Pakistan’s release of LeT head: bad idea, wrong signals

The decision to release Hafez Muhammad Saeed—the founder and leader of Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), a US- and UN-designated terrorist organisation—by a court in Lahore last week will be poorly received by Pakistan’s external interlocutors, particularly India and the US, but also China.

India has accused Saeed of being the mastermind behind the Mumbai terror attack in November 2008 that killed 166 people. His release will certainly do nothing to ease Pakistan–Indian bilateral relations. If anything, it will aggravate an already difficult situation, especially following the recent unveiling of President Donald Trump’s much-heralded new South Asia policy.

The Pakistan government had argued that Saeed’s nine-month house arrest should be extended again because he remained a threat to public safety and his release would attract financial sanctions against the country and lead to a halt in foreign funding for Pakistan’s failure to move against terrorism financing. The court rejected the government’s argument on the grounds of insufficient evidence.

The Indian government was ‘outraged’ by the decision. The foreign ministry stated that Saeed’s release was an attempt by ‘the Pakistani system to mainstream proscribed terrorists’. Privately, Delhi probably wasn’t too surprised. Saeed had been arrested several times on criminal and terrorism charges since the 2008 Mumbai attack, but each time his house arrest had been lifted. Delhi has repeatedly demanded that Saeed be handed over for trial in India.

Washington wouldn’t have been pleased either, though American annoyance will probably be limited. In the lead-up to Saeed’s release, the US State Department had expressed its displeasure. But since then the White House has been very quiet. While the Thanksgiving long weekend may have something to do with it, I suspect it’s mainly because the Trump administration wants to ease back on its anti-Pakistan rhetoric.

In his speech in August in which he revealed his South Asian policy, Trump didn’t beat around the bush in effectively saying that Pakistan was playing both sides when it came to counterterrorism. He demanded that Pakistan stop this immediately and ‘demonstrate its commitment to civilization, order, and to peace’. Trump also encouraged a greater role for India in Afghanistan, asking it to help the US more. That would have been like a red rag to a bull. And, indeed, Islamabad went ballistic—quite understandably so.

The White House heard Pakistan’s reaction loud and clear. Importantly, the Trump administration knows that Pakistan is a critical and essential player in trying to find a peaceful solution to Afghanistan. Washington simply can’t afford to alienate Islamabad. However, the administration also knows that its leverage over Pakistan is very limited. So it went into damage control, deciding that the Afghan angle of its South Asian policy was more important than the Indian one. Or, put differently, the White House decided that perhaps it had gone too far in its pro-India rhetoric.

So, while the LeT has been classified as a foreign terrorist organisation by the US government since 2014 and there’s a US State Department offer of US$10 million for information leading to Saeed’s arrest, the White House appears to have decided to downplay these issues. For example, when the US shared its list of known terrorists with Pakistan during Secretary of State Rex Tillerson’s visit in October, Saeed wasn’t on it.

But most importantly, the Department of Defense put a lot of pressure on key congressional committees to drop a provision linking financial aid to Pakistan with Islamabad taking action against the LeT. That was the first time the Senate had included the LeT—along with the Haqqani Network—as a condition for Pakistan to receive US$350 million in coalition support for its role in the war in Afghanistan. So not including the LeT was a significant victory for Pakistan.

Further confirming Washington’s desire to patch things up with Islamabad, General John Nicholson, the commander of US and NATO forces in Afghanistan, offered to take action against Taliban fighters involved in cross-border raids from the Afghan side of the border. Pakistan accepted the offer. The timing of Nicholson’s gesture is crucial: US Defense Secretary James Mattis is expected in Islamabad on 3 December to discuss Pakistan’s support for Washington’s new South Asia policy, specifically with regard to Afghanistan. Whether all of those overtures will be enough to put the US–Pakistan relationship back on track is another matter.

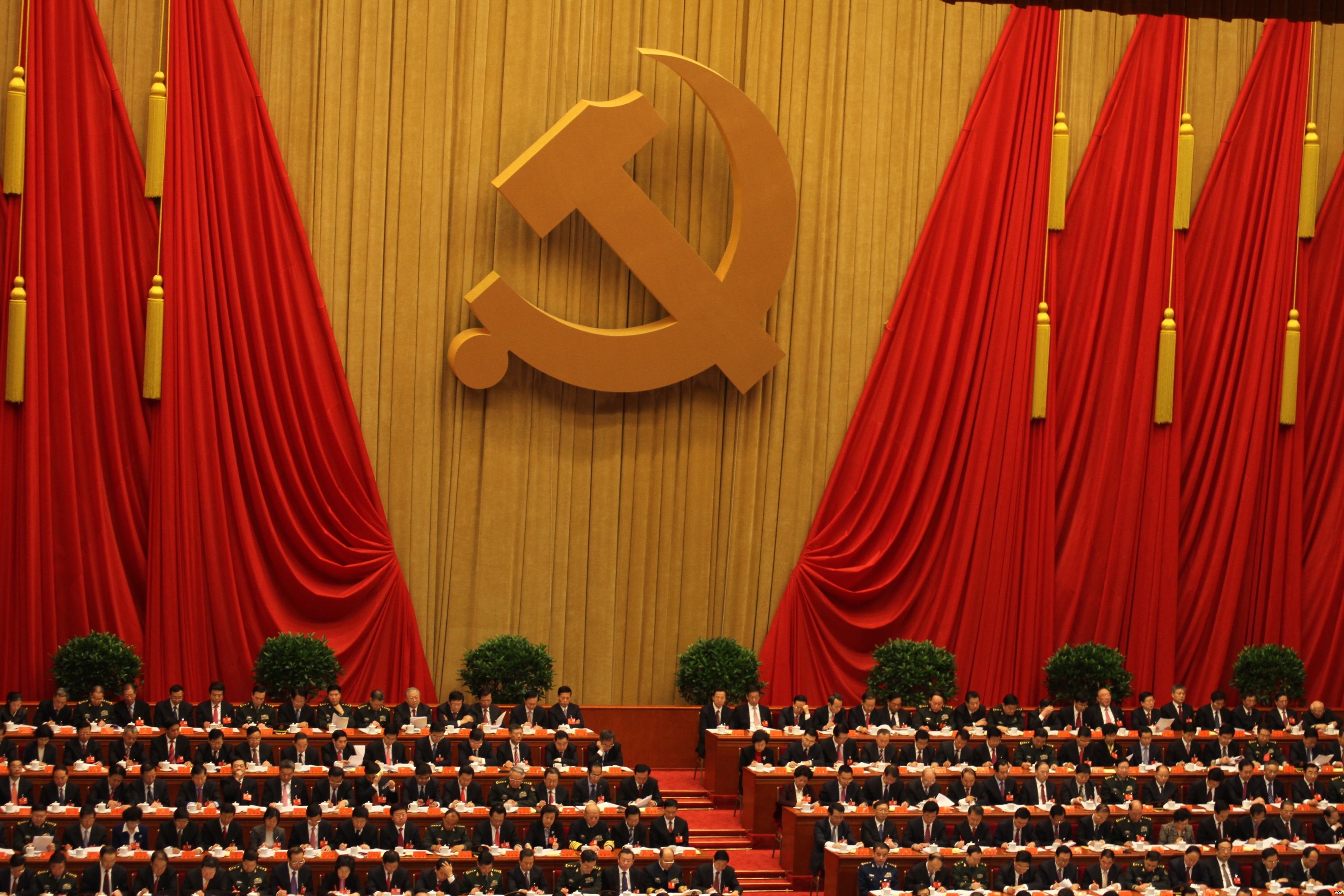

China, Pakistan’s closest ally, is the other regional player that won’t be pleased about the release of Saeed. And although Beijing has regularly used its veto at the UN to prevent Saeed from being classified as a terrorist, it knows that his release will create further friction between India and Pakistan. Such a development could threaten the peaceful regional environment that Beijing wants for the implementation of the US$50 billion China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) project. China has a lot of prestige invested in CPEC, a cornerstone of its One Belt, One Road grand plan for Asia and beyond. The release of Saeed, a man whose firebrand reputation has been built on wanting to drive Indian forces out of Kashmir, therefore comes at a delicate time, given that some of the CPEC projects will be going through the disputed border region with India.

So all in all, Saeed’s release will complicate Pakistan’s relations with friends and foes in the neighbourhood. And the situation may get worse if Saeed decides to enter politics in the lead-up to the parliamentary elections next year. Saeed is a troublemaker with a strong following who shouldn’t be dismissed lightly. He also knows that he’s virtually untouchable, having been supported by the generals tacitly, if not implicitly, for the past 30 years. And, notwithstanding its statements, the Pakistan Army isn’t about to dump him. His LeT fighters play a too-important role in the never-ending Indo-Pakistan confrontation. So expect more trouble ahead.