A new Sino-Russian high-tech partnership

Authoritarian innovation in an era of great-power rivalry

What’s the problem?

Sino-Russian relations have been adapting to an era of great-power rivalry. This complex relationship, categorised as a ‘comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for a new era’, has continued to evolve as global strategic competition has intensified.1 China and Russia have not only expanded military cooperation but are also undertaking more extensive technological cooperation, including in fifth-generation telecommunications, artificial intelligence (AI), biotechnology and the digital economy.

When Russia and China commemorated the 70th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China in October 2019,2 the celebrations highlighted the history of this ‘friendship’ and a positive agenda for contemporary partnership that is pursuing bilateral security, ‘the spirit of innovation’, and ‘cooperation in all areas’.3

Such partnerships show that Beijing and Moscow recognise the potential synergies of joining forces in the development of these dual-use technologies, which possess clear military and commercial significance. This distinct deepening of China–Russia technological collaborations is also a response to increased pressures imposed by the US. Over the past couple of years, US policy has sought to limit Chinese and Russian engagements with the global technological ecosystem, including through sanctions and export controls. Under these geopolitical circumstances, the determination of Chinese and Russian leaders to develop indigenous replacements for foreign, particularly American technologies, from chips to operating systems, has provided further motivation for cooperation.

These advances in authoritarian innovation should provoke concerns for democracies for reasons of security, human rights, and overall competitiveness. Notably, the Chinese and Russian governments are also cooperating on techniques for improved censorship and surveillance and increasingly coordinating on approaches to governance that justify and promote their preferred approach of cyber sovereignty and internet management, to other countries and through international standards and other institutions. Today’s trends in technological collaboration and competition also possess strategic and ideological implications for great-power rivalry.

What’s the solution?

This paper is intended to start an initial mapping and exploration of the expanding cooperative ecosystem involving Moscow and Beijing.4 It will be important to track the trajectory and assess the implications of these Sino-Russian technological collaborations, given the risks and threats that could result from those advances. In a world of globalised innovation, the diffusion of even the most sensitive and strategic technologies, particularly those that are dual-use in nature and driven by commercial developments, will remain inherently challenging to constrain but essential to understand and anticipate.

- To avoid strategic surprise, it’s important to assess and anticipate these technological advancements by potential adversaries. Like-minded democracies that are concerned about the capabilities of these authoritarian regimes should monitor and evaluate the potential implications of these continuing developments.

- The US and Australia, along with allies and partners, should monitor and mitigate tech transfer and collaborative research activities that can involve intellectual property (IP) theft and extra-legal activities, including through expanding information-sharing mechanisms. This collaboration should include coordinating on export controls, screening of investments, and restrictions against collaboration with military-linked or otherwise problematic institutions in China and Russia.

- It’s critical to continue to deepen cooperation and coordination on policy responses to the challenges and opportunities that emerging technologies present. For instance, improvements in sharing data among allies and partners within and beyond the Five Eyes nations could be conducive to advancing the future development of AI in a manner that’s consistent with our ethics and values.

- Today, like-minded democracies must recognise the threats from advances in and the diffusion of technologies that can be used to empower autocratic regimes. For that reason, it will be vital to mount a more unified response to promulgate norms for the use of next-generation technologies, particularly AI and biotech.

Background: Cold War antecedents to contemporary military-technological cooperation

The history of Sino-Russian technological cooperation can be traced back to the early years of the Cold War. The large-scale assistance provided by the Soviet Union to China in the 1950s involved supplying equipment, technology and expertise for Chinese enterprises, including thousands of highly qualified Soviet specialists working across China.5 Sino-Russian scientific and technical cooperation, ranging from the education of Chinese students in the Soviet Union to joint research and the transfer of scientific information, contributed to China’s development of its own industrial, scientific and technical foundations. Initially, China’s defence industry benefited greatly from the availability of Soviet technology and armaments, which were later reverse-engineered and indigenised. The Sino-Soviet split that started in the late 1950s and lasted through the 1970s interrupted those efforts, which didn’t resume at scale until after the end of the Cold War.6

Russia’s arms sales to China have since recovered to high levels, and China remains fairly reliant upon certain Russian defense technologies. This is exemplified by China’s recent acquisition of the S-400 advanced air defence system,7 for which China’s Central Military Commission Equipment Development Department was sanctioned by the US.8 Traditionally, China has also looked to Russia for access to aero-engines.9 Today, China’s tech sector and defence industry have surpassed Russia in certain sectors and technologies. For instance, China has developed unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) that are far more advanced than those currently operational in Russia.10 Nonetheless, the Russian military has been unwilling to acquire Chinese UAVs, instead deciding to attempt to develop indigenous counterparts in mid-range and heavy unmanned combat models.11 Nonetheless, for Russia, nearto mid-term access to certain Chinese products, services and experience may become the very lifeline that Russia’s industry, government and military will require in order to wean themselves off high-tech imports12, although even that approach may be challenged by limited availability of Chinese components.13

Underscoring the apparent strength of this evolving relationship, China and Russia have recently elevated their military-to-military relationship. In September 2019, the Russian and Chinese defence ministers agreed to sign official documents to jointly pursue military and military–technical cooperation.14 According to the Russian Defence Minister, ‘the results of the [bilateral] meeting will serve the further development of a comprehensive strategic partnership between Russia and China.’15

Reportedly, Russia plans to aid China in developing a missile defense warning system, according to remarks by President Putin in October 2019.16 At the moment, only the United States and Russian Federation have fully operationalized such technology, and according to Moscow, sharing this technology with Beijing could ‘cardinally increase China’s defense capability’.17 For China, access to Russian lessons learned in new conflicts such as Syria may prove extremely valuable as Beijing digests key data and lessons.18 Of course, this technological cooperation has also extended into joint exercises, including joint air patrols and naval drills.19

A strategic partnership for technological advancement

The strategic partnership between China and Russia has increasingly concentrated on technology and innovation.20 Starting with the state visit of Xi Jinping to Moscow in May 2015, in particular, the Chinese and Russian governments have signed a series of new agreements that concentrate on expanding into new realms of cooperation, including the digital economy.21 In June 2016, China’s Ministry of Science and Technology and Russia’s Ministry of Economic Development signed the ‘Memorandum of Understanding on Launching Cooperation in the Domain of Innovation’.22 With the elevation of the China–Russia relationship as a ‘comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for a new era’, the notion of these nations as being linked in a ‘science and technology cooperation partnership for shared innovation’ (作共同创新的科技合作伙伴) has been elevated as one of the major pillars of this relationship.23

To some degree, this designation has been primarily rhetorical and symbolic, but it has also corresponded with progress and greater substance over time. The Chinese and Russian governments have launched a number of new forums and mechanisms that are intended to promote deeper collaboration, including fostering joint projects and partnerships among companies. Over time, the Sino-Russian partnership has become more and more institutionalised.24 This policy support for collaboration in innovation has manifested in active initiatives that are just starting to take shape.

This section outlines five areas where the Sino-Russian relationship is deepening, including in dialogues and exchanges, the development of industrial science and technology (S&T) parks, and the expansion of academic cooperation.

Dialogues and exchanges

Concurrently, a growing number of dialogues between Chinese and Russian governments and departments have attempted to promote exchanges and partnerships, and those engagements have also become particularly prominent since 2016. While the initiatives listed below remain relatively nascent, these new mechanisms constitute a network of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) cooperation that could continue to expand in the years to come and provide the two countries with new vehicles for engagement and information sharing across their respective scientific communities.

- Starting in 2016, the Russian–Chinese High-Tech Forum has been convened annually. During the 2017 forum, both sides worked on the creation of direct and open dialogue between tech investors of Russia and China, as well as on the expansion and diversification of cooperation in the field of innovations and high technologies.25 During the 2018 forum, proposed initiatives for expanded cooperation included the introduction of new information technologies. This forum wasn’t merely a symbolic indication of interest in cooperation but appeared to produce concrete results, including the signing of a number of bilateral agreements.26 In particular, the Novosibirsk State University of Architecture and Civil Engineering signed an agreement with Chinese partners on the development of technologies for construction and operation in cold conditions.27 The specific projects featured included China’s accession to the Russian project of a synchrotron accelerator.28

- Beginning in 2017, the Sino-Russian Innovation Dialogue has been convened annually by China’s Ministry of Science and Technology and Russia’s Ministry of Economic Development.29 In the first dialogue, in Beijing, more than 100 Chinese and Russian enterprises participated, from industries that included biomedicine, nanotechnology, new materials, robotics, drones and AI, showcasing their innovative technologies and concluding new agreements for cooperation. During the second dialogue, in Moscow, the Russian and Chinese governments determined the 2019–2024 China–Russia Innovation Cooperation Work Plan.30 Each country regards the plan as an opportunity for its own development, as it combines the advantages of China’s industry, capital and market with the resources, technology and talents of Russia.31 Contemporaneously, forums have been convened in parallel on ‘Investing in Innovations’ and have brought together prominent investors and entrepreneurs.32 When the third dialogue was convened in Shanghai in September 2019, the agenda included a competition in innovation and entrepreneurship, a forum on investment cooperation and a meeting for ‘matchmaking’ projects and investments.33 The 70th anniversary of diplomatic relations will also be commemorated with the Sino-Russian Innovation Cooperation Week.34

Science and technology parks

The establishment of a growing number of Sino-Russian S&T parks has been among the most tangible manifestations of growing cooperation. Moscow and Beijing believe that scientific and industrial parks can create a foundation and an infrastructure that’s critical to sustained bilateral cooperation. Since so many of these efforts remain relatively nascent, it’s too early to gauge their success—yet the growing number of such efforts reflects growing bilateral cooperation.

- As early as 2006, the Changchun Sino-Russian Science and Technology Park was established as a base for S&T cooperation and innovation. It was founded by the Jilin Provincial Government and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, in cooperation with the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Siberian Branch and the Novosibirsk state of the Russian Federation.35 The park has specialised in creating new opportunities for collaboration and for the transfer and commercialisation of research and technology.36 Over more than a decade, it has built an ‘innovation team’ composed of colleges and universities, scientific research institutions and private enterprises.37

- In June 2016, the plan for the China–Russia Innovation Park was inaugurated with support from the Shaanxi Provincial Government, the Russian Direct Investment Fund and the Sino-Russian Investment Fund. The park was completed in 2018, with information technology, biomedical and artificial intelligence enterprises invited to take part. According to the development plan, the park aims at research and development of new technologies and the integration of new tech with the social infrastructure of both countries.38

- Also in June 2016, the Sino-Russian Investment Fund and the Skolkovo Foundation signed an agreement to build a medical robot centre and to manufacture medical robots in China with support from experts at the Russian Academy of Sciences’ School of Design and Technology.39 The state-funded Skolkovo initiative, launched in 2010, is Russia’s leading technology innovation space. The foundation manages many high-tech projects that include deep machine learning and neural network techniques.40

- In June 2016, the China–Russia Silk Road Innovation Park was established in the Xixian New District of Xian.41 This initiative is framed as an opportunity to construct a modern industrial system as the main line of development, ‘striv[ing] to create an innovation and entrepreneurship centre with the highest degree of openness and the best development environment in the Silk Road Economic Belt’. This park welcomes entrepreneurs from China and Russia.

- In December 2017, S&T parks from China and Russia agreed to promote the construction of a Sino-Russian high-tech centre at Skolkovo, which aims to become Russia’s Silicon Valley.42 The Skolkovo Foundation, which manages the site, agreed to provide the land, while Tus-Holdings Co Ltd and the Russia–China Investment Fund will jointly finance the project. This high-tech centre is intended to serve as a platform to promote new start-ups, including by attracting promising Chinese companies.

- In October 2018, the Chinese city of Harbin also emerged as a major centre for Sino-Russian technological cooperation.43 This initiative is co-founded by GEMMA, which is an international economic cooperation organisation registered in Russia, and the Harbin Ministry of Science and Technology.44 At present, 19 companies are resident in the centre, which is expected to expand and receive robust support from the local government. Harbin’s Nangan District has expressed interest in cooperation with Russian research institutes in the field of AI.45

- The cities of Harbin and Shenzhen have been selected for a new ‘Two Countries, Four Cities’ program, which is intended to unite the potentials of Moscow, Yekaterinburg, Harbin and Shenzhen.46 As of 2019, there are plans for the opening of another Russian innovation centre in the city of Shenzhen—a high-tech park that will concentrate on information technology47—enabling resident companies to enter the China market with their own software and technologies, such as big data and automation systems for mining.48

Joint funds

China and Russia are also increasing investments into special funds for research on advanced technology development.

- The Russia–China Investment Fund for Regional Development signed on as an anchor investor in two new funds at Skolkovo Ventures to the tune of US$300 million in October 2018.49 This fund will also pour money into Skolkovo’s funds for emerging companies in information technology, which each currently have US$50 million in capital.50

- The Russia–China Science and Technology Fund was established as a partnership between Russia’s ‘Leader’ management company and Shenzhen Innovation Investment Group to invest as much as 100 million yuan (about US$14 million) into Russian companies looking to enter the China market.51

- The Chinese and Russian governments have been negotiating to establish the Sino-Russian Joint Innovation Investment Fund.52 In July 2019, the fund was officially established, with the Russian Direct Investment Fund and the China Investment Corporation financing the $1 billion project.53

Contests and competitions

Engagement between the Chinese and Russian S&T sectors has also been promoted through recent contests and competitions that have convened and displayed projects with the aim of facilitating cooperation.

- In September 2018, the first China–Russia Industry Innovation Competition was convened in Xixian New District.54 The competition focused on the theme of ‘Innovation Drives the Future’, highlighting big data, AI and high-end manufacturing.55 The projects that competed included a flying robot project from Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics and a brain-controlled rehabilitation robot based on virtual reality and functional electrical stimulation.

- In April 2019, the Roscongress Foundation together with VEB Innovations and the Skolkovo Foundation launched the second round of the EAST BOUND contest, which gives Russian start-ups an opportunity to tell foreign investors about their projects. This time, the contest will support AI developments.56 The finalists spoke at SPIEF–2019 (the St Petersburg International Economic Forum) and presented their projects to a high-profile jury consisting of major investors from the Asia–Pacific region.57

Expansion of academic cooperation

In July 2018, the Russian and Chinese academies of sciences signed a road-map agreement to work on six projects.58 The agreement joins together some of the largest academic and research institutions around the world and includes commitments to expand research collaboration and pursue personnel exchanges. The Chinese Academy of Sciences has more than 67,900 scientists engaged in research activities,59 while the Russian Academy of Sciences includes 550 scientific institutions and research centres across the country employing more than 55,000 scientists.60

These projects include a concentration on brain functions that will include elements of AI.61 The Russian side is motivated by the fact that China occupies a world-leading position in the field of neuroscience,62 including through the launch of the China Brain Project.63 The Russian Academy of Sciences delegation visited laboratories in Shanghai in August 2019 and commented on their counterpart academy’s achievements:

Brain research is a whole range of tasks, starting with genetics and ending with psychophysical functions. This includes the study of neurodegenerative diseases and the creation of artificial intelligence systems based on neuromorphic intelligence. Participation in this project is very important for Russia. China is investing a lot in this and has become a world leader in some areas …64

Priorities for partnership

Chinese–Russian technological cooperation extends across a range of industries, and the degree of engagement and productivity varies across industries and disciplines. As Sino-Russian relations enter this ‘new era’, sectors that have been highly prioritised include, but are not limited to, telecommunications; robotics and AI; biotechnology; new media; and the digital economy.

Next-generation telecommunications

The ongoing feud between the US and China over the Huawei mobile giant has contributed to unexpectedly rapid counterbalancing cooperation between Russia and China. In fact, President Vladimir Putin went on the record about this issue, calling the American pressure on the Chinese company the ‘first technological war of the coming digital age’.65 Encountering greater pressure globally, and this year in particular, Huawei has expanded its engagement with Russia, looking to leverage its STEM expertise through engaging with Russian academia. Since 2018, Huawei has opened centres first in Moscow, St Petersburg and Kazan and then in Novosibirsk and Nizhny Novgorod.66

Huawei also began monitoring the research capabilities of Russian universities, searching for potential joint projects, and in August 2019 the company signed a cooperation agreement on AI with Russia’s National Technology Initiative, which is a state-run program to promote high-tech development in the country.67 Based on a competition run by the Huawei Academy and Huawei Cloud, Russia’s best academic STEM institutions were selected.68 In May 2019, Huawei and the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences outlined areas and means of future cooperation.69

Underscoring its bullishness, China recently announced plans for a fourfold increase in its R&D staff in Russia going forward. In May 2019, the Huawei Innovation Research Program in Russia was launched, and Russian institutions have received 140 technological requests from Huawei in various areas of scientific cooperation.70 By the end of 2019, the company intends to hire 500 people, and within five years it will attract more than 1,000 new specialists.71 Huawei now has two local R&D centres in Moscow and St Petersburg, where 400 and 150 people work, respectively.72 By the end of the year, it plans to open three new R&D centres, and Russia will then be ranked among the top three Huawei R&D centres, after Europe and North America.73 The company plans to engage in close cooperation with Russian scientific communities, universities and other research centres.

At present, Russia doesn’t appear to share deep American concerns about security related to Huawei technology.74 Huawei has started actively expanding its 5G testing in the Russian Federation, partnering with Russia’s Vimplecom to test a 5G pilot area in downtown Moscow starting in August 2019.75 Commentators have stated that Russia, which isn’t considered a technological leader, has ‘the potential to get ahead globally’ now that it has Chinese high-tech enterprises as allies.76 During the summer of 2019 at SPIEF, Huawei continued to discuss with Skolkovo plans to develop 5G network technology at the innovation centre, and also to do research in AI and internet of things (IoT) projects.77

In fact, at that forum, Russia and China outlined a large-scale cooperation program in order to prepare a road map for future investment and cooperation on issues such as cybersecurity and the IoT.78 As US pressure on Huawei continues, there’s even a possibility that the Chinese company might abandon the Android operating system (OS) altogether and replace it with the Russian Avrora OS.79 If this transaction goes through, it would be the first time that a Russian OS has contributed to a significant global telecoms player.

Whether Huawei can become a trusted name in Russia’s tech sector and defence industries remains to be seen. There are also reasons to question whether Russia truly trusts the security of Huawei’s systems, but it may be forced to rely upon them, absent better options. As an illustration of potential complications, in August 2019, Russia’s MiG Corporation, which builds Russia’s fighter jets, was caught in a legal battle with one of its subcontractors over software and hardware equipment.80 The subcontractor in question, Bulat, has been one of Russia’s most active companies in riding the wave of the ‘import substitution’ drive in effect since Western sanctions were imposed on the Russian defence industry. However, in this case, Bulat didn’t offer Russian-made technology; rather, it used Huawei’s servers and processors.81 Although MiG did not say publicly why it didn’t pay Bulat, it appears that the aircraft corporation actually requested Chinese technology for its operations. 82

Big data, robotics and artificial intelligence

For China and Russia, AI has emerged as a new priority in technological cooperation. For instance, the countries are seeking to expand the sharing of big data through the Sino-Russian Big Data Headquarters Base Project,83 while another project has been launched to leverage AI technologies, particularly natural language processing, to facilitate cross-border commercial activities, intended for use by Chinese and Russian businesses.84 China’s Ambassador to Russia, Li Hui, said at an investment forum in the autumn of 2018 that the two countries should increase the quality of bilateral cooperation and emphasise the digital economy as a new growth engine, highlighting opportunities for collaboration in AI, along with big data, the internet and smart cities.85 Ambassador Li emphasised:

Russia has unique strength in technological innovation and has achieved significant innovations in many fields of science and technology. China and Russia have unique economic potential and have rich experience in cooperation in many fields. Strengthening collaboration, promoting mutual investment, actively implementing promising innovation projects, expanding direct links between the scientific, business and financial communities of the two countries is particularly important today.86

This bilateral AI development will benefit from each country’s engineers and entrepreneurs.87 From Russia’s perspective, the combined capabilities of China and Russia could contribute to advancing AI, given the high-tech capabilities of Russia’s R&D sector.88 While Russia’s share of the global AI market is small, that market is growing and maturing.89 In Russia, a number of STEM and political figures have spoken favourably about the potential of bilateral R&D in AI. At the World Robotics Forum in August 2017, Vitaly Nedelskiy, the president of the Russian Robotics Association, delivered a keynote speech in which he emphasised that ‘Russian scientists and Chinese robot companies can join hands and make more breakthroughs in this field of robotics and artificial intelligence. Russia is very willing to cooperate with China in the field of robotics.’90 According to Song Kui, the president of the Contemporary China– Russia Regional Economy Research Institute in northeast China’s Heilongjiang Province, ‘High-tech cooperation including AI will be the next highlight of China–Russia cooperation.’91

In fact, bilateral cooperation in robotics development has some Russian developers and experts cautiously optimistic. According to the chief designer at Android Technologies, the Russian firm behind the FEDOR (Skybot F-850) robot that was launched to the International Space Station on 22 August 2019, ‘medicine may be the most promising for cooperation with China in the field of robotics.’92

However, hinting at potential copyright issues with respect to China, he further clarified:

[M]edical robotics is better protected from some kind of copying, because if we [Russians] implement some components or mechatronic systems here [in China], then we can sell no more than a few pieces … But since medical robotics is protected by technology, protected by the software itself, which is the key, the very methods of working with patients, on the basis of this, this area is more secure and most promising for [Russian] interaction with the Chinese.93

Revealingly, concerns about copying are a constraint but might not impede joint initiatives, given the potential for mutual benefit nonetheless.

Indeed, advances in AI depend upon massive computing capabilities, enough data for machines to learn from, and the human talent to operate those systems.94 Today, China leads the world in AI subcategories such as connected vehicles and facial and audio recognition technologies, while Russia has manifest strengths in industrial automation, defence and security applications, and surveillance.95 Based on recent activities and exchanges, there are a growing number of indications that Chinese–Russian collaboration in AI is a priority that should be expected to expand.

- In August 2017, the Russian Robotics Association signed agreements with the China Robotics Industry Alliance and the China Electronics Society with support from China’s Minister of Industry and Information Technology and Russia’s Minister of Industrial Trade.96

- In October 2017, Chinese and Russian experts participated in a bilateral engagement, hosted by the Harbin Institute of Technology and the Engineering University of the Russian Federation, that focused on robotics and intelligent manufacturing, exploring opportunities for future cooperation in those technologies.97

- In April 2018, Russia hosted the Industrial Robotics Workshop for the first time.98 The workshop participants included the leading suppliers of technology and robotic solutions, including Zhejiang Buddha Technology.99 The Chinese participants noted that the Chinese market in robotics is now stronger than ever and advised Russian colleagues to seek help from the state.100

- In May 2019, NtechLab, which is one of Russia’s leading developers in AI and facial recognition, and Dahua Technology, which is a Chinese manufacturer of video surveillance solutions, jointly presented a wearable camera with a face recognition function, the potential users of which could include law enforcement agencies and security personnel.101 According to NtechLab, the company sees law enforcement agencies and private security enterprises among its potential customers.102

- In September 2019, Russian and Chinese partners discussed cooperation in AI at the sixth annual bilateral ‘Invest in Innovation’ forum held in Shanghai. The forum outlined the possibility of a direct dialogue between venture investors and technology companies in Russia and China.103 There, the head of Russian Venture Company (a state investor) noted that ‘artificial intelligence seems to be promising, given the potential of the Chinese market, the results of cooperation, and the accumulated scientific potential of Russia.’104

Biotechnology

Chinese and Russian researchers are exploring opportunities to expand collaboration in the domain of biotechnology. In September 2018, Sistema PJSFC (a publicly traded diversified Russian holding company), CapitalBio Technology (an industry-leading Chinese life science company that develops and commercialises total healthcare solutions), and the Russia–China Investment Fund agreed to create the largest innovative biotechnology laboratory in Russia.105 The laboratory will focus on genetic and molecular research. Junquan Xu, the CEO of CapitalBio Technology, said:

[W]e are honoured to have this opportunity to cooperate with the Russia–China Investment Fund and Sistema … We do believe that the establishment of the joint laboratory will further achieve resource sharing, complementary advantages and improve the medical standards.106

New media and communications

Chinese and Russian interests also converge on issues involving new media. In 2019, Russia intends to submit to the Chinese side a draft program of cooperation in the digital domain.107 China recently hosted the 4th Media Forum of Russia and China in Shanghai with the goal of creating a common digital environment conducive to the development of the media of the two countries, the implementation of joint projects and the strengthening of joint positions in global markets.108 In fact, China’s side discussed joint actions aimed at countering Western pressure against the Russian and Chinese media.109 Both Russia and China aim to develop common approaches and response measures to improve their capacity to promote their point of view—a dynamic that the Chinese Communist Party characterises as ‘discourse power’ (话语权).110 According to Alexey Volin, the Russian Deputy Minister of Digital Development, Telecommunications and Mass Media:

If Twitter, YouTube or Facebook follow the path of throwing out Russian and Chinese media from their environment, then we will have nothing else to do but create new distribution channels, how to think about alternative social networks and instant messengers.111

Such cooperation in new media, internet governance, and propaganda extends from technical to policy-oriented engagements. For instance, at SPIEF–2019, Sogou Inc. (an innovator in research and a leader in China’s internet industry) announced the launch of the world’s first Russian-speaking AI news anchor, which was developed through a partnership with ITAR-TASS, which is Russia’s official news agency, and China’s Xinhua news agency.112 According to the official announcement, the Russian-speaking news anchor features Sogou’s latest advances in speech synthesis, image detection and prediction capabilities, introducing more engaging and interactive content for Russian audiences.113 ‘AI anchors,’ which are starting to become a fixture and feature of China’s media ecosystem, can contribute to the landscape of authoritarian propaganda. During the World Internet Conference in October 2018, China and Russia also plan to sign a treaty involving the Cyberspace Administration of China and Roskomnadzor about ‘combatting illegal internet content.’114

The digital economy

China’s tech giants see business opportunities in Russia’s nascent digital economy. Russia’s data centres are gaining increased capabilities as Chinese companies move into this market. Over the past year, more than 600 Tencent racks have been installed in IXcellerate Moscow One, becoming its largest project. Tencent’s infrastructure will be used for the development of its cloud services and gaming. This project opens up new prospects for Tencent in Russia, which has the highest number of internet users in Europe (about 100 million—a 75% penetration rate).115 All provided services, including the storage and processing of personal data, are expected to be in full compliance with Russian legislation.116 In late 2018, Alibaba Group Holding Ltd started establishing a US$2 billion joint venture with billionaire Alisher Usmanov’s internet services firm Mail.ru Group Ltd to strengthen the Chinese company’s foothold in Russian e-commerce.117 Usmanov is one of Russia’s richest and most powerful businessmen, and his fortunes depend upon the Kremlin’s goodwill as much as on his own business acumen. In this deal, Alibaba signed an accord with Mail.ru to merge their online marketplaces in Russia, which is home to 146 million people. The deal was backed by the Kremlin through the Russian Direct Investment Fund, and the local investors will collectively control the new business.118

Problems in partnership and obstacles to technological development

To date, Sino-Russian cooperation in S&T has encountered some problems. Those issues have included not only insufficient marketisation but also initial Russian reservations about China’s One Belt, One Road initiative, which has been closely linked to scientific and technological collaboration.119 Additionally, there’s evidence that there may still be significant trust issues that impede adopting or acquiring Chinese-made high-tech products for the Russian markets. For example, in a February 2019 interview, Evgeny Dudorov, the CEO of Android Technologies (which built the FEDOR robot), said in a public interview that his company did not want to adopt Chinese robotics parts ‘due to their poor quality’.120

China’s track record over IP theft may be a concern, but it doesn’t seem that Russia is presently as anxious as others about this issue.For instance, Vladimir Lopatin, the Director of the Intellectual Property Department at the Russian Republican Centre for Intellectual Property, sounded a warning about Chinese activities back in 2013:

[T]he prevailing practice of theft and illegal use of Russian intellectual property in the production of counterfeit products by Chinese partners has led to a widespread critical decline in the level of confidence in them from Russian academic and university science centres and enterprises. This is a significant factor in restraining the implementation of strategic initiatives of innovative cooperation between the two countries …121

However, such sentiment does not appear to be so widespread at present. For instance, the Russian media typically concentrates on US–China IP disputes while presenting Sino-Russian high-tech activity in a primarily positive light. Moscow today may be merely resigned, given the long history of Chinese reverse-engineering of Russian defence technologies, but it’s notable that the Chinese Government is publicising promises to enforce IP protection vis-a-vis its Russian counterpart, implying that perhaps a detente has been reached.122 At this point, Russia seems to be more concerned about China possibly stealing its best and brightest scientists—in September 2019, the head of the Russian Academy of Sciences expressed concern that Beijing seems to be successful in starting to attract Russian STEM talent with better pay and work conditions.123 He also seemed concerned that, due to its better organisation and development goals, China was becoming a ‘big brother’ to Russia in not just economic but scientific development and called for a study of China’s overall STEM success.124

At the same time, such bilateral cooperation isn’t immune to the internal politics and certain economic realities in both nations. For instance, in what was obviously an unexpected setback, Tencent admitted back in 2017 it was ‘deeply sorry’ that its social media app WeChat had been blocked in Russia, adding that it was in touch with authorities to try to resolve the issue.125 Russian telecoms watchdog Roskomnadzor listed WeChat on the register of prohibited websites, according to information posted on the regulator’s website. ‘Russian regulations say online service providers have to register with the government, but WeChat doesn’t have the same understanding [of the rules],’ Tencent said in a statement at the time. Equally important is Russia’s ongoing uphill battle in import-substitution of high-tech and industrial components, as a result of the sanctions imposed by the West in 2014 and 2015. Despite significant progress, Russia is still reliant upon Western technology procured by direct or indirect means, and Moscow is not always keen to embrace Chinese high-tech as a substitute.

In Russia, the most lucrative companies are entangled within semi-monoplistic structures close to the Russian Government. Those players are few in number and tend to wield enormous influence in the Russian economy. As a result, the possible high-tech contact nodes between Moscow and Beijing lead through a small number of offices belonging to the most powerful and connected individuals. The true test of the Sino-Russian bilateral relationship concerning high-tech products and services may be in attempting to expand to the medium- and small-sized businesses and enterprises offering the most nimble and capable solutions. For example, the head of Russian Venture Company, a state investor, noted the difficulties in creating tools for a joint venture fund:

We did not resolve the problem of investing in a Russian venture fund. Withdrawing money from China to Russian jurisdictions under an understandable partnership and an understandable instrument is nevertheless difficult.126

Moreover, for both China and Russia, a significant challenge remains: promising young scientists in both countries would prefer to work elsewhere, namely in the US. Some recent polls and anecdotal evidence point to a continuously strong desire for emigration among the best educated, and especially among those with already established international professional relationships.127 This is especially true for Russia. However, as its National Technology Initiative has observed:

We believe that everybody for whom the Californian comfort, sun, wine, mountains and oceans are important has already left Russia. Others realise that the wine, mountains and sea in Sevastopol are just as good.128

For China, the current paradox is that, while Beijing offers plenty of incentives for its STEM community to stay in the country, many researchers choose, in fact, to work overseas, particularly in American institutions.129 The establishment of numerous S&T initiatives outlined in this paper is meant to offset that trend, but the trajectory of so many efforts launched recently remains to be seen.

Conclusions and implications

The Chinese–Russian high-tech partnership may continue to progress in the coming years, as both countries look to leverage each other’s capabilities to advance high-tech developments. China is clearly approaching Russia for its STEM R&D and S&T proficiencies, and Russia seems to be happy to integrate itself more into Chinese high-tech capabilities, and yet it is Beijing that emerges as a dominant player in this bilateral cooperation, while Russia tends to find itself in a position of relative disadvantage. Russia lacks such giants as China’s Baidu, Tencent and Alibaba, which are starting to expand globally, including into the Russian market.130 Nonetheless, as the Russian Government seeks to jump-start its own indigenous innovation, China is seen as a means to an end—and vice versa.

After all, Russian Deputy Prime Minister Maxim Akimov told reporters on the sidelines of the VI Russia–China Expo in Harbin that Russia is interested in cooperation with China in the cybersecurity sphere and in the development of technology solutions: ‘We keep a close eye on the experience of Chinese colleagues.’131

However, the future trajectory of this relationship could be complicated by questions of status and standing, not to mention politics and bureaucracy, as such projects, financing and research accelerate.

Russia may benefit from its embrace of China’s technology prowess and financing, but the full range of risks and potential externalities is still emerging and perhaps poorly understood. As Sino-Russian partnership has deepened, observers of this complex relationship have often anticipated some kind of ‘break’ in the ongoing Russo-Chinese ‘entente’.132 Many commentators find it difficult to believe that countries with such global ambitions and past historical grievances can place much trust in each other.

Certainly, there have been subtle indications of underlying friction, including Russia’s initial reluctance to embrace Xi’s signature One Belt, One Road initiative, to which Moscow has since warmed, or so it seems.

Going forward, high-tech cooperation between Moscow and Beijing appears likely to deepen and accelerate in the near term, based on current trends and initiatives. In a world of globalised innovation, scientific knowledge and advanced technologies have been able to cross borders freely over the past quarter of a century. China and Russia have been able to take advantage of free and open STEM development, from life sciences to information technology and emerging technologies, applying the results to their own distinctive technological ecosystems. Today, however, as new policies and countermeasures are introduced to limit that access, China and Russia are seeking to develop and demonstrate the dividends from a new model for scientific cooperation that relies less and less on foreign, and especially American, expertise and technology, instead seeking independence in innovation and pursuing developments that may have strategic implications.

Policy considerations and recommendations

In response to these trends and emerging challenges, like-minded democracies, particularly the Five Eyes states, should pursue courses of action that include the following measures.

- Track the trajectory of China–Russia tech collaborations to mitigate the risks of technological surprise and have early warning of future threats. This calls for better awareness of Sino-Russian joint high-tech efforts among the Five Eyes states, in conjunction with allies and partners and relevant stakeholders, that goes beyond the hype of media headlines by developing better expertise on and understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of Russian and Chinese technological developments.

- Monitor and respond to tech transfer activities that involve IP theft or the extra-legal acquisition of technologies that have dual-use or military potential, including those activities where there is a nexus between companies and universities with Russian and Chinese links. The US and Australia, along with their allies and partners, should coordinate on export controls, screening of investment and restrictions against collaborations with military-linked or otherwise problematic institutions in China and Russia. Otherwise, unilateral responses will prove inadequate to counter the global threat of Chinese industrial espionage, which is undertaken through a range of tech transfer tactics and is truly international in scope at scale.133

- Deepen cooperation among allies and partners on emerging technologies, including by pursuing improvements in data sharing. The US and Australia should promote greater technological collaboration between Five Eyes governments in the high-tech sectors that are shared priorities in order to maintain an edge relative to competitors. For instance, arrangements for sharing of data among allies and partners could contribute to advances in important applications of AI. To compete, it will be critical to increase funding for STEM and high-tech programs and education in the Five Eyes countries.

- Promulgate norms and ethical frameworks for the use of next-generation technologies, particularly AI, that are consistent with liberal values and democratic governance. In the process, the US and Australia, along with concerned democracies worldwide, should mount a more coordinated response to Russian and Chinese promotion of the concept of cyber sovereignty as a means of justifying repressive approaches to managing the internet and their advancement of AI for censorship and surveillance.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Danielle Cave, Fergus Hanson, Alex Joske, Rob Lee and Michael Shoebridge for helpful comments and suggestions on the paper.

What is ASPI?

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute was formed in 2001 as an independent, non‑partisan think tank. Its core aim is to provide the Australian Government with fresh ideas on Australia’s defence, security and strategic policy choices. ASPI is responsible for informing the public on a range of strategic issues, generating new thinking for government and harnessing strategic thinking internationally.

ASPI International Cyber Policy Centre

ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre (ICPC) is a leading voice in global debates on cyber and emerging technologies and their impact on broader strategic policy. The ICPC informs public debate and supports sound public policy by producing original empirical research, bringing together researchers with diverse expertise, often working together in teams. To develop capability in Australia and our region, the ICPC has a capacity building team that conducts workshops, training programs and large-scale exercises both in Australia and overseas for both the public and private sectors. The ICPC enriches the national debate on cyber and strategic policy by running an international visits program that brings leading experts to Australia.

Important disclaimer

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in relation to the subject matter covered. It is provided with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering any form of professional or other advice or services. No person should rely on the contents of this publication without first obtaining advice from a qualified professional.

© The Australian Strategic Policy Institute Limited 2019

This publication is subject to copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of it may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publishers. Notwithstanding the above, educational institutions (including schools, independent colleges, universities and TAFEs) are granted permission to make copies of copyrighted works strictly for educational purposes without explicit permission from ASPI and free of charge.

- ‘China, Russia agree to upgrade relations for new era’, Xinhua, 6 June 2019, online. ↩︎

- ‘Russia and China celebrate 70 years of the establishment of diplomatic relations’ [Россия и Китай отмечают 70-летие установления дипотношений], TVC.ru, 30 September 2019, online. ↩︎

- Official evening commemorating 70th years of diplomatic relations between Russia and China (Вечер, посвящённый 70-летию установления дипломатических отношений между Россией и Китаем), Official website of the Russian President, June 5, 2019 ↩︎

- This paper uses entirely open sources, and there are inherently limitations in the information that is accessible. Nonetheless, we hope this is a useful overview that leverages publicly available information to explore current trends. ↩︎

Guo, also known as Miles Kwok, fled to the United States in 2017 following the arrest of one of his associates, former Ministry of State Security vice minister Ma Jian. Guo has made highly public allegations of corruption against senior members of the Chinese government. The Chinese government in turn accused Guo of corruption, prompting an

Guo, also known as Miles Kwok, fled to the United States in 2017 following the arrest of one of his associates, former Ministry of State Security vice minister Ma Jian. Guo has made highly public allegations of corruption against senior members of the Chinese government. The Chinese government in turn accused Guo of corruption, prompting an

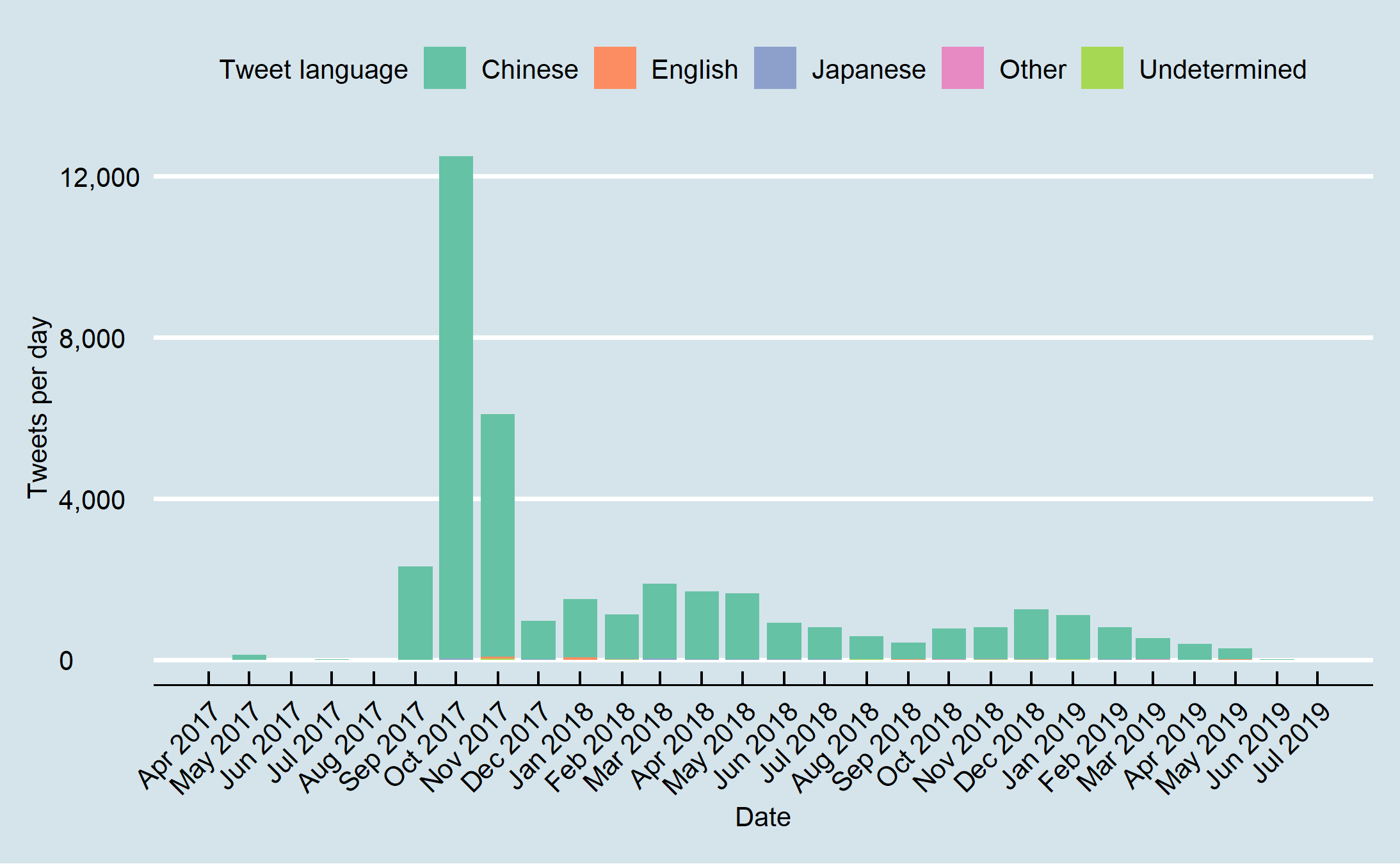

Figure 11: Percent Chinese language tweets per day from Jan 2017 onwards.

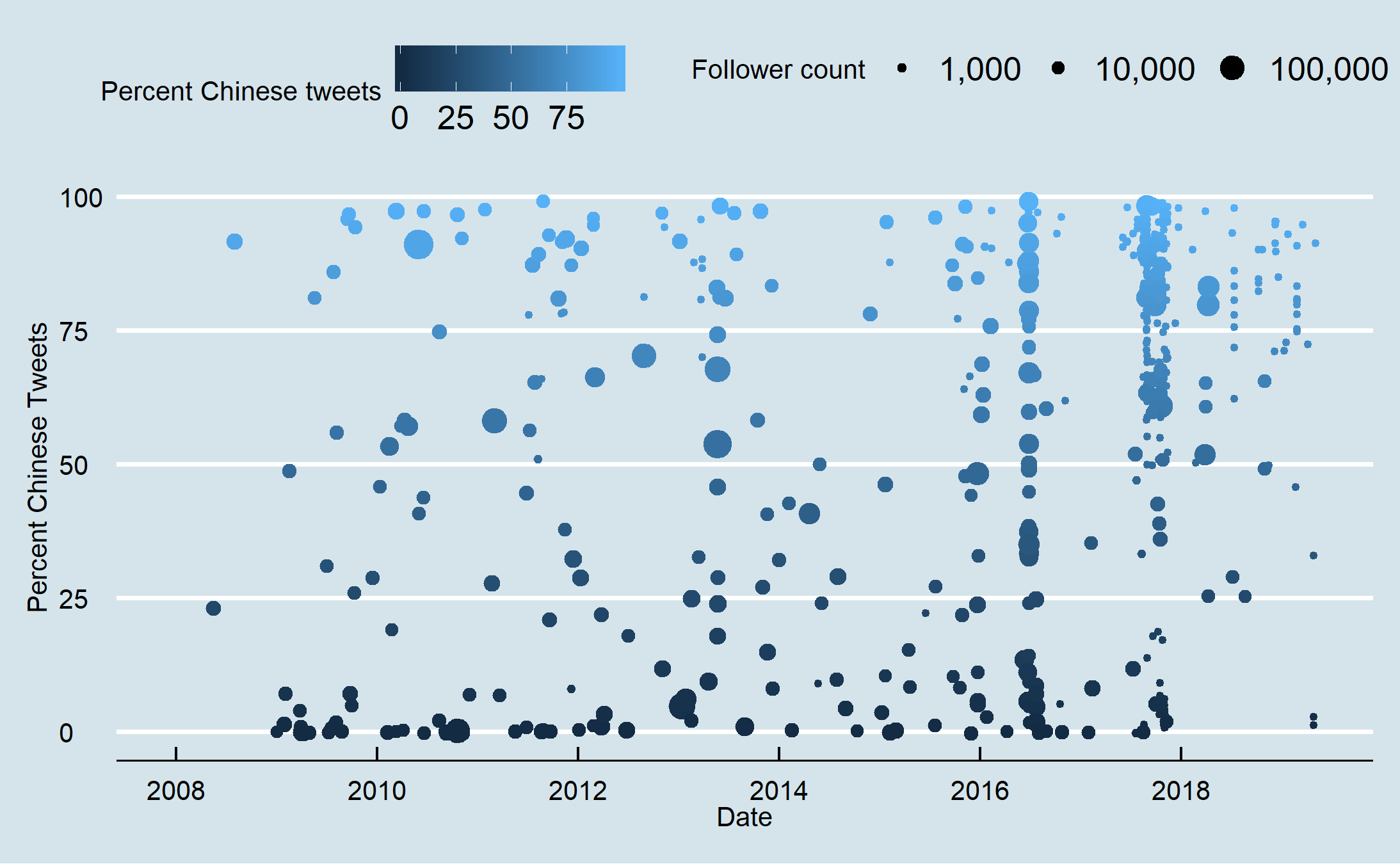

Figure 11: Percent Chinese language tweets per day from Jan 2017 onwards. Figure 12: Account creation day by percent Chinese tweets and follower size from 2008 to July 2019.

Figure 12: Account creation day by percent Chinese tweets and follower size from 2008 to July 2019. Figure 13: Account creation day by percent Chinese tweets and follower size from April 2016 to July 2019.

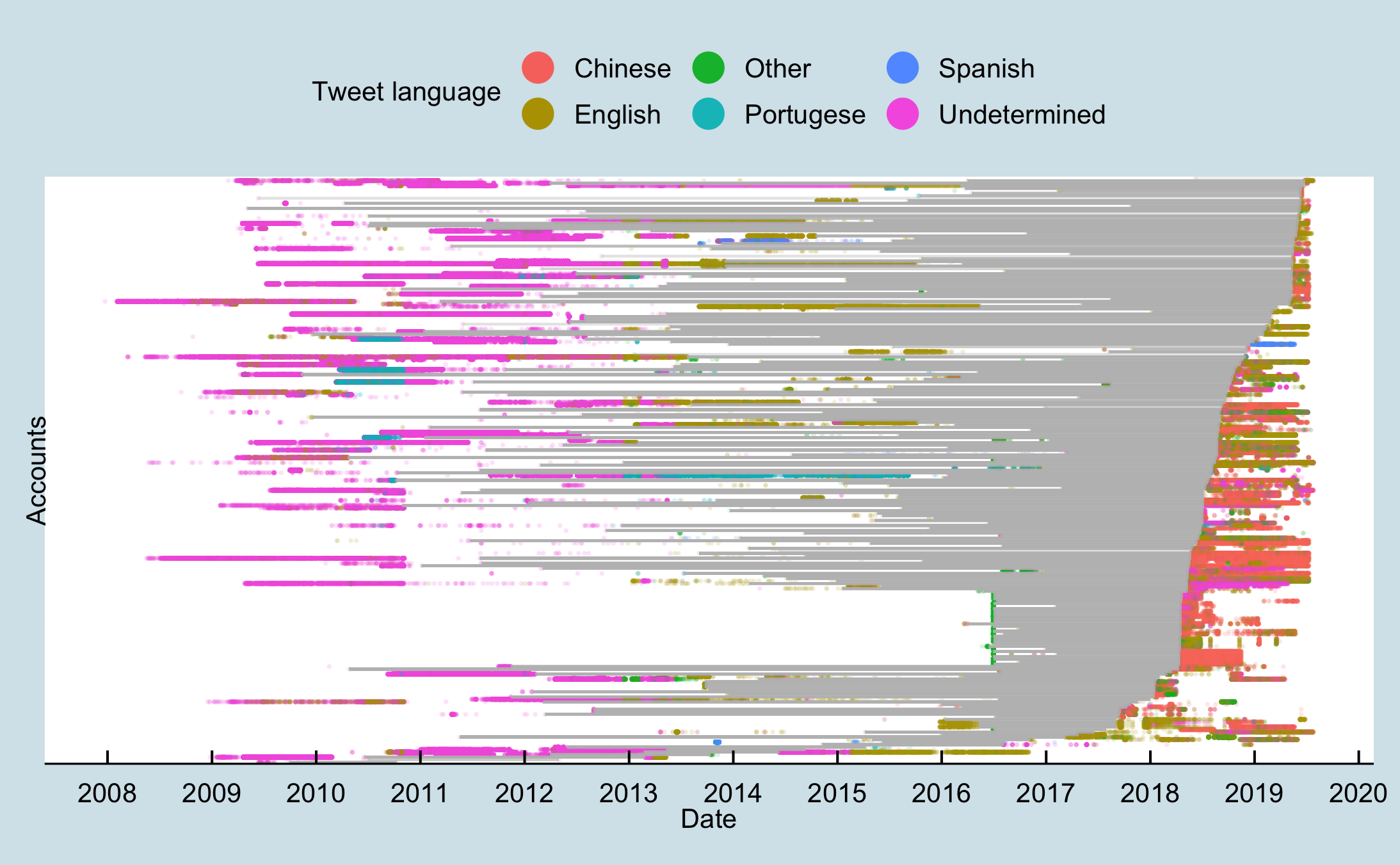

Figure 13: Account creation day by percent Chinese tweets and follower size from April 2016 to July 2019. Figure 14: Tweets over time as represented as dots coloured by tweet language for accounts with a greater than one-year gap between tweets. More than year-long gaps between tweets are represented by grey lines.

Figure 14: Tweets over time as represented as dots coloured by tweet language for accounts with a greater than one-year gap between tweets. More than year-long gaps between tweets are represented by grey lines. Figure 15: Tweets over time as represented as dots coloured by tweet language for accounts with a greater than one-year gap between tweets that were created between June and August 2016.

Figure 15: Tweets over time as represented as dots coloured by tweet language for accounts with a greater than one-year gap between tweets that were created between June and August 2016.