a high-production exercise in diplomatic theatre.

For Johnson to convince the UK’s allies and partners—as well as China—that AUKUS really is a concrete pillar of his Global Britain vision, the UK will soon need to establish a more fixed presence in the Indo-Pacific under the auspices of AUKUS. That could include basing British nuclear submarines in Australia or embedding more of Britain’s own forces in the region akin to the American’s deployment of marines to Darwin.

China will probably move swiftly to test the resolve of AUKUS, hoping to prove that it is no more than a paper tiger by forcing at least one of the three countries to lose face and limit its commitment. Such a test could come in the form of economic sanctions, cyber warfare, or even military manoeuvres. As the one AUKUS partner not resident in the Indo-Pacific region, the UK is the obvious candidate for a first challenge to the partnership. Should it falter in practically reinforcing its rhetorical support for AUKUS, the credibility of the UK’s Global Britain agenda will also be at stake.

In response to Britain’s 1960s proposal of withdrawing from east of Suez, Holt implored Wilson to reconsider, arguing that the ‘strength, stability and peaceful progress’ of the region needed the ‘moral, material and even military help’ of the United Kingdom. To not provide this assistance, Holt wrote, would be ‘an error which history would condemn’. However, the cost of a UK military presence in the region proved too great for Wilson and his decision arguably marked the end of the last semblances of the British Empire—the previous ‘global’ Britain. Johnson must now similarly decide whether the UK will carry the cost of upholding peace in the Indo-Pacific. This time around it may be a far greater burden.

Last Friday, Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga announced that he wouldn’t be contesting the ruling Liberal Democratic Party’s presidential election at the end of September. In doing so, he effectively signalled his intention to resign as Japan’s top leader after only a year in office.

The decision was unexpected, though not entirely surprising. A botched national response to the Covid-19 pandemic, and the almost routine scandals that seem to implicate the Japanese prime minister’s office, have resulted in increasingly poor polling for Suga’s government. Despite several bold and perhaps desperate moves to shore up his position in the LDP, Suga was eventually left with no option but to step aside.

With Shinzo Abe at the helm for most of the past decade, Australia could be forgiven for becoming accustomed to stability at the top of Japanese politics. But the departure of two prime ministers now in less than a year is worrying. A return to a pattern of frequent leadership turnover risks dulling Japan’s competitive edge in the Indo-Pacific. That effect could be magnified by persistent shortcomings in US regional strategy—gaps that Japan has filled for much of the recent past.

In fact, with the US largely absent from key regional forums in recent years, Japan under Abe came to be widely considered the de facto leader of the liberal order in the Indo-Pacific. Abe’s political longevity, adroit alliance management and strategic acumen ensured that the worst excesses of the US during Donald Trump’s administration didn’t critically undermine the regional order. Indeed, Tokyo was an indispensable partner for Canberra in getting the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership over the line, and Japan’s quiet but effective capacity-building, infrastructure and health initiatives have helped build stability in Southeast Asia.

Until the long-promised US rebalance to Asia truly materialises, if it ever does, the fact is Australia still needs a Japan capable of playing a major leadership role in the Indo-Pacific.

As my colleagues and I argue in our report Correcting the course, the approach taken by Joe Biden’s administration in the Indo-Pacific so far has lacked the sort of focus and urgency required to compete for regional influence. Questions loom over the administration’s capacity or willingness to develop a comprehensive regional trade strategy, for example. And repeat visits by cabinet officials to Singapore and Vietnam are no substitute for robust engagement with Southeast Asia more broadly.

These, unfortunately, are not new problems. And it’s therefore no coincidence that it is in these key areas that Japan’s regional activism has been of greatest value to Australia over the past decade—particularly since 2016. The risk now, however, is that persistent shortcomings in US Indo-Pacific strategy will compound with a sustained period of political bloodletting in Tokyo, with potential consequences for Japan’s regional strategy.

As Abe’s right-hand man, Suga was widely expected to ensure foreign policy continuity. And on that score at least, his tenure has been a success. Suga sustained Japan’s understated engagement in Southeast Asia and oversaw a notable hardening in Japan’s public posture on China’s coercive behaviour, particularly in the East China Sea and around Taiwan.

Importantly, Suga also doubled down on Australia–Japan ties. Ambassador Shingo Yamagami’s unprecedented public profile since his arrival in Canberra in January neatly demonstrates those efforts. It was no coincidence that Prime Minister Scott Morrison was the first foreign leader to visit Suga in Tokyo. And notwithstanding glacial progress on the reciprocal access agreement, new legal and operational accords have been struck to deepen engagement between the Australian and Japanese defence forces.

Even so, many predicted that Suga would serve only in an interim, ‘caretaker’ capacity, before making way for a more durable, empowered leader. But his departure nevertheless renews questions over whether the eight years of political stability at home and effective leadership abroad under Abe were an exception to the rule. There is no guarantee that Suga will not become the first in a new succession of ‘revolving door’ prime ministers.

A change of leader is unlikely to see Japan absent itself from the region in the same manner as America. Nor will it markedly change the overall trajectory of Japan’s regional strategy. But more frequent rotations of personnel through the Kantei and top foreign policy positions could, over time, dull Japan’s edge in regional competition with China and stall developments in key relationships, including that with Australia. It will not be a positive development if ministers who have paid particular attention to Australia, such as Defence Minister Kishi Nobuo, are replaced.

Suga’s successor will also assume power only months ahead of a general election. Experts have pointed out that although the government will almost certainly remain in power, a reduced LDP majority will make it harder to pursue ambitious defence and foreign policy goals, such as acquiring pre-emptive long-range strike capabilities. Tighter political margins may hamper the sorts of self-strengthening initiatives that enhance Japan’s strategic value to partners like Australia.

The challenges that awaited Suga as he entered office—a worsening public health crisis, perennial economic stagnation, acute demographic decline—will also confront his successor. Most of these issues are of greater public concern than Japan’s activities abroad.

Fortunately, there is a silver lining for Australia. Suga was generally regarded as more domestically oriented than his predecessor, but his replacement may be someone with greater experience and interest in foreign policy. And they may already be known to their Australian counterparts.

Two candidates stand out in this regard. The first, Administrative Reform Minister Taro Kono, is widely considered the frontrunner to succeed Suga. He served as defence and foreign minister in different Abe cabinets, and is a vocal advocate for intelligence-sharing between Japan and the Five Eyes nations, and of advancing defence cooperation with Australia. Kono was outspoken on the threats posed by China before the government’s change in tone and is known for straight talking on tricky issues in the US–Japan alliance. That quality would also be a valuable asset in navigating complex upgrades to the Australia–Japan relationship, such as those proposed by Ambassador Yamagami.

Fumio Kishida is also well known to Australia, having served as foreign minister between 2012 and 2017. Though considered less hawkish on China than his competitors for Japan’s top job, Kishida has nevertheless stressed the importance of maintaining the trajectory of Japan’s Indo-Pacific strategy (including its partnership with Australia) and of strengthening Japan’s defence capabilities to adapt to the deteriorating regional strategic environment.

It is in those interests that Japan’s regional partners will hope that whoever emerges as the next prime minister will occupy the Kantei for some time. But until that is assured, and until Washington gets its act together in the Indo-Pacific, Australia may yet face uncomfortable questions over the future of the leadership of the regional order.

Australia’s strategic value to Japan can be summed up in three points. Australia is Japan’s partner in bearing the torch of democracy, a quasi-ally with which Japan will work to maintain the Indo-Pacific as a free and open region, and a force multiplier for Japan and its alliance network. Japan’s strategic value to Australia can be described in the same way.

In 2049, the Chinese Communist Party will celebrate the centenary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Until then, it will continue to build its economic and military strength, seeking to expand its dominance in the Indo-Pacific. As this trend accelerates, Australia’s strategic value to Japan is also destined to increase.

Australia has never been unimportant to Japan—the trade relationship dates back to 1957. Australia’s supply of iron ore, bauxite, coking coal and natural gas was the lifeblood for Japan’s rapid economic growth. They say Australia is a lucky country endowed with natural resources. Japan was no less lucky to have Australia as a key trading partner.

Early in the 1980s, Tokyo and Canberra together launched the Asia–Pacific Economic Cooperation forum, creating the framework for the economic growth of ASEAN nations. Since then, a relationship focused on trade has evolved into one providing a vision for the region’s future. Economics and trade have been the alpha and omega of the Australia–Japan relationship. In recent years this has begun to change.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s administration in Japan, from 2012 to 2020, deepened and broadened the strategic nature of the Australia–Japan relationship. It also gave a strategic dimension to the trade relationship. Abe dealt with three Australian prime ministers, all of whom made the relationship geopolitically relevant.

One outstanding Abe achievement was bringing to life the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue involving the United States, Japan, Australia and India. At the end of December 2012, as he began his second term as prime minister, Abe wrote an article for Project Syndicate, ‘Asia’s democratic security diamond’, arguing that Indo-Pacific security should be the responsibility of a diamond formed by Australia, India, Japan and the US. Abe decided that was too much like blowing his own trumpet and he has not used the term ‘diamond’ since. Whatever one calls it, the Quad is the realisation of Abe’s vision.

It is too early to discuss how the Quad should be institutionalised and whether it should expand its membership. What is important is that the four countries’ leaders have agreed to foster the habit of cooperation. Seeds have been planted that will grow into the future. The focus is solely on security, on working together to achieve a free and open Indo-Pacific.

Abe broadened the interpretation of Japan’s constitution, which had become too rigid and outdated, and significantly expanded the scope of joint action between allied forces and the Japan Self-Defence Forces.

As an example, if a Royal Australian Navy ship is in the waters around Japan or a Royal Australian Air Force aircraft is flying near Japan’s airspace, it will be under the protection of the Japan Self-Defence Forces. In fact, US ships and aircraft routinely operate under the protection of the JSDF.

Compared with the Australian military’s history of joint operations with the US military, as in Korea and Vietnam, the changes that have finally taken place in Japan are modest. But the Chinese People’s Liberation Army cannot underestimate the significance of Japan and its partners becoming force multipliers for each other.

Australia is both a Pacific and an Indian Ocean power, and that is where its unique value lies. Japan and Australia, along with the US and India, will continue to play a role in making the Indo-Pacific a free and open place. Japan and Australia are now partners raising the torch of democracy.

When Australia and Japan signed a trade agreement in 1957, the Japanese prime minister was Nobusuke Kishi. By an accident of history, his grandson, Shinzo Abe, eventually succeeded in forging the most advanced form of free trade agreement, an economic partnership agreement, between Australia and Japan. In addition, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull and Abe rescued the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (now known as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, or CPTPP) from the brink of death when US President Donald Trump dealt it a blow.

Any country that maintains state control and political party involvement in business management does not deserve to be part of the CPTPP. By building on their economic partnership agreement, Japan and Australia have created a free, transparent, rules-based economic system that spans the Pacific, using the trust fostered by economics and trade as a lever.

The fact that the UK is about to join the CPTPP, and that the CPTPP has provided the impetus for the EU and Japan to establish their economic partnership agreement, also demonstrates that Japan and Australia have become partners in sharing the responsibility for maintaining a democratic and free economic system on a global scale.

Both Australia and Japan have a track record of fostering democracy while respecting social pluralism. Both Tokyo and Canberra know that their democracies will never be complete.

To abandon democracy and become Leninist is unthinkable either in Australia or in Japan. In China, there’s a risk that the Chinese Communist Party’s stranglehold will collapse and the system will be replaced by something else. Both Australians and Japanese believe in the values of democracy. Even if democracy is on the wane elsewhere, they are willing to raise the flag of democracy. And there is the Quad, with Japan and Australia as its northern and southern pillars.

Australia, as seen from Tokyo, is a pillar of democracy, perhaps more so than Australians realise. It’s not for nothing that Japan, with its rapid growth, has Australia so close at hand. It’s a blessing for the whole world that Japan and Australia can now work together as dependable partners in uncertain times.

It’s a rare thing for an alliance to last as long as the ANZUS Treaty, signed 70 years ago today. A Brookings Institution study in 2010 reviewed 63 major alliances over the past 500 years and found only 10 lasted more than 40 years. These included NATO, ANZUS and the US–Japan treaty.

The alliance between Australia and the United States survives because it suits both countries’ interests. Don’t be fooled by the usual rhetoric about mateship and standing shoulder to shoulder. Strong alliances are based on calculations of interest and mutual usefulness.

The clearest lesson to come from the debacle in Afghanistan is that the US has no interest these days in helping those that are incapable or uninterested in helping themselves. For Taiwan, Japan, South Korea and Australia, the message is the same: lift your defence game.

The NATO benchmark for alliance adequacy used to be to spend 2% of GDP on defence. After years of pressure from Washington, only 10 of the 29 NATO countries with armed forces currently meet that standard.

Australia just gets over that budget line. Given the enormous challenges a belligerent China presents to the Asia–Pacific, we desperately need to rethink our defence posture.

For Australia the alliance remains vital. We could double defence spending and get nowhere near the deterrent power that the US presence in Asia provides. The challenge is to sustain American engagement and get stronger in our own right.

Does the US get defence ‘value’ from its relationship with Australia? Yes, absolutely. Washington looks to us to be a lead actor in stabilising our nearer region, the Pacific island countries and Timor-Leste. Washington wants Australia to be a strong shaper of security in Southeast Asia. In both cases, this means pushing back against growing Chinese influence in the region.

The US gets good intelligence value from Australia not just because we host a critical joint facility at Pine Gap, but because we offer serious intelligence know-how and insight about the Asia–Pacific.

Militarily, we are a valued alliance partner because we’re prepared to get into the fight and don’t just deploy forces for symbolic value. Yes, the Australian Defence Force is small, but from special forces to submarines and combat aircraft we bring some superb capabilities to the field, uninformed media criticisms notwithstanding. Don’t underestimate the access and influence that that effort delivers in Washington.

Finally, the US values Australia because of our geography. America needs ‘places not bases’ for its military so it can disperse more widely in the region and avoid being locked into a handful of large vulnerable bases in North Asia.

This means Australia can make a powerful case in Washington that we are a valuable partner, one that should be listened to and one that is intent on getting stronger more quickly, because of the growing Chinese threat to Asia–Pacific security.

The best way to insure against American isolationism is for us to be a stronger ally and, moreover, to do this in coalition with Japan, which has an equal imperative to keep the US engaged in Asia.

It’s likely that AUSMIN—the annual gathering of Australia’s foreign and defence ministers with their US counterparts—will happen in Washington later this month.

ANZUS was created in 1951 as the result of quick Australian policy thinking at a time of great strategic change in Asia. This is precisely what we need today. Typically, Australia drives the agenda for alliance cooperation. Frankly, we think about the alliance more than the US and have a sharp eye for how to maximise our return on investment.

Here we have an opportunity to repurpose the alliance. My advice to Defence Minister Peter Dutton and Foreign Minister Marise Payne would be to ditch their AUSMIN briefing packs, accept that the Asia–Pacific is heading into a five-alarm fire, and go to the States pitching for a fundamental alliance step-up.

First, let’s lift that US Marine Corps presence of 2,500 in the north to a full 7,500-personnel Marine Air–Ground Task Force. That task force comes with a lot of ships and aircraft, and the only place to house them in the short term is the Port of Darwin. It’s time to say goodbye to the lease that handed the port to a Chinese company for 99 years.

Second, we should ask the US to speed up its plans to bring more of its air force and navy presence into northern Australia. We need to urgently refurbish our remote so-called bare bases, which are falling into disuse. We should pay for this ourselves instead of hoping the US will take care of it.

That larger US presence in Australia would complicate any adversary’s plan to coerce us. We can shape that presence into a joint force, with equal sovereign weight for both countries. Nothing could be more reassuring to our neighbours, who worry equally about US disengagement and Chinese dominance.

This could all start happening next year. Contrast that with a plan for future submarines arriving in the mid-2030s.

Third, we need a decisive step forward in plans for joint missile design, manufacture and stockpiling in Australia. This will only be delivered if our political leaders decide they want to build this joint capability fast; otherwise, Congress could kill the idea.

Beyond missiles there are opportunities to promote joint projects in hypersonic weapons, quantum computing and autonomous land, sea and air vehicles. Both countries need to modernise their military forces, making them more relevant to the Asia–Pacific threat picture.

This is the threshold test. President Joe Biden can back his alliance rhetoric or succumb to ‘America first’ ideologies that just deliver America alone. Australia is positioned to make the case that the US needs its allies as much as the allies need America.

What is required here is a sense of speed, size and scale. If we default to standard defence planning nothing will happen for a decade, by which time the battle for strategic dominance in Asia will have been lost.

Dutton and Payne will arrive in a deeply demoralised Washington DC. Biden’s handling of Afghanistan has been disastrous, but what matters now is how America rebounds from this defeat.

Australia needs to bring its own design for the future of ANZUS to Washington, backed by a willingness to invest in our own idea and a rejection of rent-seeking. This will inject momentum and purpose into US security policy after Afghanistan and advance our national interests.

The United States rightly considers itself a ‘Pacific nation’. It has been engaged there almost since its founding—and the US west coast stretches to Guam.

Today, the US is indispensable to the region’s security. Remove it and see what happens. No single nation or combination of nations can withstand domination by the People’s Republic of China. The American presence also keeps certain other nations from going for each other’s throats.

But the US is dangerously overstretched militarily and, in locations such as the South China Sea, it’s overmatched.

Some sobering data: the People’s Liberation Army Navy has about 350 ships, though it’s 700-plus if you include China’s coast guard and maritime militia, which PLA planners undoubtedly do. The US Navy has just under 300 ships to cover the entire globe. And the PRC is launching four ships for each the US Navy builds. Play this out over a decade (or less) and, unless something changes, the PLA will be operating in force well beyond the so-called first island chain.

The US needs more ships and aircraft, operating from more places, and more missiles to counter the PLA’s massive rocket force. But even then, America wouldn’t be able to handle China by itself.

It’s not enough to beef up numbers. The US needs real partners that can operate with its forces and are willing to fight if necessary. That requires choices that regional nations deeply linked to PRC markets and scared of Beijing have been loathe to make.

The US can make the choice easier. It’s a major economic player but seldom uses this power to pressure adversaries, or to support friends. It had better start doing both.

Similarly, the US has scant physical commercial presence in much of the region, particularly in Central and South Pacific nations. These aren’t huge markets but, from a strategist’s perspective, they occupy key terrain. If you’re not there, you’re not interested, and the locals know it.

America’s political warfare (politely called ‘strategic communications’) is abysmal. Its diplomatic presence is limited—or non-existent—in too many places that matter. And, even when US diplomacy is present, political warfare seems not to be part of anyone’s job description. Beijing is running circles around Washington.

So, while the US has a base to work from, if it’s serious about remaining a Pacific nation, much less a Pacific power, it needs to get its military in order with appropriate funding, size, capabilities and locations; marshal and deploy its economic and commercial power; relearn political warfare; and sell itself and its influence (demand for US ‘green cards’ suggests this shouldn’t be hard). And it needs to do of all this with real partners. Australia, are you ready?

To politically and economically reinforce each other and the region, the US and Australia, in parallel or in tandem, should:

Such shortsightedness makes detoxing the US economy harder than it should be. I suspect things are only a degree different in Australia. If business and financial types can’t figure out which country’s name is on their passports or recognise that forced organ removals and concentration camps are bad, perhaps regulatory encouragement is required.

To thwart Beijing’s plans, the US and Australia could:

Now some military initiatives. It’s no coincidence that these come second. Without the political and economic efforts, military progress won’t make much difference.

The US and Australia could establish a joint multinational amphibious task force in the Northern Territory, perhaps in Darwin. It needs to be standing and not ad hoc or temporary. Consider the difference between getting together for a party and living together; they’re two very different relationships. Bilateral and multilateral exercises are good parties, but a permanent taskforce allows partners to really coalesce.

They should also pay special attention to Japan and the Japan Self-Defense Forces. Without a capable JSDF (which it currently is not) solidly linked to partners, our prospects are dim. Australia should assign an air force squadron to Japan, perhaps to Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni. The Japanese navy and army should be brought into the amphibious taskforce.

For the PRC, the political and economic realm and the military realm are fused with grey-zone activities, military and paramilitary. Then there’s the full range of economic, political, diplomatic and psychological activities that push one country’s interests at the expense of an adversary or enemy.

The PRC’s pulling nations away from Taiwan, planning a fishing port in southern Papua New Guinea and encouraging ‘independence’ movements in New Caledonia are all grey-zone operations. They’re as calculated as the PLA Air Force’s practice-bombing runs against Taiwan.

China has considerable success in the grey zone because there’s little to challenge it. Too often our response is to stare, semi-hypnotised, as at a cobra. That’s Beijing’s goal.

To break the spell, you must ignore the legal sophistry that claims China’s fishing fleet (and any Chinese company) isn’t part of the Chinese state, or that the maritime militia is a figment of the imagination.

Make it clear that you’ll push back, that you have the means to do so and, ideally, that you have friends who have your back. Have American and Australian (and Japanese) fighters accompany Taiwan Air Force jets to intercept PLAAF aircraft flying around Taiwan. This requires a willingness to take risks rather than just fret that Beijing might get angry.

As China gets stronger, the risks will get bigger. The sooner we push back, the better our odds.

Also, grey-zone assaults should not necessarily be matched act for act. If 500 Chinese fishing boats show up in the Torres Strait, don’t send 500 Australian boats (if they exist) to joust with them. Your counter will be more effective if it applies pressure where it will be felt.

You might suspend the Bank of China from the US dollar system, cancel residence permits and put liens on bank accounts of relatives of Chinese leaders—and expose and trumpet to high heaven those complicit in Chinese Communist Party corruption.

And don’t just be reactive. The US and Australia should conduct grey-zone activities together.

Addressing representatives from Central Pacific nations, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken criticised the PRC’s coercive lending practices—but he didn’t offer an alternative. That tells you plenty about where we are when it comes to addressing Chinese grey-zone actions, and the political warfare of which they are a part.

So, what are the odds of America maintaining its Indo-Pacific role 10 years from now? Maybe 50–50—and I never thought I’d say that in my lifetime. However, if Washington girds its loins and collects its wits and works with Canberra, Tokyo and New Delhi as real partners, the odds improve considerably.

But this will be, to borrow the Duke of Wellington’s reflection after Waterloo, ‘the nearest run thing you ever saw in your life’.

ASPI celebrates its 20th anniversary this year. This series looks at ASPI’s work since its creation in August 2001.

When ASPI was launched, intense argument raged between Australia’s regionalists and globalists.

Old arguments took on new life as government wrestled with the balance between defence-of-Australia and contributing to the global balance.

In the first decade of the 21st century, the globalists were on the up, as Australia joined the US ‘war on terror’ and expeditionary history was reworked in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In the second decade, the vision of the region grew to become the Indo-Pacific. Great-power competition returned and the Indo-Pacific was where the global balance would be set.

Over two decades, the globalist/regionalist difference both morphed and, increasingly, merged.

Power shifts remade strategic settings and stoked security fears.

Leadership changes in Australia saw three defence white papers in less than seven years: in May 2009, May 2013 and February 2016. This was a policy churn at notably shorter intervals than previous eras.

Australia’s government was worrying more about strategy—but not necessarily doing a better job dealing with the changes under way.

ASPI’s Andrew Davies commented that the 2009 and 2013 white papers failed to be as influential as might have been expected, writing that ‘DWP 2009 promised big and delivered little, while DWP 2013 was more an exercise in treading water for political purposes than a serious attempt at matching defence resources to the strategic challenges of the day.’

Reviewing the history of defence white papers since the first in 1976, historian Peter Edwards saw the ‘short and unfortunate shelf-lives’ of the 2009 and 2013 white papers as victims of a challenging international environment and domestic political turbulence:

It’s little wonder that analysts this century have found it hard to make confident assessments of the next generation’s strategic threats. Moreover, Defence White Papers have been caught up in the severe political tensions between and within the major political parties. The rapid turnover of defence ministers and more recently prime ministers has further impeded long-term planning. Defence budgets have been raided for electorally popular policies.

The transformation of major-power relations was having a ‘profound effect’ on Australia, strategists Paul Dibb and Richard Brabin-Smith wrote in 2017 ‘Australia’s strategic outlook is deteriorating and, for the first time since World War II, we face an increased prospect of threat from a major power. This means that a major change in Australia’s approach to the management of strategic risk is needed.’

ASPI’s Malcolm Davis judged that an assertive China directly challenging US primacy in Asia meant Australia was now a state in the front line, geographically, strategically and politically: ‘The geographical barriers and the ‘tyranny of distance’ are being eroded with the onset of technological innovation in new military domains, such as space, cyberspace and across the electromagnetic spectrum … A mindset of assuming we can defend the sea–air gap is becoming less and less credible.’

The Australian Defence Force must play a greater role throughout maritime Southeast Asia and the South Pacific, Davis advocated, to ‘extend our defence in depth far forward’.

On the traditional strategic agenda, pandemics and other health emergencies are generally listed in the same category as climate change and bushfires—posing security threats rather than changing strategic orders. The reason, as ASPI senior fellow Rod Lyon observed, is because strategy and war are about politically motivated violence, not sickness and death. Then came Covid-19.

The geopolitical impact of the pandemic, Lyon said, was to accelerate the existing trends of a strategically competitive world:

If Covid-19 is accelerating those changes—magnifying their intensity and compressing the time taken for them to work through the system—we will emerge from this pandemic to a sharper, more competitive world, where our main ally is less influential and where multilateral institutions are increasingly under the sway of other great powers that believe in hierarchy, and not in equality.

In the 2020 strategic update, the government pronounced that Australia’s strategic environment had deteriorated, with these words from Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Defence Minister Linda Reynolds:

Our region is in the midst of the most consequential strategic realignment since the Second World War, and trends including military modernisation, technological disruption and the risk of state-on-state conflict are further complicating our nation’s strategic circumstances. The Indo-Pacific is at the centre of greater strategic competition, making the region more contested and apprehensive. These trends are continuing and will potentially sharpen as a result of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.

The update ditched 50 years of strategic theology: Australia no longer believed it has 10 years’ warning time of a conventional conflict, based on the time it’d take an adversary to prepare and mobilise for war: ‘This is no longer an appropriate basis for defence planning. Coercion, competition and grey-zone activities directly or indirectly targeting Australian interests are occurring now.’

Launching the update, Morrison several times compared the deterioration in Indo-Pacific security to the slide to global war in the 1930s: ‘That period of the 1930s has been something I have been revisiting on a very regular basis, and when you connect both the economic challenges and the global uncertainty, it can be very haunting.’

Pointing to those words, ASPI boss Peter Jennings commented:

The biggest change in the strategic update is temporal, not geographic. The Indo-Pacific—now defined for defence planning purposes as the northeastern Indian Ocean, Southeast Asia, Timor-Leste and the Pacific islands—has been at the core of Australian strategic thinking for decades. What is new is the realisation that the risk of conflict is upon us right now, not a comfortably distant 20 years away.

Journalist Geoffrey Barker called the update ‘a pivotal moment in modern Australian military history’, marking an ‘unambiguous return’ to the defence-of-Australia policy: ‘Of course, the new policy has evolved from earlier defence white papers and updates. But it just as clearly represents a new (or rediscovered) way of looking at the strategic order and finding policy and acquisition solutions that offer new ways of addressing China’s authoritarian arrogance.’

The expanded geography of the Indo-Pacific acknowledges that key elements of the central balance have arrived much closer to Australia.

The main game has come to us, as the tectonic ripples of power lap at the concentric circles of Australian strategy.

At the start of ASPI’s life, the 9/11 attacks changed the shape of the post–Cold War world. Two decades later, Covid-19 accelerated the new era of strategic contest in the Indo-Pacific.

A clear strategy of the Biden administration is to repair relations with allies and partners and to build up the cooperation with them before negotiating with China, says Australia’s ambassador to the United States, Arthur Sinodinos.

In a video address to an ASPI masterclass on ‘The US–Australia alliance in a more contested Asia’, Sinodinos said there were areas where the US wanted to compete with China, particularly around technology, and others where it wanted to cooperate with China—climate change being a major one, along with nuclear non-proliferation and the aftermath of Covid-19.

‘Their attitude is there are areas where we will compete, areas where we will cooperate, and there may be areas like human rights where basically we just have to confront and call it out and no linkage between the two,’ Sinodinos said.

‘They built up to the phone call between the president and President Xi, and then of course, the meeting in Anchorage between senior foreign and security officials of US and China. So, it was all done in sequence.’

The message to China at Anchorage was that the US was working with its allies and partners and there could be no reset of the relationship between the US and China unless China also reset its relationship with allies and partners, including Australia.

‘John Kerry, the Special Presidential Envoy for Climate Change, has made it clear, no deal on climate change between the US and China at the expense of the US’s other interests.’

Having served in varied roles, Sinodinos is one of Australia’s most experienced diplomatic and political figures. He was chief of staff to Prime Minister John Howard for 10 years, was a minister in the Abbott and Turnbull governments and has been ambassador to the United States since early 2020.

Sinodinos said that under the Biden administration the US–Australia alliance was going from strength to strength. ‘I think that reflects a conscious decision of this administration to place more emphasis on the role of allies and partners,’ he said.

‘They’ve looked at the world as it’s become, they’re not trying to hark back to the Obama era, they’re not seeking to airbrush the Trump era. I think what they’ve done is reflect on the lessons of the last few years in global politics and geopolitics and they’ve come to the conclusion that with the rise of China and with the way in which China seeks to assert its growing power, that allies and partners are a significant force multiplier from an American perspective.’

The Biden team had concluded that America needed to reassert its presence, particularly in the Indo-Pacific, and use that as a basis for working with allies and partners to push back in areas of overreach and to encourage China to think about how it adapted to the rules-based order rather than to create its own order.

‘From our point of view, this is a very important exercise,’ Sinodinos said.

‘The China of today is very different from a few years ago. It’s now more conscious of its power,’ he said. China was now exercising that power in ways people didn’t expect a few years ago. Sinodinos said he was one of those who thought China would grow up to be a version of Singapore or Taiwan on steroids, but that was not how it had developed.

‘That means that we have to adjust how we think about China. We have to adjust how we work with allies and partners.’

He said the goal should not be to contain or suppress China but to promote a strong and prosperous China which would be a productive member of the rules-based order in which the norms and institutions created, as much as possible, a level playing field among countries great and small.

In that context, the US–Australia alliance had never been more important and the US realised it was a significant advantage in dealing with China.

In the first few months of the Biden administration, a lot of work had gone into repairing relations with allies and partners. ‘That was not so much a challenge in the case of Australia, but there’s been work with partners in Europe. There’s also been work with Korea and Japan, particularly in seeking to deal with some of the issues that they have between themselves, so as to create a more harmonious set of allies and partners who can work together.’

Sinodinos said that before Kurt Campbell became Biden’s Asia coordinator, Australia’s representatives in the US had a number of seminars with him and his team about Indo-Pacific policy, including about what might happen with the Quad, how the US should approach ASEAN, and how they could work together to push back on economic coercion by countries like China.

Sinodinos said it was gratifying to the Australians that a US priority was an early meeting of Quad leaders. It was important that Biden and his team did not reject the idea of the Quad because it had been advanced under Donald Trump. ‘They looked at issues like the Quad on their merits and decided this is good, we should build on this.’

The Quad agenda now had three parts: vaccine diplomacy, climate change, and critical and emerging technologies, Sinodinos said. There was a critical need to ensure maximum vaccine production and delivery in this region as a template for what it might roll out in Africa and Latin America. That would involve a permanent step-up in capacity for production and delivery, recognising that this pandemic was not over and the world had to prepare for future pandemics.

The Quad nations would work together on climate change, on developing low-emissions technologies and other critical and emerging technologies sitting at the intersection of economics and national security, such as artificial intelligence, quantum computing, hypersonics, cyber and space.

There was a recognition that a challenge in the post-pandemic era, and as a consequence of technological competition with China, was to reconfigure supply chains around trusted partners. ‘And that of course has a security dimension to it,’ Sinodinos said. ‘It also has an economic dimension. It will create opportunities for Australia.’

For Australia, the Quad was more significant than ever, but it complemented the other architecture in the region, including the central role of ASEAN and APEC in the economic and trade space.

‘It’s not meant to supplant them. It’s not meant to be an Asian version of NATO. It’s not meant to be institutionalised or bureaucratised with its own secretariat.’

Sinodinos said the defence and security aspects of the US–Australia alliance were strong and would be built on further.

‘We also want to make the economic and trade aspects of our relationship with the US even stronger. We’re looking to have a strategic economic dialogue with the US which encompasses the sort of critical and emerging technologies and other matters … where national security increasingly impinges on the economic space. For us that dialogue will be an important complement to our other activities. We want that pillar to be as strong as the AUSMIN pillar in the relationship.’

Sinodinos said Prime Minister Scott Morrison had made it clear that in seeking to further deepen engagement with the US and in encouraging the US to play a greater role in our region, Australia was not seeking to have it carry an undue share of the burden of the alliance.

‘The defence strategic update made it clear, we want to carry our share of the burden, and the Americans recognise that. We got top marks for that when it was announced last year both from the then administration and from the Congress. And today, this administration recognises we’re prepared to do heavy lifting on our own behalf and as part of the alliance.’

Sinodinos said this would create opportunities, not only in a defence and security sense, but also in an economic sense. ‘I’m very optimistic about where the alliance is going. There’s a lot of clarity around objectives.’

Returning to the Quad, Sinodinos said it was underpinned by a vision that democratic governance had not run out of steam and that the West and the US were not in relative decline. ‘We have confidence in our institutions and our values, and we are prepared to stand up for those in our region.’

While some peddled a narrative that the US wasn’t interested in the region or that it was in relative decline, said Sinodinos, ‘I think the opposite is the case. The lesson from the history of the US is whenever they seem to have gone into decline, they’ve bounced back. There’s enormous resilience in the system.

‘And on the economic side here in the US I can tell you, over the next few months as the economy continues to recover from Covid, we’re going to see a very strong recovery which will also have a major impact on the recovery in Australia.’

From a military point of view, Australia’s drive to produce more of its own munitions would be done in conjunction with the US, along with research on ‘frontier technologies’.

Sinodinos said Australia must, from a strategic perspective, keep encouraging the US back into the region in the trade and economic space to help set rules and standards.

Getting the US into the Trans-Pacific Partnership to make it the region’s biggest trade agreement would be important. At present, the TPP was, Sinodinos said, ‘a bit like Hamlet without the prince’.

Having the US in the TPP would maximise its benefits and enable it and like-minded countries such as Australia to set the rules and standards in the region.

‘In the meantime, we’re engaging the US on a digital trade agreement, which may be either bilateral or regional. It’s based on the sort of agreements, for example, that we have with Singapore, high-quality digital agreements, which promote digital trade.’ That would, in particular, ease the burdens of small businesses involved in areas like e-commerce through the recognition of payment systems across borders. ‘All of this is the bread and butter of trade, but it’s important as a way of engaging the US further in the region.’

Sinodinos said he dined last week with the senior leadership of the US House Foreign Affairs Committee and its Asia Subcommittee in the Congress. He found a surprising level of support for the TPP. ‘So, I’m quite optimistic that we can put together a coalition of the willing on this sort of stuff.’