Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

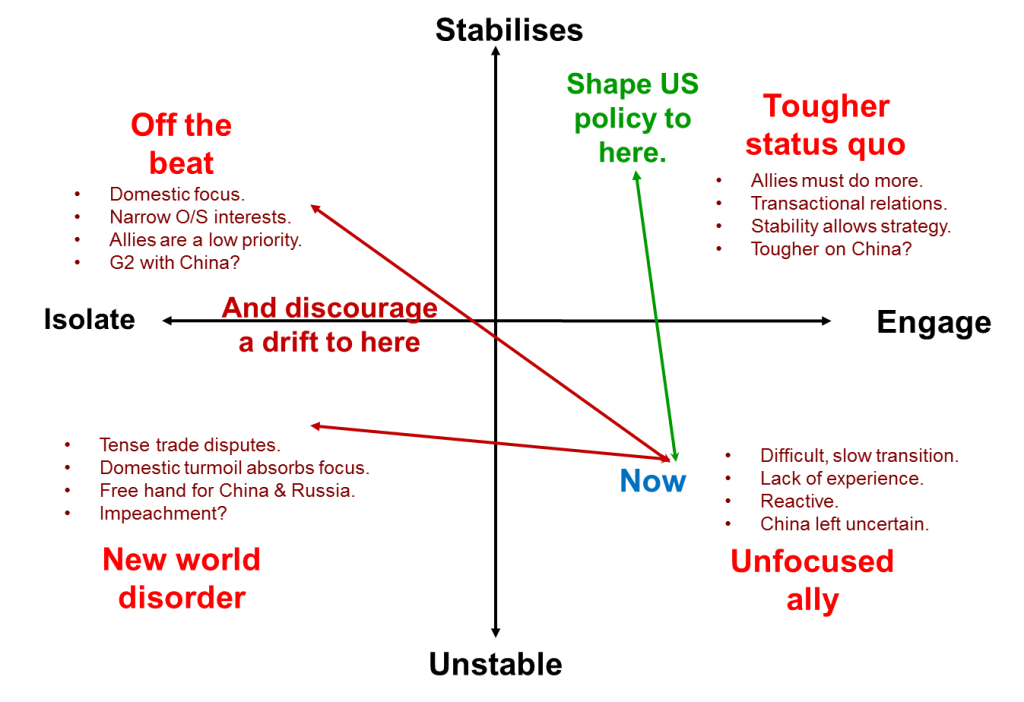

At ASPI’s recent State of the Region Masterclass (PDF) I detailed some “alternate futures” for the Trump administration. In truth no-one, not even Trump himself, can be sure how his presidency will evolve. The future is unknowable, which is why using scenario tools that consider a range of alternate futures can be useful when considering Australia’s options for dealing with Trump.

Two key considerations will shape the long term character of the administration. The first is the extent to which Trump shapes a foreign policy of engagement with friends and allies or one which takes a relatively more isolationist bent. The signals are confused. Trump has certainly been critical of key allies, claiming they don’t carry enough of the security burden, but the President’s engagement with Shinzo Abe, Theresa May, Justin Trudeau and Malcolm Turnbull (hard going though that phone call was) all suggest a warming towards traditional allies. The Germans must be worried after Merkel’s awkward meeting—this is one key relationship that isn’t improving. Trump had an equally rocky start with China, but now Washington has reasserted its support for the One China policy which may allow for a more productive meeting between Trump and Xi Jinping. Trump’s comments about wanting to build a productive relationship with Putin are naïve considering the strategic differences between the two countries. For much of the rest of the world, the administration’s views are unknown. Trump harbours a suspicion—not without some foundation—that the outside world just sponges off the US.

The second key consideration shaping the character of the administration is whether it will stabilise into a more normal pattern of business or if Trump’s plan is to deliberately stay unstable. Again, there are contrary signs. Secretaries Mattis, Tillerson, Allen and National Security Adviser, Lieutenant General McMaster—the key national security players—look like reassuring professionals. But Trump was elected precisely because he ran a disruptive campaign; he’s continuing that approach with rallies and social media focused on his support base.

The intersection of those key driving forces—engagement or isolationism; organisational stability or disorder—point to four possible futures for the Trump administration. Right now the Presidency is unstable but it’s still engaging key partners. Think of this scenario as the world of the Unfocused Ally. The administration’s lack of focus means that it faces a difficult and slow transition to office: it took 50 days before Trump’s Cabinet met and literally thousands of political appointments are yet to be made. Key administration figures are starting from a very low knowledge base about international affairs. An Unfocused Ally will be reactive, unpredictable and keep friends and rivals constantly guessing about Washington’s next move. The One China policy? The two-state solution? Don’t expect finesse.

It’s possible that Trump will grow into the job. If the administration becomes more stable and engages allies, its approach will evolve into a Tougher Status Quo. We’ll see greater expectations of allies. Secretary Mattis recently delivered this message to NATO: ‘It is a fair demand that all who benefit from the best alliance in the world carry their proportionate share of the necessary costs to defend our freedoms.’ In this world Washington will be more transactional, more inclined to judge allies by their last military contribution to Coalition efforts and less motivated by the idea of historic alliances. Greater stability means that over time the administration may be less reactive and better able to develop strategic approaches to key relationships. Trump may develop a tougher policy towards Chinese adventurism than Obama—not that that’s saying much. In fact Beijing would probably prefer a consistent but tougher Washington than remaining in a cloud of confusion about the President’s next Tweet.

Moving over to the left hand side of the scenario diagram, an administration that becomes more isolationist and more stable in delivery becomes the cop Off the Beat. With a dominant domestic focus, this is an America in which traditional allies would lose relevance. China, Russia and Iran would look to consolidate attempts to dominate their neighbours. Japan, Germany and Australia, among others, must rethink their own security postures, assuming that the US would be less supportive. Trump might see this environment as a great place to practice the Art of the Deal internationally. Can he cut a deal with China? ‘You get Southeast Asia and we get trade protectionism.’ That would be a worrying place, but would enable the President to play to the voters that elected him.

The final scenario is New World Disorder, in which the administration swings to isolationism and sustains—or deepens—its instability. Just as Lenin understood, disorder can be a deliberate but risky tactic. Trump’s campaign was essentially an insurgency against the American political establishment. A number of his key staff, like senior adviser Steve Bannon, will continue that approach. There’s no point worrying about appointing hundreds of administration officials if the broader aim is to govern with a tiny cadre of ideologues in the White House. In the New World Disorder allies would struggle to gain attention. The administration might act on its rhetoric to ramp up trade disputes and Russia, China and others would have a freer hand for their strategic objectives. The administration would use instability as a tactic to sustain its anti-Washington voter base, but surely Congress would fight back. Impeachment may lie ahead as Trump struggles to accept that running a country is different to running a tight family business.

We shouldn’t pretend that Australia can shape much of that, but our interest is to do what we can to push the administration towards the stable and engaged scenario of the Tougher Status Quo and away from the isolationist scenarios. We can do that by making sure Malcolm Turnbull builds an effective relationship with Trump. We’ll have to do more in terms of alliance cooperation (our own strategic interests demand this), but rather than wait for America to set the price Canberra should design its own agenda for doing more together.

Is that what Australia will do? The signs are mixed. Unlike many world leaders Turnbull hasn’t yet gone over to Mar-a-Lago for a round of golf. He may calculate that there’s nothing in it for him domestically to get too buddy-buddy with Trump. A well-organised chorus of useful idiots in Australia are counselling Turnbull to distance himself from the US and embrace the world’s Chinese future. Too much of that and Trump might decide that isolationism is the right way to handle flaky allies. That, folks, would be neither great nor beautiful.

We were in Washington recently for the latest annual track-2 ‘Quad Plus’ dialogue. The meeting brings together participants from think tanks in Australia, India, Japan and the United States, as well as invited “plus” nations—this year we had representatives from Singapore. (Reflections on previous meetings are here and here.)

This round of talks comes at an important time, with the Quad democracies (and in fact many democracies around the world) facing a series of difficult challenges. In the 12 months since the previous meeting we’ve seen Russia consolidate its position in Crimea and eastern Ukraine through clever use of deniable ‘grey zone’ warfare. And China now has a series of fortified outposts in the South China Sea (SCS), having summarily dismissed the legitimacy of last year’s Arbitral Tribunal finding against it. As well, many democracies are facing internal electoral insurgencies that consume bandwidth and distract from global issues.

Because of our shared values and similar political institutions, it’s easy to find common ground with our colleagues from the other Quad countries—despite the fact that we all have our own parochial issues and security challenges. So the question becomes how to harmonise our efforts to address the common challenges.

One of the most intriguing ideas floated in this year’s meeting came from the US side in a fine paper on South China Sea issues by Professor James Kraska from the US Naval War College. He proposes a three-pronged response to China’s unilateral activities in the SCS. Two of the points are familiar to us: supporting and supplementing American Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS) and leveraging the legal high ground provided by the 2016 Arbitral Tribunal ruling on China’s claims.

Consistent with those two approaches, Kraska argues that other countries (including the other Quad countries) should conduct FONOPS to reinforce the internationally established laws of the sea. The logic is that because FONOPS generate—or at least help sustain—public goods, the burden should be shared between the nations that benefit from those goods. And making sure that any FONOPS conform to the findings of the PCA ruling would help to underpin the rule of law that we collectively seek to preserve.

While there’s no doubt that the Tribunal ruling can and should feature prominently in our diplomatic representations on the SCS, FONOPS will likely remain a contentious option for Australia and others. But we were most intrigued by Kraska’s third idea: the use of lawful countermeasures. Countermeasures, in this sense, are actions to impose a cost on states that interfere with other’s rights under international law. In order to qualify as lawful, acts must be proportionate, not disadvantage innocent third parties, and conform with broader international norms, such as respect for human rights.

In the SCS, China is restricting the rights of other nations conferred by UNCLOS—specifically, the right to innocent passage in territorial seas and passage without restriction in an EEZ. At the moment, it does so without incurring any costs beyond diplomatic protests. A lawful response by other states could take the form of imposing similar restrictions on Chinese vessels and aircraft in their EEZ and territorial waters. In practice, that would mean physically shadowing Chinese platforms and asking them to leave. To be clear, we’re talking about searchlights and loudspeakers, not shots across the bow.

We like this idea for a number of reasons. First, it imposes a symmetry on the situation that’s lacking at the moment. Second, it doesn’t increase tensions in the vicinity of third party territories and claims. But the most compelling reason is that it reverses the asymmetry of interests that bedevils the cost–benefit calculus of FONOPS within Chinese-claimed waters.

Rightly or wrongly, China has convinced itself that the SCS is a core interest, and has been increasingly assertive in defence of that interest. The strength of feeling that has been engendered within Chinese society would make it very hard for its government to cede ground now. FONOPS help to delegitimise any legal claim that China has to the waters around occupied features, but since the Tribunal decision, we know that the legal niceties are of secondary importance to China. Deliberations about FONOPS have to factor in the potential of an aggressive Chinese response, and subsequent escalation risks. It’s possible that a FONOP would have to be abandoned for reasons of safety or prudence, but such a back down would seriously undermine the point trying to be made.

Many of those concerns don’t apply in the case of Chinese vessels being challenged in other nation’s waters. The asymmetry of territorial interest would be reversed, adding to the credibility of resistance. And the potential for escalation would be much more in the hands of the country employing the countermeasure. It would be a clear assertion of the rights that we value, but with considerably lower risk than FONOPS in Chinese-claimed waters.

There’s nothing about legal countermeasures that restricts their application to the Quad countries. In principle, it’s a strategy that any country could implement. But the Quad countries are well placed to pursue the strategy by virtue of their naval and maritime air capabilities. Individually it would be a useful form of signalling; collectively it could be very powerful indeed. It’s an idea worth thinking about—and worth recalling the next time the debate about FONOPS rears its head.

Happy #IWD2017 for Wednesday, y’all. It’s no accident that all of this week’s picks are either about women or by women. Let’s dive in.

The Economist has gifted us with their annual Glass Ceiling Index to show where women have the ‘best chances of equal treatment at work’. The Nordic nations still lead the pack, while Japan and South Korea are all the way down the other end; Australia’s somewhere in the middle, though below the OECD average. Feast your eyes on where the surveyed nations sit with respect to measures including working environment, education, wage gap, paid leave, and women on boards and in parliaments.

Let’s stay with Japan for a minute. Another survey released this week had some more poor news in store when it ranked Japan 163rd out of 193 countries for female representation in parliaments, down from 156/191 the previous year. So things aren’t great, but one shining example—indeed, a diamond in the rough—is Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike. The FT visited Koike, a former LDP Diet member, at her Tokyo pad to talk life and politics, but it was her dog, So-chan, who stole the show. Over at The Interpreter, Krystal Hartig checks in on PM Abe’s efforts to increase female participation through his ‘womenomics’ initiative. And for the Council on Foreign Relations, Sheila Smith has pulled together short bios on seven women who’ve led the way in promoting an understanding of Japan. On the list is the former US Ambassador to Japan, Caroline Kennedy, who championed gender equality while at post. Read more about Kennedy in this recent NYT profile.

Masha Gessen’s occasional column for The New York Review of Books has quickly become one of the must read voices on Russia. Catch up with her latest, on the Trump-Kremlin conspiracy (cover-up?), here.

There’s a good chance that International Women’s Day was acutely felt in Washington DC this year. With Hillary Clinton back in the press after a quiet few months, declaring that ‘the future is female,’ the World Economic Forum has highlighted the goals that must be achieved before we can realise that future. White House national security aide Sebastian Gorka has repeatedly reveled in his belief that ‘the alpha males are back’ in charge of international relations under Trump. In a piece over at POLITICO, three of Washington’s Alpha Females—Wendy Sherman, Michèle Flournoy and Madeleine Albright—dissect Trump’s machismo-infused policy approach and, unsurprisingly, find it wanting. (For more, see the podcast recommendation). Also on female superstars from America’s officialdom, Quartz has published a list, based on CIA report from 1984, of seven outstanding female spies, who may have had a thing or two to say about the return of the “alpha male”.

A round of applause for our friends over at Lowy for their all-women line-up on 8 March. For our money, Danielle Cave’s article on the banishing the ‘all-male panel’ stole the show. For those keen to break the manel’s back, Danielle lists four excellent resources: one, two, three and four. We’d also like to add the exceptional Foreign Policy Interrupted—sign up for their weekly mail-out for a smorgasbord of world-class analysis from exceptional women in the defence, foreign policy and security fields. And finally, on 20 March, readers can look forward to the release of Foreign Policy’s first-ever women’s issue.

ASPI this week launched a new series on Women, Peace and Security. In week one we’ve served up analysis from think-tankers, ADF members, academics and officials, with more to come as the debate unfolds over the next couple of weeks. As always, we’re keen to improve the quality of the debate by featuring the work of female students, analysts, academics, commentators and strategists. Please get in touch (editors@aspi.org.au) if you want to write for The Strategist.

Podcasts

Two good picks featuring America’s first female Secretary of State, the unflagging Madeleine Albright. First is a new drop from David Axelrod’s fantastic podcast, The Axe Files; Albright talks about her experience as a political refugee fleeing Czechoslovakia for the UK in the 1940’s, US power, Trump’s agenda and Steve Bannon (63 mins). In the second, Albright is part of a high-powered troika alongside Michèle Flournoy and Wendy Sherman; the three talk alpha-male natsec policy, their experiences as top-ranking female officials, and America as an ‘indispensable nation’, among others (45 mins).

The stellar team that brings you the ‘Bombshell’ podcast was this week joined by military history heavyweight Kori Schake to dissect Kim Jong-nam’s assassination in Malaysia and, as always, offer thoughts on their top tipples for the week. Check it out here (50 mins).

Video

In celebration of #IWD2017, CSIS’s Smart Women, Smart Power project hosted the Managing Director of the IMF Christine Lagarde for a chat about empowering women in the workplace, and policies and procedures that might help to achieve that end. Watch how the conversation unfolded here (57 mins).

Events

Brisbane: We’re getting a good run-up to this event because it’s sure to be a corker: Griffith University will host Texas A&M’s Valerie Hudson on 2 May for a presentation on the Hillary Doctrine, WPS and gender in foreign policy in the time of Trump. After her remarks Hudson will continue the discussion with the dynamic duo of Sara Davies and Susan Harris Rimmer. Registration essential; details over at Twitter.

Melbourne: Join Linda Jakobson and Bates Gill as they launch their new book, China Matters: Getting It Right For Australia. The powerhouse team will be answering your questions at the State Library of Victoria on 30 March.

Welcome back to your weekly fix of cyber news, analysis and research.

The New York Times reported last Saturday that, back in 2013, President Barack Obama ordered cyber sabotage operations against Pyongyang’s nuclear weapons program. The persistently high failure rate of the US’s kinetic antimissile weapons, despite significant investment, reportedly prompted Obama to consider a cyber supplement. The project to pre-emptively undermine missiles in their development stages, known as a ‘left of launch’ strategy, receives dedicated resources at the Pentagon and is now President Trump’s to play with. However, experts are concerned that this kind of cyber offensive approach sets a dangerous precedent for Beijing and Moscow, particularly if they believe that US cyber operations could successfully undermine their nuclear deterrence capability.

Staying stateside, the future of the NSA’s spying powers are under scrutiny this week as elements of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) approach sunset. Section 702 of the Act forms the basis for the NSA’s monitoring of foreign nationals’ communications around the globe in the interests of national security. It was under this FISA authority that the US’s infamous “big brother” program PRISM—revealed in the Snowden disclosures of 2013—was established.

While the legislation is designed for foreign targets, there have long been concerns it could be used to surveil US citizens through their contact with foreigners. Human rights advocates such as the American Civil Liberties Union are protesting the renewal of this legislation in defence of international privacy. The issue also has the trans-Atlantic data-sharing agreement on thin ice, especially given that EU Justice Commissioner Vera Jourova has made it clear that she ‘will not hesitate’ to suspend the painstakingly crafted arrangement should the US fail to uphold its stringent privacy requirements.

That task may be even more difficult after WikiLeaks’ overnight release of a dossier, dubbed ‘Vault 7’, detailing the CIA’s cyber espionage tools and techniques. WikiLeaks released over 8,000 documents it claims were taken from a CIA computer network in the agency’s Center for Cyber Intelligence. The documents detail the agency’s expansive and sophisticated cyber espionage capability, including compromising the security common devices and apps including Apple iPhones, Google’s Android software and Samsung televisions to collect intelligence.

China’s Foreign Ministry and the Cyberspace Administration of China this week launched the country’s first International Strategy of Cooperation on Cyberspace. The Strategy outlines China’s basic principles for cyber diplomacy and its strategic goals in cyberspace. Encouragingly, the Foreign Ministry’s Coordinator for Cyberspace Affairs Long Zhao stated that ‘enhancing deterrence, pursuing absolute security and engaging in a cyber arms race…is a road to nowhere’. Unsurprisingly, the Strategy offers strong support for the concept of cyber sovereignty, stating that ‘countries should respect each other’s right to choose their own path of cyber development’, and emphasises the importance of avoiding cyberspace becoming ‘a new battlefield’. You can read a full English language version of the Strategy here.

The revelation that the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) was temporarily forced to rely on diesel generators during last month’s heat wave has prompted the government to significantly upgrade to the agency’s infrastructure. The Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for Cyber Security told Parliament on Wednesday that it was recommended by ActewAGL and the NSW Department of Environment that ASD switch to back up power on 10 February as part of state-wide load shedding to protect power supplies. The new $75 million project, funded by the Defence Integrated Investment Program, is intended to bolster the intelligence agency’s resilience.

Several cyber incidents have kept the internet on its toes this week. The Amazon Simple Storage Service cloud hosting service went down last week, knocking hundreds of thousands of popular websites and apps offline. The disruptive incident, originally described by the company as ‘increased error rates’, was actually not the result of cyber criminals or hacktivists, but that of an employee’s fat fingers entering a command incorrectly—whoops! Yahoo is in the doghouse (again) with the awkward announcement in its annual report to the Security and Exchange Commission that 32 million customer accounts are thought to have been compromised through forged cookies. This isn’t to be confused with the entirely separate and very embarrassing loss of 1 billion accounts in a 2013 breach, which recently cost the company $350 million in its acquisition deal with Verizon and CEO Marissa Mayer her annual cash bonus. And if you’ve been tracking the #cloudbleed saga, catch up with some post-mortems here, here and here.

Finally we’ve got you covered for your weekly cyber research reads. A new Intel report, written by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, examines the discrepancies in cyberspace that put defenders at a disadvantage. Titled Tilting the Playing Field: How Misaligned Incentives Work Against Cybersecurity, the report reveals the gaps between attackers vs. defenders, strategy vs. implementation and executives vs. implementers, offering recommendations to overcome such obstacles. And get your fix of statistics from PwC’s annual Digital IQ assessment based on a survey of more than 2,000 executives from across the world. The research reveals that only 52% of companies consider their corporate Digital IQ to be ‘strong,’ a considerable drop from 67% last year.

In 2014, China denied market access to several Hong Kong artists who had supported their home city’s democracy movement. Chinese state media commented: ‘You can’t eat at our table and knock over our rice pot!’

Such rhetoric wasn’t quite about table manners. Rather, it summarised the implied terms and conditions for entry into the Chinese economy. If a private entity or a sovereign state challenges what China perceives as its “core interests”, then China might sometimes “sanction” it by restricting its access to the Chinese market. While such a sanction usually won’t cause long-term damage (PDF) to another country’s domestic industry (because a market will often correct itself), it can create turbulence that lasts for several years—especially if the other country relies on China for export trade.

There’s a list of countries that China considers at particular times to be unworthy of eating at its table. In early December 2016, China imposed additional customs charges on exporters from Mongolia, following the Dalai Lama’s visit to that country. In November 2016, China banned various films and entertainers from South Korea, and this was recently observed to have intensified into a wider ban against Korean entertainment programs on Chinese media. In response to criticisms, a Chinese official reportedly commented that Korea ‘needs to firstly solve the THAAD problem’. After Taiwan elected a new president in January 2016, China was observed to start restricting its own tourists from visiting Taiwan. Since 2012, China intermittently restricted banana imports from the Philippines, apparently in response to the latter’s position on the South China Sea. Empirical research (PDF) has further suggested a ‘Dalai Lama effect’: if a country’s head of State meets with the Tibetan spiritual leader, then its exports to China will be reduced by 8–17% percent in the next two years.

The extent of Australia’s export dependence on China makes it potentially vulnerable to such manoeuvres. In 2015, 30.2% of Australian goods exports and 14.9% of service exports were destined for China (PDF). Such dependence is even stronger than Australia’s dependence on the United Kingdom market before the UK decided to join the European Economic Community (for example in 1960-61, 23.9 percent of Australian goods exports were destined for the UK (PDF)). Further, the major Australian exports (iron ores, education, tourism, etc.) aren’t indispensable to China and can be sourced from elsewhere.

In contrast, China’s reliance on the Australian market is insignificant: only 1.8% of Chinese exports (goods and services) were destined for Australia in 2015. Nevertheless, Australia is the second-largest host country of Chinese investment (as of 2015), and 49% of such investments were from Chinese state owned enterprises (PDF).

While it’s generally accepted that international trade can promote peace, a proviso is that the trading parties must be economically interdependent. In the absence of such interdependence, trade can become an instrument capable of generating conflict instead of peace.

Australia’s dependence on the Chinese market provides leverage for China’s political aspirations, and that vulnerability is understood within China. In July 2016, Chinese state media commented, in the context of Australia’s position concerning its ‘biggest trading partner’ in the South China Sea, that Australia is an ‘ideal target for China to warn and strike’.

Australia’s options to counterbalance such manoeuvres are limited. Since access to the Australian market is of less importance to China, a ‘tit-for-tat’ strategy that similarly limits China’s market access to Australia will be ineffective. A complaint to the World Trade Organization might succeed, but the legal process can take two years to complete.

Australia might, in a way similar to its sanction regime against Russia, limit certain commercial activities of the entities established in Australia by Chinese investors, especially those with strong ties with the Chinese government. However, such a move may invite China to adopt similar measures, and endanger Australian investment in China.

Australia might adopt collective countermeasures (PDF) in collaboration with other countries, especially those who share Australia’s position on a specific international issue. Examples of such measures include the sanctions against Russia during the Ukraine crisis by Australia, the European Union, Japan and the United States; and the sanctions (PDF) against Argentina during the Falklands crisis by Australia, Canada, the European Community, New Zealand, the UK and the US. While Australia’s positive international image might place it in a good position to call for such collaborations, it’s unsafe to assume that a Chinese sanction can attract the sympathy similar to those concerning the armed conflicts in Ukraine or the Falklands. The recent tension on the US–Australia relationship further questions whether an international collaboration can be easily achieved.

To solve the root of this problem, Australia needs to address its dependence on the Chinese market. Whereas artificially restricting its trade with China would be unwise, Australia needs to cultivate greater trade interdependence with China, and to diversify its trade relations by negotiating further trade deals with other economies. Now is an opportune time, since trade agreements are currently being reconsidered internationally following Brexit and the Trump election. In this connection, much can be learnt from Australia’s own trading history: recall that China has only become Australia’s biggest trading partner since 2009.

It’s not too late for Australia to adjust its trade approach now. But before that can be achieved, Australia must carefully balance the needs of its two masters: its trade relations on one hand, and its values and security interests on the other.

Michael Flynn’s recent fall from grace opened the door for yet another General to join the Trump administration. Since the President announced that H.R. McMaster will take on the role of National Security Advisor, portraiture of the oft-described “soldier-scholar” has piled up. One effort from POLITICO paints a picture of a strong-willed intellectual, a man of discipline, history, independence and ethics. On the back of that profile, George Packer for The New Yorker asks, ‘Can a free mind survive in Trump’s White House?’ If you’re short on time, McMaster was the topic of conversation for a snappy 5 on 45 podcast from Brookings’ Michael E. O’Hanlon (5 mins). And to get a grip on how McMaster sees the world, catch up with these four articles he penned between 2008 and 2015 for IISS’s Survival journal; this NYT op-ed on war as political, human and uncertain; and this speech on future war delivered to CSIS last year.

Fans of The Dish (2000–2015) will have been pleased to see that Andrew Sullivan has started a new weekly ‘experiment’, which he says is in the ‘the British magazine tradition of a weekly diary — on the news, but a little distant from it, personal as well as political, conversational more than formal.’ Week one of the series ‘on life in Trump’s America’ considered lies; week two, Kremlin–White House links. *bookmarked*

China’s plan to revise its 1984 Maritime Traffic Safety Law—essentially grabbing the pen and trying its hand at rewriting some of Asia’s rules—is ruffling feathers worldwide. The revision will push for the following:

‘Foreign submersibles should travel on the surface, display national flags and report to Chinese maritime management administrations when they pass China’s water areas, the draft says. They should also get approval from the relevant administration to enter China’s internal waters and ports’

Sichuan University’s Yang Cuibai has noted that the draft will allow China to take the lead in creating legal precedents in its waters, which he understands to include both the East and South China seas. This week saw the Asian superpower finish construction of nearly two-dozen storage units on Subi, Mischief and Fiery Cross reefs, which are expected to house long-range surface-to-air missiles. At least the US still has the soft-power monopoly, right? Wrong. With China set to overtake the US by year’s end on the metric of highest grossing country at the box office, it’s worth listening to the latest ‘ChinaPower’ podcast from CSIS, where Bonnie Glaser and Stan Rosen take a look at the soft power of Chinese cinema. And one more for Sinophiles: check out this excellent longread on where Trump should focus his energies as he seeks to reset US–China economic relations.

Finally, we know you’re doing alright if you’re tuning in for ASPI suggests each week, but if you’ve ever thought you need to diversify your news intake, here are two handy tools to help you out. The first is a new initiative from BuzzFeed called ‘Outside Your Bubble,’ which will show readers of popular BuzzFeed news articles the opinions of others from Twitter, Facebook, Reddit and more, to help them burst free of their digital echo chambers. The second, from Alphabet’s Jigsaw incubator, is called ‘Unfiltered.News,’ and uses Google News data to create a map of the most prominent topics and headlines from across the globe. Happy reading, strategists!

Podcasts

Latrobe Asia’s podcast, Asia Rising, recently sat down with former ONA boss Allan Gyngell to talk Australian foreign policy and Canberra’s efforts in Asia (16 mins). There’s likely no-one better when it comes to extemporising on our external affairs—he literally [co-]wrote the book, and recently put down some thoughts on the Foreign Policy White Paper process.

Hosted in NYC rather than their usual studio high above Dupont Circle, the latest installment from Foreign Policy’s ‘The E.R.’ podcast series (38 mins) seeks to sift fact from fiction to determine whether the USA has actually become a reality show.

Videos

Vowing to bring viewers ‘the stories behind the research,’ Brookings’ Creative Lab YouTube channel recently kicked off a new series called Unpacked, where the think tank’s experts shed light on issues in the news cycle. Two recent offerings look at the US Department of Homeland Security’s plans to implement Trump’s EO (4 mins), and “sanctuary cities” (4 mins).

Events

Canberra (but also, across Australia): International Women’s Day will be almost upon us on 8 March, and tickets to country-wide events run by UN Women are selling quickly. Each event will feature all-star panels of women excelling in their fields, as well as a delicious meal. What’s not to like?! Make sure you register your interest now so you don’t miss out.

Brisbane: Brissie-based readers shouldn’t miss their chance to get a handle on just how the Trump administration might make its mark on the Japan-Australia strategic relationship. Japanese Consul-General Hidehiro Hosaka will join the AIIA at the Queensland Multicultural Centre in Kangaroo Point this coming Tuesday evening to lay it all down.

If there is one thing at which China’s leaders truly excel, it is the use of economic tools to advance their country’s geostrategic interests. Through its $1 trillion ‘one belt, one road’ initiative, China is supporting infrastructure projects in strategically located developing countries, often by extending huge loans to their governments. As a result, countries are becoming ensnared in a debt trap that leaves them vulnerable to China’s influence.

Of course, extending loans for infrastructure projects is not inherently bad. But the projects that China is supporting are often intended not to support the local economy, but to facilitate Chinese access to natural resources, or to open the market for low-cost and shoddy Chinese goods. In many cases, China even sends its own construction workers, minimizing the number of local jobs that are created.

Several of the projects that have been completed are now bleeding money. For example, Sri Lanka’s Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport, which opened in 2013 near Hambantota, has been dubbed the world’s emptiest. Likewise, Hambantota’s Magampura Mahinda Rajapaksa Port remains largely idle, as does the multibillion-dollar Gwadar port in Pakistan. For China, however, these projects are operating exactly as needed: Chinese attack submarines have twice docked at Sri Lankan ports, and two Chinese warships were recently pressed into service for Gwadar port security.

In a sense, it is even better for China that the projects don’t do well. After all, the heavier the debt burden on smaller countries, the greater China’s own leverage becomes. Already, China has used its clout to push Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Thailand to block a united ASEAN stand against China’s aggressive pursuit of its territorial claims in the South China Sea.

Moreover, some countries, overwhelmed by their debts to China, are being forced to sell to it stakes in Chinese-financed projects or hand over their management to Chinese state-owned firms. In financially risky countries, China now demands majority ownership up front. For example, China clinched a deal with Nepal this month to build another largely Chinese-owned dam there, with its state-run China Three Gorges Corporation taking a 75% stake.

As if that were not enough, China is taking steps to ensure that countries will not be able to escape their debts. In exchange for rescheduling repayment, China is requiring countries to award it contracts for additional projects, thereby making their debt crises interminable. Last October, China canceled $90 million of Cambodia’s debt, only to secure major new contracts.

Some developing economies are regretting their decision to accept Chinese loans. Protests have erupted over widespread joblessness, purportedly caused by Chinese dumping of goods, which is killing off local manufacturing, and exacerbated by China’s import of workers for its own projects.

New governments in several countries, from Nigeria to Sri Lanka, have ordered investigations into alleged Chinese bribery of the previous leadership. Last month, China’s acting ambassador to Pakistan, Zhao Lijian, was involved in a Twitter spat with Pakistani journalists over accusations of project-related corruption and the use of Chinese convicts as laborers in Pakistan (not a new practice for China). Zhao described the accusations as ‘nonsense.’

In retrospect, China’s designs might seem obvious. But the decision by many developing countries to accept Chinese loans was, in many ways, understandable. Neglected by institutional investors, they had major unmet infrastructure needs. So when China showed up, promising benevolent investment and easy credit, they were all in. It became clear only later that China’s real objectives were commercial penetration and strategic leverage; by then, it was too late, and countries were trapped in a vicious cycle.

Sri Lanka is Exhibit A. Though small, the country is strategically located between China’s eastern ports and the Mediterranean. Chinese President Xi Jinping has called it vital to the completion of the maritime Silk Road.

China began investing heavily in Sri Lanka during the quasi-autocratic nine-year rule of President Mahinda Rajapaksa, and China shielded Rajapaksa at the United Nations from allegations of war crimes. China quickly became Sri Lanka’s leading investor and lender, and its second-largest trading partner, giving it substantial diplomatic leverage.

It was smooth sailing for China, until Rajapaksa was unexpectedly defeated in the early 2015 election by Maithripala Sirisena, who had campaigned on the promise to extricate Sri Lanka from the Chinese debt trap. True to his word, he suspended work on major Chinese projects.

But it was too late: Sri Lanka’s government was already on the brink of default. So, as a Chinese state mouthpiece crowed, Sri Lanka had no choice but ‘to turn around and embrace China again.’ Sirisena, in need of more time to repay old loans, as well as fresh credit, acquiesced to a series of Chinese demands, restarting suspended initiatives, like the $1.4 billion Colombo Port City, and awarding China new projects.

Sirisena also recently agreed to sell an 80% stake in the Hambantota port to China for about $1.1 billion. According to China’s ambassador to Sri Lanka, Yi Xianliang, the sale of stakes in other projects is also under discussion, in order to help Sri Lanka ‘solve its finance problems.’ Now, Rajapaksa is accusing Sirisena of granting China undue concessions.

By integrating its foreign, economic, and security policies, China is advancing its goal of fashioning a hegemonic sphere of trade, communication, transportation, and security links. If states are saddled with onerous levels of debt as a result, their financial woes only aid China’s neocolonial designs. Countries that are not yet ensnared in China’s debt trap should take note—and take whatever steps they can to avoid it.

Central Asia’s economy has functioned well since the global financial crisis of 2009. Kazakhstan’s credit rating is still at an investment grade. Uzbekistan has continued to grow at a rate of roughly 8% since the crisis and Tajikistan has maintained growth of 5–7% since 2009. That has been achieved during a tough time for the global economy with negative interest rates, sluggish growth and greater protectionism.

China has seen Central Asia’s potential and sought out economic opportunities for itself and the region. In 2015, it created the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) with the intent of financing US$8 trillion worth of vital infrastructure, mainly in Central Asia. The AIIB attracted 57 members, including United States allies like Australia and Great Britain despite complaints from the US and Japan about the bank’s governance, relative to the rival US–Japanese Asian Development Bank. However, with the election of Donald Trump and the potential US withdrawal from Asia’s financial architecture, the AIIB now seems to be a diplomatic master stroke from China.

China now needs to ensure that the bank actually contributes to Central Asia’s economic development. China’s way of doing this will be through the ‘one belt, one road’ (OBOR) initiative. The initiative has two objectives. Firstly, to revitalise the ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ that runs through Central Asia. Secondly, to connect this belt with the new ‘Maritime Silk Road’ that runs through the Indian Ocean. If the AIIB is to finance the significant infrastructure deficit in Central Asia, China will lay the groundwork for achieving the first objective of the OBOR initiative.

Reestablishing the dormant Silk Road Economic Belt will be the greatest test for OBOR. The Indian Ocean is an established hub for international trade and fisheries that Australia helps protect. The Silk Road now only links China’s Xinjiang and Pakistan and converting that into a vibrant trade route will be hard. Even if the necessary infrastructure is built through AIIB investment, the Silk Road Economic Belt will still have to have to procure funding from more traditional bilateral sources and private investors. That’s a tough ask for an infrastructure project already planned to be ‘multiple times larger’ than the Marshall Plan.

However if the Silk Road Economic Belt does develop the required infrastructure, the economies of Central Asia will benefit significantly. Central Asia might again provide the lifeblood of the international economy and the region will have China’s OBOR to thank for it. China’s political objectives for OBOR are clearly to develop allies in Central Asia.

To understand China’s economic diplomacy in Central Asia, it’s worth looking at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). The SCO was started by China and Russia in 2001 to create a multilateral security organisation akin to NATO between the two countries, as well as Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. The focus of the SCO has been mainly on security to combat the ‘three evils’ of terrorism, separatism and extremism, and its member states have started sharing intelligence and conducting joint military exercises.

While the SCO remains focussed on security, the bloc has recently become more comprehensive and its members have formed a strategy to harmonise the economies of Central Asia, mainly through the AIIB. China has pushed for a free trade agreement among members and Russia appears to be keen to integrate its Eurasian Economic Union with China’s OBOR initiative to bolster its struggling economy.

That has improved trust among the members. In June 2016, China’s state-owned Xinhua News Agency spoke of a regional identity, a ‘Shanghai Spirit’ defined by ‘mutual trust, mutual benefit, equality, consultation, respect for diverse civilizations and pursuit of shared development.’ It won’t be surprising if China tables a document like ‘ASEAN Vision 2020’ at the SCO soon to formalise a regional identity similar to that of the Southeast Asian regional bloc.

If China succeeds in prosecuting its diplomatic agenda, the four pillars for a regional bloc will have been built, namely: financial architecture (through the AIIB); significant regional trade (through the Silk Road Economic Belt and an SCO free trade agreement); security architecture (through intelligence sharing and joint military operations at the SCO); and a regional identity (through the Shanghai Spirit).

Such a bloc could become a serious competitor to the Indo–Pacific’s existing architecture. As East Asia’s economies struggle with deflation, ageing populations and asset bubbles, multilateral organisations like ASEAN and APEC might find a fast-growing economic competitor in the SCO. Another threat is that, unlike ASEAN and APEC, the SCO’s focus has always been on security. As such, a regional bloc in Central Asia might carry more strategic weight than the existing multilateral economic organisations in the Indo–Pacific.

While those threats might only be realised much further down the track, the SCO has the potential to weaken ASEAN and APEC. As a founding member of APEC and a longtime advocate for better integration in ASEAN through the East Asia Summit, Australia should appreciate how those developments will affect the regional architecture. That will be vital if Australia is to understand how best to advance its interests in an evolving Indo-Pacific.

It’s 20 January, Inauguration Day in the United States, and nobody now doubts that we’re destined to live in what the Chinese would call ‘interesting times’. The new president’s campaign rhetoric strongly intimated that under his self-proclaimed ‘America First’ posture, traditional American strategy and alliance politics would undergo a major change. And what’s already clear is that his approach to dealing with allies and adversaries will be based less on their traditional roles in US foreign policy and more on how he and his foreign and security policy team view other countries’ willingness to adjust their policies to conform with a markedly different set of US economic and strategic priorities.

As part of Trump’s revised posture, there appears to be a greater readiness to embed US power and policy within a more multipolar international power structure—albeit with less emphasis on the importance of international institutions to US policy interests. He’s already criticised the United Nations for ‘not living up to its potential and…causing problems rather than solving them.’ Still, notwithstanding reports of Russian cyber-meddling in the American electoral process assisting Trump’s campaign victory, the president-elect’s desire to seek accommodation with Russia (over likely opposition from key congressional Republicans), suggests nothing less than a radical adjustment to America’s position in the world.

The incoming administration’s geopolitical outlook on the Asia–Pacific is no less seminal. Trump’s musings over the utility of the US’s longstanding ‘one China’ policy as the core principle for governing Sino–American relations, and his equally controversial acceptance of a phone call from Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen, strongly signalled that no concrete ‘grand bargain’ would be immediately engineered between his government and the People’s Republic of China. That point has also been underscored in the confirmation testimony of his Secretary-of-State designee, Rex Tillerson, who warned that China must stop its island-building in the South China Sea. He further asserted that the US would seek support from its regional security allies to ensure that China doesn’t employ what reclaimed islands it has constructed to disrupt the flow of maritime trade through the region.

Indeed, the president-elect’s cabinet and national security choices point to the adoption of a US foreign policy management style more comparable with that of the business world than with one driven by classic geopolitics. In this context, Trump’s campaign threat to slap substantial tariffs on Chinese exports to the US in retaliation for what he viewed to be Chinese currency manipulation, and his appointment of Peter Navarro, a strong critic of China’s trade and security policies, as director of the White House’s National Trade Council, underscored the contrast in the incoming president’s perspectives of China and Russia. Trump has jettisoned President Barack Obama’s promotion of the multilateral Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement as a basis for underwriting US trading and commercial interests in Asia. Perhaps most fundamentally, the president-elect’s view of how US policy should be managed within the broader international relations and global security arena seems to be shaped by his self-anointed image of being a proven ‘winner’ in the international corporate environment and his confidence that this background would be readily adaptable to managing an emerging and highly complicated world order.

Mira Rapp-Hooper, from the Center for a New American Security, has recently intimated that if Trump and his advisers are determined to stake out a US policy towards Asia in which its regional alliances and traditional approaches to order-building lose their traditional centrality, it may take months for the new administration to fashion an Asia–Pacific strategy. Or, as likely, ‘[g]iven Trump’s devotion to unpredictability, he might not craft such a strategy at all’. The incoming administration could ‘instead pick and choose from a neo-Jacksonian, unilateralist buffet, deciding what “America first” means as circumstances change.’

Those are valuable insights. But I’d argue that the new president will enjoy neither the luxury of time nor the unbridled freedom to choose from a menu of diverse and possibly disparate policy options, such as the above observation implies. Instead, he’ll be compelled by events and trends in the Asia–Pacific that are unfolding at breakneck speed, and by his own country’s resource constraints, to think and act quickly and coherently if acute regional instability is to be avoided.

Two key factors that will test the new administration’s ability to combine the old with the new in whatever Asia–Pacific policy positions it pursues are:

Failure to deal in good time with either of those emerging challenges could substantially erode the Trump administration’s foreign policy credibility and permanently undercut the US’s national security interests in the Asia–Pacific.

Over the longer term, it may well be the case that, confronted with resurgent US power, China, Russia or both may be inclined to pursue a ‘grand bargain’ with a ‘greater America’, Japan, India and the ASEAN members for long-term regional order-building. But that scenario seems a distant prospect in 2017, as Trump will apparently be preoccupied with repairing US domestic infrastructure and further resuscitating the US’s economic growth. Still, the outlook’s not entirely bleak. While Trump postulates an ‘America first’ posture, that hardly represents an ‘Asia last’ prescription. Above all else, Trump’s history is shaped by his reputation in the business world for hard but fluid bargaining to derive optimal results for interest-based objectives.

It might seem ludicrous to suggest that Chinese President Xi Jinping, the country’s most powerful leader since Mao, will be in danger in 2017. But looks can be deceiving, and his consolidation of power may not be as unassailable as it seems. The test will come next year, when the Chinese Communist Party holds its 19th National Congress to select a new team of leaders to serve under Xi.

To be sure, since becoming CCP General Secretary in November 2012, Xi has made great strides in establishing his own authority. With a sustained anti-corruption campaign, Xi has jailed more than 200 senior officials and generals—many of them members of rival factions. Unable to mount an effective counter-offensive, Xi’s rivals have watched him elevate his own supporters to key party posts.

But that might change at next year’s party congress. Though Xi is guaranteed a second term, he could struggle to overcome opposition to a series of personnel decisions that he is expected to make—or refuse to make.

In the post-Tiananmen era, the CCP has avoided destabilizing power struggles by designating the next president and prime minister years before power is actually handed over. In 1992, Deng Xiaoping picked Hu Jintao to take over in 2002. In 2007, the party’s top leaders agreed to anoint Xi as Hu’s successor, five years before the latter’s term expired.

But the system is informal, and thus unenforceable. So while the CCP aims to choose next year who will take over as president and prime minister in 2022, there is no guarantee that Xi will go along. After all, if a successor were not selected, Xi would have enormous flexibility in 2022, either to seek a third term or to appoint a loyalist to succeed him. If, by contrast, a successor is selected—an outcome that would be much better for the CCP’s reliability and legitimacy—Xi will become a lame duck.

Besides the expected showdown over the succession issue, Xi could also encounter resistance over two additional personnel matters.

The first is the size of the Politburo Standing Committee, the party’s top decision-making body, which currently has seven members, five of whom are expected to retire next year, having reached the informal age limit. If Xi replaced just three, creating a compact five-person committee packed with his own loyalists, he would achieve total dominance at the top. But it will not be an easy maneuver, as Xi’s rivals will fiercely oppose it.

The other issue is the fate of Wang Qishan, the head of the CCP’s discipline commission and the leader of Xi’s anti-corruption drive. If Wang retires next year, as party norms demand, Xi will lose his most dependable ally. But if Wang stays on, other members of the committee who have reached retirement age may also refuse to quit, effectively ending the age limit for CCP officials.

Given Xi’s record of subduing his foes almost effortlessly in recent years, it is tempting to bet that he will prevail in next year’s showdown. But there is a catch: the CCP Central Committee must sign off on proposed key personnel changes, and, despite the arrest of nine members, a substantial share of its 205 members remain loyal to Xi’s rivals. If they can act together and win the support of the CCP’s retired elders—people like former President Jiang Zemin, who continue to wield substantial influence—they might be able to sabotage Xi’s best-laid plans.

One political weapon Xi’s rivals can use is his record of policy failures since 2013, including a persistent economic slowdown, skyrocketing debt, slow progress on economic restructuring, and a real-estate bubble. Even the much-touted ‘one belt, one road’ initiative, which aims to connect Asia to Europe through a series of major infrastructure projects, could be a vulnerability for Xi, if CCP leaders decide it is too ambitious.

Resistance to Xi’s agenda is all the more likely, given that China’s economic woes seem set to intensify in the coming year. As the impact of credit-fueled stimulus fades, growth will decelerate further. An external shock, such as a trade war initiated by US President-elect Donald Trump, or even the expected increase in US interest rates, could cause the renminbi to depreciate, potentially precipitating a new round of capital flight. A crash in China’s red-hot real-estate market in first- and second-tier cities would intensify that capital flight, by putting immense pressure on a financial system that is already overburdened by bad loans.

It is impossible to know who will come out on top in next year’s power struggle in China. At the moment, Xi, who was just crowned the ‘core leader’ of the party, appears to have the edge. But it would be a mistake to write off his adversaries, for whom the stakes could not be higher: the 19th Party Congress is, after all, their last chance to preserve the post-Tiananmen order. That means that 2017 will be a dangerous year for Xi.