Having announced its intention to publish a new Defence White Paper in the first half of 2013, the government has now taken the curious step of issuing a new Defence Capability Plan (DCP). That is, a new schedule for the approval of defence acquisition projects over the next four years. What’s curious is that a new DCP is normally the outcome of a Defence White Paper, rather than a precursor.

What’s more, given the short time since the substantial cuts to the defence spending in the May budget, the new DCP is at best a quick and dirty shoehorning of existing projects into the much-reduced funding envelope that’s available over the next four years. Moreover, how can the government be developing a new Defence White Paper but already know what capabilities it wants to pursue over pretty much the entire life of the document?

Logically, there are three possibilities; either the new DCP is worthless, the next White Paper is pointless, or both. Let’s hope that it’s the first of those options. The worst outcome would be a White Paper that ex facto justified the hastily cobbled together DCP.

In the meantime we have a new DCP to pore over. I’ll leave it to others to divine the implied shifts in strategy which the projects that have been included and excluded might imply—I’m not sure that strategy has much to do with Australia’s capability planning at the best of times. Instead, here’s my statistical analysis of the planned throughput of projects.

Under the two-pass process introduced back in 2003, defence projects are considered (at least) twice by the government; so-called ‘first pass’ and ‘second pass’ approval. At first pass the priority for the capability is confirmed, along with the range of options to be considered; at second pass an option is selected and given final approval. In the latest DCP, 25 of 111 projects are listed as having a combined or simultaneous first and second pass approval.

Because the DCP provides only multi-year bands for when project approvals are scheduled, it’s necessary to analyse the schedule using a statistical approach. Fortunately, with so many projects that gives a reasonable average result, so it’s possible to calculate the number of approvals required each year to deliver the plan.

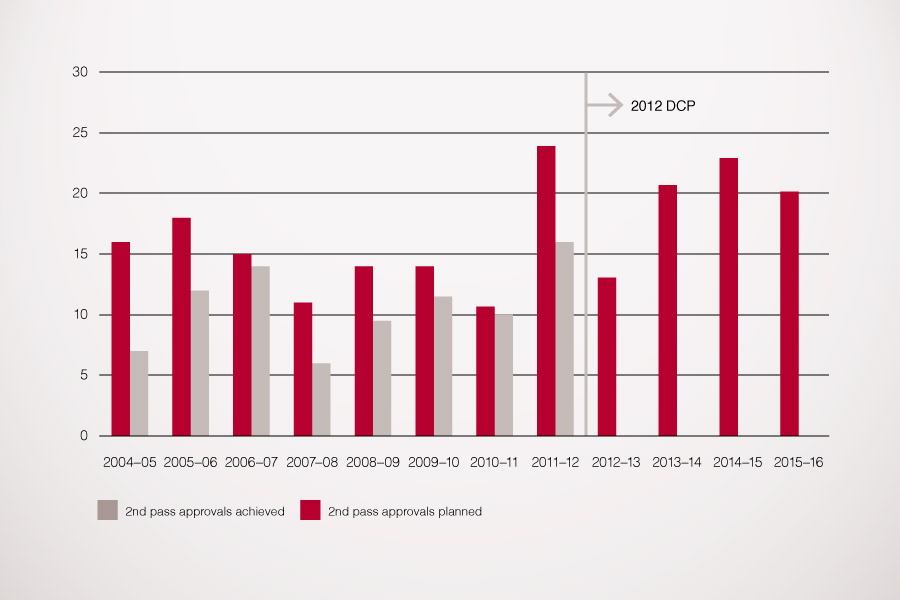

The graph below (click to enlarge) shows the average number of projects planned and achieved for second pass approval since 2004—that is, the number of projects that have been green-lighted to commence. Two things are apparent. First, there have been continuing delays to the program; the actual number of projects approved in previous years has consistently been below the number planned. This matters because it means that the defence force will have to wait longer than planned for the equipment it presumably needs, and often means that ageing equipment has to soldier on longer than planned. Second, the number of approvals planned between 2013 and 2015 substantially exceeds recently achieved rates of approval.

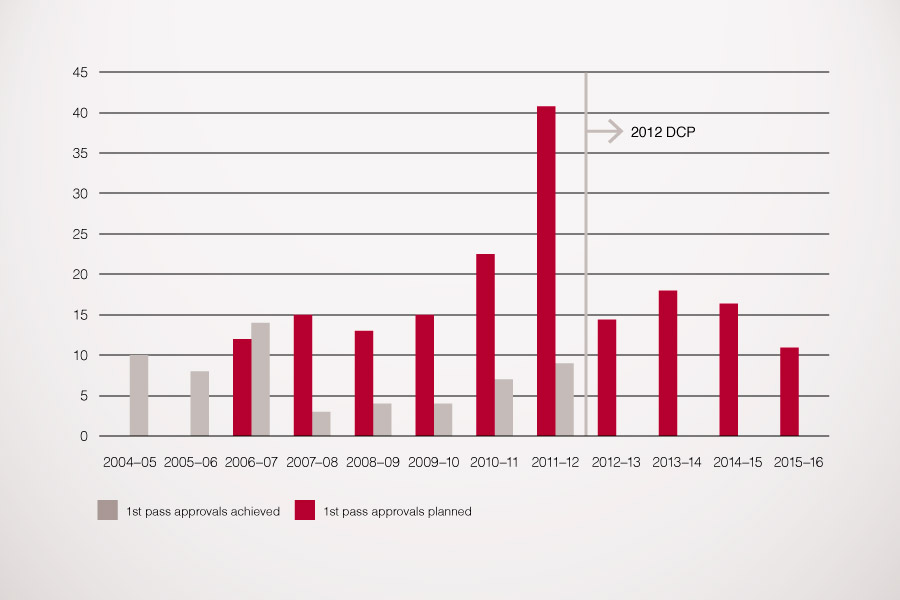

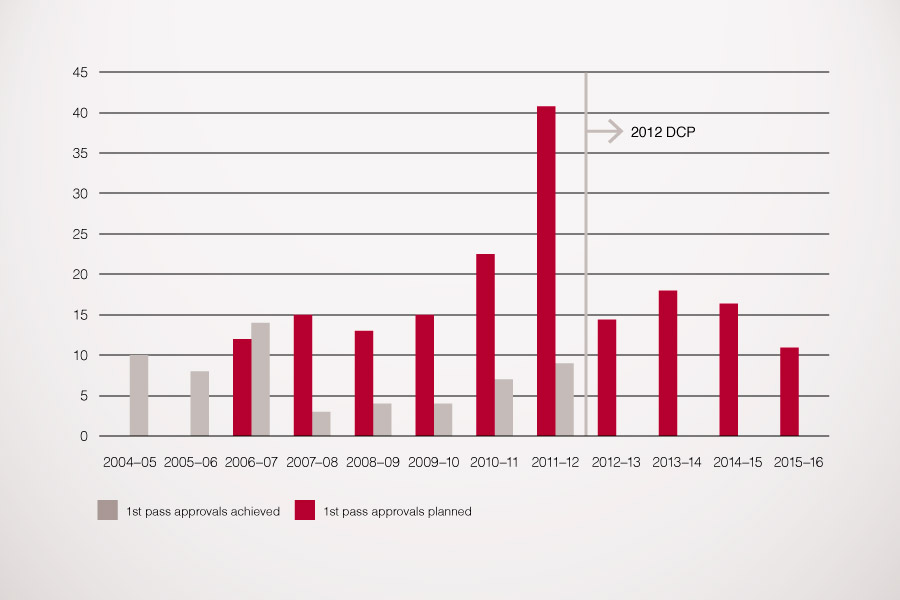

Let’s now look at how first pass approvals have been going. As shown below (click to enlarge), the picture is even less encouraging. On past experience, there is little chance of the envisaged rate of approvals being achieved. (There are no planned figures are available for 2004-05 and 2005-06 because the first-pass milestone was introduced after the 2004 DCP was published.)

However, in putting together the graphs above, combined approvals have been counted as both a first- and second-pass approval. It may be that there is less work required when a combined approval occurs, meaning that the task ahead is less difficult than it might first appear. But whatever solace we take from that point must be tempered by the knowledge that there is a White Paper due in 2012–13 and an election in 2013–14, and past experience shows that such events seriously delay the approval of projects.

However, in putting together the graphs above, combined approvals have been counted as both a first- and second-pass approval. It may be that there is less work required when a combined approval occurs, meaning that the task ahead is less difficult than it might first appear. But whatever solace we take from that point must be tempered by the knowledge that there is a White Paper due in 2012–13 and an election in 2013–14, and past experience shows that such events seriously delay the approval of projects.

So where does that leave us? It will be interesting to compare the first post-White Paper DCP with the one just released. Unless there are significant differences between the two documents, the White Paper will have been an irrelevant waste of time—akin to the cheap magician’s trick of telling you the number you first thought of. At the very least, let’s hope that the new schedule of project approvals is more realistically aligned with past experience than what’s just been released.

Mark Thomson is senior analyst for defence economics at ASPI.