Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

The Royal Australian Navy is strongly focused on building relationships with allies and gaining experience in an increasingly complex and uncertain Indo-Pacific region, says its commander, Vice Admiral Michael Noonan.

‘The geopolitical climate that we find ourselves in is unpredictable’, the navy chief told The Strategist. ‘It’s probably more dynamic than we’ve seen the Indo-Pacific, and it’s changing quite rapidly.’

Noonan says this highlights the importance to Australia of shipping and lines of communication. ‘They are probably more important now than we’ve realised in the past and it’s clear to me that the maritime domain is front and centre in the thinking of our political and strategic leaders as we look at security and prosperity for Australia and the region in the years ahead.

‘The growing competition we are seeing in the region is testament to that. So, I feel very deeply about the responsibility that our navy has in terms of working ultimately with the other elements of national power.’

The navy chief has engaged closely with the secretaries of relevant departments on what must be achieved in the maritime domain and in maritime security. ‘I don’t profess to have all the answers, but I think we’ve a very clear direction that we’re committed to.’

A key goal in his official statement of intent as navy chief is to ensure that the RAN is ready to conduct sustained combat operations as part of a joint force—both with other parts of the Australian Defence Force and with regional partners—by 2022 and to maintain a long-term presence away from its home ports.

Asked if the navy could carry out such operations indefinitely, Noonan says that at this stage it clearly could not. ‘But we need to understand how long we might need to stay out there. It’s about being prepared, and, in some cases, being prepared for the unexpected, and being prepared to do those things that we might not necessarily have done in the past.’

That’s a big step from where it’s been operating over the past 20 years with finite deployments such as the sending of a single frigate to the Middle East for six months as part of a coalition.

With three years left to serve as chief, Noonan wants to ensure that the service can maintain the pace it’s now operating at, while evolving into a fifth-generation navy. ‘It’s not about being able to do everything ourselves. There are very capable platforms and systems we can operate by ourselves, but we’ve got to ensure we can operate with our partners and allies in the region.’

The navy spends a lot of time in the region and Noonan travels often to talk to his counterparts.

‘Certainly, that’s evidenced by the breadth and number of people that we’ll have at the Sea Power Conference and Pacific 2019’, he says. The attendees include about 45 delegations and 21 chiefs of other navies.

At the conference today, Noonan launched the navy’s industry engagement strategy, which seeks to bring what has been largely a transactional relationship with industry to a more persistent partnership. ‘I believe that industry and academia have got a lot to offer in helping our navy find a better way to achieve what we must in the future. They’ve a lot of experience, a lot of learning regarding how we can do better with our people, how we improve our processes, how we harness emerging technologies and use them to their full capacity.

‘We’ve got to make those people in industry and academia feel that they’re part of the navy, enabling us to do what we have to do when we deploy.

‘Part of that, for me as a capability manager, is ensuring that I’m engaging those folk so that they understand what we’re doing, why we’re doing it, where we’re doing it, when we’re doing it, so that they can focus their efforts to the best of their ability.’

Noonan says he’s getting a sense that people from industry see that the navy wants to be closer to them. ‘I’ve talked a lot about being trusted partners. I’ve talked a lot about transformational relationships, and ultimately, it’s about having a shared awareness of what the role of the navy is and how we might best introduce it into the future.’

As an indication of the rapidly growing importance of regional relationships, Noonan will fly to Japan when the conference finishes. There he’ll join four RAN vessels led by the new air warfare destroyer, HMAS Hobart.

The RAN contingent of three surface ships and a submarine will take part in the Japanese fleet review in mid-October. ‘That underlines the importance of Japan and the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force as a close and strong partner with the RAN’, Noonan says.

‘I personally look at the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force as being our most important and capable regional partner in the way that we operate with them. Clearly, we’ve got a very special and strategic relationship with Japan. We have shared democratic values, shared interests. And we have a very, perhaps, strong and close alliance with the US in that relationship as well.’

Noonan says the alliance with the US is clearly Australia’s most important defence relationship, but others in the region are very important also.

And the value of the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing relationship with the US, Britain, Canada and New Zealand should never be understated. ‘My personal relationship and commitment to my Five Eyes counterparts is absolute. I communicate with them regularly. I see them regularly. We share information. We share thinking, and we share opportunity to grow as navies through that commitment to our shared ambitions on maritime security.’

Relations with other neighbours such as Singapore and Indonesia are very close.

Further afield, the relationship with France and Spain is deepening. ‘That’s not just because we’re building submarines and ships with these countries but because we are doing more together in the Pacific.’

In preparing for future operations the navy is drawing on the many lessons it has learned about seaworthiness and airworthiness, Noonan says.

‘Ultimately, we’ll learn from those two domains as we move into other domains such as cyber. I’m applying the term “cyber worthiness” to the fleet to ensure that our ships, our aircraft and our systems can operate in a sustained manner in a cyber environment.’

Noonan has set 2035 as a line in the sand where Australia will have a mature understanding of what the future navy will be. ‘We’ll be in the middle of transition to the new frigates. We’ll have all the new OPVs [offshore patrol vessels] in service. We will have transitioned to the Attack-class submarine. Certainly, we expect to have the first submarine in navy service, and the second Attack-class submarine will be built.

‘For me, it’s an epoch in time, where we will see that move from our current fleet to the future fleet.’

After more than a year of deliberation, ASEAN adopted the ‘ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific’ on 23 June. The outlook then got an airing at the ASEAN Regional Forum meetings in Bangkok. The document ‘provides a guide for ASEAN’s engagement in the Asia–Pacific and Indian Ocean regions’ and resembles an Indonesian-conceived plan.

The idea of the Indo-Pacific as a regional concept isn’t new and has been widely discussed in the policy community as a way to link the Indian and Pacific oceans, and give greater recognition to the role of India and Indonesia in any regional strategic formulation. But the Indo-Pacific concept took on more life and meaning with the Trump administration’s adoption of it.

As a leader of ASEAN, Indonesia is uncomfortable with the US approach, seeing it as an exclusionary and aimed at isolating China. Jakarta sees the ‘Quad’—comprising the United States, Japan, Australia and India—as a potential strategic coalition of ‘outside’ powers without ASEAN’s involvement. In response, Jakarta has been developing an ASEAN-centred Indo-Pacific strategy that is more consistent with ASEAN’s principles of inclusiveness (including towards China) and consensus-building, and its stress on a normative, political and diplomatic—rather than an excessively military–strategic—approach.

The differences are captured in the terminology used by the two countries to articulate their Indo-Pacific visions. Briefly, the US wants a ‘free’ and ‘open’ Indo-Pacific, echoing the wording used by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, but with a more overt military–strategic orientation. In comparison, Indonesia seeks an ‘open’ and ‘inclusive’ Indo-Pacific. The US doesn’t use ‘inclusive’, while Indonesia doesn’t use ‘free’.

The US idea of a ‘free’ Indo-Pacific identifies domestic political openness and good governance as key ingredients—putting it at odds with China—while Jakarta’s stress on ‘inclusivity’ implies that its policy is not meant to isolate China. India seems to be taking a middle path, calling for a ‘free, open and inclusive Indo-Pacific Region’.

The outlook upholds the vision put forth by Jakarta, whose interest in the Indo-Pacific idea is driven by President Joko Widodo’s goal of turning Indonesia into a ‘maritime fulcrum’. ‘The Outlook is intended to be inclusive in terms of ideas and proposals.’ There’s no mention of any country or major power, not just China and the US, but also Japan, India and Russia. It avoids any strategic language or tone and there are no military aspects to the document.

Rather, it is more consistent with ASEAN’s ‘comprehensive security’ approach with an emphasis on ‘implementing existing and exploring other ASEAN priority areas of cooperation, including maritime cooperation, connectivity, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and economic and other possible areas of cooperation’.

The outlook strongly recalls the traditional ‘ASEAN way’ of avoiding legalistic institutionalisation—it’s meant to be a ‘guide’, not a legal document or treaty.

Moreover, the outlook stresses reliance on existing ASEAN norms and mechanisms, such as the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia and the East Asia Summit. It’s ‘not aimed at creating new mechanisms or replacing existing ones; rather, it is an Outlook intended to enhance ASEAN’s Community building process and to strengthen and give new momentum for existing ASEAN-led mechanisms to better face challenges and seize opportunities arising from the current and future regional and global environments’. This reflects a determination to preserve ASEAN centrality in the development of Indo-Pacific architecture and counter any linking of the Indo-Pacific to a balance-of-power approach.

Some Western observers dismiss the outlook’s importance because it doesn’t target China specifically or carry compliance measures, but this criticism misses the point: this is how ASEAN has been doing its business since its founding. ASEAN’s main roles in regional security have been in norm-setting and confidence-building, rather than in exercising hard power or conflict-resolution.

What’s disappointing is not the document, but the gap between how the West sees ASEAN and how ASEAN sees itself. ASEAN is bound to disappoint those who would like to see it act like a great power in a classical concert of powers. That is not what ASEAN is or what it will ever be.

While the outlook is written in typical ‘ASEAN speak’, it doesn’t blank out the crucial issues and principles at stake in current maritime disputes in the South China Sea. The document stresses ‘cooperation for peaceful settlement of disputes; promoting maritime safety and security, and freedom of navigation and overflight; … sea piracy, robbery and armed robbery against ships at sea; and the like’.

The outlook avoids the term ‘free’, which China sees as being directed against it. At the same time, it contains references to ‘freedom of navigation’, which is Washington’s area of emphasis. ASEAN is playing its classic role as a regional consensus-builder, which is all the more essential at a time of rising bilateral tensions between the US and China.

In the final analysis, the outlook is an act of diplomatic and political assertion by ASEAN. ASEAN is telling the world that it has its own way of developing the Indo-Pacific idea—previously pushed by outside powers such as Japan, Australia, India and the US—and that it won’t let outside powers dominate the ‘discourse’ on the Indo-Pacific. The outlook also legitimises the role of Indonesia, possibly the only Southeast Asian country with the size, geography and potential power to stand up to China and the US, or indeed to all major powers. This is what’s critical to the preservation of ASEAN centrality.

‘We live in an era of increasing competition where the rules-based international order is coming under increasing pressure.’

— Lieutenant General Rick Burr, Chief of the Australian Army

This key observation in the army chief’s ‘futures statement’, Accelerated warfare, goes to the heart of the service’s fundamental purpose in the 21st century. Identifying the drivers of this intensifying competition is crucial to understanding how the army’s strategic environment will evolve, why the increasing pressure on the rules-based order is of such importance, and how that pressure reinforces the significance of Australian land forces in the Indo-Pacific.

Competition is driven by scarcity and, beyond a certain threshold, it can easily morph into conflict. (The idea that competition results from scarcity is an economic construct. Another theory, from the international relations literature, is that competition and/or aggression can arise from attempts to rectify a real or perceived historical grievance. Both explanations are justifiable, but for the purposes of this article I’ve used the scarcity model.)

Integral to the concept of scarcity is the need for a system of rationing that forms the rules of the game, which help decide who can lay claim to the thing that’s scarce. These rules can be deliberately produced and enforced or they may arise organically and manifest as cultural customs, national values, and so on.

Scarcity is a ubiquitous fact of modern societies, as are the rules used to address it. The rules can change over time, either by design or by default. Those who like the rules work hard to preserve them, including by creating the institutional structures to perpetuate the status quo. Those who don’t like the rules try to change them, through persuasion, enticement, coercion or outright aggression. The campaigns for civil rights and women’s rights, for example, have been instrumental in shifting the criteria for social advancement from skin colour and gender to merit.

On the other hand, trends like population growth, urbanisation and the spread of technology are changing not just the rules of the game, but also the fundamental scarcities themselves. Shortages of food, energy, resources, jobs and housing are affecting national policies and international relations. Advancements in communications and medicine are allowing people to work remotely and well past the typical retirement age of 65, which, incidentally, affects the advancement prospects of the younger cohort.

It is in this context that the increasing competition between major powers and the pressures on the rules-based order become significant. The Indo-Pacific region already accounts for over 60% of the world’s population and that number is expected to grow over the coming decades. How to provide adequate opportunities for increasing populations is the primary challenge for all countries. This is intensifying the already critical scarcities of access and authority, such as access to resources, markets and skills to ensure economic growth, and the authority to use military or economic force to assert national interests. These scarcities have prompted a global competition to secure resources and power—as much as possible, as fast as possible, by whatever means necessary.

For much of the post–World War II era, such scarcities have been resolved by the rules of accountability and multilateral cooperation. Those rules (and any intercountry disputes) were adjudicated through the various institutions of the Bretton Woods system, which was created and led by the United States. The principles underlying the system were national sovereignty, the rule of law, individual liberties, free markets and free trade.

Any military action against other countries was supposed to be approved by a community of nations, and (relatively) equitable access to resources and markets was facilitated by participation in the international economic system. These rules haven’t always been followed and many violations have come from countries, including the US itself, but overall the system has ensured peaceful coexistence for much of the past 70 years and helped pull millions of people out of extreme poverty.

However, in the early 21st century, that system is being challenged by both populist governments and violent non-state actors. At their core, challenges to the rules-based system are little more than efforts to change the criteria by which critical scarcities are resolved. Rather than legitimising their claims through accountability and cooperation, the challengers are trying to normalise totalitarian absolutism and unilateral aggression as the new rules.

The game is shifting from one of mutual prosperity and shared values to one in which competition is a zero-sum proposition and might is right. This might be happening because the existing rules are no longer perceived by those involved to provide fair, effective or fast enough access to the resources and power they seek. Whatever its causes, this is a dangerous trend. If left unchecked, it could drive the region into chaos and leave the smaller countries and vulnerable groups at the mercy of the larger, more powerful ones.

As the 2016 defence white paper notes, these efforts represent a core strategic threat for Australia and therefore need to be effectively countered. The most important question for Australia is whether it can play by these new rules. The answer should be an obvious, unequivocal, ‘no’. If this new order takes root, it could cripple the framework which has helped Australia become one of the most peaceful and prosperous societies in the world, and in which it naturally plays to its strengths.

So, how can the Australian Defence Force, and the army in particular, help defeat efforts to undermine the rules-based order, and what capabilities does it need to do so?

The ADF has a lot going for it. While it’s comparatively small in the region, the ADF draws its strength from values whose power is far more enduring than that of totalitarian systems. In a region beset by historical, identity-based conflicts, the ADF draws further strength from its evident neutrality, which confers on it credibility as a trusted partner and interlocutor.

But the impact is not uniform. While the defence of liberal democratic values has to be a joint force effort, the maximum, lasting impact can only come through the sort of direct contact that the army achieves. That’s what makes it real and personal. Through its demonstrated prowess and proper conduct towards civilians, the army can infuse values that can percolate into the public discourse and politics of the host societies. This is the true north that should guide the military’s strategic planning, capability development and global partnerships in the 21st century.

ASPI’s ‘War in 2025’ conference was held last month and attracted some leading thinkers in defence, strategy and policy.

In this episode, you’ll hear from some of them, including senior fellow at New America, Peter W. Singer, on information warfare and social media. After that, ASPI’s Huong Le Thu and Rebecca Strating of La Trobe University look at the strategic policy challenges of the Indo-Pacific, and then ASPI fellow Andrew Davies talks to our cyber analyst Tom Uren about a future force structure for the ADF, defence spending and hypersonics.

Where the ‘Indo-Pacific’ begins and ends, and what it looks like, depends partly on where you are. It’s a term that has quite subtle but different shades of meaning depending on your national or policy perspective. It is not, for example, a term welcomed by China. And the Indo-Pacific is as much a policy construct as it is a geographical reality, so how it evolves further will depend on how communities of interest in Australia and elsewhere construct and use the term over time.

The challenge for policymakers and others is deciding what the Indo-Pacific should become in the future. The relative absence of the Pacific islands in discussion of the Indo-Pacific draws attention to the need for that idea to evolve further.

Australian strategic policy towards the Pacific islands has been, over decades, quite instrumental in its focus—the islands have been seen as objects that can be shaped and used in various ways to enhance Australia’s strategic position. Offshore detention centres, to use a polite term, are a recent manifestation of this instrumentalism—the island countries are a means to our end. In this case, they’re places to put people we don’t want in Australia.

We’ve described defence cooperation in terms of understanding the environment where we might need to conduct military operations in the future, to shape police and military capabilities in ways that support Pacific island countries’ needs, but also to enable appropriate infrastructure and interoperable capability for the Australian Defence Force.

We’ve also wanted to shape defence and strategic policy thinking in those countries. Important projects such as the Pacific patrol boat program and its successor Pacific maritime security program are not only concerned with providing much-needed capability but also with building a world view about the nature of that strategic environment.

The 2013 defence white paper was the first Defence document to use the term ‘Indo-Pacific’. One idea behind the Indo-Pacific as a framework for thinking about Australia’s strategic environment was that it returned our focus to an older, more traditional framing of our strategic environment—the archipelago to the north.

That white paper, with the idea of the Indo-Pacific as an emerging strategic community, had as a central question: what sort of Indo-Pacific community can we build and how should that community govern itself? This frame tried to establish the idea that all countries have a stake in the Indo-Pacific and its future and that there was much greater benefit to all in some form of strategic order management that was rules based and collaborative.

This is a very different question from that of how the Indo-Pacific strategic system might be bifurcated between the US and China.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative is an enormous and blunt force that’s reshaping infrastructure across the Indo-Pacific and beyond, including the Pacific islands. It’s being seen as—and feels like—a crisis: a slow-moving one that’s gathering pace and is not the sort of crisis that we’ve had to deal with in the past. But it isn’t the only economic and political force operating in that region; nor is it, when one considers the intensifying effect of climate change, perhaps the largest. But it, more than any other, has heightened anxiety in Australia about our role and position in relation to the Pacific island states. A particular focus for policymakers has been the question of what it might mean for our strategic and security interests if China were to establish a military presence in this part of the world as an extension of its infrastructure engagement.

There’s a danger of responding in a way that reinforces the idea that the Pacific islands are only a site for potential great-power competition, or that they should be seen simply as being within our ‘sphere of influence’, as then–foreign minister Julie Bishop said last year. This is the policy approach that sees the Pacific islands primarily as a means to some larger strategic end, rather than as participants in a diverse Indo-Pacific community still in formation.

Australian strategic thinking needs to step beyond seeing the Pacific islands in an instrumental way and as an arena for future potential conflict. Perhaps the Indo-Pacific idea gives us the opportunity to rethink our construction of this environment in Australian strategic discourse. This might allow a more productive long-term framing of the Indo-Pacific idea in the context of the Pacific islands, along with a more expansive view of strategic challenges, such as climate change, rather than seeing these countries merely as an arena for an emerging competition between major powers.

Space has traditionally been the domain of the great powers, and the cost of space technologies has ensured that smaller states like Australia depended on those countries for satellite coverage. But that’s changing rapidly. A renewed global focus on space has led to the development of new technologies and a major shift in the way states think about space.

This new vision of space and its potential (known as ‘Space 2.0’) is propelled by commercial investment and a ‘small but many’ approach to satellite technologies. It emphasises low-cost, responsive systems and interoperability to create versatile satellite constellations. Low-cost systems have facilitated the entry of smaller states into the space domain—what’s been called the ‘democratisation of space’. The global space industry experienced a 100% increase in total spacecraft deployments in 2017, underpinned by a 200% increase in commercial spacecraft.

The effects of this booming global space industry are being felt in the Indo-Pacific (see map below). In Australia, we’ve seen the creation of the Australian Space Agency with a mandate to promote the growth of the civil industry and develop a regulatory framework. Through Space 2.0, Australia can establish itself as a global hub for space technology by supporting research and development in space-related fields, such as micro- and nanosatellites, robotics, synthetic biology and ‘leapfrog’ technologies. Because 90% of our defence capabilities rely on space technologies, our security depends heavily on our ability to leverage those technologies.

Space 2.0 in the Indo-Pacific

A trend towards indigenously produced small satellites is evident throughout the region. Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore and Vietnam have all committed to developing space technologies. Bilateral and multilateral collaboration is the driving force behind these rapid advances in space science and engineering. After collaborating with the Technical University of Berlin on its first microsatellite (LAPAN-A1) in 2007, Indonesia piggybacked its first two indigenously manufactured satellites (LAPAN-A2 and A3) on launches from India in 2013 and 2014. Indonesia has a plan to develop launch capabilities over the next 21 years and expects to launch its first indigenous rocket this year or next.

Thailand is taking a similar approach. Its Geo-Informatics and Space Technology Development Agency is partnering with Airbus to build the THEOS-2 geo-information system. Under the partnership agreement, Thai engineers will be involved in developing an integrated geo-information system, two earth-observation satellites and a ground segment. Thailand aspires to one day become a producer and exporter of small and microsatellites.

Australia shouldn’t sit on the sidelines and watch the space industry boom around it. Instead, we need to engage proactively with our neighbours.

While Space 2.0 has lowered the price of admission to space, not all states are developing their own capabilities. Brunei, Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands don’t have the resources or expertise to develop their own domestic capabilities but will still be able to use the competitive commercial industry to lower the cost of access to space technologies. This presents both an opportunity for the Australian space industry and a challenge for the defence industry.

Competition in the region is thriving. China is already exporting satellites to developing countries and signalling plans to expand the market as part of its Belt and Road Initiative. A network of Chinese communications and imaging satellites operating over the Asia–Pacific would pose a challenge for regional security. With wide coverage and significant influence, China’s assertiveness can only be expected to grow. So, Australia needs to maintain a competitive edge and take a whole-of-government approach to ensure that our national interests are bolstered, not threatened, by the growth of the space industry.

Working with our neighbours to develop satellite technologies, launch capabilities and land-based systems would help to increase commercial competition, paving the way for international space investment and establishing a more robust defence capability. To achieve that, we’ll need to invest and signal our clear commitment to the development of space technologies. The recent release of the Australian civil space strategy, which notes the need to engage in international partnerships, is a step in the right direction. However, the strategy is mostly based on engagement with established Western states and barely touches on the opportunities in the Asia–Pacific.

Space 2.0 has provided the foundations for a booming global industry in our region and offers Australia an opportunity to readjust its trajectory, step up and lead the way. If we want to bolster the security of the region through space technology and pave the way for industry, we need to pursue closer collaboration with our neighbours now, not in two, three or 10 years.

It’s now clear that China wants to become the predominant power in Asia. Why should that be a concern? The answer goes to the heart of the intersection of interests and values in foreign policy.

Becoming the predominant power would make China the single most important shaper of the region’s strategic culture and norms. So whether it is a democracy or a one-party state matters.

We are now entering a potentially dangerous period in US–China relations. The voices of containment are getting louder.

There’s nothing new about the US being determined to hang onto strategic primacy. But what is new is the suggestion that this can be achieved by blocking or thwarting China.

Containing China is a policy dead end. China is too enmeshed in the international system and too important to our region to be contained. And the notion that global technology supply chains can be divided into a China-led system and a US-led system is both economic and geopolitical folly.

The US is right to call China to account. But it would be a mistake for the US to cling to primacy by thwarting China. Those of us who value US leadership want the US to retain it by lifting its game, not spoiling China’s.

China’s rise needs to be managed not frustrated. It needs to be balanced not contained. Constructing that balance and anchoring it in a new strategic equilibrium in the Indo-Pacific is the big challenge of our time.

Most countries in the region aren’t comfortable with China becoming the predominant strategic power in the region. They don’t want to contain China but they do want to balance China; and, indeed, to constrain some its behaviour.

Already a de facto balance along these lines is in the making through the shared desire of the US, India, Japan and others to balance China. Each has its own geopolitical and historical reasons for doing so, of which the non-democratic character of China is by no means the primary driver. Moreover, this isn’t a classic balance-of-power grouping. It’s an organic, not an orchestrated, arrangement.

ASEAN as a grouping may remain on the sidelines of the strategic balance. But, with some notable exceptions, more and more individual ASEAN nations are being pulled into China’s orbit: not with enthusiasm or conviction but because they see that the economic cost of opposing China’s agenda is too high. Even Vietnam, which has a long and fraught history with China, will be constrained in how far it can go in lending support to balancing China.

The two Asian powers with an unambiguous commitment to balancing China are Japan and India. For both, China is the reference point of their strategic compasses. Geography and history pull them to the other side of the China balance. This creates common strategic ground between them and each is moving quickly to build on that foundation.

Balancing China should not involve a capital ‘A’ alliance of democracies because that would create a structural fault line in Asia and further harden China’s position. Avoiding an alliance is also a better fit with the strategic preferences of countries such as India and Indonesia, neither of which wishes to be an ally of the US or any other power. An organic balance is more in keeping with the strategic grain of the Indo-Pacific than a formal arrangement.

We are currently in the middle of a transition in international relations, and that is probably the worst time to put it into perspective. Some of what we’re seeing today are exaggerations or aberrations which are unlikely to become enduring trends. But others go to the bedrock of global geoeconomics. Deciding which is which is far from easy.

For example, it would be a mistake to see President Donald Trump as an aberration and assume that US policy will return to its norm after his departure. But equally it’s unlikely that all of his policies will survive his departure. It’s more likely than not—to take just one example—that the value of US alliances will be restored to a central position in US policy in a post-Trump world. And with China, we may well see a tactical shift in its approach as it recalibrates how far and how fast it should proceed with its more assertive foreign policy position.

Trends are like waves. We can see them on the horizon but we don’t know exactly when they will break and in what pattern they will reach the shore. We cannot, Canute-like, order them back. But we can prepare for them and think through what form we want them to take. They cannot be resisted but they can be shaped, and that is what the burden of policymaking is ultimately most about.

This article is based on a talk given at ASPI’s ‘War in 2025’ international conference on 13 June 2019.

The executive summary of the US Senate Armed Services Committee’s (SASC’s) mark-up of the 2020 National Defense Authorization Act set the stage for a number of lively discussions at this year’s Shangri-La Dialogue. While many eyes were on China, the SASC’s mark-up highlights a serious potential friction point in the maritime domain between the US and Australia, namely pledges from both states to build ‘information fusion centres’ focused on the Pacific islands.

The SASC executive summary trumpets its adherence to the US national defence strategy as its organisational framework and highlights its proposal for a fusion centre under the strategy’s ‘Strengthening alliances’ heading. In fact, this proposal does exactly the opposite by failing to recognise a key ally’s strategic interests, regional leadership and existing security cooperation relationships.

As the Indo-Pacific construct takes shape in various forms across the region, the Pacific islands are a key subregion that has been somewhat neglected, to varying degrees, by most regional powers. Australia, however, far outstrips any other in its interest and engagement in the realm of maritime security. Though 2018 saw a number of high-ranking US officials visiting the region, it appears now that those visits weren’t necessarily conducted with full understanding of, or regard for, their allies’ existing strategic equities and plans. This is where the SASC’s mark-up represents a very real opportunity for the US, a relative latecomer to the Pacific island security scene, to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory by attempting to lead a maritime security effort that already has a clear leader.

In the release, the SASC designates US Indo-Pacific Command as responsible for ‘establish[ing] one or more open-source intelligence fusion centers to enhance cooperation with Pacific Island countries’. This proposal, in one breath, presents multiple opportunities to severely hinder the development of maritime security in the Southwest Pacific.

As noted, the US proposal directly overlaps with allied Australia’s stated plans to provide the same capability within the region. Foreign Minister Marise Payne announced Australia’s commitment to building a Pacific fusion centre during the 2018 Pacific Islands Forum in Nauru. Planned as an interagency centre, the Australian construct would support Pacific island states with fusing together relevant maritime security information and communicating with partners about key regional threats such as illegal fishing, people trafficking, drug smuggling and maritime safety.

The Australian proposal would fit neatly alongside existing security cooperation arrangements, namely the Pacific Maritime Security Program, which will be providing patrol vessels and aerial surveillance to 12 Pacific island countries over the next several years. The program is the successor to Australia’s Pacific Patrol Boat Program, which provided a number of boats to Pacific island states between 1987 and 1997. It stands to reason that the nation providing the surface patrol and aerial surveillance support required for maritime domain awareness should also lead the effort in fusing, analysing and disseminating that data.

The announcement from the US represents a clear failure to respect Australia’s natural and evident leadership in the region, as well as an easily avoided failure to coordinate with a key ally.

Duplication of security cooperation efforts raises the issue of whether partners have the capacity to absorb the new initiative. Even the most capable navies and maritime law enforcement entities in the Southwest Pacific lack the patrol vessels and personnel to safeguard their often-vast exclusive economic zones, let alone participate in multiple multinational information-sharing efforts. A second, US-led centre, therefore, threatens to become a burden on the very countries it intends to help. The prospect of sending personnel to two separate, yet similar, fusion centres would likely force countries to choose between them, resulting in inconsistent participation and dashing hopes of a cohesive regional maritime picture.

Two centres competing for business will create so-called information stovepipes and limit the operational utility of both centres. The US announcement of ‘one or more fusion centers’ sounds as if American policymakers are under the impression that more is always better, which could not be further from the truth in this case.

From an organisational perspective, directing Indo-Pacific Command to lead this effort risks militarising an issue that is at its core a constabulary one. While the US Department of Defense might have ready access to more intelligence capabilities, it may not be a good fit for leading a fusion centre and engaging with a mix of small navies and maritime law enforcement agencies. An organisation like Australia’s Maritime Border Command is far better positioned and has far more credibility in the region for approaching the complicated issue of creating a multinational information-sharing construct for law enforcement in the Pacific islands region.

Unless there has been a silent withdrawal of the Australian pledge to go forward with its Pacific fusion centre concept, the US has put itself broadside into the waves with its proposal. There may still be time to right the ship, as the NDAA has yet navigate its way through the legislative process, but swift action must be taken. If the US government wants to build unclassified maritime domain awareness among the Pacific islands, it would be better served by playing a supporting role in an Australian production, for the sake of both regional maritime security and the bilateral relationship.

The 18th iteration of the Shangri-La Dialogue, the region’s premier defence and security conference, was much anticipated. The Sino-American trade dispute had stepped up with Washington imposing tariffs on a further US$200 billion worth of goods and Beijing returning the favour. Acting defence secretary Patrick Shanahan would be presenting his first major policy address in the region and the Pentagon had promised that the speech would flesh out the defence contribution to the administration’s ‘free and open Indo-Pacific strategy’. Given the increasingly hardline rhetoric of Trump administration officials towards China since Vice President Mike Pence’s Hudson Institute speech, the opening US plenary promised potential fireworks.

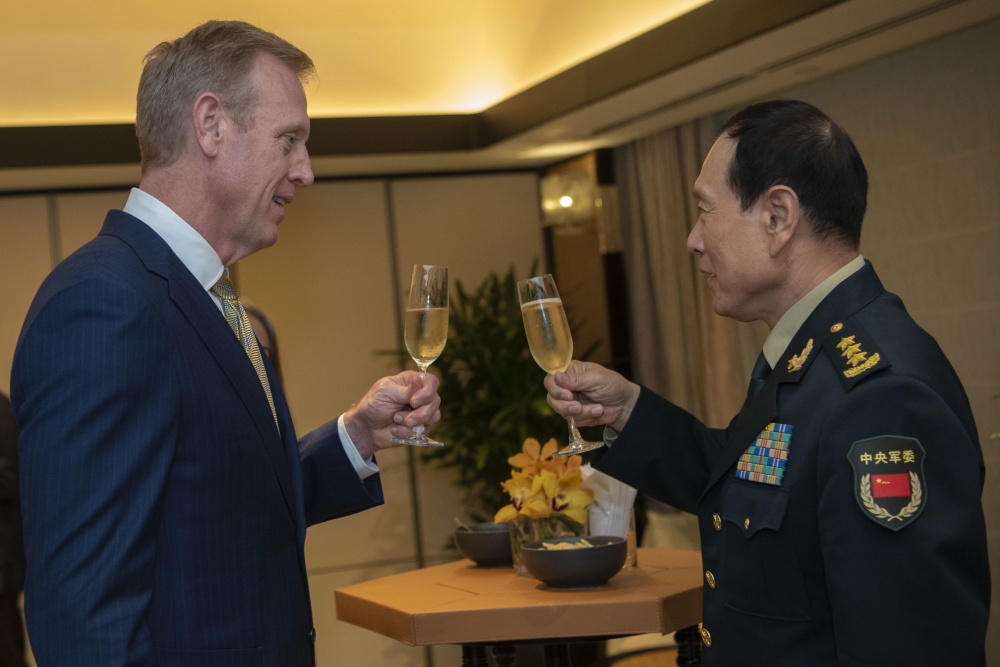

Not to be outdone, Beijing chose this year to re-engage with Shangri-La. Since 2014, when Lieutenant General Wang Guanzhong went off script and complained about an atmosphere ‘suffused with hegemonism’, China has sent low-level delegations reflecting a suspicion that the forum is rigged against it. This time it would be the defence minister going, giving Beijing a protocol edge as he technically outranked Shanahan.

In the Chinese system the ministerial role is a state position, and often just a figurehead; the real power lies with the party officials who control the military. Wei Fenghe is a general in the People’s Liberation Army and the fifth-ranking member of the Central Military Commission, a party man of genuine substance. Brendan Taylor and I anticipated that this move was part of the country’s broader efforts to position itself as a stabilising force in the region and so we thought it was likely that China would use the opportunity of the plenary address at the dialogue to pursue a strategic charm offensive.

We were expecting fire and brimstone from the US and smooth diplomacy from China but got almost the reverse. Shanahan presented a remarkably moderate, almost boring, address. It was as if there’s a template for Shangri-La addresses on some laptop in the Pentagon which is tweaked from year to year. There was nothing new added to existing policy and even the formal Indo-Pacific strategy document, which was released online as the acting secretary spoke, had little of substance that was new. And when pressed in question time, Shanahan essentially said, this time there’s money attached, about which more than a few had doubts.

While there was a subtle dig at China as he described presenting the Chinese minister with a coffee-table book of photos of Chinese vessels transferring oil at sea the previous day, referring to China’s efforts to help North Korea avoid sanctions, in contrast to the Manichaean tone of Pence and others, Shanahan was positively placatory. Indeed, in talking about areas the two could work together he held out a hand to China.

If the US was more conciliatory than we expected, the confident and indeed pugnacious remarks of China’s defence minister were even more surprising. Wei unapologetically laid down China’s vision for the region and the Chinese Communist Party’s version of its history. China was not an aggressive power, claimed the minister, never having invaded ‘another inch’ of any other country. The splutters from Vietnamese and Indian delegates could not be missed. As Ashley Townshend from the University of Sydney put it, the address asked for acceptance of China’s broader strategic claims and implied that in return it would remain peaceful.

But it was in the question session that Wei most surprised. Where Shanahan seemed uncomfortable and keen to get off the stage, Wei was unflappable, happy to address all questions and even, in a distinctly PLA way, charming. When questions came about Tiananmen and Xinjiang, alongside more straightforward questions about capabilities and a South China Sea code of conduct, he dealt with them directly. While his arguments were themselves standard party-line stuff—Tiananmen was a turbulent period, the right decision was taken and 30 years of prosperity is the proof—but seeing a four-star general recount them in the full glare of a packed hall and the international media was something to behold. The level of Chinese confidence embodied by the general was the talk of the conference halls.

What of the lesser powers? Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s keynote opening the dialogue was a deft piece of diplomacy. The fact that delegates from China and the US seemed equally annoyed by it is perhaps testimony to his ability to thread his particular needle. The unmistakable, although unstated, point Lee made was that countries in the region see China with more pragmatic eyes than does Washington. And the inability of US officials and delegates to come to terms with that fact was striking.

Shangri-La also marked the first outing on the global stage of Australia’s new defence minister, Linda Reynolds. She opened with a cringe-inducing reference to mateship, but like Shanahan presented a speech about Australian policy in the region we’ve largely heard many times before. One has the sense that Australian policy, at least in its public variant, hasn’t come to terms with the epochal changes afoot in the region. The content of the remarks evinced the victory of wishful thinking over hard strategic reality.

Shangri-La is a vast exercise in public diplomacy and as such an invaluable opportunity to take the region’s strategic temperature. With the US not using the opportunity to dial up the pressure on China, the region’s short-term future looks slightly more stable. The Washington–Beijing trade war hasn’t yet been matched with equivalent military pressure.

But viewed over the longer term, what was on display in Shangri-La’s Island Ballroom was deeply disturbing. It’s clear that China and the US have irreconcilable views of the region and their respective places in it. Neither appears able to recognise that fact or to take steps to compromise and find space for the other. For so long as that prevails, the region’s future will be increasingly bleak.

Amid growing concern about potential threats to peace in the Indo-Pacific, a Royal Australian Navy task force has completed a three-month tour of seven key regional nations.

Led by the flagship HMAS Canberra, the four ships on the Indo-Pacific Endeavour 2019 (IPE 19) operation visited India, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia on one of the RAN’s most complex and ambitious operations in peacetime. The vessels were accompanied on part of the exercise by a RAAF P8 Poseidon maritime patrol plane and a submarine.

Aboard HMAS Canberra, navy chief Mike Noonan says the operation has demonstrated to Australia’s allies in the region and internationally the fleet’s growing capability and what that means for the Australian Defence Force, and the government’s ability to operate in the region.

‘IPE 19 could be categorised as a series of goodwill visits, but it’s much more than that—it’s about deepening relationships and partnerships in the region, improving our capacity to contribute to the region and building our mariner skills and amphibious capability’, Vice Admiral Noonan says.

‘This deployment sends a very strong message throughout the region that Australia’s a very capable and committed partner, friend and ally.’

For HMAS Canberra, IPE 19 has provided a ‘soft start’ to a series of exercises which will culminate with Talisman Sabre in July. The Canberra’s sister ship, HMAS Adelaide, will also take part. ‘Those exercises will absolutely test their high-end war-fighting capability’, Noonan says.

For decades the navy had a frigate stationed in the Middle East which has seen a focus on single-ship boarding operations and there were few opportunities for the ships to work together.

As detailed in his Plan Pelorus 2022, Noonan’s goal is to ensure that the navy can conduct sustained task group operations as part of a combined force. The navy strategy says: ‘There will be an increasing focus on persistent operations in the near-region to shape and understand our operating environment, support our regional partners, and ensure our national influence and access. This will be enabled through integrated operations with Air Force and Army, increased activities with allies and like-minded partners in our region.’

All prudent navies know the operating environments in which they’ll work, Noonan says. Being active in the region is very important in terms of understanding the climatic conditions, the geography, how people operate and how the ship’s systems will function, and that’s what IPE 19 is about. But getting there is a long and complex road.

Noonan says IPE 19 is not directly related to anything China is doing in the region or around the world.

China took part in the International Maritime Security Conference hosted by Singapore’s navy during the task force’s visit and a ship from the People’s Liberation Army Navy was tied up close to HMAS Canberra.

China’s interests in the region were discussed at great length during the conference, Noonan says.

HMAS Melbourne visited China last month for the 70th anniversary of the PLAN.

‘These are opportunities for us to interact with our Chinese counterparts. I see this as being part of the regional understanding of what our navy does, and the other navies that are out there.’

During the year, Australian ships would deploy to the South China Sea and the RAN would attend the Japanese navy’s fleet review.

‘Operating in this environment is standard practice and we’re committed to continuing this’, Noonan says.

Task force commander Air Commodore Richard Owen says Australia is happy for China to be involved in the region as long as it’s operating in a transparent way that enhances trust and builds the rules-based order.

‘They’re a major world economic power with a large military and of course they’ll be involved in the region and offering regional security. Everyone else operates to that rules-based order and China needs to be part of that as well.

‘It would be foolish to push China out. We need to encourage them to come in in a transparent way.’

With an average age of 24, the ships’ young crew members brought the task force down through the Malacca Strait, among the world’s most congested waters. Owen says the experience will help them for their whole careers. ‘They’ll be better sailors for it, better navigators and better watch keepers.’

The choice of an air force officer to head the task force signalled the wish of ADF chief General Angus Campbell to emphasise the need for the increasingly high level of ‘jointness’ in ADF operations.

On the Canberra were Darwin-based US Marines and personnel from New Zealand, Britain, Sri Lanka, India and Indonesia. The New Zealanders and Sri Lankans were on board when the Christchurch mosque shootings and Colombo church attacks occurred.

While a focus of the trip was on humanitarian and disaster relief operations, it can’t have been lost on anyone that the flagship carried four of the army’s Tiger armed reconnaissance helicopters from the 1st Aviation Regiment.

The Tigers were not part of IPE 19. The army fliers were there to take advantage of the extended time at sea to qualify for deck landings by night and day and in varied weather conditions.

That said, the Tigers are armed with Hellfire missiles, rockets and a 30-milimetre cannon, and the aviation regiment’s commander, Lieutenant Colonel Dan Bartle, says they could protect the amphibious force when it was going ashore aboard transport helicopters or landing craft.

But it could also defend a task force in coastal waters from threats such as fast attack craft. ‘Fifty knots is fast for a boat but not particularly fast for a helicopter’, Bartle says.

That could be as part of a humanitarian mission to rescue Australians trapped overseas in a security crisis, or a major combat operation.

Despite years of problems getting the Tigers operational, their pilots say they have matured into very capable combat aircraft. They ‘go like Greyhounds’ and they’re very well suited to the ship.

It’s telling, too, that the helicopters were flown to Malaysia on the RAAF’s giant C-17 transport planes. They were assembled there and were then flown out to HMAS Canberra.

Procedures have been worked out over two years by test pilots and the first operational army pilots qualified to fly off the ship on this extended voyage.

The pilots are also trained as forward air controllers and could use their laser targeting systems to direct fire from ships, land-based artillery or aircraft onto enemy positions, Bartle says.

‘With the Tigers on board, the landing ships can carry out a whole range of additional missions with greater security.’

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria