Big data in China and the battle for privacy

Big data in China and the battle for privacy

Introduction

If data is the new oil, China is oil super-rich. Data is the essential ingredient for artificial intelligence (AI) and is underpinning a wide-ranging revolution.

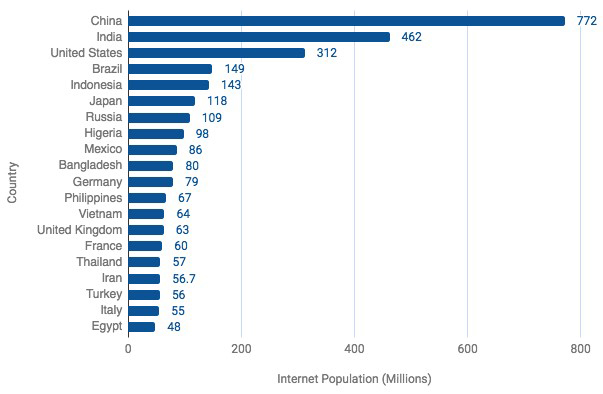

China’s massive population, lack of privacy protections, controlled tech sector and authoritarian system of governance give it a huge edge in collecting the data needed for that revolution (Figure 1). But the Chinese state and Chinese businesses are also using this wealth of data to pursue state and business goals without the constraints present in other jurisdictions. A lack of privacy protections and rule-of-law protections leaves Chinese citizens at the whim of sophisticated, and often state-controlled, data-driven technologies.

Private companies are not only sharing users’ personal data with the authorities in compliance with China’s regulatory environment such as the most recent Cybersecurity Law but many of those companies—including the industry leaders—are building their business model predominantly around the needs of the state.

The success of these technologies in enabling potential mass surveillance and exerting a chilling effect on individuals deserves more attention.

Figure 1: Top 20 internet populations, by country

This paper examines Chinese state policy on big data industries and analyses the laws and regulations on data collection that companies in China are required to comply with. It also looks at how those rules may affect foreign companies eyeing the China market. Case studies are included to demonstrate the ongoing tensions between big data applications and privacy. The paper concludes by outlining the implications and lessons for other countries.

An ambitious big data vision supported by China’s internet companies

China’s State Council has laid out an ambitious road map outlining its AI vision, which includes creating a US$150 billion industry and becoming the world leader in AI by 2030.1 Enormous state financial backing aside, a controlled tech industry,2 huge data availability and relatively scant privacy protections mean that China is well placed to become a global AI leader; or, to be more accurate, a leader in the development of big-data-driven technologies.

China’s online ecosystem is unique compared to Western equivalents. Unlike their Silicon Valley competitors, Chinese technology and internet companies typically design their products to include not just one, but various types of services. Tencent’s WeChat, for example, China’s most popular mobile chat application, is more than an instant messaging app: it’s an all-in-one superapp. A billion active WeChat users now use it to chat with their friends and families, communicate with supervisors and

work colleagues, play games, hail taxis, make online purchases and conduct financial investments.3 WeChat is now even used to handle sensitive government paperwork, such as visa applications, and could soon be used for entry into Hong Kong.4

Tencent vowed—openly and ambitiously—to become the fundamental platform for the Chinese internet: a platform ‘as vital as the water and electricity resources in daily life’.5 Alibaba’s Alipay, China’s Paypal-like e-payment service, has incorporated social functions through which it encourages users to share location data, personal information and purchasing habits with others. Combined with China’s real-name registration system,6 these consolidated functions enable the government and industry

to effortlessly profile individual users. In addition, even when an individual’s information has been anonymised, their identity can still be re-identified by any interested parties if they have access to two or more sets of data to find the same user in both. In other countries, such identification would attract public concern, but research indicates that there’s a lack of awareness and a willingness to trade off privacy for lower cost services among Chinese consumers.7 For example, research that compared global consumers’ views on sharing personal information online found that consumers in China had a more lackadaisical attitude towards privacy protection than consumers in most Western countries.8

Big data analytics offers invaluable insights to inform the use and delivery of public goods, including increased public safety, law enforcement, resource allocation, urban planning9 and healthcare systems.10 But how data is collected and used affects a country’s digital ecosystem and its citizens’ social and political participation. How China’s regulatory environment handles these interactions is analysed in the following section.

Big data and public security

China is placing huge bets on big data, and a range of policies have been introduced over the past two years to flesh out the government’s vision. On October 18 2017, Chinese President Xi Jinping promoted the integration of the internet, big data and AI with the real-world economy in his 19th Party Congress report.11 But China’s interest in big data can be dated to as early as the early 2010s. In July 2012, the State Council specifically mentioned the importance of ‘strengthening the development of basic software—especially those that are able to handle large volumes of data’—in a policy document in its 12th Five-Year Plan . The current administration has beefed up the conceptualisation of China’s big data vision.

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang, for example, proposed the concept of ‘Internet Plus’ (互联网+),12 calling for the integration of mobile internet, cloud computing, big data and the ‘internet of things’ with modern manufacturing in his March 2015 Government Work Report.13

In the months following Li’s report, China’s central government released a number of top-down designs and guidelines on big data policies (Table 1). By the end of 2016, various government bureaucracies 14 and more than 20 provincial and municipal governments issued their own regulations and development plans for big data industries.15 Unsurprisingly, most of these government initiatives and policies have a special interest in developing and supporting big data technologies that can be applied to the security sector. Security experts argue that contribution to the emerging social credit system is likely as part of these related initiatives.16 Statistics from 2016 show that most of the government’s domestic government investment in big data industries has gone to public security projects.17

Table 1: Major big data policies issued by the Chinese Government

| Title | Issuer | Date issued | Main takeaways |

| Made in China 2025 《中国制造2025》, online | State Council | May 2015 | Lays out a road map for the transformation and upgrade of China’s traditional and emerging manufacturing industry, with a focus on big data, cloud computing, the internet of things and related smart technologies. (a) |

| Action Outline for Promoting the Development of Big Data 《促进大数据发展行动纲 要》, online | State Council | August 2015 | Provides a top-down action framework for promoting big data. Details yearly goals such as establishing a platform for sharing data between government departments by the end of 2017, a unified platform for government data before the end of 2018, and nurturing a group of 500 companies in the industry, including 10 leading global enterprises focused on big data application, services and manufacturing by the end of 2020. It is widely perceived to be a programmatic document guiding the long-term development of China’s big data industries. |

| Outline of the 13th Five-Year Plan for the National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China 《中华人民共和国经济和 社会发展第十三个五年规 划纲要》, online. | National People’s Congress | March 2016 | Identifies big data as a ‘fundamental strategic resource’ (基础性战略资源). Pushes for further sharing of data resources and applications. Lists big data applications as one of the eight major informatisation projects. It’s the first time China incorporated big data into state-centric strategy plans. (b) |

| The National Scientific and Technological Innovation Planning for the 13th Five Years 《’十三五’国家创新规划》, online. | State Council | July 2016 | Prioritises big-data-driven breakthroughs in AI technologies. |

| Development Plan for Big Data Industries (2016–2020) 《大数据产业发展规划 2016-2020年)》, online. | Ministry of Industry and Information Technology | December 2016 | Sets an overarching goal for China’s big data industries: by 2020, related industry revenue should exceed 1 trillion RMB, with a compound annual growth rate of 30%. |

a) 徐永华,陈怀宇, 陈亦恺, Anthony Marshall, 何志强,夏宇飞, 温占鹏,张龙,孙春华, ‘中国制造业走向2025 构建以数据洞察为驱动的新价值网络’,IBM商业价值研究院, 中国电子信息产业发展研究院, 13 October 2015 online.

b) 林巧婷, ‘我国首次提出推行国家大数据战略’ 中央政府门户网站, 3 November 2015 online.

In the outline of the 13th Five-Year Plan, big data applications were listed as one of the eight major ‘informatisation’ projects. Informatisation (信息化)—the process by which the political, social and economic interactions in a society have become networked and digitised—cannot be overstated when analysing China’s big data vision, especially in the public security sector. Over the past two decades, the Ministry of Public Security has taken an adaptive approach to this trend. It has made continuous efforts18 to harness the advances of information and communications technologies for security operations—a process called ‘public security informatisation’ (公安信息化). At its core, public security informatisation relates to shifting police work from reactive to pre-emptive through the use of data collection and synthesis. “Security” is a broad concept when applied by the Chinese state and is sufficiently broad to enable the control and censoring of public debate in ways that may affect the power or standing of the ruling Chinese Communist Party.

A few statistics help put these concepts and policies in context. Across China, there’s a network of approximately 176 million surveillance cameras—expected to grow to 626 million by 202019—that monitor China’s 1.4 billion citizens. Powered by big-data-driven facial recognition technology, these cameras are able to identify a person’s name, identification card number, gender, clothing and more. Meanwhile, Chinese police have reportedly been collecting DNA samples, fingerprints, iris scans, and blood types of all residents, using questionable methods, in places such as Xinjiang.20

Backed by an oceanic amount of data and advanced analytic technologies, Chinese public security forces are emerging as a powerful and dominant intelligence and security sector.21 The interest from the public security forces in using big data to support government systems for faster and more extensive surveillance and social control largely explains the rapid rise of China’s big data industries.22

Private companies are not only sharing users’ personal data with the authorities in compliance with China’s Cybersecurity Law,23 the National Intelligence Law24 and other relevant internet management regulations, but many of them—including the industry leaders25—are building their business model predominantly around the needs of the state.

Diminishing rights: China’s data laws and regulations

On the other end of the spectrum of the all-encompassing, data-driven analytic technologies are citizens’ de facto diminishing rights to privacy and growing challenges of protecting individuals’ data security. In contrast to the wide scope of central- and local-level policy initiatives and government-backed projects on big data collection and use, there’s no uniform law or a national authority to ensure or coordinate data protection in China. Privacy advocates have been striving to have a national privacy protection law passed since 2003.26 Fifteen years later, the National People’s Congress, China’s highest legislative body, still has not included such uniform law in its agenda.27

A number of articles in China’s recent Cybersecurity Law pertain to data collection and privacy protection. However, they take a state-centric approach, expanding the government’s direct involvement in companies’ operations. Missing in this approach is any support for an independent privacy watchdog or support for independent civil society organisations. For now, regulations on data protection remain largely domain-specific, such as those relating to telecommunications and online banking, which are issued by different ministries or local governments (Table 2 summarises the main relevant regulations in China).

Table 2: Chinese laws, regulations and guidelines on data collection

| Title | Issuer | Date issued | Relevance |

| Information Security Technology: Guidelines for Personal Information Protection Within Public and Commercial Services Information Systems 《信息安全技术公共及商用服务信息系统个人信息保护指南》, online. | General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine & Standardisation Administration of China | Nov 2012 | Establishes basic principles for personal data collection, processing and transfers, including the principles of ‘parity of authority and responsibility’, ‘minimum necessary and not excessive’ and ‘consent of the individual’. Remains non-compulsory for companies |

| Decision on Strengthening Information Protection on Networks 《关于加强网络信息保护的 规定》, online. | Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress | Dec 2012 | Specifies that the state protects ‘electronic information by which individual citizens can be identified and which involves the individual privacy of citizens’. |

| Provisions on Protecting the Personal Information of Telecommunications and Internet Users 电信和互联网用户个人信息保护规定, online. | Ministry of Industry and Information Technology | July 2013 | Regulates how telecommunications and internet service providers may collect and use users’ personal data. |

| Regulation on the Administration of Credit Investigation Industry 征信业管理条例, online. | State Council | Jan 2013 | Encompasses China’s grand plan of building a ‘social credit system’. Regulates the collection, storage and processing of personal information by credit investigation enterprises. Article 14 points out that ‘credit investigation institutions are prohibited from collecting information about the religious belief, genes, fingerprints, blood type, disease or medical history of individuals, as well as other individual information the collection of which is prohibited by laws or administrative regulations.’ |

| Amendment (IX) to the Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China 刑法修正案(九), online. | Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress | Aug 2015 | Criminalises the sale or provision of citizens’ personal data, with a penalty of up to seven years imprisonment. |

| Cybersecurity Law 网络安全法, online. | Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress | Nov 2016 | Article 76 (5) defines ‘personal information’ in legal documents for the first time. ‘Personal information’ refers to all kinds of information, recorded electronically or through other means, that can determine the identity of natural persons independently or in combination with other information, including, but not limited to, a natural person’s name, date of birth, identification number, personal biometric information, address and telephone number. |

| E-commerce Law (draft) 电子商务法 (草案) | Under review by Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress | May be passed in 2018 | Regulates data collection by e-commerce operators |

| Interim Security Review Measures for Network Products and Services 《网络产品和服务安全审查办法(试行)》, online. | Cyberspace Administration of China | May 2017 | Specifies that a cybersecurity review will include reviewing risks that product or service suppliers illegally collect, store, process or use user-related information while providing products or services. |

| Information Security Technology: Personal Information Security Specification 《信息安全技术 个人信息安全规范》, online. | General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine & Standardisation Administration of China | Dec 2017 (took effect in May 2018) | Clarifies the definition of ‘personal sensitive information’, which includes information on one’s wealth, biometrics, personal identity, online identity identifiers and so on. Remains non-compulsory for companies |

The lack of a legal framework on privacy protection has led to open disputes over who has access to user data. One of the most high-profile cases is the dispute between Tencent, China’s first internet giant to enter the elite US$500 billion tech club,28 and Huawei, the Chinese telecom equipment and smartphone maker. Huawei was seeking to collect user data from Tencent’s WeChat, China’s most popular chat app, installed on its Honor Magic phone. The data would help Huawei advance its AI projects. Tencent was quick to object, claiming it would violate user privacy and demanded that the Chinese Government intervene.29 Huawei argued that users have the right to choose whether and with whom their data is shared. The government suggested the two companies ‘follow relevant laws and regulations’,30 but existing regulations fail to specify who can collect and process user data.31 It’s still unclear how the two settled the dispute—or even whether they’ve settled it.32

Huawei and Tencent aren’t the first Chinese tech giants to rub shoulders other over access to data. In June 2017, Alibaba’s logistics arm, Cainiao, and China’s biggest private courier, SF Express, were in a month-long stand-off over access to consumer data. The fight was eventually resolved with the State Post Bureau’s intervention.33 Cainiao and SF Express both cited noble-sounding reasons, such as ‘data security’ and ‘user privacy’, for refusing to share data with each other, but the dispute was really about protecting their commercial interests and determining who had access to merchant and shopper data on China’s US$910 billion online retail market.34 In the case of Huawei versus Tencent, it’s about who may get to dominate the AI race with the help of massive amounts of data, including users’ chat logs. Due to a void in the current legal framework, it’s likely that disputes between companies over user data access will continue.

Lack of transparency and accountability

Most of the regulations are aimed at holding companies and individuals—rather than government bodies—accountable for data collection and protection. By contrast, government authorities now have access to more sensitive personal data than ever (through either court orders or surveillance). In addition, law enforcers are requiring companies to ensure a longer period of data retention and zero exemptions from real-name registration policies.

In June 2016, for example, China’s Cyberspace Administration issued the Provisions on the Administration of Mobile Internet Applications Information Services (移动互联网应用程序服务管理规定),35 which require, among other things, that:

- app providers and app stores cooperate with government oversight and inspection

- app providers keep records of users’ activities for 60 days

- app providers ensure that new app users register with their real names by verifying users’ mobile phone numbers, other identifying information, or both.

In September 2016, Chinese authorities issued new regulations stating explicitly that user logs, messages and comments on social media platforms such as WeChat Moments—a feature that resembles Facebook’s timeline feed—can be collected and used as ‘electronic data’ to investigate legal cases.36 Cases of WeChat users being arrested for ‘insulting police’37 or ‘threatening to blow up a government building’38 on Moments indicate that the feature may be subject to monitoring by the authorities or the company.

Observers have raised concerns over authorities’ use of big-data-driven and AI-enabled technologies such as facial recognition and voice recognition, which may lead to an all-seeing police state. iFlytek, a Chinese information technology company designated by the Ministry of Science and Technology to lead the country’s speech recognition development, has partnered with the Ministry of Public Security to develop a joint research lab. According to a report by the company, it has also partnered

with local telecommunication companies in eastern Anhui Province to establish a surveillance system that ‘notifies public security departments as soon as a suspicious voice is detected’.39 In the highly restricted Xinjiang region, local authorities are reportedly collecting highly sensitive personal information, including DNA samples, fingerprints and iris scans.40

A case that demonstrates ongoing tensions between big data applications and privacy concerns in China is the building of a national social credit system 社会信用体系 (SCS), which is the subject of a forthcoming ICPC policy brief by Samantha Hoffman. The SCS, currently planned for a full launch by 2020, aims to aggregate data on the country’s 1.4 billion citizens and assign each person a credit rating based on their socioeconomic status and online behaviour.41 So far, there’s little detail on exactly

how the system will unfold. Some companies and local governments have created their own systems (such as Tencent’s Tencent Credit,42 Alibaba’s Sesame Credit43 and many other social credit products developed by smaller players).44 While a final reward and punishment mechanism remains uncertain, existing reports show some consistent themes. For example, based on their social credit score and behaviours that affect one’s credit, a citizen’s access to aeroplane or express train travel will be denied and their privileges, such as faster visa approval and easier access to apartment rentals, will be restricted if the person has a bad social credit score.

The justifications for this scheme include the idea that it’s a remedy for the deficit of trust in society.45 Southern Metropolis Daily, a Guangzhou-based liberal-leaning newspaper, surveyed 700 people on their attitudes towards China’s social credit system in 2014.46 It found that even though 40% of the respondents expressed privacy concerns, 80% were in support of this national program because ‘it helps build a society of trust’ and ‘provides a safer and more reliable environment for business’. Yet, the complete lack of transparency and clarity on data protection raise the alarming prospect of big-data-enabled mass surveillance in China and other authoritarian states.

Both Alibaba47 and Tencent48 have rolled out their own versions of social credit systems, which offer a holistic assessment of character based on vaguely defined categories and non-transparent algorithms.49 According to material collected by researchers at the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab, the chief credit data scientist of Alibaba’s Ant Financial, Yu Wujie, has said, ‘If you regularly donate to charity, your credit score will be higher, but it won’t tell you how many payments you need to make every month … but [development] in this direction [is undertaken with] the hope that everyone will donate.’50 Tencent has revealed little about its credit system thus far, but the company already has access to a huge amount of users’ social data, including chat logs, via WeChat, QQ and many of its gaming products.

Due to the lack of data protection laws, few, including state regulators, have an understanding of what kinds of data a private company can access and use.51 It’s also unclear whether online comments and activities deemed undesirable by the government would negatively affect a person’s creditworthiness. The scheme is wide open to abuse by government authorities, including in tracking dissidents and exerting chilling effects on ordinary citizens.52

International implications

The tensions between privacy protection and data collection will be felt not only in China. In recent years, companies and governments in both authoritarian and democratic countries have vowed to develop big-data-based surveillance technologies and tighten internet management in the name of public and national security.53

At the international level, cross-border transfers of personal information, courtesy of the increasingly interdependent global economy in the age of big data, have become a pressing issue for private and state actors. Following the enactment of the Cybersecurity Law, which sets data localisation requirements, China has released administrative documents and guidelines detailing the conditions companies need to meet for data export (Table 3).

Table 3: Regulations on cross-border data transfer or data export

| Title | Issuer | Date issued | Relevance |

| Cybersecurity Law 网络安全法, online. | Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress | Nov 2016 | Article 37: Personal information and important data collected and generated by critical information infrastructure operators in China must be stored domestically. For information and data that is transferred overseas due to business requirements, a security assessment will be conducted in accordance with measures jointly defined by China’s cyberspace administration bodies and the relevant departments under the State Council. Related provisions of other laws and administrative regulations shall apply. |

| Circular of the State Internet Information Office on the Public Consultation on the Measures for the Assessment of Personal Information and Important Data Exit Security (Draft for Soliciting Opinions) 《个人信息和重要数据出境 安全评估办法(征求意见稿)》, online. | Cyberspace Administration of China | Apr 2017 | Extends the scope of outbound data security assessment. While the Cybersecurity Law requires security evaluations to be conducted on critical information infrastructure operators (关键信息基础设施运营者), the measures stipulate that all network operators (网络运营者) must go through the check. Establishes the basic framework for outbound data security assessment, including its processes, responsible parties and main focuses. |

| Information Security Technology: Guidelines for Data Cross-Border Transfer, online. Security Assessment (second draft), online. 《信息安全技术 数据出境安 全评估指南 (第二稿)》 | National Information Security Standardisation Technical Committee | Aug 2017 | Clarifies the definition of data cross-border transfer, which is ‘the one-time or continuous activity in which a network operator provides personal information and important data collected and generated by network or other means in the course of operations within the territory of China to overseas institutions, organisations or individuals by means of directly providing or conducting business, providing services or products, etc.’ Further breaks down the conditions for initiating security self-assessment, government assessment and their processes. Details what is ‘important data’ and ‘personal data’. Non-compulsory for companies. |

Under these regulations, foreign companies will have to either invest in new data servers in China that may be subject to monitoring by the government or incur new costs to partner with a local server provider, such as Tencent or Alibaba. Apple’s recent decision to migrate its China iCloud data to Guizhou Big Data and Amazon’s sell-off of its China cloud assets to its local Chinese partner are just two examples of how China’s tightening rules on data retention and transfers may affect foreign companies. By requiring data localisation, the Chinese Government is bringing data under Chinese jurisdiction and making it easier to access user data and penalise companies and individuals seen as violating China’s vaguely defined internet laws and regulations.

Meanwhile, Chinese-manufactured tech devices and applications that have taken over large portions of overseas markets are raising questions about data security. The Australian Defence Department has recently banned staff and serving personnel from downloading WeChat, China’s most popular social media app, onto their work phones.54 The heads of six top US intelligence agencies, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Central Intelligence Agency and the National Security Agency, told the Senate Intelligence Committee in February that they would not advise Americans to use products or services from Chinese telecommunications companies Huawei and ZTE. In April 2018, the tension escalated into a seven-year ban imposed by the US Commerce Department, prohibiting American companies from selling parts and software to ZTE, although at the time of publishing it’s unclear whether this ban will be enforced or overturned.55 In December 2017, the Ministry of Defence in India issued a new order to the Indian armed forces requiring officers and all security personnel to remove more than 42 Chinese apps, including Weibo, WeChat and UC Browser, which were classified as ‘spyware’.

Conclusion

This paper highlights the conflict between the fast-developing big data technologies and citizens’ diminishing rights to privacy and data security in China. A review of major Chinese big-data-related policy initiatives shows that many of those policies reflect special interest from Chinese authorities, its public security forces in particular, in potentially using data-driven analytic technologies for more effective and extensive surveillance and social control.

Compared to the growing number of regulations and national plans that support the research and development of big data technologies, there’s a lack of data protection laws and guidelines to hold relevant parties, especially the government, accountable for the collection and use of personal data. The ambivalent legal framework of data security and privacy protection, which enables state use of collected data, has led to multiple incidences of commercial disputes over access to users’ data. It’s likely we’ll see more such cases in the future.

Addressing these conflicts and advocating for the protection of users’ rights to privacy in China—where the state dominates every sector of society and suppresses civil society—is not easy. The Chinese state’s approach is a reminder to users, both in China and elsewhere, of the importance of protecting personal privacy and online security.

Using China as a case study also offers a number of takeaways for policymakers in other countries. International developments, such as ongoing privacy issues with Facebook data, show that tension between governments, businesses and users in the age of big data is not unique to any country. To that end, the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation has set a good example for containing companies’ exploitation of personal data.

There’s a trend, in China and elsewhere, for governments to use the excuse of ‘protecting user privacy’ to justify a more powerful state and more state involvement in private companies’ and organisations’ operations. Civil society groups, whenever and wherever possible, should assume a stronger role in addressing these challenges and raising awareness . A US-based study released in April 2018, for example, highlighted consumer misconceptions about privacy while using popular browsers, including that they would ‘prevent geo-location, advertisements, viruses, and tracking by both the websites visited and the network provider’.56 Further work and support are needed to equip users with sufficient knowledge to understand how data-related technologies work and what those technologies mean to them in everyday life.

The attractiveness of the Chinese state’s surveillance and social control systems to other authoritarian states means we may see other states adopt them, unless the negative aspects of these approaches are made more transparent. The consequences of reduced personal freedom combined with greater state control of societies and individuals are disturbing for advocates of the vitality and strength of open societies. Beyond these concerns, the strategic consequences of the tight integration of the

Chinese tech sector with the Chinese state is an area for further analysis.

Important disclaimer

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in relation to the subject matter covered. It is provided with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering any form of professional or other advice or services. No person should rely on the contents of this publication without first obtaining advice from a qualified professional person.

© The Australian Strategic Policy Institute Limited 2018

This publication is subject to copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of it may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publishers.

- 中华人民共和国国务院, ‘国务院关于印发 新一代人工智能发展规划的通知’, 国务院, 8 July 2017, online. ↩︎

- China has permitted only some foreign direct investment through Chinese entities with partial or full foreign ownership in many tech sectors. See more detailed analysis by Paul Edelberg, ‘Is China Really Opening Its Doors to Foreign Investment?’, China Business Review, 8 November 2017, online and Jianwen Huang, ‘China’, The Foreign Investment Regulation Review – Edition 5, October 2017, online. ↩︎

- Yang Ruan, Cheek, Social media in China: what Canadians need to know; Nicole Jao, ‘WeChat now has over 1 billion active monthly users worldwide’, Technode, 5 March 2018, online. ↩︎

- Mason Hinsdale, ‘Tencent wants to make WeChat a digital travel ID’, Jing Travel, 6 June 2018, online. ↩︎

- 马化腾, ‘互联网像水和电一样成为‘传统行业’, Digitaling.com, 12 August 2014, online. ↩︎

- Catherine Shu, ‘China attempts to reinforce real‑name registration for internet users’, Techcrunch.com, 1 June 2016, online. ↩︎

- Hui Zhao, Haoxin Dong, ‘Research on personal privacy protection of China in the era of big data’, Open Journal of Social Sciences, 19 June 2017, 5:139–145, online. ↩︎

- Boston Consulting Group, Data privacy by the numbers, March 2014, online. ↩︎

- Linda Poon, ‘Finally, Uber releases data to help cities with transit planning’, CityLab.com, 11 January 2017, online. ↩︎

- Linda Lew, ‘How Tencent’s medical ecosystem is shaping the future of China’s healthcare’, Technode.com, 11 February 2018, online ↩︎