Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

America’s strategic deficit in the Asia–Pacific region was in plain sight during the recent Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore. Although North Korea was a key concern for all participants, many—especially those from Southeast Asia and Australia—found China’s strategic intention a more serious long-term challenge than North Korea’s nuclear weapons and missiles program. But this year, with the new Trump administration in Washington, they couldn’t count on the US to alleviate their anxiety.

In his keynote speech to the conference, Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull delivered a stark warning to China that it would face an opposing regional coalition should it ever want to impose its own version of the Monroe Doctrine in Asia. As my ANU colleague Professor Hugh White points out, Turnbull ‘has threatened China with Cold War-style containment.’ And ‘no regional leader—not even Japan’s bellicose PM Shinzo Abe—has ever gone this far before.’

The threat won’t go unnoticed in Beijing. But Chinese officials will do well to appreciate the stark but nonetheless subtle nature of the speech. The speech reflected Turnbull’s suspicion and even fear of China’s strategic intentions, but also gently conveyed his scepticism of the Trump administration’s strategic commitment to Asia when he declared: ‘In this brave new world we cannot rely on great powers to safeguard our interests.’

Thus, contrary to White’s interpretation that Turnbull ‘has sided with America against China in the starkest possible way,’ Turnbull’s speech in fact reflected mistrust of both China and the US. Of course, the mistrust of China is much deeper than that of the US, but the mere fact that an Australian leader has issued a clarion call to regional leaders about the need to protect their interests by their own efforts rather than relying on the great powers indicates an important shift in regional strategic trends.

Because of the unreliability of the American commitment, Australia—historically a staunch ally of the US—is now suggesting new hedging efforts by working with other countries to shape the region’s strategic future. China will have no illusions about Australia bandwagoning with it, but it has good reason to believe that, with hedging now a possibility for Australia, a crack has opened in the Australia–US alliance, owing in no small part to the unpredictability and unreliability of American foreign policy under the Trump administration.

Given the new regional anxiety about both China and the US, US Defense Secretary James Mattis’s affirmation of US strategic commitment to the region doesn’t surprise China. Mattis’s speech is so close to the American strategic mainstream that it’s almost indistinguishable from the Obama administration’s approach to Asia. It’s easy for Chinese observers to conclude that the Trump administration has still not figured out its own Asia strategy.

Chinese elites will also note two vexing dilemmas facing Mattis, now the leading strategist of the Trump administration. First, to what extent does his Asia policy represent Trump’s? Trump has so blithely undercut his high officials in key foreign policy matters—most recently over NATO and Qatar—that one wonders whether Mattis was really presenting only his preferred Asia policy, rather than the Trump administration’s settled one. If Trump’s transactional foreign policy is only about American self-interest, why would he bother about protecting a somewhat elusive ‘rules-based order’—a key part of America’s strategic commitment to the region? In any case, Trump never seems to have used concepts like the ‘rules-based order’ or ‘strategic commitment’.

Because of those uncertainties, Mattis faces the second major problem in his attempt at strategic reassurance: regional countries don’t buy it. The credibility of American commitment is now a major problem for the US position in Asia—a problem that skilful Chinese diplomacy may exploit.

But will China be able to successfully take advantage of America’s strategic deficit in the region? An opportunity has presented itself, but Chinese elites may also be taken aback by profound regional suspicions of China’s strategic intentions, represented most starkly in the Turnbull speech. It’s also a surprise that the South China Sea was still a key focus of this year’s conference despite the greater urgency of the North Korean problem. Since late last year, Beijing has been betting that the South China Sea has calmed down. The agreement on the framework text of a code of conduct for the South China Sea reached with 10 ASEAN countries on 18 May gives it more reason to believe so.

The stubbornness of the South China Sea problem underscores the dynamic strategic currents of the region. While widespread regional anxiety about the Trump administration presents a strategic opportunity for China, China must also try hard to alleviate regional concerns about its intentions, now largely focused on its strategy towards the South China Sea, especially island building. The US has a strategic deficit in the region; so does China. Reassurance is a strategic task for both countries.

Both China and the US are now sources of regional anxiety; their perceived unreliability is prompting regional countries to seek new strategic ‘self-help’ initiatives. For the US, such attempts signal the decline of its influence. For China, they suggest regional suspicions that, if not well managed, may lead to new forms of regional coalitions seeking to check Beijing’s rising influence even without the US. It will be a test of China’s diplomatic skills to manage those suspicions and navigate the emerging strategic trends.

It’s tricky. On one hand, moral superiority can lead dangerously to intolerance. But too much tolerance can open up strategic problems. That seems to be the crux of Mark Thomson’s proposition in his recent piece for The Strategist on the ‘wickedness of China’.

It’s tricky. On one hand, moral superiority can lead dangerously to intolerance. But too much tolerance can open up strategic problems. That seems to be the crux of Mark Thomson’s proposition in his recent piece for The Strategist on the ‘wickedness of China’.

Tolerance is a contextual quality. A theocracy allowing other some faiths, or an authoritarian state allowing some dissent, is simply giving what it can take back. A democratic state, with a culture deeply rooted in the mores and norms of a particular creed, regulating religious, cultural, or sexual diversity—whether that be the right to proselytise, use native dress or language, or follow sexual preference—embraces license, not liberty. No state has a claim to universally applicable institutions and values.

Genuine constitutional tolerance is to be found only in a state founded on the idea of neutral liberalism—neutral on what values and behaviours constitute a good life for individual citizens. As Rawls and Kant would have it, some basic individual rights override the government’s authority to act in the interest of the common good. That’s not the situation in Australia where the paucity of constitutional protection is transparent when contrasted with the individual protections in the US Constitution and Bill of Rights or the European Charter of Fundamental Rights.

States have a sovereign Westphalian right to determine their own system of governance. Were an ideal neutral liberal state to attempt to impose its own particular constitutional and institutional arrangements on other states it would fall into both a contradiction and an error. Liberal neutrality applied internationally should accept that the genuine and fundamental beliefs and cultural norms of many societies are resistant, if not antithetical or hostile, to the values that underpin neutral liberalism.

The error is to claim, as Mark does in his piece, that ‘there can be no legitimate rule without informed consent’; that can only be a subjective, value-laden moral opinion in the absence of an unchallengeable authority able to distinguish legitimacy from illegitimacy. The question of political legitimacy is complex and morally fraught.

Mark observes that Chinese citizens lack ‘the same rights and privileges’ available in the Australian political system. As these are relatively limited, presumably he means the values theoretically inherent in liberalism and democracy. Denial of those rights and privileges to its citizens by the illiberal and undemocratic Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is said to make it ‘wicked’—a moral term invoking something evil or morally wrong as opposed to something virtuous.

Apparently, acting in ‘economic self-interest’ is to be condemned as demonstrating that ‘our values have a price’. The obverse would be that Australian political values are somehow priceless, universal, unimpeachable and immutable. The argument I read in Mark’s piece is that the political constitution and the governmental institutions of Australia (and by implication those of other Westminster based or liberal democratic nations) are irrefutably superior because of their moral standing, and that any compromise on those values is therefore wrong.

Those institutions have ‘legitimacy’ because of those values whereas those of the CCP don’t. It’s an argument that the CCP can (and does) apply in reverse. And although liberalism and democracy are often linked, they aren’t the same thing. Many democracies—in Europe, and Russia, Turkey, and Iran—are more or less illiberal. Illiberal tendencies are on the rise in the US as well.

Apart from the paternalism and conceit of judging others by Australian values, there’s a far stronger strategic reason for exercising caution when criticising China’s domestic governance at present. That bigger issue is the abandonment of democracy promotion by the Trump administration.

The wisdom of American democracy promotion has been hotly contested since George W. Bush’s ‘Freedom Agenda’ in the wake of 9/11, under which the base causes of the terrorist attacks were assessed as the failures of the ‘political and economic doctrines’ tolerated in the Middle East and North Africa in the interests of national security.

By 2006, the best response to terrorism was seen as ‘the freedom and dignity that comes when human liberty is protected by effective democratic institutions’. That justification of democracy promotion found legislative backing in the ADVANCE Democracy Act of 2007, which declared democracy promotion ‘a fundamental component of United States foreign policy’. More recently, H.R. McMaster and Gary Cohn have explained that, in their view ‘the world is not a “global community” but an arena where nations, nongovernmental actors, and businesses engage and compete for advantage’ and in which America First will be pursued with the US’s ‘unmatched military, political, economic, cultural, and moral strength’.

Tillerson, McMaster and Cohn have outlined a Trump revolution in US foreign policy as radical as the Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan which led to NATO, a united Europe and containment of the Soviet Union, and laid the foundations for the liberal international order; the post-World War II consensus on security, trade, and international political norms and the institutions underpinning that order.

The Trump foreign policy is actually hostile to the most recognisable symbols of the liberal international world order—multilateral free trade, mutual defence and security agreements, and multinational institutions, including the supranational European Union. Tillerson has said that values have a minor place in this revolution; demonstrated by the administration’s praise for autocrats like Putin, Erdogan, al Sisi, Duterte, King Salman—and Xi Jinping.

Mark is right in noting that Australia is prudent, reticent and selective in criticising China and other nations for their failure to live up to Western standards. But describing that prudence as some kind of moral or strategic failing is neither good moral philosophy nor good strategic policy.

The naivety of offering a form of liberal moral universalism to guide strategic policy is problematic when all customary political and moral moorings are loosening—not just because of China, but because of the US, as well.

Over 20 years ago, at a conference in Sydney hosted by the Australian Navy, then-Indonesian Ambassador to Australia Sabam Siagian referred to the ‘Vasco Da Gama Epoch’. That was a reference to an expression originally coined by the noted Indian historian and diplomat, K.M Panikkar, in his book Asia and Western Dominance: A Survey of the Vasco da Gama Epoch of Asian History. It described the period between the arrival of Vasco da Gama in Calicut in Southern India in 1498 and the post-World War II period. This was the period when Indonesia and most of Asia fell under European economic and political domination until the Japanese ended the aura of European colonial invincibility in World War II. The post-war period saw former British, Dutch, French and American colonies and territories in Asia gain their independence.

Sabam Siagian, who died last year, was Indonesia’s Ambassador in Canberra from 1991 until 1995. However, he’s mainly remembered as the first Editor-in-Chief of The Jakarta Post, the English-language paper he helped to set up in Indonesia. He was a good communicator in English and, possessing an affable personality, was popular in Australia. Being forthright and outspoken, he wasn’t afraid of ‘rocking the boat’ of conventional wisdom. That was evident in his reference to the Vasco da Gama Epoch. Well ahead of his time, he wanted his Australian naval audience to contemplate a world in which Western powers, particularly the United States, didn’t enjoy the same power and influence in Asia as they had previously. Panikkar and his Vasco da Gama Epoch continues to have implications for Australia and our relations with Asia, particularly Southeast Asia.

K.M. Panikkar is highly revered by Indian strategic thinkers, but others also subscribe to his view of Asian history. Kishore Mahbubani, currently Dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy in Singapore, echoes similar ideas in his book The New Asian Hemisphere: The irresistible shift of global power to the East, in which he argues that many Western strategic thinkers remain trapped in the past, with an inability to understand the new world, and that Western power and influence isn’t the same as it was before. Pankaj Mishra is another eminent Asian writer who has picked up on insidious aspects of the Western presence in Asia, primarily in his book From the Ruins of Empire: The Revolt against the West and the Remaking of Asia.

Resentment of centuries of Western dominance is a major part of the strategic psyche of both India and China. Strategic thinking in India remains influenced by Panikkar’s writings. India is intent on becoming a pre-eminent power across the wider Indo-Pacific region. However, memories of the deployment of an American task force led by the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise to the Bay of Bengal at the height of the 1971 Indo-Pakistani War still linger in India’s strategic consciousness. That deployment was viewed by India as an act of American ‘gunboat diplomacy’ that India couldn’t deter at the time. That experience became part of India’s strategic justification for acquiring nuclear attack submarines and bolstering its aircraft carrier capability. In that context, the current détente between India and the United States could be short-term opportunism for India. Its vision of the regional future might well follow Panikkar by seeing no significant long-term role for the United States in Asia.

Similarly, repeated incursions by Western imperialist powers in Chinese history have left an indelible mark on Chinese strategic thinking, leading to an emphasis on national sovereignty and fears of encirclement. It’s unfortunate that many American strategic thinkers continue to show a lack of appreciation of China’s history, especially Western imperialism, and the wide extent of anti-Western sentiment in China.

The Trump presidency in the United States, and uncertainty about its future policies in East Asia, is now serving to strengthen regional views that the Vasco da Gama Epoch is near an end—more quickly perhaps than had previously been anticipated. President Trump’s recent visit to Europe has led to views that he’s ‘weakening the West’ . Those views can only support regional perceptions of declining Western influence.

Those perceptions may be under-appreciated in terms of their impact on regional strategic thinking and assessments of the future of the region. Philippine President Duterte’s stepping back from his country’s links with the United States and moving closer to China add further to the notion of the impending end of the Vasco da Gama Epoch. Similarly, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand, and even ASEAN itself as Southeast Asia’s principal regional institution, are all showing that they’re adjusting their strategic thinking to recognise the rise of China and the decline of American power and influence.

What does that mean for Australia? The late Coral Bell, one of Australia’s most eminent international relations scholars, addressed the implications for Australia of the end of the Vasco da Gama Epoch in a 2007 paper, concluding optimistically that ‘The United States will remain the paramount power of the society of states, only in a multipolar world instead of a unipolar or bipolar one’. Unfortunately events of the past decade, including the Global Financial Crisis and the faster than anticipated rise of China, mean some re-assessment of that conclusion is required.

The time will come when the Vasco da Gama Epoch does end and the West enjoys little power and influence in the region. When that happens, Australia won’t be able to lift up our anchor and sail across the Pacific to anchor off the coast of California. Malcolm Turnbull also acknowledged that Australia was locked into the region when, in his address to the recent Shangri-la Dialogue, quoted one time Australian Foreign Minister Paul Hasluck as saying that ‘Others can go…But we can’t go home because this is our home’. In the short-term, it might suit us to maintain support for the United States in the region, but we must also be realistic about the future when the United Sates is much less paramount in the region.

The shock of Donald Trump has prompted Australia to become shriller about China. Struck dumb by The Donald, Canberra can at least find its tongue about China.

The shock of Donald Trump has prompted Australia to become shriller about China. Struck dumb by The Donald, Canberra can at least find its tongue about China.

‘Shock and awe’ is probably too grandiose a term for the Trump effect in Canberra so far. ‘Shake and appal’ better catches the feeling.

Shake and appal drives Canberra to play nice with The Donald, and say nothing publicly that is critical of Trump. The discipline is dressed with great swathes of affection for the alliance. If you can’t say anything nice about the 45th president, please talk about all the wonderful things America has done in the past and could do in the future. It mightn’t be much of a template for policy, but it helps structure the speeches.

One knock-on effect of shake and appal has been the sharper language Australia is using about China. In quietly questioning Washington, Australia doesn’t want to be seen simultaneously moving towards Beijing. Instead, the approach is to question gently in one direction while pushing loudly in the other.

Strong words about China’s threat to the rules-based system can serve a dual purpose: speak to Beijing about the value of the system while implicitly pleading with the US not to abandon the system it has built and policed—and mightily profited from.

See the Trump-China dynamic in two Australian speeches in Singapore to the International Institute for Strategic Studies: The Fullerton Lecture in March by the Foreign Minister, Julie Bishop, (entitled ‘Change and Uncertainty in the Indo-Pacific’) and this month’s keynote to the Shangri-La Dialogue by the Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull.

First, the China shrillness. The scene was set by Bishop’s depiction of China ‘rising as an economic partner and geo-political and geo-strategic competitor with the US and other nations’.

The tone was even more striking when Bishop got to values and rules:

‘The importance of liberal values and institutions should not be underestimated or ignored. While non-democracies such as China can thrive when participating in the present system, an essential pillar of our preferred order is democratic community.’

From Bishop’s democratic backhander, Turnbull then put in the strategic boot, offering a ‘dark view’ of a ‘coercive’ China wanting ‘to impose a latter day Monroe Doctrine on this hemisphere in order to dominate the region, marginalising the role and contribution of other nations, in particular the US’.

My column from Singapore on Turnbull’s speech carried a big chunk of his China bashing. The strength/shrillness of Turnbull’s words on China made it eminently quotable. But the China stuff wasn’t what Asian and American delegates in the room were parsing after the speech. The interest was in Turnbull’s frantic semaphoring towards the US as he spoke of what Asia must build for itself—particularly the PM’s line that we can’t merely rely on the superpowers to protect our interests. And that the Oz alliance with the US isn’t a ‘straightjacket’. Australia couldn’t abrogate responsibility for its own destiny.

Turnbull’s Shangri-La speech is one of the most important foreign policy readouts of his leadership. It’s strong on how Asia has got to where it is now, firm on the things we don’t want to happen, and very strong on the importance of the US. It’s not so sure, though, on what to do next. And then there’s the silence on Trump, which a lot of people in the Shangri-La ballroom heard as the mute companion wail to the China shrillness. There was no criticism of Turnbull for any duality. Everyone is struggling.

Trump wants to dominate. If he can’t dominate, he disrupts. And amid the disruption, he reaches for a better deal. How to plan or predict with such a leader? It’s tough to talk values and rules to a man who works better at disruption and deals.

The shake and appal fears about what Trump might do—or fail to do—shape the silences and the gaps in Canberra’s Asia discussion. By contrast, the language on China rings louder. Look for Trumpian shapes in the spaces.

The coming Oz Foreign Policy White Paper is going to be a symphony, notable for the absence of Trump-et solos. There’ll be lots of stuff about the strength and vitality of the US alliance, along the lines of the AUSMIN talks with Defence Secretary Mattis and Secretary of State Tillerson in Sydney last week. The peak Oz-US ministerial had a ‘retro’ feel, and not just because it was held in the wonderful historic ambience of Government House. The ‘adults’ from Washington were visiting; but how much weight to put on their assurances about the great disruptor in the White House?

The questions the Americans directed at the Australian side could draw point from the 2017 Asia-Pacific Regional Security Assessment, released at Shangri-La by IISS. One of the 12 chapters on ‘key developments and trends’ considered ‘Australia’s uncertain regional security role’.

The key judgment offered on Oz was that it’d be logical to expect that a challenging regional order will cause Canberra to play a more active role, yet ‘doubts remain about its capacity and willingness to do so’. IISS judges the Turnbull government ‘cautious’ about any regional initiatives: ‘The considerable prevailing uncertainty over the depth of commitment of the new US administration to Asia-Pacific security may have contributed to Canberra’s strategic holding pattern.’

Expect more shrillness. The silences will be harder to maintain.

A joint investigation run by Four Corners and Fairfax into Chinese influence-buying in Australia aired on Monday night. It was a cracker, and if you missed it then we commend both the Four Corners episode (47 mins), as well as the interactive two-parter over at Fairfax: soft-power and hard-power. Concern about the degree to which Beijing wields influence in Australia also came up in James Clapper’s remarks and Q&A to the National Press Club on Wednesday—check out the transcript here.

Some quick bites on James Comey’s testimony. First up, two pieces from Benjamin Wittes of Lawfare—one on Comey’s written testimony, and one after the his appearance had wrapped up. Second, two efforts from The Atlantic—David Frum reckons Comey vanquished five lines of defence, and Amy Zegart on the era of ‘normalized deviance’. Third, some history for ya! And finally, Lawfare’s swelling list of Trump–Russia resources.

After a longread for your weekend? This personal reflection over at Buzzfeed looks at the Philippines’ political history and tries to reconcile the country’s devout Catholicism with the support shown for its barbarous and bellicose leader.

Let’s focus on two stellar research efforts this week. The first, which came out a few months ago but is worth re-upping, is from the CSIS Commission on Countering Violent Extremism. The report offers eight core policy recommendations to address CVE efforts predominantly in the US, but is also just as applicable internationally. The second is Nick Bisley’s fresh addition to ANU’s Centre of Gravity essay series, Integrated Asia: Australia’s Dangerous New Strategic Geography. Bisley dives into Asia’s shifting security order and considers where Australia should direct its efforts in an environment that’s less than sympathetic to Canberra’s interests.

And finally, at the time of writing, results from the UK’s general election are still coming in. But that doesn’t mean that we haven’t been able to enjoy some of the day’s spoils. We couldn’t go past some of the finer Tweets referencing ‘the naughtiest thing Theresa May has ever done,’ but nothing thus far has rivalled Lord Buckethead, a competitor for May’s constituency of Maidenhead. With a cool 249 votes under his…bucket…we’re confident the future holds great things for this budding politician. And finally, the hashtag #DogsatPollingStations has been trending on Twitter though unfortunately there has been no sign of a Dachshund named Colin. It’s great to see the pups exercising their democratic rights, voting for more treats and walks for good-boys nationwide.

Podcasts

For an authoritative voice on all things Trump, Comey and Russia, check out this timely special edition of Lawfare’s ‘Rational Security’ podcast (48 mins). As the testimony rolls onwards and upwards, you’re going to need the background…

It’s from a few weeks back, but if after the enlightening episode of 4 Corners this week you’re wondering about other parts of the world that China might be extending its economic tendrils, look no further than this fascinating podcast from the University of Melbourne. Over the 35 minute episode, Dr Lauren Johnston weighs up the pros and cons of Chinese investment in the Africa, and how it might impact on the Sino–African political relationship.

Video

If you haven’t come across the CrashCourse YouTube channel yet, allow us to introduce you. Offering short lessons on subjects from sociology to film history to mythology, with each episode you’ll find yourself becoming an expert on topics you hadn’t considered before. While we at The Strategist find it hard to go past the World History series, this week’s Computer Science episode (13 mins) is dedicated to Alan Turing, whose work ranged from breaking Nazi codes in WWII, to what we now call Artificial Intelligence.

Events

Sydney: The Lowy Institute’s Owen Harries Lecture is set to be delivered early next week by Jake Sullivan, a former senior advisor to Hillary Clinton. And if you can’t get along, Jake is hitting the road to pop up in Melbourne and Canberra on the 15th and 19th respectively.

Canberra: Middle East heavyweight and former policy advisor to the US Forces in Iraq Emma Sky will be stopping into the nation’s capital to give her thoughts on the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and whether or not the botched war has contributed to the end of Pax Americana. Mark your calendars for 21 June, and register here.

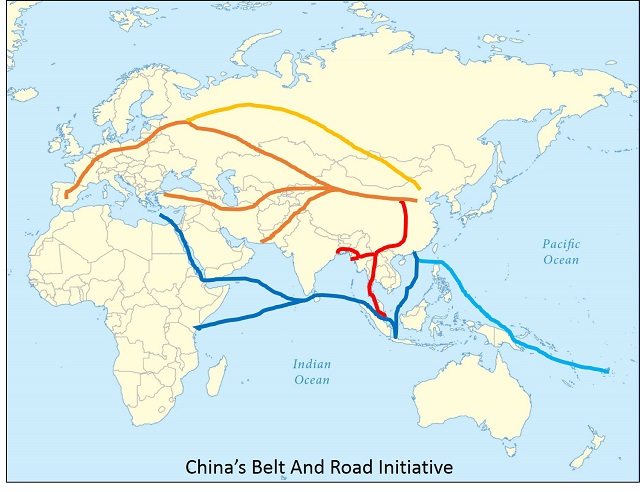

President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has caused much discussion about China’s vision for engaging the world economically. In many ways, it can bring ‘win–win’ opportunities for China’s economic partners, but there’s also potential for less desirable, unintended consequences arising from this ambitious plan.

China’s rise has seen its footprint of personnel and commercial interests overseas expand at a bewildering pace over the past two decades. Many Chinese continue to leave their shores in search of wealth and resources, either as individuals or as members of large commercial organisations. Chinese communities overseas, estimated at 35 million nine years ago, have become valuable assets in connecting China to the outside world, but they are also a potential liability. While this growing presence and influence can develop strategic interests beyond the original design, a growing subset of them are increasingly at risk from natural disasters, breakdowns of civil order, acts of terrorism, and exposure to war zones.

This growth in overseas Chinese communities has been accompanied by the continued expansion of military capability to protect China’s interests abroad and the development of a substantial middle class that expects the Communist Party to protect the Chinese diaspora. Such a development of risk accompanied by the means and expectation to address it generates a perceived obligation to act in self-defence overseas.

China’s first declared overseas military base, in the port of Obock in Djibouti, is an example of what can follow the development of commercial interests. The base will support counter-piracy patrols in the Gulf of Aden, enable China’s deployment of combat troops on peacekeeping operations on the African continent, and provide protection for Chinese oil imports from the Middle East at a strategic node in the BRI.

This combination of trends in growth, interests, capability and obligation is demonstrated by the recent phenomenon of Chinese evacuation operations. Referred to in China as ‘overseas citizen protection’, they have been conducted since 2006. At the turn of the century, China didn’t have the capacity, or policy, to conduct evacuation operations, and seemed content to ask other countries to evacuate its citizens.

In 2004, when 14 Chinese workers were killed in Afghanistan and Pakistan, the domestic reaction caused China to review its overseas citizen protection system, acknowledging that large numbers of Chinese were living in high-risk environments overseas. China started to conduct small evacuations using civilian means to extract citizens from Solomon Islands, Timor Leste, Tonga and Lebanon in 2006, Chad and Thailand in 2008, and Haiti and Kyrgyzstan in 2010.

The largest evacuations occurred in 2011, during the Arab Spring uprisings, when China retrieved 1,800 citizens from Egypt, 2,000 from Syria and 35,860 from Libya, along with 9,000 from Japan after the Tohoku earthquake. The 48,000 Chinese evacuated in 2011 were more than five times the total number evacuated between 1980 and 2010.

This was the first such operation to significantly involve the PLA in more than decision-making and interagency coordination in Beijing, providing surveillance, deterrence, escort and evacuation by air in the operation itself.

More recently, between 30 March and 2 April 2015, a Chinese flotilla of three PLAN naval vessels was diverted from its counter-piracy mission in the Gulf of Aden to evacuate Chinese citizens from the port of Aden in Yemen. Some 563 Chinese citizens and 233 foreign citizens of 13 other nationalities were evacuated by the PLAN to Djibouti.

This was a significant development, as it was performed exclusively with military assets and was the first time the PLAN had evacuated citizens of other countries.

According to one analysis, the requirement to protect nationals abroad is much more likely to cause Chinese foreign policy to become interventionist than the protection of energy interests, largely because of public and government attention. There’s a risk that as China acts to protect its interests in areas perceived as of lesser strategic priority, such as the Southwest Pacific, its actions will generate unintended second and third order effects, with undesirable strategic consequences. This possibility has been referred to as ‘accidental friction’.

There’s evidence of an anti-Chinese mindset in Melanesian societies, associated with a belief that the ‘new Chinese’ are taking away local jobs. This perception is reinforced by negative media coverage of Chinese commercial ventures in the Pacific. Such tensions occasionally boil over into anti-Chinese violence, such as that seen in Solomon Islands and Tonga in 2006 and PNG in 2009. However, public and government opinion in China is not always sympathetic to the Chinese who are targeted in these riots.

Given the potential for anti-Chinese riots in the South Pacific, the requirement for Chinese ‘overseas citizen protection’ may become a reality in Melanesia in the near future.

If Australian and Chinese military contingents were to find themselves involved in an evacuation operation in a difficult or threatening environment, and without prior preparation, the consequences may be undesirable. A lack of understanding of each other’s techniques, control measures and rules of engagement could be quite dangerous to all involved. Such unintended consequences could be mitigated by engaging, understanding and cooperating well before this happens.

‘In this brave new world we cannot rely on great powers to safeguard our interests.’

Malcolm Turnbull, Singapore, June 2, 2017.

Australia’s Prime Minister has given a big Asia speech that attacked China directly while aiming indirect attacks at Donald Trump’s world view.

Malcolm Turnbull didn’t say one critical word about Trump. Instead, Turnbull dumped implicit acid on US policies, while only twice mentioning Trump (relatively positively) by name.

The problem for Turnbull’s Singapore oration was that all big foreign policy speeches are hostage to the times and the troubles. And Turnbull’s Asia moment was ambushed by Trump’s context.

Turnbull opened a Shangri-La security conference that finds itself in an unusual place—more worried about US intentions and leadership than about China. Strange days, indeed, when the reigning hegemon is more unpredictable than the rising power.

The times-and-troubles frame for the PM is a US President who sees international relations as a version of The Hunger Games. Trump has promised a foreign policy of ‘Principled Realism rooted in common values, shared interests, and common sense’. But the Hobbesian interpretation of that realism in the op-ed by Trump’s national security adviser and chief economic aide is ‘a clear-eyed outlook that the world is not a “global community” but an arena where nations, nongovernmental actors and businesses engage and compete for advantage’. So no community, just a crude view of power. And The Donald doesn’t believe in shackling US power to ‘global community’ constructs like the Paris Climate Change Agreement.

The tactic of thumping Trump without mentioning Trump was most on show in the PM’s one paragraph registering disappointment at the US withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Paris pact:

‘Some have been concerned the withdrawal from the TPP and now from the Paris Climate Change Agreement herald a US withdrawal from global leadership. While these decisions are disappointing, we should take care not to rush to interpret an intent to engage on different terms as one not to engage at all.’

Turnbull had his Angela Merkel moment with the thought that Australia and Asia can’t depend on China and the US to fix our problems. Following the Merkel example, Turnbull didn’t actually name the troublesome giants:

‘In this brave new world we cannot rely on great powers to safeguard our interests. We have to take responsibility for our own security and prosperity while recognising we are stronger when sharing the burden of collective leadership with trusted partners and friends. The gathering clouds of uncertainty and instability are signals for all of us to play more active roles in protecting and shaping the future of this region.’

Contemplate the moment when an Oz Liberal PM couldn’t quite rely on our great and powerful friend. Malcolm Turnbull’s alliance love comes with caveats:

‘Our Alliance with the United States reflects a deep alignment of interests and values but it has never been a straightjacket for Australian policy-making. It has never prevented us from vigorously advancing our own interests. And it certainly does not abrogate our responsibility for our own destiny.’

The public Oz position on Trump still reads: ‘No problem here. Nothing to see. Move along.’

The Defence Minister, Marise Payne, presented a fine example of that genre in Singapore on Friday morning after the ministerial meeting of the Five Power Defence Arrangements (FPDA = Singapore, Malaysia, Australia, New Zealand and Britain). At the presser, the first question was whether FPDA is being enhanced as an alternative to the US security role in Asia.

Senator Payne replied by saying that in Australian Rules footy, the question would be described as a ‘drop punt’. I later tackled the Defence Minister with the charge that this was a nonsensical footy analogy that worked only because Asia hacks know nothing about Oz football. To which, Marise Payne replied with a laugh: ‘That’s exactly why I used it’.

My translation: when asked about Trump and Asia, resort to opaque football metaphors (the Oz version of ancient Chinese proverbs) and hold to a public script that doesn’t kick Trump. The tough talking is to be done in private.

Before his Shangri-La speech, Turnbull had a bilateral with the US Defense Secretary, James Mattis. There’ll be another chance on Monday, when Mattis and Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, are in Sydney for the annual AUSMIN talks.

Turnbull’s cautious/hopeful handling of Trump contrasts with his robust language about the ‘dark view’ of a ‘coercive China’ seeking domination. He challenged China to strengthen the regional order as it reaches for greater strategic influence:

‘Some fear that China will seek to impose a latter day Monroe Doctrine on this hemisphere in order to dominate the region, marginalising the role and contribution of other nations, in particular the United States. Such a dark view of our future would see China isolating those who stand in opposition to, or are not aligned with, its interests while using its economic largesse to reward those toeing the line… A coercive China would find its neighbours resenting demands they cede their autonomy and strategic space, and look to counterweight Beijing’s power by bolstering alliances and partnerships, between themselves and especially with the United States.’

In last year’s Defence White Paper, Australia was obsessed by the need for rules and order: the word ‘rules’ was used 64 times—48 of those in the formulation ‘rules-based global order’. Then, Australia used the ‘rules’ injunction as code for fears about China. Now the call for rules and order is directed as much at the US as China.

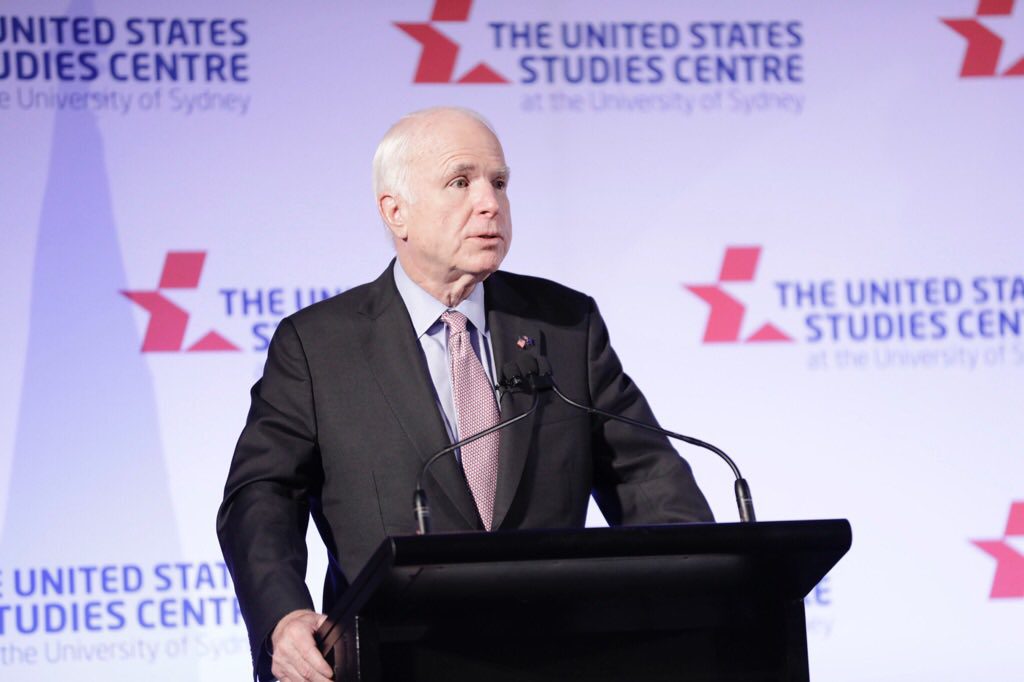

John McCain’s speech in Sydney this week offered an emotionally-appealing restatement of the orthodox, establishment view of Australia’s alliance with America. In doing so the veteran Republican senator showed quite plainly why that view is inadequate as a basis for our thinking about the future of the alliance and Australia’s place in Asia over coming decades. We’d be wise to pay more attention to Angela Markel’s remarks in Bavaria last weekend.

At the heart of McCain’s speech was a simple and familiar argument. It is that America and Australia are allies not because we share interests and objectives—what he called ‘narrow materialism’—but because we share history and values. He spoke eloquently about our shared history, recalling his family’s long connections with Australia as a military partner. And he spoke very directly about the role of shared values in underpinning and motivating the alliance.

‘Why are we allies?’, he asked, and offered this answer: ‘The animating purpose of our alliance is that we are free societies…who put our faith in the rule of law, and who believe that our destinies are inseparable from the character of the broader world order.’

He spoke of ‘the rights and independence of the weak’, the right ‘to sail the seas, and fly the skies, and engage in commerce freely’, and the need to resist those ‘bent on injustice, and aggression, and conquest’.

‘These are values that time does not diminish,’ McCain concluded. ‘These are ideas that truly are worth the fighting for. This is why we are allies—and why we must remain so.’

One can see the appeal of this. History and values are, by definition, enduring and unchangeable—‘time does not diminish’—so those who passionately want the alliance to endure naturally give weight to them rather than to the shifting sands of interests and objectives.

But reality must be allowed to intrude, and the reality is that alliances only endure when they demonstrably serve clear contemporary national objectives on both sides, and when the costs they impose are worth the benefits they bestow.

Those who really care about the alliance and its future should look beyond the warm generalities of history and values and examine the cold facts. How far do our strategic interests and objectives converge with America’s in the decades to come?

This isn’t an abstract question. Each country needs to ask what exactly is—in McCain’s words—‘worth fighting for’ in Asia. Talk of values is cheap, but fighting for them against an adversary as powerful as China, as McCain seems to be suggesting, is not. Over the past few years it has become less and less clear that America is willing to accept the costs and risks of defending the regional order from China’s challenge.

That was so even before Americans elected Donald Trump, and it is much plainer now. McCain urged us to ignore Trump as an anomaly. He wants us to believe, as he does, that the real America remains committed to upholding its global leadership at any cost. But all the evidence from last year’s election—on both sides of US politics—points the other way.

Trump may be unprecedented, but he isn’t an anomaly. His election is the clear consequence of long-standing trends in US politics. And while Trump might not last long, the trends and attitudes he represents, including his ‘America First’ isolationism, will persist.

And why not? Traditionalists like McCain talk tough, but they have no credible ideas about how America should perpetuate its leadership in today’s world. In particular, they have no idea what to do about China. McCain’s ‘Asia-Pacific Stability Initiative’ is little more than a rebadged ‘Pivot’, and would fail just as the Pivot did, because it doesn’t commit anything remotely approaching the massive resources required to meet China’s challenge.

There’s a reason for that. No one believes that Americans today would support a policy which commits the resources required. That means we would be very unwise to expect that America will sustain its leadership in Asia, and if it doesn’t, then—history and values notwithstanding—it won’t need Australia as an ally.

Nor is Australia’s commitment to supporting America nearly as clear-cut as our alliance rhetoric suggests. For all our tough talk, Australian governments haven’t been willing to support America in pushing back against China in any way that might damage our standing in Beijing. And how much weight would our shared history and values have if we ever do have to choose whether to support America in a war with China?

We aren’t alone in facing these questions. Around the world America and its allies are struggling to understand what their alliances mean in a changed world in which America’s relative power and resolve are much depleted, and it confronts major challenges in several key regions.

This is the reality that Angela Merkel has acknowledged so frankly. It isn’t just about Donald Trump. Under any president, how credible is it that America would risk a nuclear war with Russia to save Estonia from Vladimir Putin? Or Poland, come to that?

The difference is that Merkel has the courage and candor to acknowledge the problem, which is the essential first step towards doing something about it. Senator McCain doesn’t, and neither do we.

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s tenure has been marked by high ambition. His vision—the ‘Chinese dream’—is to make China the world’s leading power by 2049, the centenary of communist rule. But Xi may be biting off more than he can chew.

A critical element of Xi’s strategy to realize the Chinese dream is the ‘one belt, one road’ (OBOR) initiative, whereby China will invest in infrastructure projects abroad, with the goal of bringing countries from Central Asia to Europe firmly into China’s orbit. When Xi calls it ‘the project of the century,’ he may not be exaggerating.

In terms of scale or scope, OBOR has no parallel in modern history. It is more than 12 times the size of the Marshall Plan, America’s post-World War II initiative to aid the reconstruction of Western Europe’s devastated economies. Even if China cannot implement its entire plan, OBOR will have a significant and lasting impact.

Of course, OBOR is not the only challenge Xi has mounted against an aging Western-dominated international order. He has also spearheaded the creation of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, and turned to China’s advantage the two institutions associated with the BRICS grouping of emerging economies (the Shanghai-based New Development Bank and the $100 billion Contingent Reserve Arrangement). At the same time, he has asserted Chinese territorial claims in the South China Sea more aggressively, while seeking to project Chinese power in the western Pacific.

But OBOR takes China’s ambitions a large step further. With it, Xi is attempting to remake globalization on China’s terms, by creating new markets for Chinese firms, which face a growth slowdown and overcapacity at home.

With the recently concluded OBOR summit in Beijing having drawn 29 of the more than 100 invited heads of state or government, Xi is now in a strong position to pursue his vision. But before he does, he will seek to emerge from the National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party later this year as the country’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong.

Since taking power in 2012, Xi has increasingly centralized power, while tightening censorship and using anti-corruption probes to take down political enemies. Last October, the CCP bestowed on him the title of ‘core’ leader.

Yet Xi has set his sights much higher: he aspires to become modern China’s most transformative leader. Just as Mao helped to create a reunified and independent China, and Deng Xiaoping launched China’s ‘reform and opening up,’ Xi wants to make China the central player in the global economy and the international order.

So, repeating a mantra of connectivity, China dangles low-interest loans in front of countries in urgent need of infrastructure, thereby pulling those countries into its economic and security sphere. China stunned the world by buying the Greek port of Piraeus for $420 million. From there to the Seychelles, Djibouti, and Pakistan, port projects that China insisted were purely commercial have acquired military dimensions.

But Xi’s ambition may be blinding him to the dangers of his approach. Given China’s insistence on government-to-government deals on projects and loans, the risks to lenders and borrowers have continued to grow. Concessionary financing may help China’s state-owned companies bag huge overseas contracts; but, by spawning new asset-quality risks, it also exacerbates the challenges faced by the Chinese banking system.

The risk of non-performing loans at state-owned banks is already clouding China’s future economic prospects. Since reaching a peak of $4 trillion in 2014, the country’s foreign-exchange reserves have fallen by about a quarter. The ratings agency Fitch has warned that many OBOR projects—most of which are being pursued in vulnerable countries with speculative-grade credit ratings—face high execution risks, and could prove unprofitable.

Xi’s approach is not helping China’s international reputation, either. OBOR projects lack transparency and entail no commitment to social or environmental sustainability. They are increasingly viewed as advancing China’s interests—including access to key commodities or strategic maritime and overland passages—at the expense of others.

In a sense, OBOR seems to represent the dawn of a new colonial era—the twenty-first-century equivalent of the East India Company, which paved the way for British imperialism in the East. But, if China is building an empire, it seems already to have succumbed to what the historian Paul Kennedy famously called ‘imperial overstretch.’

And, indeed, countries are already pushing back. Sri Lanka, despite having slipped into debt servitude to China, recently turned away a Chinese submarine attempting to dock at the Chinese-owned Colombo container terminal. And popular opposition to a 15,000-acre industrial zone in the country has held up China’s move to purchase an 80% stake in the loss-making Hambantota port that it built nearby.

Shi Yinhong, an academic who serves as a counselor to China’s government, the State Council, has warned of the growing risk of Chinese strategic overreach. And he is already being proved right. Xi has gotten so caught up in his aggressive foreign policy that he has undermined his own diplomatic aspirations, failing to recognize that brute force is no substitute for leadership. In the process, he has stretched China’s resources at a time when the economy is already struggling and a shrinking working-age population presages long-term stagnation.

According to a Chinese proverb, ‘To feed the ambition in your heart is like carrying a tiger under your arm.’ The further Xi carries OBOR, the more likely it is to bite him.

Beijing’s great celebration of the Belt and Road Initiative was a lavish display of China’s promise and power. All those nations paying court to Xi Jinping’s celebratory circus confront the conflicting emotions captured by a fine journalistic phrase-maker who won a day job as Australia’s Prime Minister. Asked by Angela Merkel in 2014 what was driving Oz China policy, Tony Abbott got it into one vivid phrase: ‘fear and greed’.

Abbott’s zinger resonates across Asia as it does in Australia. Power shifts riding on huge wealth effects naturally produce avarice and apprehension. ‘Power’ can be both a plural or singular noun; and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is dollar power dancing with soft power while holding hands with hard power.

Just as the Beijing Olympics was a moment of greatness, Beijing’s BRI bonanza is another magnificently-staged moment: China reaches out to 60 countries with infrastructure, trade, finance—and ambition. Exporting China’s model will be extremely difficult. Lots won’t work. Plenty of cash will gurgle away. Factor in many failures as China tries to build big in foreign climes.

Yet if Beijing delivers only half of its BRI promises, that’s a lot of power created, an even bigger leadership role for China, and a greatly enhanced web of bilateral and regional relationships.

Xi’s dream is of the dominant Asian power cementing its dominance with cement. The world’s second biggest economy in dollar terms—and since 2014 the world’s biggest economy in purchasing power parity—is rolling out mountains of dollars. While Donald Trump looks inward to make America great again, Xi reaches out to make China great again on the world stage.

Watching it all in Beijing, Rowan Callick saw a party with lots of power dimensions:

‘China under Xi has moved into the space left by Washington, as a can-do, big-picture, global-scale economic mover and shaker—with geopolitical strings attached.

No one can afford to ignore or underestimate China, the only country with the economic grunt to carry this off. The timing for BRI is fortuitous and impeccable.’

Australia’s former ambassador to China, Geoff Raby, says Beijing has three BRI imperatives:

What China has already built in Asia this century is the model for what it wants to replicate on a larger scale. And what China has already done shows the pitfalls. Beijing’s major infrastructure build in Sri Lanka was based on President Mahinda Rajapaksa and his political machine. Rajapaksa’s election loss in 2015 was partly about Sri Lankans rejecting a Chinese embrace. The same story can be read into Myanmar’s 2011 decision to walk away from a giant Chinese dam project; Myanmar’s regime turned towards democracy as it turned away from Chinese dominance.

Evelyn Goh’s depiction of China’s rising influence in developing Asia shows a patron that doesn’t get all it wants from its supposed clients. In contrast to the US’s security-focussed approach, Goh sees China offering Asia an economic and development partnership with these characteristics:

Goh describes Chinese blind spots that’ll be important in how BRI plays out. Beijing, she writes, downplays the autonomy of its neighbours/clients, seeing any deviation from Beijing’s vision as the dark machinations of other great powers. China overlooks the contradictions between its ‘benign modes of influence’ and its coercive behaviour in the South China Sea.

Chinese policymakers see the toughening stances of rival claimants in the South China Sea as being caused by the US, Goh writes:

‘rather than as nationalist responses to Chinese assertiveness in bilateral conflicts. Chinese analysts, policymakers and public opinion are experiencing a dissonance between their growing material power and their perceived lagging status, influence and effectiveness in the international realm. It is by no means clear that Beijing is easily able to win over developing countries to which it can promise quick credit and cheap infrastructure.’

A lot of those offered BRI largesse will take the money now and worry about Chinese influence later. Australia sits on the fence, attending the Beijing jamboree but not embracing the Initiative.

Canberra confronts the dilemma it struggled with when China created the Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank. On AIIB, Australia pushed aside fear and embraced greed. Or, more politely, ambition trumped apprehension. BRI asks Australia the AIIB question on a bigger scale. The answer Canberra gives will be an important readout on how Australia’s sees the greed-and-fear balance involved in an ever-greater China.