Outcry for Assange oddly absent for those held by China

As the Julian Assange extradition case proceeds through Britain’s justice system, the publicity of his supporters is constant and loud with its demand the Australian government intervene in another democratic country’s legal process. The hypocrisy is even louder.

Allegra Spender, shortly after becoming the new member for Wentworth, took to Twitter to demand Prime Minister Anthony Albanese call US President Joe Biden to ‘urge him to intervene so Julian Assange isn’t unjustifiably imprisoned’. Spender joins the calls from the Bring Julian Assange Home Parliamentary Group, chaired by Andrew Wilkie, and former parliamentarians including George Christensen, Bob Carr and Craig Kelly, who are demanding the US drop the case and, in some instances, implying or stating the US legal proceeding is politically motivated.

Supporting Assange is everyone’s right, but the freedom to criticise the US, and in this case make demands of Britain, is not a freedom that is applied equally around the world—not by the business community, our universities or parliament. There are those such as Carr who argue that Chelsea Manning, the former US Army private who admitted to passing classified information to WikiLeaks, is no longer in jail so Assange shouldn’t be either. These comparisons are a stretch given Manning went through a trial at which she was found guilty and later had her sentence commuted. Assange and his supporters do not only claim innocence but also that the justice system should not be allowed to test that. Assange is therefore above the law.

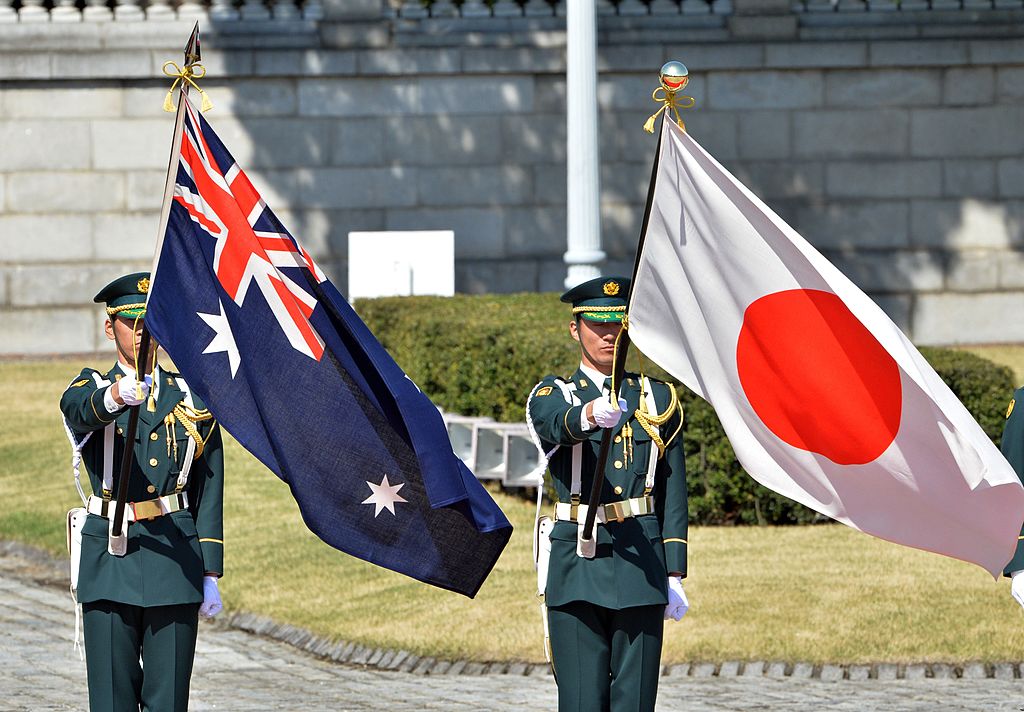

Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Richard Marles has said, correctly, it ‘is a matter for the United Kingdom’. But calls to intervene in other countries’ democratic judicial systems show the extent of the hypocrisy when we deal with our biggest trading partner.

Where is the loud constant cross-party effort in relation to Australians detained in China? Where are the business leaders demanding Yang Hengjun and Cheng Lei be released? Both Australians, Cheng is a journalist unable to see her children while Yang is a writer suffering numerous health issues. How often do you hear Assange supporters talk about them or those Australians on death row in China, one of whom, Ibrahim Jalloh, is intellectually disabled?

It boils down to this: global fear of being punished by China for any criticism versus the confidence that the US and the UK will rationally engage. Punishment could include more economic coercion against Australia or a death sentence being carried out. So much for freedom and sovereignty when it is available only with those countries that aren’t constantly threatening us.

The hypocrisy is matched by many Muslim-majority countries that have the freedom to criticise Israel in relation to its treatment of Palestinians but are too scared or don’t care about Muslim minorities in China.

Forty-seven countries recently signed a UN Human Rights Council statement expressing concern about human rights abuses in Xinjiang. Albania was the only member of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation to join. The rest chose silence or joined China’s counterstatement that Xinjiang should be off limits to international discussion.

What’s the difference between Muslims in the Middle East and the Indo-Pacific? Money and power.

Similarly, we see the different treatment of the US and the authoritarian regimes of Russia and China through international responses to the invasion of Ukraine. In 2003 Megawati Sukarnoputri, the Indonesian president at the time, called the US invasion of Iraq ‘an act of aggression, which is in contravention of international law’ and ‘threatened the world order’. Although joining the UN General Assembly resolution condemning Russia, Indonesia has not done so separately, instead looking at ‘the aspirations of all parties in a balanced manner’.

In arguing why they won’t speak against the Russian invasion, many in the Indo-Pacific argue they are neutral or non-aligned and the US shouldn’t expect support given the Iraq war.

But herein lies the hypocrisy—they can criticise the US-led war in Iraq freely but are unable to condemn Russia. True neutrality would be a consistent approach. This inconsistency serves only to boost the confidence of authoritarian states such as Russia and China to carry on with their malicious and egregious activities.

The hypocrisy is also shown by those who rightly call out Saudi Arabia, whether it be the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi or the criticism of golfers playing in the new Saudi Arabia–backed professional golf league, but fail to apply those same standards to Beijing. Many companies and brands continue to operate in Xinjiang, with some still partnering with factories across China that are using forced Uyghur labour. Outside of the Women’s Tennis Association in relation to Peng Shuai, how many global sports organisations or indeed individual sports stars put human rights above Beijing’s money?

The freedoms we enjoy in Australia, including to express ourselves and to assemble and protest, are at the heart of our national sovereignty and that of other liberal democracies. Discretion and balance in how we use such freedoms are important, but we risk constraining sovereignty and promoting self-censorship if we and our partners speak out only against those who cannot or will not hurt us.

There is, of course, the valid principle that we should hold the US and other democracies to a higher standard than that we expect of authoritarian regimes. This is true, but we should hold ourselves as nations and individuals to that same high standard. This means parliamentarians, businesses and academia putting human rights ahead of economic gain. It also means being frank with countries with which we claim to be friends that true neutrality is not criticising democratic partners while remaining silent on China or Russia.

The ability to speak up for Assange, with all his renowned wealth and contacts, is a sign of Australian freedom. Our inability to speak up for Yang, Cheng and all those who have no such luxuries is a sign that our freedom is limited by money. We should demand that the individual rights of all are worth speaking up for no matter the country involved.