Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Behind the recent spat between Defence Minister Richard Marles and his senior Defence advisors lies a hidden issue: are the governance arrangements for Defence’s high-level decision-making fit for purpose or do they need to be reviewed and brought up to date?

There have been many Defence ‘reviews’ over the past five decades, some more consequential than others. The Tange reforms of the early 1970s changed governance arrangements both to integrate the previously separate service and Defence departments and to ensure the implementation of the government’s new defence of Australia policies. These changes had lasting benefits.

Many of the subsequent reviews concentrated on reducing costs and increasing Defence’s reliance on industry, as well as pursuing the elusive goal of fewer errors in defence procurement.

There have been two major external reviews of the development and interpretation of policy: the 1986 review of defence capabilities, and the 2023 defence strategic review (DSR). In both cases, inadequacies of governance contributed to the need for this outsourcing.

Several post-Tange reviews have also changed governance arrangements, the most recent being the 2015 first principles review. But this work was undertaken years before there was any serious response to Australia’s deteriorating strategic circumstances, as eventually set out in the 2020 defence strategic update (DSU) and as amplified in the 2023 DSR. This gap alone would be sufficient reason to suggest that Defence’s governance arrangements should now be re-examined.

In addition, however, there had been concerns that Defence had not been sufficiently responsive to earlier stages of the worsening of Australia’s strategic outlook—ASPI Insight paper 123 of November 2017 and Strategic and Defence Studies Centre paper of October 2018. And while the 2020 DSU showed a welcome recognition of the new strategic challenges and included important new initiatives such as long-range precision-strike missiles and remotely-operated combat platforms, subsequent implementation of the new policies has been slow, as set out in some detail in the 2023 DSR.

In brief, there are good reasons to believe that today’s Defence governance arrangements need to be improved. Let’s look more closely at some of the evidence.

The decision to drop the SSK program and to go instead for SSNs represented a major change of course. Why was the original decision so wrong as to need such disruption to a vital and costly capability?

The new plans for the Navy’s surface combatant fleet also represent a major change of direction. Again, why were the earlier decisions on this matter so evidently off the mark?

Why did the DSR conclude that it is necessary to transform the Army (para 8.28), and to reduce the number of infantry fighting vehicles from 450 to 129 (para 8.35)? Is there a structural problem with how Defence considers land-force development? If so, the problem goes back a long way, to the Tange reforms, as it was the inadequacy of Defence’s processes for reviewing the Army that contributed to the need for the 1986 defence capability review.

Why is it that the ADF as currently constituted and equipped is not fully fit for purpose (DSR page7)? Why don’t we already have the ‘sense of urgency’ that the DSR advocates (para 1.9)? Why is there this ‘surprising lack of top-down direction’ for projects entering the Integrated Investment Program (DSR para 12.2)? Why has there been ‘little material gain’ in the guided weapons program over the past two years (DSR para 8.73)?

The DSR’s terms of reference required it to outline the needs for mobilisation, yet it makes only passing reference to this in its public report. Why is this? Is it too embarrassing to be discussed in the open?

Why did the DSR need to emphasise the need for genuine whole-of-government coordination of Defence policy (page 8)? Surely this is a blinding statement of the obvious.

Each of these cases in isolation could be shrugged off, and it’s important to recognise that to seek perfection would be a fool’s errand. But taken together they show that the governance problems are serious.

So much for the symptoms. From the outside we can only speculate as to what has led to this. Are the catalysts for change too inhibited or inconsequential? Is there too much emphasis on consensus? Is robust argument actively discouraged? Is the strategic policy area just too small for the workload, or too easily ignored, especially in the vital task of providing top-down guidance for capability development? Are the military staff also overwhelmed by the workload? Is there a fear that if you rock the boat you will stunt your prospects for promotion?

It’s all too easy to criticise from the sidelines. And in any case, it’s important to acknowledge that much of what Defence does is excellent and that the 2020 DSU swept away the complacency of earlier years. Further, it’s not clear how many of the problems lie with Defence rather than with the machinery of government more generally or with ministers themselves.

Overall, however, it’s clear that governance needs to be brought up to date. As things stand, neither the ADF nor the governance arrangements that guide and support it are capable of much more than peacetime operations. Whether the needed improvements would best come through internal or external review is open for debate. At the very least, in our new strategic circumstances, any proposals for change should keep in mind the first Recommendation of the 1997 defence efficiency review: The Defence Organisation should be organised for war and adapted for peace.

A leading business guru of yesteryear once observed that management was ‘doing things right’, while leadership was ‘doing the right things’. But what do you call it when you’re doing both?

This is an important question in context of the findings of a new report into industry capability and capacity in the Northern Territory.

The report, released in October by Master Builders NT and developed in partnership with ACIL Allen, is titled ‘Billion-dollar partnership’. It takes a deep dive into the ability of the NT’s construction sector to deliver the large infrastructure programs being driven by the Australian and US defence organisations while continuing to meet local demand. The two previous reports on this topic were titled ‘Capacity to spare’, which sent a very clear message about their conclusions.

Whenever there’s a major surge in demand in any sector in remote Australia, the first questions are always the same: Can the industry handle it? And if the challenge proves too big, what impact will that have on the cost, timing and success of major projects?

The intensity and scrutiny of those questions reaches even greater heights when the industry sector in focus is construction. Unlike much of the rest of the economy, construction is a self-organising and temporary economic activity. It involves a deep hierarchy of firms with an incredibly broad set of skills, but the temporary nature of its activity is the real reason for so much scrutiny.

The capability and capacity for the construction sector to meet new demands are a function of many things, including other demands in the market, the attractiveness of the work, the risks associated with the contract, and the scope for flexible resources such as labour to be scaled up or redirected.

The ACIL Allen report is an attempt to pull of all those elements together to give project proponents, the NT government and local industry a platform to work through these challenges.

It predicts more than $6 billion of demand for construction services from the defence sector alone through to 2027 (the time horizon of the report). This is a significant surge, but well within previous peaks of the local construction cycle.

Crucially, it suggests that an additional 7,600 jobs will be created, directly in construction and indirectly across the wider economy, by this work. It also breaks down the occupations that will be in greatest demand.

One objective of the analysis was to find the ‘outer boundary’ of the demand curve for construction services, examining capacity against the most optimistic scenarios to test the limits in the market.

This approach showed that if the most optimistic scenario were to unfold, gross state product—a measure of the overall size of an economy—would be almost 5% larger.

This was a finding certainly not missed by NT Chief Minister Natasha Fyles when launching the report.

The report addresses the policy settings needed to manage the surge in demand. It recommends that project proponents signal their intentions to the market as early as possible and consider adopting a ‘program mindset’ to avoid switching demand on and off in an uncoordinated fashion.

It also recommends that the government facilitate a central coordination and information-sharing mechanism between itself, the Department of Defence and the local industry’s leadership.

Other policy recommendations include that a workforce strategy be developed for the construction sector and that the NT government review its migration settings, develop a new post-Covid-19 population strategy and address housing shortages.

The word ‘partnership’ in the report’s title was a deliberate decision, according to Master Builders NT. The work that went into the report was funded by the local construction sector because companies understand the benefits of concrete conversations about capacity and capability. In addition, the data on which the report relies was available because of the good relationship between industry and Defence.

Likewise, both the NT’s official defence advocate and major projects commissioner aligned behind this work. And then there were the retired industry experts who collectively brought their extensive construction expertise to the table, allowing high-quality analysis of the limits of what the industry can achieve. It’s clear that this project is much more than the sum of its parts.

And maybe that’s the answer to the original question. Doing the right things and doing them right makes for a partnership that over almost a decade has delivered genuine leadership on coordinating major demand surges in northern Australia. And through three reports, the quality of that work just continues to grow.

Even so, every report is just a starting point for the work to follow. The challenge for this one is to get the delivery right. Local industry and local communities, along with taxpayers, rightly expect it.

ASPI’s annual conference takes place on 14–15 September at the National Convention Centre in Canberra. The theme is ‘Disruption and deterrence’.

Effective deterrence, built upon a strong Australian Defence Force that works closely with allies and partners, will be a vital part of ensuring a sustainable strategic balance in the Indo-Pacific. The simultaneous disruptive power of rapid changes in technology carries risks and opportunities for Australia and its partners as they invest in superior capabilities and look to integrate them into a seamless force.

The conference will bring together Australian government ministers, senior defence officials, leading industry figures and international experts to tackle these challenges and explore key trends and areas of innovation.

In keeping with the conference theme, The Strategist is publishing the second of two pieces by Jeffrey Becker, leading futurist for the US military. ‘Defective control’ is a fictional account of a naval clash in the Pacific in the 2030s. It aims to illustrate the potential of reusable rockets, directed energy and space capabilities—in the hands of adaptive and innovative people—to win a fight on earth. Hyperlinks are embedded throughout the story to illustrate how some of the ideas are already being put to use.

Aboard USS Miguel Keith—4 March 2036, 0900 hours

‘It’s not often you get to be around for the birth of an entirely new kind of warship,’ Captain Snyder thought as he looked down from the bridge of the USNS—well, now USS—Miguel Keith. The ship was ungainly, a thin deck perched atop steel pillars. Below was an open but very busy hanger. Above, the narrow flight deck was littered with a forest of blunt, stubby missiles standing tail-first on squat landing legs. Looking like an unfinished construction site, the flight deck was flanked by cobbled-together cranes and gantries welded to each side of the ship, giving the Keith something of the appearance of a gigantic fishing trawler.

USNS Miguel Keith, before conversion to a rocket carrier (designation CVR-1). Source: US Navy/Wikimedia Commons.

From the bridge, Snyder watched the peculiar, alien dance playing out on the Keith’s deck. Sailors, many in powered exoskeletons, were pushing and shoving a dozen AMR-1 Anvils around the deck, preparing for flight operations. ‘AMR’ designated the US Navy’s new ‘attack missile—rocket’ weapons.

AMR flight ops felt completely unlike the aggressive, low-slung—and decidedly horizontal—operations one would expect of sharp-nosed jet fighters on a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier. Instead, Snyder watched a study in the vertical. Below the bridge, he saw a complex dance of what appeared to be mobile Greek columns that were, in fact, 50-foot-tall rocket boosters.

Half a dozen of the Anvil rockets were lined up, ready to be secured by one of the many jury-rigged cranes and gantries. The gantry tipped an Anvil horizontal, dropping it to the lower hanger deck to be armed and fuelled.

‘She’s ugly, all right. But lethal doesn’t have to be pretty.’

The busy ship spread out before him was the centrepiece of a new kind of fleet. The Miguel Keith and the other expeditionary mobile base ships were originally designed as forward lily pads to support air and amphibious operations over the shore. In this war, however, they were pressed into service in an entirely new role.

They might just give the United States an edge as the war with the Chinese Communist Party moved into a new and more dangerous phase.

‘We’re going to need to think very differently if we’re going to get back in this fight,’ Snyder thought.

Twin sharp supersonic cracks interrupted his thoughts. Snyder looked up. Two Anvil boosters plummeted tail-first from the edge of space. Snyder watched them as they fell, comet-like, fiery streaks marking their path back down towards earth. At 300 feet, four spider-like legs unfolded downwards as a bright purple needle of fire spit out from the centre engine for the retro burn. Shock diamonds in the exhaust underscored the massive power of the Anvil boosters as they settled gently and almost simultaneously onto the deck of CVR-2 Montford Point two miles to port.

In the distance, rolling seas gave way to a bright blue sky. Snyder took in the view beyond the missile-studded deck of the Keith and the ongoing recovery operations aboard the Montford Point. From the bridge, the whole of Joint Task Force 216 was in view. The motley fleet was cruising deep in the Pacific Ocean north of Wake Island. Spread out over just a few miles, three new CVRs were joined by LHA-7 Tripoli, a large-deck amphibious assault ship that was also pressed into service as an Anvil-carrying warship. The four attack ships were huddled around CVN-80 Enterprise in a formation far more compact than the navy’s former aircraft carrier fleets.

Snyder looked across the bridge wing as the Enterprise pulled alongside the Keith just a few feet away. The Enterprise was hastily brought to San Diego after the Ronald Reagan and Gerald Ford were nearly sunk.

‘We’re probably going to change “CVN”, too,’ he thought. The Enterprise wasn’t really an aircraft carrier anymore, its role far different—but no less important—from when it launched fighter aircraft from its deck. Now, its nuclear power plant was pressed into service manufacturing the massive quantities of liquid oxygen needed to fuel each Anvil attack rocket.

‘Sir, ready to start UNREP,’ the XO called out.

‘Go ahead,’ Snyder replied.

With this command, minivan-sized quadcopters lifted off the deck of the Enterprise carrying with them deep-cold cryogenic refuelling lines. The quadcopters shuttled back and forth between external valves on the side of each ship, automatically and precisely connecting the liquid oxygen and methane lines and allowing each to flow from the Enterprise to the Keith.

As the replenishment proceeded, Snyder looked hard at the repurposed aircraft carrier. The Enterprise was really more than just a refueller and held another surprise for the enemy. Catapults, arresting gear and combat aircraft were removed, replaced by a dozen large, white domes. Topside, the ship looked like an astronomer’s telescope farm. Some of the domes were open, revealing large optical mirrors and devices inside. Instead of gathering light from faraway stars, Snyder knew that these ‘telescopes’ concentrated megawatts of power into targets. Each was a long-range laser ready to intercept and destroy incoming attacks from air and space with speed-of-light, nuclear-powered precision.

In the centre of the deck, a much larger dome stood above the laser arrays, nearly the full height of the Enterprise’s island. It was faceted and a metallic dark grey colour. Inside, Snyder knew, lay a massive, multidirectional grid of phased-array slabs, able to attack and destroy electronic systems over dozens of miles. This electronic warfare system was also nuclear powered and was—he hoped—strong enough to fry the electronic guts out of any missile, aircraft or ship unwise enough to approach.

Instead of spreading the fleet out, Admiral Lane kept the CVRs in tight formation with the Enterprise, which provided high-density laser and electronic fire to fend off missile-borne aerospace attacks. Precisely hitting a moving target at long range depends on precision electronics and optical systems, which are fragile. Nor can the complex and fragile control surfaces on the aircraft and missiles themselves be armoured enough to defeat high-power laser attack. The Enterprise would exploit that and put up a protective bubble for the CVRs while closing on the Chinese coast.

Snyder believed that if the People’s Liberation Army could locate the fleet, they would attack with cruise and air-launched ballistic missiles, shot from the new and stealthy long-range H-20 bombers. Getting targeting right at this range would be tough for the PLA Air Force. China’s long-range anti-ship ballistic missile force was sidelined by the orbital blockade that had stopped most space-based surveillance data from getting through. Even now, the Enterprise was attacking overhead Chinese satellites with laser and electronic fire, contributing to the US Space Force’s orbital blockade.

Snyder’s ‘fishfinder’, the onboard personal comms devices every sailor carries, squawked at his belt. A display floated at eye level. It was the admiral. Snyder gestured at the holo, answering the call.

Admiral Lane’s quiet voice came over the line. ‘Captain, could you meet me down in the print shop? I’d like to talk to you privately. I’d appreciate your take on something.’

‘Yes, ma’am. Ten minutes?’ The admiral agreed, gesturing to her own fishfinder and cutting off the connection.

Snyder wondered what the impromptu meeting was all about, and more, how the admiral managed to project calm determination in a world that was about to explode.

Operation Posui Lian (Shattered Chain)—1050 hours

Admiral Zhao’s fleet charged east, a mirror image opposite Admiral Lane and her own hidden fleet. The massive vessels under his command were heading away from their assembly area southeast of Shanghai. Zhao’s flagship, the aircraft carrier Guangdong, along with its protective screen of cruisers, destroyers and submarines, had until recently been supporting army operations on Taiwan. However, the Central Military Commission had called the force back to Ningbo to rearm and refuel, adding more combat power in the process—much more—for an ‘operation of even greater consequence’.

Admiral Wei, the fleet political officer and Zhao’s equal and counterpart in all decisions, stepped to the centre of the Guangdong’s command information centre. Zhao knew that the PLAN was not really a ‘Chinese’ navy, but rather an armed wing of the CCP. As such, every ship was led by both a commander and a political officer, as were the fleet itself, ensuring that key warfighting decisions were in line with the CMC’s party directives.

This was natural. What was less natural was Wei’s taking over the situation brief from the intelligence officer.

‘Must be important,’ Zhao thought. ‘Wei must be delivering something straight from Beijing.’

Wei turned to the holo display projecting up from the floor in the middle of the room. The Guangdong’s combat information centre was arranged in a circle around the central display. The whole of the PLAN’s East Fleet commanded from here.

‘As you know,’ Wei began, ‘Taiwanese defences are crumbling. The war on the island is moving to a new phase as the army moves on Taipei. Splittist forces are still fighting in and around the city, but our army and rocket forces are breaking the remaining resistance. The chairman anticipates the imminent success of these operations due to an extremely favourable and improving correlation of forces on this front.’

Wei gestured to the 3D display. Units from both sides floated by as the Warbot battle command system rapidly calculated Taiwanese battle positions and anticipated future movements and engagements, including the probability of success. Warbot did this in near real time, anticipating branches and sequels, and making recommendations to the human commanders.

‘As you can see from the data, this fleet’s combat power is no longer needed on Taiwan. Instead, I am pleased to inform you that we have a new mission. The objective of this mission is only within reach because of the swift and decisive successes of this fleet.’

Wei paused as the holo imagery moved outward into the central Pacific. ‘The Guangdong, together with the rocket force, delivered decisive blows against the US Navy. Our space assets have caught several glimpses of the fleet. We know the Reagan and the Ford were each struck by waves of our long-range missiles near Guam and are either sunk or on fire. Several destroyers have also been sunk. What remains is limping back to Honolulu. Social network analysis run through Warbot predicts that they have sustained over 4,000 casualties in the initial assault.’

Another pause. ‘Our attacks were far more successful than even Warbot anticipated. We re-ran our models with these updates. Warbot gave us some very surprising results.’

Wei scanned the room, filled with commanders, captains, admirals and political officers charged with operating the great fleet.

‘Comrades,’ he said, ‘with the bulk of US combat power pushed out of reach of the mainland, the party has assembled this armada to break the oceanic chain that surrounds us once and for all and instead use it to hold Japan and the Philippines in our own grip. With the Ryukyu Arc and Northern Luzon in hand, we set in motion the final stage of our great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation, communist party leading.’ A cheer went up from the assembled crowd.

Zhao listened, examining the map as Wei spoke, eyes following the long string of islands that loomed just 150 miles to the west. The founder of the modern PLAN, Admiral Liu Huaqing, spoke of these islands stretching from Japan to Singapore as a steel chain that shackled China to Asia, blocking it from its rightful place on the global stage.

‘Time to think bigger,’ Zhao thought.

Wei continued. ‘The CMC fully embraces Warbot’s conclusion that the bulk of US combat power in the Western Pacific has been damaged beyond repair. I’ll admit to being surprised. I suppose our situation is much like that of the US military after its stunning success in the first Gulf War. That success was, ironically, the impetus for this very force, a force fine-tuned to dominate information- and AI-based warfare. We will build on this success, and now execute Operation Shattered Chain.

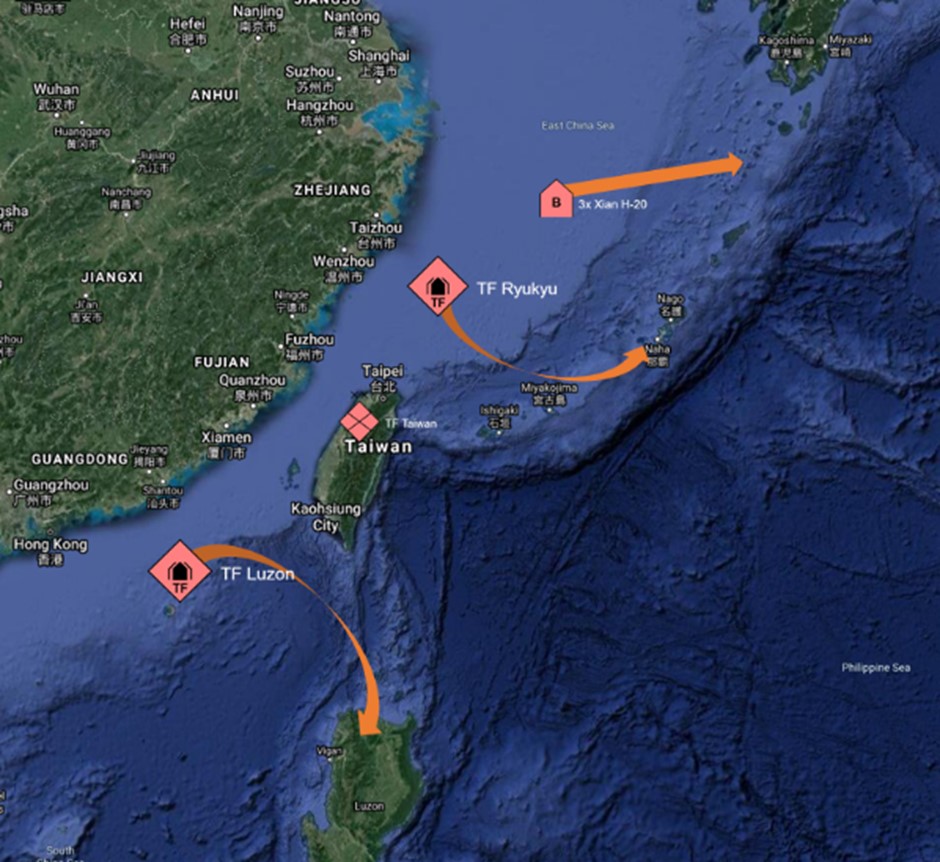

Operation Shattered Chain. Source: Google Maps, annotated by the author.

‘Shattered Chain will consist of two independent task forces, Luzon and Ryukyu, aimed at seizing the northern and southern anchors of the first island chain. TF Luzon’s objective is to seize a strip of Luzon and its offshore islands to drive off the US Army’s Multidomain Task Force. This force is currently impeding our access to the South China and Philippine Seas. Our own element, TF Ryukyu, is designated the main effort. Our objective is the seizure of entire of the Ryukyu island chain, with our initial target the seizure of the US base on Okinawa itself.’

Zhao looked on as the projected operation unfolded on the display. The Warbot AI’s confidence indicators glowed green above the unit and engagement icons as they moved, denoting a very low risk for each manoeuvre. To Zhao’s eyes, Okinawa and the rest the island chain turned a very satisfying shade of red as they fell under PLAN control.

Wei seemed very pleased by the chain of events plotted out by Warbot. All PLAN admirals, Zhao included, placed great faith in scientific precision and the use of calculations to reveal the true nature of warfare. Warbot enabled commanders to predict the course of events if they just looked hard enough, accelerating warfare faster than the enemy could adapt. Massive amounts of data, huge processing centres and powerful, networked battle AIs like Warbot brought all these calculations into reach at inhuman speed. Central Military Commission planners embedded intelligent systems throughout the PLA’s command-and-control structures, certain that Warbot would spit out the mathematically correct answer.

Events over the past months appeared to bear out Wei’s overweening confidence. The PLA’s command systems, pulled together and amped up with AI, had been delivering blows from China to Guam, from space to the electromagnetic spectrum, faster, harder and with more coordination than even he, an experienced military commander, had ever expected.

Still, Zhao was uneasy. Had China really unlocked the secrets of war that had eluded the great commanders? Even great commanders were surprised sometimes. Was Warbot that much better?

‘Secretary,’ he addressed Wei. ‘I understand the new mission. May I ask a question? I have a concern I’d like to share with this group.’

‘Go ahead, Admiral,’ said Wei, looking a bit nonplussed by the question after the delivery of his speech.

‘Comrade,’ Zhao said, ‘I’ve seen something that bothers me, something not well represented in the Warbot assessment. Our sensors are very spotty over the Central Pacific, but at least one piece of data is very strange. Radar and infrared have detected several bright and fast-moving targets at very high speed. Probably at least one rocket body. However—and this is what I don’t fully understand—instead of coming at us directly, it tipped upward at the edge of the atmosphere and started falling back to earth, moving east, rather than in this direction. This doesn’t follow any known flight profile for US long-range weapons.’

‘Admiral,’ Wei said, cutting him off. ‘It sounds like either a failed submarine attack or perhaps a feint.’

‘Interesting,’ Zhao thought, the tiny fissure of doubt widening. He knew that the IR and radar returns were only part of the story. Sensor data sent from the Strategic Support Force told him that just before the tip-up, the missiles ejected at least 16 small vehicles each. Those also fell far short of the fleet, just east of Okinawa. Not dangerous, but it was still a concern and left him unsettled. The launch location, the flight profile of the twin rockets, and the fast-moving vehicles falling short—none of it was right.

‘Yes, that is probably the case,’ Zhao said agreeably, not wanting Wei to lose face in front of his command. However, he resolved to take a closer look, running these observations through Warbot to see where they might lead.

Contact—1120 hours

Aboard the Miguel Keith, Captain Snyder met Admiral Lane below decks. They walked together through the printshop, examining stacks of gleaming 10-foot-long shards of 3D-printed metal. Each was an independently targetable munition and they would be loaded 12 at a time atop an Anvil booster. The printers allowed intricate hypersonic scramjet-powered engines to be grown, inside out, aboard the ship. As if they were on some steampunk coal-fired warship, exoskeleton-clad sailors shovelled titanium alloy powder into hoppers feeding the machines. On the other side, sailors in forklift-sized powersuits lifted the shards as they were spit out of the printer, stacking them with the others, steaming as they cooled.

The two walked side by side, silently examining the newly made weapons. It was hot in the print shop—the titanium had to be heated to 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit. Hopefully the whole system would one day be automated. For now, sailors in the heavy, but weirdly graceful, powersuits moved the shards between the printers, an assembly area where they would be fitted with an electromagnetic-pulse-hardened electronic brain and radar and optical sensors, and then mated to a fuelled-up Anvil to be hurled at the enemy.

But the robotic systems would have to wait for now. Snyder and Lane paused, examining one of the newly printed shards. Someone had painted ‘With love, from Honolulu’ on it. ‘Nice touch,’ Lane remarked. Of course, the art wouldn’t last long, vaporising the moment the shard hit the atmosphere after being ejected from an Anvil’s aeroshell.

‘Captain,’ Lane said, breaking the silence between them. ‘What do you think Zhao’s fleet is going to do next?’

‘Admiral, the PLAN is now—by an uncomfortable margin—the largest naval force on the planet. If I were them, I would cross the East and South China Seas as fast as I could and seize and fortify the first island chain. They’ve got to be feeling pretty pleased with themselves. For them, another easy roll of the iron dice puts everything from Kyushu to Luzon in their grasp. Hell, I might not stop there. From their perspective, there’s nothing between them and Guam. Maybe even Midway and Hawaii.’

‘I agree. Where do you think they’ll go first?’ Lane asked.

Snyder said, ‘I think the PLAN is assembling a northern fleet here.’ He gestured to a large-scale map of the Western Pacific projected from his pocket holo display. A satellite view swept inward, zooming in from space and focusing on a massive assembly of over a hundred ships. The high-resolution imagery of the ships hung in the air in front of them.

‘When was the last time you had a good look and updated this?’ asked the admiral.

‘About six hours ago,’ Snyder responded. ‘Too long ago to get a good firing solution.’

Lane turned to Snyder, gesturing to push a data packet to Snyder’s fishfinder. ‘Take a look at this. We got a very good look from those two scout-configured Anvils that just came back.’

Snyder was surprised at the diverging trajectories of the two Anvils. Each dropped off a swarm of high-endurance sniffer drones. The first was expected: deploying stealthy drones to stalk the northern fleet. Snyder had wondered why the admiral had risked the discovery of JTF 216 by launching the Anvils. But now he understood.

‘You sent the second Anvil south.’

Lane nodded. ‘Since two reconnaissance shots would be just as detectable as one, I had the Montford Point look to the south as well. The Multidomain Task Force has been hitting a lot of Chinese hardware coming south and east. It’s got to be giving them headaches. If it were me, I’d spare a force to clean them up.’

Snyder’s eyes widened. ‘Did you find it?’

‘Yes. Targeting quality. I want you to get your AI working on an attack-management plan immediately. But first, I want your take on how fast we can turn around an Anvil alpha strike force. Can we get a second strike in the air quickly?’

‘Admiral, the short answer is, two hours. However, I don’t think we’ll need a follow-up strike. I think we can put enough Anvils with enough shards on the northern fleet to put most of them on the bottom, or at least make them think twice about trying for Okinawa. I’d recommend getting our licks in, recovering the Anvils and retreating beyond H-20 range to preserve the fleet to support the task force when we can really reset. This second set of Anvil data should really help them out.’

Lane looked across the hanger as the sailors continued stacking the shards. She was thinking. Her eyes stayed on the stacks and narrowed. ‘I don’t intend to hit the northern force twice. I intend to kill both fleets—northern and southern. Today.’

Raid—1250 hours

The general quarters alarm broke the fevered preparation throughout JTF 216. The Miguel Keith had already detached from the Enterprise, but it was still close. Overhead, a Chinese Dark Sword drone was screaming by the fleet. The high-speed reconnaissance drone was detected by the Enterprise, which quickly smashed the control computer with a high-powered microwave pulse, sending it crashing into the sea. However, the electronic attack wasn’t fast enough to stop a data burst transmission to three H-20 stealth bombers on combat patrol north of Task Force Okinawa.

The H-20 flight command Warbot received the message, analysing the data in milliseconds and beginning on-board mission attack planning. Within seconds, Warbot had identified the contact as the Enterprise and assessed the five-ship formation as a critical strategic strike priority. The lack of air-defence destroyers in the formation was highly irregular, but this fact pushed the assessed probability of a kill for a combined attack on the Enterprise at close to 100%.

Before the human flight lead understood what was happening, the three aircraft turned sharply northeast with pinpoint precision. The bombers straightened, pitched slightly upward, and the bomb bay doors opened and simultaneously dropped six air-launched ballistic missiles in rapid succession. The missiles fell away several hundred feet before the rocket motors ignited. The aircrew watched as the missiles sped away, arcing high above the bomber formation at Mach 5, only now made aware of the nature of the target after being alerted by Warbot to return home.

The Enterprise’s high-altitude aerostat, cruising alongside the fleet at 100,000 feet, caught the bright infrared signatures of the missiles and passed the data to the Enterprise. An automatic alarm sounded in all the ships of JTF 216: ‘Crew alert. Six vipers inbound. Laser operations commencing momentarily. Don eye protection immediately.’ Snyder reached below his command console on the bridge and put heavy goggles over his eyes, as did everyone else in the fleet.

Aboard the Enterprise all 12 laser domes opened and snapped to the southwest. Invisible beams immediately crossed the 20-mile gulf, striking the inbound missiles almost instantaneously. Occasionally a beam would cross through cloud and sea spray, splashing high-intensity flashes of light around the fleet and blanketing the sky like a silent lightning storm. The beams found the missile bodies, heating up and warping the metal just enough to cause the weapons to tumble and break apart, pieces careening and cartwheeling into the sea.

Lane, connected by line-of-sight lasers to Snyder and the other ship commanders, came up on the battle network. ‘JTF 216, the enemy is aware of our positions. You have your targets. Fight these ships and destroy the Chinese fleet,’ she said.

Alpha strike—1332 hours

Lane delivered the order from the bridge of the Miguel Keith and flight deck operations began in earnest. Snyder was busy monitoring the complex movements of the Anvils to get them off the deck as close together as possible. Within seconds, eight rockets roared off the decks of the CVRs, two apiece, climbing skyward. Robotic grabbers moved two more rockets into position on each ship. Wave after wave of missiles leapt upward from the deck, the sequence repeating until each ship had had put 18 boosters into the sky.

The admiral looked up as her four ships threw 72 Anvils configured to deliver a shower of 864 half-ton, independently targetable shards at Zhao’s force. At Mach 8, the shards would cover the 2,500 nautical miles in under 20 minutes. Streaking upwards in minutes to the edge of the atmosphere, the Anvils spit out the shards, which immediately snapped away in many different directions. As the Anvils rose, the onboard AIs coordinated trajectories for each grouping and commanded the shards to converge on TF Okinawa in two waves less than two minutes apart.

As the first wave of shards descended, they began scanning Zhao’s fleet, each shard picking out the most lucrative targets and coordinating with the other weapons to focus on the air-defence ships, ensuring the second wave would get through. The emphasis on air-defence ships would turn out to be unnecessary. Zhao and Wei had placed Warbot in full command of the automated defence systems, but the highly manoeuvrable shards moved too fast and unpredictably to be intercepted.

The result of the first wave was catastrophic. Multiple shards punched all the way through the ships from top to bottom, setting fires and detonating ordnance. Just before impact, the first wave passed data to the second, allowing them to pick undamaged or high-value ships and to maximise damage to the remaining ships.

Back at JTF 216, Snyder heard a sharp succession of supersonic cracks as the Anvils returned from the strike. As they again landed tail-first, squat, crablike robots scuttled across the deck, attaching to the base of each returning rocket. Lifting the Anvil slightly, the bot moved the missile out of the way to the side gantries, which tipped the rocket horizontally.

With surprising speed, the gantry dropped the rocket to a cradle on the lower deck. The cradle slid into the ship, where weapons techs waited in their exoskeletons, sliding a new bundle of shards into the Anvil’s forward conical fairing. Locking the warheads down, the tech swept an exoskeleton-clad arm forward, moving the rocket to the opposite elevator, while the cradle slide outward to receive the next Anvil to rearm and refuel.

Anvils, reloaded and refuelled, began leaping off the decks of all four ships once again. This time, they headed for the smaller task force aimed at Luzon.

The aftermath—11 November 2043

Retired admiral Zhao took the interview via holo from a reporter in now-independent Hong Kong.

‘Admiral, thanks for joining us. This is the first time we’ve had someone at your level talk about the PLAN experience during the Great Pacific War. Can you reflect a bit for our audience on the disastrous Battle of the East China Sea?’

‘Thank you for the opportunity. It’s very gratifying to tell this story. As you well know, that engagement turned the tide of the war and ultimately sent the Chinese Communist Party to its grave.’

Zhao paused.

‘The missile assault that sunk not one, but two fleets is well known. What is perhaps less well known, but was really the most important factor in our defeat, was the great stock we placed … well, our utter fixation, actually, on our ability to hammer the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, its escorts and all its means of support far out to sea. We knew our rain of missiles would send the US Air Force fleeing Japan eastward. We worked through scenario after scenario with Warbot, predicting victory after victory. We had built a symphony of destruction we were sure would give us a firm grip on the first island chain and beyond.’

‘But ultimately, Warbot didn’t work?’ the reporter asked.

Zhao paused again and sighed.

‘The party, in true scientific-socialist fashion, calculated everything the Americans would do. Everything except the new missile ships. Those were a surprise.’

‘But why did missing just a few ships used in this new way cause your plans to unravel?’

‘For all of our centralised, automated and AI-based force planning, we couldn’t control an adaptive, motivated America that could respond and strike out in an entirely new way.’

As the interview continued, Zhao recounted the long war that dragged on over the next four years, with over 100,000 dead and wounded on each side and more than a few nuclear near-misses along the way.

‘By that time, we should have known that bad information ultimately would lead to disorganisation and chaos. But even after the twin calamities off of Okinawa and Luzon, we couldn’t adapt. Our confidence that we understood modern battle was broken shell that would never recover. The worst part for me was that we clung to our mistaken beliefs, standing by, waiting for Warbot to give us the right answers, replacing our own judgement and experience with those of the machines.’

Public discussion of the defence strategic review (DSR) has focused on the announced changes to major capability programs. On that score, the statement by Defence Minister Richard Marles that the DSR is ‘the most ambitious review of Defence’s posture and structure since the Second World War’ is hard to reconcile with its recommendations, as there were few specific changes beyond those to Army which had been long expected. A few short paragraphs on the way that Australia should fundamentally change its approach to defence planning and force design, however, hint at very consequential change—and it is important that the government does not lose sight of their importance, despite them not receiving an explicit mention in the minister’s statement.

Australian defence white papers tend to consist of an engaging essay on the strategic environment in the front, and a list of capability decisions at the back. In general, the links between both are always implicit, and often only tenuous. Indeed, translation of strategic guidance in terms of priority for strategic risks, geographic focus and general tasks for the ADF into capability is the main historic weakness of Australian defence planning—going back at least to the 1970s ‘core force’ concept.

A key exception was the 1986 Dibb Review and 1987 Defence White Paper, which provided an (implicit) force structuring scenario for the defence of Australia, and explicit guidance on how the ADF would operate the ‘defence in depth’ strategy. In this framework lies the real importance of these documents, as it was internalised by Defence and government and implicitly guided defence force design until the 2000 white paper. No similarly impactful and enduring framework has replaced it.

The DSR’s reference to past planning against ‘low level and enhanced low-level threats’ (para 4.7) shows that it was conscious of this history, and seeks to provide a new framework that can have similarly lasting impact. In that sense, the most important paragraph of the DSU is that ‘the ADF needs a much more focused force structure based on net assessment, a strategy of denial, the risks inherent in the different levels of conflict, and realistic scenarios agreed to by the Government.’ What does this mean?

The use of politically, operationally and technically realistic scenarios that align with government strategic intent is key to coherent force design. Internationally, explicit political endorsement of force design scenarios are key elements of defence planning as in the United States; or the NATO defence planning process. Not so in Australia, where historically capability scenarios have only been endorsed by the Chiefs of Staff Committee. Even in white papers, ‘force structure reviews’ often preceded decisions that the government wanted Defence to achieve in the first place. Political endorsement of ADF force structuring scenarios will be crucial for government’s ability to ensure that the process which produces the capability proposals it receives from Defence actually reflects its strategic priorities.

The review’s reference to a ‘net-assessment planning process’ and rejection of a ‘balanced force’ (para 8.3) , which it understands to be designed to be able to react to a ‘range of contingencies’, provide a crucial insight into what the review wants these scenarios to entail. Net assessment as an analytical method has many applications, but the context makes clear that the review wants the ADF to be designed to meet one, extant, actual, clear and present threat (from China) rather than a range of possible or notional adversaries. Also sometimes called ‘threat-based planning’, ADF force design should in future reflect much more closely the actual shape and challenges that a conflict with China would present. As was the case for the US and NATO during the Cold War, changes in Chinese force structure and capabilities will flow much more directly and urgently into Australian capability priorities. The review’s recommendation that government direct a ‘strategy of denial’ is a consistent and necessary element of this approach, insofar as it explains how government would want the ADF to meet this threat.

As Australia is likely to operate alongside the US in such a conflict, and China’s ability to project force against Australia would depend on US action elsewhere, the review likely has set Australia onto a path towards much closer cooperation with the US in force design than has been the case since the SEATO alliance. The review’s comments about ‘recent advances’ in the bilateral and trilateral relations between the US, Japan and Australia hint at this, insofar as the review of alliance ‘roles’, ‘missions’ and ‘capabilities’ and the ‘scope’, ‘objectives’ and ‘forms’ of cooperation are part of these. NATO has always had a process for force structuring at the alliance level, and we may now be on our way to a more informal version of one.

The final element is the explicit consideration of ‘levels of conflict’ (para 7.8). Since the late 1960s, the starting point of Australian defence planning guidance has been geography, as priorities and objectives were framed through geographic regions (Australia, Southwest Pacific, Southeast Asia, Northeast Asia, and the global level), variations of which dominated the table of contents of every strategic review and white paper since 1968. In contrast, the DSR takes us back to the 1950s and 1960s when Australian defence policy was last dominated by the threat of great power conflict. Then, too, defence planning was framed in terms of what level of conflict Australia should focus on—in particular, Cold War (today: competition), limited war, and global (today: major) war. These remain meaningful distinctions today and lead to very different geographic as well as force structure and posture foci.

In competition, the ADF needs to be able to best respond to the security concerns of those countries over whose alignment we are competing by reflecting the interests in economic, resource and domestic security of South West Pacific and Southeast Asian countries. Today’s lightly armed and lightly built offshore patrol vessels are an example of a capability almost only useful for competition.

In limited conflict, by definition both sides accept that limited stakes impose limits to escalation and acceptable cost of conflict. Territorial conflict over maritime features other than Taiwan, or confrontations over incidents at sea, may today reflect such circumstances. Australia and partners would seek to manage limited conflict by deterrence through forward presence of highly capable, visible surface and air forces—including in regions such as the South China Sea where they would not be survivable in major war. Kinetic use of submarines against surface vessels would likely be subject to direct political concern about escalation, as was the case of the Belgrano sinking in the Falklands war. The main axis of ADF operations would be north-south, from Australia to the likely areas of conflict.

In major war, both sides fight to disarm and thus impose their will on the adversary. War termination will come to rest on the nuclear balance (if only in the sense that one side accepts cutting its losses rather than risk escalation). Australia’s main concern will be to secure supplies to remain in the fight, to avoid catastrophic losses, and to influence the shape of a post-war settlement in our immediate approaches. The main axis of ADF operations would thus be east-west, reflecting the crucial sea lines of communication to bring supplies across the Indian and Pacific Oceans, with US long-range strike forces operating north from the continent.

The guidance in the 2020 defence strategic update was arguably compatible with preparations for any three of these levels of conflict. While the review in its unclassified form is silent on what it would recommend government focus on, its insistence that the ADF is ‘not fit for purpose’ (para 8.2), emphasis on long-range strike, hardening of bases and fuel reserves in Australia hints at a classified recommendation to focus on major war.

The review and government have clearly internalised the need for much faster, and more robust and coherent adaptation than Defence has been able to provide. The effective admission that the post-2016 contestability agenda has failed (paras 12.2-3) shows the difficulty of reforming Defence, despite the clear efforts of Defence leadership and governments of recent years. Time will tell how long the intended biannual cycle for the new national defence strategy will survive a three-yearly electoral cycle, but it would in any case only be an outcome of the underlying defence planning framework. Hence, the review’s section on defence planning and force design is arguably not just the most brief, but also the most important, and—if implemented—would well warrant the minister’s moniker as the ‘most ambitious review’ of them all.

Ten years ago, retired Air Vice-Marshal John Blackburn released a landmark study that revealed the fragile state of Australia’s liquid-fuel security. It highlighted the country’s sole reliance on oil-based fuels for national transport systems and described its limited and declining sovereign refining capability. It also noted that Australia, the world’s ninth largest energy producer, is reliant on imports of crude and refined petroleum products. Fuel remains critical to the nation’s military capability, as the 2020 defence strategic update recognised when it identified the requirement to expand the fuel-storage capacity at Australian Defence Force bases and facilities.

Australia has built up economic wealth and prosperity on the coat-tails of globalisation. As a nation, we have leveraged our rich natural treasures to build our economy through lucrative trade relationships with countries in the Asia–Pacific and throughout the world. If we can buy it cheaper overseas, we will. Pushed by market forces, most domestic refineries have been shut down and imports from Singapore and other countries make up 90% of our consumption—to the point where our just-in-time stocks are now on tankers making their way to Australia. Indeed, fuel security may well become Australia’s Achilles’ heel.

Based on current domestic demand and usage rates, Australia has enough fuel to last approximately 68 days, though it is less for some individual fuels. In the event of a supply shock—whether through a disruptive weather event, political unrest or a direct military threat—consumption rates could increase dramatically. According to a recent parliamentary inquiry, shipping lane disruptions are seen as a tactical response challenge to be met by alternative sourcing, rather than an issue of defence capability degradation.

Observations from the war in Ukraine have certainly highlighted the fragility of the global fuel supply chain. A conflict in the Asia–Pacific would have devastating impacts on Australia’s fuel supplies and directly affect our domestic and military capabilities.

The scale of this issue requires a paradigmatic shift in thinking about fuel supply-chain management, government spending and the security of the nation.

So, then, how much is enough? It’s difficult to tell, and there is no definitive answer to how much fuel we need to sustain domestic industry concurrently with intensified military operations. The Fuel Security Act 2021 incorporates a number of initiatives, including boosting Australia’s diesel storage, upgrading refineries, and encouraging the development of sustainable aviation fuels and biofuels. These are positive steps, but they amount to band-aid solutions to a systemic vulnerability.

The bottom line is that Australia needs to invest more in fuel security. The US recently started construction of a 300-million-litre aviation fuel storage facility for the US Air Force in Darwin valued at $270 million. Ownership is nine-tenths of the law, and I expect Australia will play second fiddle for fuel supply from these new facilities.

More sovereign Australian investment will require robust and honest supply-chain modelling to determine an acceptable level of strategic risk mitigation. In an economic climate still recovering from Covid-19, fires and floods, the pressures on the federal budget are many. For the ADF and Defence Department, increasing strategic tensions, domestic response requirements, personnel retention challenges, and ever-expanding capability scope lead to a dynamic and challenging operating environment. Any call to spend more comes with inherent trade-offs.

We myopically compromise capability when platform acquisition isn’t balanced with fuel-security measures. For example, Exercise Pitch Black is the most significant multinational large-force employment exercise hosted by Australia. It involves defence force elements from up to 16 nations, performing hundreds of missions. It ‘features a range of realistic, simulated threats which can be found in a modern battle-space environment and is an opportunity to test and improve our force integration’, and yet reported fuel-supply issues and shortages hamstring the rehearsal of significant defence capabilities throughout the exercise.

Inadequate fuel security has a direct impact on the employment and effectiveness of our defence capabilities. Prudent fuel security helps to optimise the effectiveness of our modest arsenal of defence capabilities so that they don’t end up as expensive museum pieces. This is true of all current, developing and future capabilities.

My proposed radical paradigm shift is to take a portion of every budgeted defence capital expenditure item, such as capability development and acquisition projects, and allocate those resources to national and defence-related fuel-security projects. The portion set aside will, no doubt, be the subject of much political debate and scrutiny. For the purposes of this argument, however, I propose an arbitrary 10% allocation. If we consider the $16.76 billion in capital expenditure apportioned to defence for departmental programs in the 2022–23 budget, this would result in a fuel-security allocation of $1.68 billion. Investment should be made in projects that further Australian fuel security, including the expansion and deepening of current initiatives.

Balancing the desired effects of defence capabilities with a further restricted project budget will require some lateral thinking, moving from an all-exquisite-capability mindset to more innovative and out-of-the-box thinking. This self-reliant-by-design model will not only drive large, wide-scale investment in fuel-security solutions, but will also spur innovation and creative thinking within defence capability projects.

To simply state that Australia needs more fuel security may seem flippant, but it’s a function of the wicked problem our nation is facing. The current policies and initiatives offer a step in the right direction, but a radical paradigm shift is needed to build fuel security, almost from scratch. Whatever future challenges Australia may encounter, securing a dependable and self-reliant fuel supply chain is worthy of our attention and investment for the prosperity and welfare of current and future generations.

We must act now to avoid turning fiction into reality; to quote from Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior, ‘Without fuel they were nothing. They’d built a house of straw.’

There are good reasons why the best science and speculative fiction ranks high on the reading lists of many military scholars and leaders. Done well, speculative military fiction projects thoughtfully beyond the here and now, and renders real operational and strategic concepts in terms of plausible future technologies. This encourages us to think outside the box about our doctrine and our operational assumptions.

The Strategist is publishing two pieces by Jeffrey Becker, leading futurist for the US military, as prime examples of this kind of fiction. Today’s piece, ‘Aces-high frontier’, was first published in January 2019 in The Strategy Bridge. We are republishing it today with kind permission because many of its speculations have been vindicated by real events in Ukraine and elsewhere, showing the foresight that such fiction can achieve. Set in 2053, it discusses ideas such as a ‘kill mesh’, anticipating the lessons learned by Russian forces about combined arms and the role of the private sector, with even a nod to Elon Musk, to give just a couple of examples.

The second piece, to be published in coming months, is new. It examines the importance of rocket forces, advanced space capabilities and, most importantly, adaptation and innovation of people to win the fight on earth. When we look back at these piece of fiction in a few years’ time, how much will be reality, or on its way to becoming reality?

Kill mesh

You expect an electric crackle, the deep whine of machinery, a bolt of red across a planetary foreground, the roar of rocket engines. Wrong. When the US Space Force is in action, it really couldn’t be less cinematic. Anti-visual even.

Yes, the earth is still an astonishing sight from our perch at the earth–moon L4 Lagrange point, but battle itself is rather anticlimactic. No explosions. No starfighters careening this way and that.

The fight I manage (and ‘manage’ in this case is a term I use loosely) unfolds at inhuman speeds. Warfare in 2053 stretches over most of the planet. Thrusts, counters, feints all flash by in the millions over milliseconds. Remorseless AIs manoeuvre electrons, photons, code and data to blind, spoof, confuse, glitch and burn up microchips, radars and anything tied to a computer chip, radar or sensor.

Someone plastered a bright red sticker with an arrow labelled ‘Pointy End’ next to the heads-up display as a joke. How can anything in a 10,000-ton tin can 24,000 miles up be at the pointy end of anything?

But what happens here is very much the cutting blade of US military power worldwide.

‘Admiral Lane,’ ACES called out from my display. ‘Bithammer engagement appears to be successful.’

ACES is the call sign of the L4 station’s global integration AI. The joint force has several joint AIs in action around the world; ACES is at the core of L4 station’s mission and the real secret sauce for US Space Force operations up here.

The main job of the L4 station is to protect and feed ACES as it sifts through the trillions of bits collected from sensors, radar returns, emitters and data brought back from cyber-scout AIs. Few movements of military equipment happen planetside without L4 observing and understanding. ACES constantly assesses the military environment and manoeuvres space force assets and tens of thousands of robotic and human land, space and air enablers into place.

ACES can also direct an array of laser, electronic-warfare and cyber-assault capabilities from orbit. Most can reach targets from the earth’s surface to geosynchronous orbit. Primarily consisting of Constellation-class and Viper-class satellites, ACES works to cover and protect every joint force movement, munition, base and facility with electromagnetic and cyber fire. In this kill mesh, machine-age weapons like tanks, surface ships and fighter aircraft are not useful on their own.

Although space force operations are not very visually spectacular, the results of engaging from space are really quite effective.

Satisfying.

Usually, radars burn up, platforms go dumb, 3-D printers trying to construct or rebuild bricked components make defective replacements. Things just don’t work as the space force amplifies and weaponises Clausewitz’s fog and friction.

ACES collects full-motion, real-time hyperspectral data at one-inch resolution from thousands of orbiting platforms. Space force radars and lasers seek out sensors and emitters, while ACES catalogues and probes interesting targets with mobile code. ACES collects this information and builds a synthetic model of the world to understand meaning and implications.

‘Request authority to execute interdiction mode 4,’ ACES asked through my immersive display.

‘Granted.’ This command provides the AI with the parameters to coordinate global cyber, electromagnetic and directed-energy strikes against groups of the People Liberation Army’s air, maritime and ground mobile orbital interdiction lasers.

These mobile lasers are enforcing a self-declared orbital defence identification zone, or ODIZ, stretching from 60 miles up to geostationary orbit. China currently demands that satellite operators pay a fee to transit over its territory and comply with restrictions on sensing or emitting while inside the ODIZ.

‘Employing 263 femtosecond laser pulses, from six Viper platforms.’

Each of these pulses would send a cascade of gamma radiation through its target. Although the primary effect is to damage the adaptive optics actuators, ACES is manoeuvring viruses through the temporarily blinded firewall, allowing mobile lock code to infiltrate the system and beaconing the system for follow-on targeting.

‘Continuing engagements.’

ACES scanned the surface for other systems attempting to enforce the ODIZ. ACES sums up thousands of scans, cyber reconnaissance actions, and the results of correlation analysis on my screen. Streaks of green began to appear within the red orbital zone above China denoting corridors clear of the laser and electronic-warfare threat from the ground.

Decades of deep neural net correlation analysis and millions of simulations mean we trust that ACES can confound, disrupt and destroy when we need it to. And we need it to. The president ordered ACES into action to maintain orbital freedom of navigation over China despite the ODIZ.

Operating from US Space Force Base L4

Why build a military facility at L4?

The oldest rule in the book is to fight from the high ground. And from L4 everything is effectively downhill. Better yet, objects put here tend to stay here. It’s also why private companies gently and carefully moved a pair of half-mile-long asteroids to this specific spot in orbit in the late 2030s.

The asteroids, Plymouth and Williamsburg, are brightly visible from the station’s observation deck. Plymouth is a chunk of raw metal and home to many lucrative mining and manufacturing facilities. The ice of Williamsburg is even more valuable, supporting a thriving satellite refuelling business, shuttling hydrogen and oxygen to users far more cheaply than bringing it up from earth.

Right now, only Five Eyes partner nations mine here. Many other nations don’t believe we should be able to capture and use these for exclusive commercial purposes. Part of the L4 mission is to keep an eye on these commercial activities, as US national strategy directs the space force to protect scientific and economic access to outer space for the US and its allies and partners around the world.

Suddenly, my visual display froze and the station shuddered hard, visibly accelerating towards Plymouth. Much closer than I would like.

ACES came up on the headset again. ‘Sir, several temperature spikes are reading across the station. External communications shut down, and pointing and tracking temporarily disrupted.’

‘What’s the cause?’

‘I assess that we’ve been struck by several bursts of a high-energy laser. The targets suggest that the attack is intended to interdict our counter-ODIZ campaign. In fact, I’ve lost control over the Vipers currently operating in the China–LEO theater. Working to restore.’

The lights throughout the station flashed momentarily. Air vents not blowing. Not good.

‘ACES, where is it coming from? I thought you had the draw on any DE in range of the station?’

‘The geometry of the attack and the energy flux indicate a laser with a capacity of a petawatt or greater striking from the southern polar region of the lunar surface.’

How we fight

The US Space Force was really a response to the Chinese, who since the 2020s had increasingly knitted space, cyber and electronic-warfare capabilities in its innocuously named Strategic Support Force. China recognised the need to be vigilant, active and dominant in information confrontation in all its forms.

Indeed, as far back as 2005, Chinese writers noted that ‘before the troops and horses move, the satellites are already moving’. They understood very early that without space dominance, information dominance would not be possible. Without information dominance, operations in the air, sea and land would fail. Thus, in the Chinese mind, space would inevitably be a battleground.

The Chinese and the Russians appeared to be well in advance of us on the conceptual importance of the fusion of information, space, cyber and the electromagnetic spectrum. What set the US Space Force in a class by itself was its inexplicable—almost magical—lead in space lift.

‘Thank you, Elon Musk,’ I thought, picturing Musk’s cherry-red first-run Tesla at the entrance to his compound on Mars.

EBFR rockets and space vehicles (SpaceX for ‘Even Bigger Falcon Rocket’) allowed the US and its partners and allies to build a thriving commercial space industry. Like the historic Model T, DC-3 or Nimitz-class carrier, EBFR is a tangible and easily recognised symbol of American technology and power.

The Chinese still don’t have anything as big, cheap and capable as EBFR. The Russians are still dumping their used rockets at sea.

We use dozens of EBFRs to throw thousands of mass-produced satellites in orbit almost at will. Our global command-and-control network funnels data to the L4 station and knits it together into a real-time, multispectral Google Earth. ACES thinks through this tsunami of data, simulates and emulates it, and provides near-real-time, in-depth analysis of activities and probabilities of all military infrastructure on the planet. We can even rewind.

The big dark

Because of our overwhelming competitive advantages in space, the Chinese went a different way—focusing instead on lasers, hypersonics and quantum-based encryption, and hiding their goals and objectives.

We didn’t see this direct attack on L4 coming. We didn’t see the ODIZ declaration coming.

‘ACES, what do you know about the Big Dark?’

‘Although we can still see what’s going on physically within China and around the world, I calculate they’ve been able to pull together quantum computers, communications and optical elements into an end-to-end secure network. Although I can sometimes detect the links between different nodes, when I attempt to decrypt the messages, they disappear.’

‘Meaning?’

‘I suspect they’ve used my ignorance to plan and execute this ODIZ enforcement effort. Pushing their airspace and keeping us behind Plymouth means I can’t observe China from space. That unlocks their ballistic and hypersonic systems as well as air, sea and land assets to operate without interference.’

I thought for a moment. ‘We’re blind and our forces on earth are vulnerable to attack.’

Operation AlphaGo

‘Sir, the shuddering you felt was me moving the station behind Plymouth. This puts the asteroid between us and the moon. The L4 station is very well protected here. No laser can penetrate a rock of this size. However, we are pinned down and I cannot integrate counter-ODIZ operations. I anticipate large-scale terrestrial movement of their forces soon.’

‘What is going on with China on the moon? I mean, beyond the fact that they’ve managed to install a working battle laser without us noticing.’

The 10-person research station at the moon’s south pole has always been something of an enigma. Strangely, over the past decade they worked to string kilometres of wire in a radio-astronomical instrument conveniently spanning the moon’s only accessible sources of water.

The Chinese recognise how touchy we are about incursions on our old Apollo sites. Like us, they refer to the instrument as the common heritage of mankind that should not be disturbed. This put most of the moon’s water under their direct control. It also means they have the fuel to power a station capable of operating a laser of that size.

ACES thought for an interminable moment. (I find long pauses from AI very disturbing.)

‘AlphaGo versus Sedol, game 2, move 37,’ came back over my headset.

Sometimes ACES free-associates things. Humans often take time to catch up with the mental connections AIs can make. However, the reference to Lee Sedol’s epic 2016 Go match with AlphaGo was clear. The Aerospace War College’s ‘Intro to AI’ class (taught by an AI, of course) uses the game as an example of how AI can demonstrate extraordinary, superhuman foresight.

Go was thought to be too complex for AIs to compete with world-class human players. AlphaGo placed a black stone in a position never seen in Go’s 2,000-year history. Sedol left the table in shock at the long-term implications of the move and soon resigned the game.

‘So, while we’ve been focused on earth, China managed to put a working weapon on our spaceward flank?’ I asked.

‘Yes.’ ACES replied. ‘My working hypothesis is that the base has built a laser capable of interdicting us in GEO and L4. Maybe even to earth itself. In effect, this laser is a black-piece move so far off the board that it appears irrelevant, but is really a potentially dominant strategic gambit.’

‘The Chinese are playing a game of position against our campaign of manoeuvre and cyber-electromagnetic attrition?’

‘Yes,’ ACES replied. ‘I’ll need some assistance setting new parameters, Admiral.’

ACES fit together a number of movements into a potential Chinese theory of victory. The most likely scenario playing out on my strategic display—now showing the broader earth–moon system, key orbits and positions, as well as how a struggle for control might unfold. A bright red point radiated out from the moon’s south pole, rays beginning to isolate the L4 station and collapsing our ability to use orbital space and thus to control the information confrontation on earth.

ACES began to put together options, already communicating designs for a fast-moving weapon to attack the moon station. The vehicle, built out of an entirely new ring and stack assembly, would be shaped and moulded from Plymouth’s metal. Looking like an alien spider web of tangled metal, the assembly would distribute high-G loads from three connected EBFR orbital segments and a formation of observation, Viper and Constellation sats. The spider web would allow the EBFRs to deliver a fleet of combat sats towards the lunar base at high speed.

But first, the spider web would be connected to a rough slab of ice cut from Williamsburg. The ice slab would shield the satellites and EBFRs from the attacking lunar laser. After departing earth orbit, the jury-rigged vehicle would swing 35 miles above the lunar south pole. At perigee, three observation sats would detach from the spider web, emerging from behind the slab in different directions and mapping the Chinese lunar base below. They would be destroyed quickly, but ACES could use the data to construct a model of the base, ejecting and manoeuvring nine Viper and Constellation sats from behind the slab seconds later, hitting as much of the base’s critical infrastructure as possible.

Two days later, after swinging through a high, looping orbit, the remainder of the stack, including the spider web and ice shield, would crash into the base, making an immense crater and putting the laser (and probably the whole station) out of business for good.

The president flashed up on the display. ‘Admiral Lane. I understand you are under attack. What do you advise?’

‘ACES, will you please show the president the concept?’

The debate on how best to defend Australia in a worsening strategic environment is likely to be substantially settled with the defence strategic review, due for completion in March. Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Richard Marles recently emphasised the need for long-range strike capabilities, including by referring to ‘impactful projection’. He reinforced the requirement for Australia to project military effect at long range, saying: ‘We must invest in targeted capabilities that enable us to hold potential adversaries’ forces at risk at a distance and increase the calculated cost of aggression against Australia.’

Marles is being very clear that long-range strike and, by extension, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) are priorities that will be reflected in the strategic review. That ISR capability has to have a targeting component based on multi-domain capabilities, notably including space-based sensors.

Simply put, we need to see far to strike far. The sensor ends of that ‘kill chain’ must be resilient, even in highly contested environments, and have a sustained hemispheric gaze from Australia’s shores. Crewed aircraft such as the P-8A Poseidon or autonomous aerial vehicles such as the MQ-4B Triton are but one part of any future ISR capability for the Australian Defence Force.

The increasing ability of a major-power adversary such as China to project military force, along with uncertainty over our access to forward basing, raises the risks in sustaining these aircraft on station, distant from Australia’s air and maritime approaches. The small number of aircraft Australia operates reinforces these challenges—only six MQ-4B Tritons will be available, for example. Certainly, submarines can also play a role in tactical intelligence gathering, as can surface combatants, but we only have six ageing Collins-class diesel–electric boats, and the nuclear-powered submarines being acquired under AUKUS won’t appear until the late 2030s at best. Naval surface combatants are becoming more vulnerable inside an adversary anti-access/area-denial envelope characterised by ever more sophisticated long-range missiles and long-range surveillance systems.

Reliance on close-in surveillance that only allows us to respond to a threat within Australia’s air and maritime approaches is not sufficient. That surrenders the initiative to the adversary, which could then strike our key northern infrastructure from outside the reach of coastal defences and short-range tactical fighters. We’re recognising that our ‘strategic moat’, traditionally perceived as the sea–air gap to our north, is not so defensible in these days of precision conventional ballistic missiles, hypersonic cruise missiles, and cyber and counter-space capabilities. China has all these already and is continuing to expand and develop them.

Chinese ships can target northern Australia from within the Indonesian archipelago, and Australia is in range of Chinese land-based missiles and long-range bombers in the South China Sea. So, our gaze must penetrate far and deep across the Indo-Pacific region. Space-based ISR that is pervasive and resilient, even in the face of adversary counter-space threats, seems to be the best answer.

Last year on this forum, Daniel Molesworth highlighted the importance of building a dedicated surveillance and target acquisition capability for the Australian Army’s long-range fires, based on tactical uncrewed aerial systems. He suggested that the Defence Department re-establish Project Air 7003 to acquire remotely piloted drones such as the MQ-9B Sky Guardian. That’s a good idea, particularly in relation to the employment of shorter-range guided missiles on the US-made High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS) that Australia will be acquiring.

However, space-based capabilities take us the next step to hemispheric surveillance and targeting for very long-range strike. Those capabilities will be essential if Australia acquires much longer-range power projection, such as that implicit in platforms like the B-21 Raider or an evolved version of the MQ-28 Ghost Bat. The nuclear submarines will also require targeting for both land-attack and anti-ship operations.

Defence is already supporting key space projects, such as the recently announced National Space Mission for Earth Observation, a civilian-oriented project led by the Australian Space Agency, CSIRO and Geoscience Australia. The satellite capability it provides will have some utility in tasks such as bushfire response, disaster relief and maritime domain awareness, but it’s not a dedicated defence capability.

Defence needs to acquire its own satellite constellation in low-earth orbit that can provide high-resolution imagery for target detection and precision tracking to support long-range strikes. Such a constellation could complement larger geospatial intelligence-gathering capabilities, such as those to be operated by the Australian Geospatial-Intelligence Organisation under Defence Project 799 Phase 2.

Last year, Australia supported two launches for the US National Reconnaissance Office, in cooperation with the Defence Department, under the ‘Antipodean Adventure’ program. Although they are US satellites, Australian involvement gives Defence valuable experience ahead of acquiring sovereign space surveillance capabilities. Also last year, Gilmour Space Technologies announced a partnership with LatConnect 60 to launch eight satellites on Gilmour’s Eris launcher from 2024 to provide commercial earth observation, including for defence applications.