Indo-Pacific versus Asia–Pacific as Makinder faces Mahan

When Australia adopted the term ‘Indo-Pacific’ five years ago—replacing ‘Asia–Pacific’—the aim was to widen Canberra’s understanding of ‘the region’. ‘Ho hum’, said the region. Now, the idea of the Indo-Pacific is humming.

Japan’s Shinzō Abe likes the Indo-Pacific because it fits his ambitions for a greater Japanese role in Asia. Abe thinks big and Indo-Pacific is a big label that reaches beyond the bilateralism of the US alliance.

India embraces the Indo-Pacific because it honours India’s vital role in Asia’s future.

Indonesia cautiously puts its hand on the Indo-Pacific, not least because Indonesia sits in the middle.

ASEAN pokes at and frets at a fashionable usage that’s spreading quickly, worried what it might mean for ASEAN ‘centrality’. Southeast Asia might be in the centre of the geography but ASEAN feels outside the idea.

All this leads to the nation that has turbocharged the Indo-Pacific discussion—the United States.

The Trump administration adopted the Indo-Pacific with such gusto, it starts to smell like a strategy. Fascinating says the region, ‘What can it mean?’

In a matter of months, Indo-Pacific has become the defining way that Washington describes the region. Donald Trump likes a new label that doesn’t belong to Obama; in Trumpworld, that’s all the reason you need.

The Trump national security strategy and companion national defence strategy use ‘Indo-Pacific’, with zero sightings of the Asia–Pacific. ‘Mesmerising’, says the region.

China’s response to the Indo-Pacific trend is both complex and simple.

The simple bit is that Beijing hates the idea. The complex side is that while it smells and sounds like a US strategy, Indo-Pacific is so new in Washington’s lexicon that policy content is slight—a major idea with little mass bothers the hell out of Beijing.

For now, China can sit with its simple response: hate it. And worry how this new bit of Trump kit is going to work.

Compare Indo-Pacific with Asia–Pacific to see different hierarchies as well as geographies.

China likes Asia–Pacific because it references the land mass that China thinks it naturally dominates, plus the ocean that stretches to the US. Asia–Pacific translation: Asia = China while Pacific = US.

The Indo-Pacific is a maritime concept while the Asia–Pacific tries to link the maritime with the continental.

Indo-Pacific skips by the Asian land mass (China) and replaces it with two oceans.

The translation into nations can read Indo = India while Pacific = US. Such a reading spurs Chinese paranoia about being contained and constrained between two oceans, facing the US on one side and India on the other. And when it comes to modern confrontations with India, China’s experience is on land, not sea.

Give this a theoretical tinge with two old, opposing views of geography and strategy: John Mackinder versus Alfred Mahan.

The land element of the Asia–Pacific and a Chinese reading of it leans towards Makinder’s 1904 theory about the Eurasian landmass that dominates the world.

The two‑ocean expression of the Indo-Pacific would enthral the US naval officer Alfred Mahan, whose 1890 book on sea power shaping history still inspires the salts.

Mackinder would understand the import and ambition of China’s Belt and Road Initiative for the Eurasian heartland.

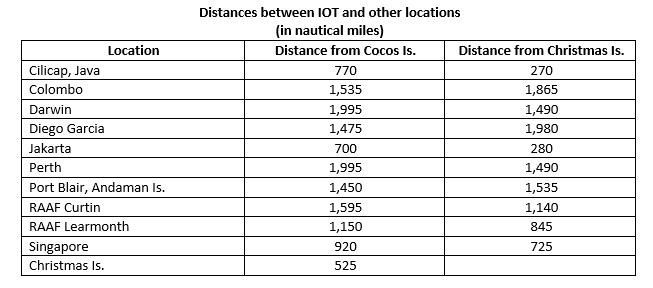

Mahan would salute the symbolism and intent of last week’s announcement from Pearl Harbor that the US Pacific Command is renamed the Indo-Pacific Command. Pacific Command’s remit has always run from Hollywood to Bollywood (Malibu to Mumbai)—now the name fits the range.

The US Defense Secretary, James Mattis, flew from the Hawaii naming ceremony to the Shangri-La dialogue in Singapore, where he used the term ‘Indo-Pacific’ 17 times in his speech, and ‘Asia–Pacific’ only once (referring to APEC).

To show the nomenclature shift, on the same stage last year, Mattis used ‘Asia–Pacific’ nine times and ‘Indo-Pacific’ only once (quoting India’s Narendra Modi). Back then, the commander of what’s now Indo-Pacific Command was hedging by referring to the Indo-Asia-Pacific.

As the keynote speaker at Shangri-La this year, Modi gave the geographic vision the full treatment: ‘The Indo-Pacific is a natural region.’

India’s prime minister offered ASEAN love and China reassurance:

India does not see the Indo-Pacific region as a strategy or as a club of limited members. Nor as a grouping that seeks to dominate. And by no means do we consider it as directed against any country. A geographical definition, as such, cannot be.

Modi offered these Indo-Pacific elements:

- A free, open, inclusive region.

- ‘Southeast Asia at its centre. And, ASEAN has been and will be central to its future.’

- A rules-based order for the region applying ‘to all individually, as well as to the global commons’. The order is based on sovereignty, territorial integrity and ‘equality of all nations, irrespective of size and strength. These rules and norms should be based on the consent of all, not on the power of the few.’

- Equal access as a right under international law to the use of common spaces.

- Not protectionism but globalisation: a ‘rules-based, open, balanced and stable trade environment in the Indo-Pacific’.

- Connectivity is vital: ‘We must not only build infrastructure, we must also build bridges of trust … They must promote trade, not strategic competition.’

- The India–Indonesia comprehensive strategic partnership announced last week is based on ‘a common vision for maritime cooperation in the Indo-Pacific’.

Modi began his final words with a hope that’s also a caveat: ‘All of this is possible, if we do not return to the age of great-power rivalries.’

On that hope, Makinder and Mahan would share doubts, whatever the geographic frame.