Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

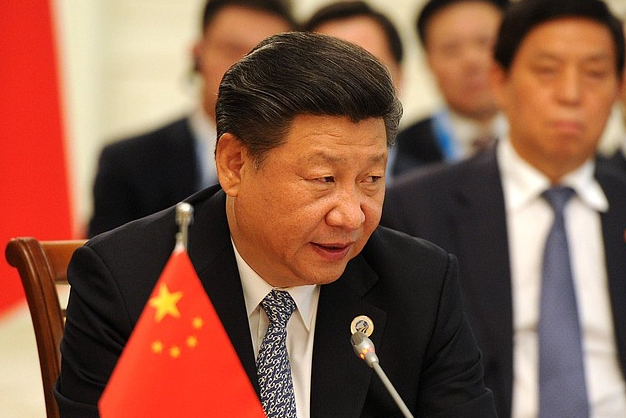

While the 13th National People’s Congress in China earlier this month grabbed international attention—particularly the constitutional amendment eliminating presidential term limits—other important developments in cross-Straits relations also took place.

Premier Li Keqiang vowed that there’s no tolerance for Taiwanese independence. He also promised ‘friendship’ and an expanding relationship across the Taiwan Straits in which Taiwan would play a part in the ‘nation’s’—that is, Beijing’s—rejuvenation efforts. In other words, independence is out of the question, but there’s an option for a beautiful and prosperous future together.

No wonder US President Donald Trump’s signing last week of the Taiwan Travel Act stirred Beijing’s anger and invited promises of retaliation and the ‘punishment of history’. The act allows unrestricted two-way travel between the US and Taiwan for American and Taiwanese officials.

Chinese state media reminds everyone that article 8 of China’s 2005 anti-secession law states that Beijing will pursue ‘non-peaceful means and other necessary measures’ to prevent Taiwan’s secession. China has been consistently trying to limit Taiwan’s international space. For that reason, opening a channel for official exchanges with the US is an unwanted development.

Late last year, a Chinese diplomat in Washington DC, Li Kexin, warned that the day a US warship visits Taiwan would be the day that the People’s Liberation Army would reunite Taiwan with China by force. Since Xi Jinping became president, Beijing has pushed a more assertive regional strategy that includes further encircling Taiwan.

In recent years, the PRC’s project to limit Taiwan’s diplomatic space has accelerated. For example, Panama—a Taiwanese diplomatic partner since 1912—cut ties with Taiwan last year. As detrimental as the incident was for Taipei, by no means was it exceptional.

In 1969 there were 71 countries that recognised Taiwan and 48 that recognised the People’s Republic of China. Currently, Taiwan has 20 diplomatic allies, whereas the PRC has 175.

Not only have Taiwan’s bilateral relations suffered, but also its ability to participate in or observe multilateral fora. Beijing is busy vetoing Taiwanese delegates’ participation in inter-governmental organisations and other gatherings where Taiwan has been an observer.

Recently, INTERPOL and the International Civil Aviation Organization refused Taipei’s request to attend their general assemblies. Even in the international business and industry worlds, Taiwan’s presence is increasingly problematic. The Kimberly Process—a gathering of the diamond industry—met in May 2017 in Australia. The Chinese delegation forced the exclusion of the Taiwanese team.

Beijing’s goal is to eliminate international recognition that Taiwan is an independent actor with the right to have its own representation. Instead, the PRC wants Taiwan to be treated by the international community as a purely ‘domestic matter’.

The Taiwan Travel Act complicates Beijing’s plan. The US is determined to support Taiwan’s participation in the international community. Bilateral relations have gained a new spin since Donald Trump assumed the presidency, starting with him accepting a congratulatory phone call from Taiwanese President Tsai Yin-wen.

For a while, it was thought that this represented a sharp policy change in cross-Straits relations and an early signal that Trump would be more assertive in the US relationship with China. However, President Trump quickly reaffirmed his commitment to the One China policy.

His polar swings between embracing and confronting the PRC have now become his ‘signature’ policy—to uncertain effect. In mid-2017, for example, Trump approved a US$1.4 billion arms sale to Taiwan. Predictably that angered Beijing.

‘Displeasing’ or ‘angering’ China is a test the PRC leadership may want all nations to consider when thinking through their actions. Trump certainly seems to see beyond this, perhaps because he too is comfortable using ‘the theatre of emotions’ in his own statecraft and negotiations.

This year began with growing tensions in cross-Straits ties, including a recent spat over new commercial air routes launched by China, and the increasing number of patrols by Chinese long-range bombers and spy planes around Taiwan. Taipei counted some 25 such drills by Chinese warplanes between August 2016 and December 2017.

While international attention has been preoccupied with North Korea and the South China Sea, the Taiwan issue remains no less a flashpoint. In fact, arguably it’s the issue that China feels strongest about.

Despite a limited diplomatic network, Taiwan remains a crucial player in maintaining the regional balance. Taiwan also remains a democracy with a successful and vibrant high-technology economy. It’s considerably more important strategically than the scattered artificial islands in the South China Sea.

A scenario where China uses force against a democratic Taiwan would be unwelcome across the region. It would end speculation about the kind of China the world faces under President Xi’s leadership in a way that would destroy the narrative of a shared ‘China dream’.

A scenario where Taiwan remains a democratic, high-technology society with strengthened relationships in North Asia, Europe, the US and elsewhere—while remaining within the diplomatic ‘One China’ framework—is one worth contemplating.

Just days after the signing of the travel act, US senior official Alex Wong, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, met with President Tsai Yin-wen in Taipei. Wong reassured the Taiwanese that US support for Taiwan has never been stronger. The travel act is a significant development in cross-Straits relations. Let’s prepare ourselves for the return of Taiwan as a strategic and security issue that matters.

We’re in Tokyo this week for the fifth Quadrilateral Plus track-two dialogue, along with think tanks from Japan, India and the US. With the Quad starting to get a bit of momentum behind it, it’s time to start thinking about what it might actually do—rather than just talk about—to address the big security issues of our time. This article is adapted from a paper we presented at the meeting.

At the top of the list of issues for the Quad—indeed one of the major reasons the Quad cohered in the first place—is the increasing assertive and at times coercive behaviour of China. China’s militarisation of the South China Sea, an increasingly threatening tone towards Taiwan, border incursions in the Himalayas, and the frequent and often aggressive incursions around the Senkaku Islands are the most obvious practical demonstrations of its emboldened foreign and strategic policy. None of those are helpful in positioning China as a non-revisionist power.

To be fair, when we take a more global view of China’s actions, it doesn’t look as threatening as it does nearer to home—but it isn’t a particularly reassuring picture either. Chinese money talks loudly in the developing world, and it’s used as leverage to get Chinese companies into new places, often as a consequence of soft loans made to governments with little power to resist the funds on offer. Looking at the South Pacific, for example, there are many instances of loans being given for economically marginal ventures, with the locals getting only modest flow-on benefits.

Much of China’s global activity is positive. China is currently the biggest contributor of troops to UN peacekeeping missions, for example, and it would be a stretch to say that selfish motives underlie the current rate of effort. Similarly, the Chinese navy has worked with multinational maritime forces to help police against piracy. China does some things because it wants to be seen as a major power, with the ability to contribute to global efforts, rather than with narrow self-interest as the motivation.

So the aim of any interactions with China should be to encourage behaviour that helps build common goods, while providing disincentives for the more aggressive and unhelpful applications of Chinese power. In recent years China has been very successful in achieving its geopolitical goals, but we should remember that it isn’t an invulnerable colossus.

Weaknesses in elements of China’s power provide potential points of leverage for the Quad countries, especially if we can take a consistent and strategic approach. It’s fashionable in the Western press to talk about how dependent we are on China. That’s especially true in Australia, where the narrative now is that our 26 years of uninterrupted growth are the result of economic ties with China. But that cuts both ways: China needs the rest of the world at least as much as we need it—and may become more dependent as some of its internal structural problems become more obvious. It might be productive for Quad members to think through ways of making those interdependencies clearer. It would certainly help balance a lot of unthinking rhetoric about having no choice but to placate China.

But there’s also a downside risk to the rest of us in Chinese weaknesses. The Communist Party (CCP) has quite skilfully used a combination of appealing to Chinese nationalism and providing economic benefits to strengthen its hold on the country. For most of the past 20 years, the economic element took precedence. Nationalism could be stirred up when it suited and, while an imprecise implement, it probably suited the CCP quite well to have a backdrop of angry nationalists when asserting its position on contested spaces.

But vehement nationalism is a deeply unattractive thing, especially when it’s accompanied by anger at perceived social injustices, and it can lead to disaster if a nation is swept along by it. So the question becomes what happens when there’s a confluence of factors that conspires to release the shackles on Chinese nationalism. An economic downturn, especially one that impacted heavily on China’s relatively newly wealthy middle class, could cause the CCP to try to turn attention away from internal issues towards external ones.

So far China’s assertiveness and unilateral ways have been calculated to not cross the threshold where open conflict is a predictable outcome. China has effectively annexed the South China Sea by never doing anything precipitous, for which a robust military response would be appropriate. Similarly, Beijing backed off the angry rhetoric regarding the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands after President Barack Obama said that the US–Japan Treaty provisions extended over the islands. They didn’t, however, stop the low-level incursions, and in fact have ramped up their frequency—always slowly enough that a big pushback isn’t likely. That calibration depends on Chinese authorities being able to manage and control outbursts of nationalism. Growing public confidence in China’s strength, combined with a desire by the PLA to show what it can do could result in the failure of managed calibration.

It’s now clear that President Xi Jinping sees himself continuing to preside over China for many years to come. His status seems assured, and he has overseen a new level of monitoring and control of public discourse to ensure that his effective takeover is unchallenged. Party control seems solid enough for now, but it might be that the centralisation of power in the person of Xi turns out to be overreach in the party, or overreach in the party’s management of China. It certainly makes it hard for Xi to be associated with failures, and a geopolitical setback might be hard to manage, especially if the economy slows further.

The Quad countries have many strengths as well, and our collective military and economic clout is more than a match for China. We think the Quad can collectively put a bit of a brake on China’s geopolitical ambitions, but there are dangers here. Humiliating China plays into its nationalist narrative, and runs the risk of the CCP acting in response to internal agitation. That shouldn’t stop us from acting in our interests, but we need to factor the risk of inadvertently sparking unrest in China into the calculus of what we might do.

The White House announcement that Admiral Harry B. Harris, the current commander of the US Pacific Command, is President Donald Trump’s choice for ambassador to Australia is unambiguously good news for our alliance relationship. The posting sends the clearest possible signal that the US is intent on strengthening its Asian alliances. Europeans may still puzzle over Trump’s disaffection with NATO, but there should be no doubt that the White House sees America’s alliances in Asia as critical to sustaining an increasingly challenged strategic balance.

Predictably enough, America’s chorus of critics in Australia will seamlessly switch from agonising about Trump’s anticipated withdrawal from Asia to fretting that the president is too closely engaged. Could this White House get credit for anything from the Australian commentariat?

The White House media statement on Harris’s nomination for the post describes him as follows:

A highly decorated, combat proven Naval officer with extensive knowledge, leadership and geo-political expertise in the Indo-Pacific region, he graduated from the US Naval Academy in 1978 and was designated a naval flight officer in 1979. He earned a MPA from Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, a MA from Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service, and attended Oxford University. During his 39-year career, he served in every geographic combatant command and has held seven command assignments.

None of this is hyperbole. The American military has an amazing capacity for producing warrior scholars among its senior leadership—people who think deeply about strategy and international affairs and who aren’t afraid of the instruments of military power that make America the force it is in global affairs. Harris is precisely that kind of strategic thinker. These qualities were clearly on display in the three speeches he delivered at ASPI gatherings. The admiral’s strategic nous is leavened with a self-deprecating sense of humour that works well with Australians. Harry ended a speech he delivered to an ASPI meeting in Brisbane with the line ‘fate rarely calls upon us at a moment of our choosing’ but then admitted the phrase came from the latest Transformers movie. ‘So if you remember nothing else, just remember that you were at ASPI the day when the PACOM Commander stole a line from Optimus Prime.’ Nice one, Admiral!

Australian media commentary has focused on Harris’s blunt language on China. His use at a 2015 ASPI conference of the term ‘great wall of sand’ to describe Chinese island construction in the South China Sea received international media attention at the time and was not appreciated in Beijing. It’s hard to fault the admiral’s assessment. During the height of China’s island construction in 2015 and 2016, the Obama administration spectacularly underestimated the significance of what was happening. Washington dismissed the South China Sea story as just spats over obscure rocks and shoals. Harris was one of the few voices raised to say that the US should be more concerned about Beijing’s construction of military facilities able to control the air and sea space over a region vital to East Asian stability. What a pity Obama didn’t listen. It’s largely ‘game over’ in the South China Sea now, although it remains to be seen when the PLA will demonstrate its newly established reach into an area 80% the size of the Mediterranean, lapping Indonesia’s northern coast.

American ambassadors are typically loath to inject themselves into Australian domestic debates, but one should hope that Harris will help inject a bit of spine into discussions on national security. We should be concerned with the way our public debate is being shaped. Every issue—from Harris’s nomination, to new espionage legislation, to changes in foreign investment decision-making—is now assessed from the perspective of how Beijing will react. Our media gleefully reports criticisms of Australia in the ranting Global Times or the more staid People’s Daily as though the approval of Chinese journalists is the best measure of good Australian policy. Ministers trip over each other as they struggle with talking points designed to say that China isn’t the biggest strategic elephant in the room. The rules-based global order is just taking a little nap, folks, or perhaps pining for the fjords; nothing to worry about here.

What’s really needed is an Australian conversation, shared with our closest friends and allies, about the rapidly eroding strategic outlook in the Asia–Pacific region. North Korea is the immediate problem—now on a brief pause while we pretend that the Winter Olympics has the power to unite the peninsula. Beyond the Korean problem, which for good or ill will be the major focus of 2018, is a China that is rejecting the rules-based global order, building a massive military capability and looking to dominate its neighbours. China wins if we prove incapable of even having a realistic conversation about what this means for Australian security.

Back to Harry B. Harris. As ambassador, his plain speaking may, publicly, take a more diplomatic approach. But he will have a direct line to Trump and, presumably, to Turnbull. Goodness knows the alliance needs an injection of fresh thinking and a willingness to tackle the realities of our worsening strategic outlook. Full marks to Chargé James Caruso and the embassy staff for ably running the mission, but we should hope that the admiral’s Senate confirmation is quick and that Canberra will soon welcome an ambassador uniquely able to help grow the alliance and to develop shared responses to the crumbling rules-based order.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has been hailed as the world’s most ambitious development proposal, costing an estimated US$1 trillion. The BRI promises new railways, roads, ports, energy systems and telecommunications networks across Eurasia; Chinese officials have said that it’ll provide ‘excellent opportunities for countries to improve their network infrastructure with Chinese investment’. One of those opportunities, the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB), involves constructing state-of-the-art trade and network infrastructure linking China, Iran and Russia—and possibly North Korea, following its surprise invitation to the Belt and Road Summit in May 2017.

Australia has been hesitant to join the BRI and to support increased interconnectivity between Russia, China, Iran and potentially North Korea—an implicit outcome of the SREB. Those four countries are among the world’s most aggressive cyber states, and each has executed advanced cyberattacks against Western targets. They’re also home to some of the world’s largest armies, and three of them maintain nuclear weapons. A coalition comprising these four countries could change the geopolitics of Eurasia and challenge the existing global order.

In the Worldwide threat assessment of the US intelligence community, Director of National Intelligence Daniel R. Coats specifically addresses each of these countries and summarises their aggressive posturing. Russia and China, empowered by their nuclear capabilities, have undertaken bold geopolitical expansions into Ukraine and the South China Sea; North Korea is realising its nuclear ambitions despite mounting international sanctions; and Iran has opted to avoid sanctions but remains nuclear latent under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.

In the cyber sphere, we’ve seen Russian interference in the 2016 US presidential election, Chinese hacking of UK firms in 2017, Iranian hacking of US banks in 2016 and, most recently, the theft of South Korean military plans by North Korea.

In November 2016, China and Iran signed a military cooperation agreement and committed to joint military exercises. Trade between the two countries increased by 31% in the first half of 2017: ‘China is not only Iran’s biggest trade partner now but also one of the major investors in our country’, the Iranian ambassador to China told the media. China–Russia trade has enjoyed similar growth. And last July, President Xi Jinping said that bilateral relations with Russia ‘are now the best ever’ as he released three joint statements with President Vladimir Putin. Perhaps more disquieting was the content of those statements, which reflect ideological consensus and forecast increased military and security cooperation across Eurasia.

The growth in Chinese trade with Russia and Iran was greater than the average growth in Chinese trade with countries along the BRI routes, which increased by only 23% over the same period. An economically interconnected Eurasia is conducive to cooperation more generally, but the special emphasis China places on Iran and Russia could precipitate the formation of a coalition of Eurasian powers. That may extend to North Korea, which might gain indirect access to the SREB in exchange for denuclearisation.

The temperament and capability of such a coalition should worry Western onlookers. Each of the four states possesses advanced cyber warfare capabilities, restrained by no perceptible rules of engagement. Data fusion among these countries would rival the information-gathering capabilities we thought unique to our own Five Eyes intelligence-sharing alliance (the US, the UK, Australia, Canada and New Zealand)—albeit built on espionage, political and economic interference, and commercial theft. The global threat posed by this coalition, mutually emboldened, would be far greater than the sum of its parts.

This is possibly one worst-case scenario that the Australian government is grappling with, but it seems the British haven’t been so cautious. At the first Global Sichuan Entrepreneurs conference on the BRI in September 2017, I heard members of British industry express their unreserved support for the initiative during presentations from Chinese and Russian diplomats. The general consensus appears to be that partnering with China will ease Britain’s economic withdrawal from the European Union, while helping China transition into a more sustainable economy for the long term.

Western countries shouldn’t prioritise short-term gains over long-term uncertainty. Their ability to identify and suppress undesirable military and security cooperation in Eurasia will prove critical to the sustainability of such an investment. Australia would be unwise to follow Britain’s lead without safeguarding its long-term interests and understanding the full implications of the BRI.

For the past 50 years in Asia, the economists have consistently beaten the strategists in the crystal ball stakes. Over those decades, you’d have done better going to an economist rather than a strategist to predict Asia’s future.

The economist versus strategist proposition upends the cliché that economists are the gloomy profession. Compared to the defenceniks, the econ-nerds are radiant optimists, putting their faith in the market’s invisible hand and in all of us as rational actors.

Strategists dream up the worst possible scenario, then spend billions to defend against it, based on a simple proposition: if only one low-probability, high-impact nightmares arrives, it’ll ruin your whole day—or decade, or country.

While strategists are happy to have their dark projections proved wrong, economists are never mistaken—they merely rejig the model, refine the theory and demand better statistics.

Over the past 50 years, the economists have got it right in calling Asia’s miracle, while the strategists have been confounded at how the dream keeps delivering.

In The Strategist, these be fighting words. As this journalist is neither economist nor strategist (and, of course, some of my best friends are … etc.), I’ll go quickly to the standard hack defence: consider the facts.

When it comes to facts, my thoughts on Asia’s amazing run are shaped by an economist who has been a trusted guide for decades, Dr Peter McCawley. He has just published a history of 50 years of the Asian Development Bank (ADB), Banking on the future of Asia and the Pacific (download here).

When I sat down with Peter to get my signed copy, the conversation turned to one of his recurring optimistic themes: Asia’s economic rocket is still in the early boost stage, with many more golden decades to go. As McCawley commented: ‘It’s a dazzling story. We’re just at the start. Asia’s economic miracle can run for another 50 years.’

McCawley points to electricity consumption as just one measure of the distance Asia still has to go. In Australia, annual electricity consumption is around 10,000 kWh per person, and in the US it’s 13,000 kWh per person. In India, Indonesia and the Philippines, the figure is about 800 kWh per person.

Asia is still relatively underdeveloped, McCawley says, and there’s a lot of upside to come: ‘They’ve tasted prosperity, and they like it—cars, bigger houses, mobile phones, international travel. The Asian boom will bring lots of troubles, it’s true—more pollution, for example—but the boom will go on nevertheless. Asians are sick of being poor.’

In the book’s conclusion, McCawley cites ADB thinking on what the Asian century could look like by 2050:

If growth in Asia follows recent trajectories, average per capita income could rise sixfold (in purchasing power parity terms) by 2050. In this scenario, the Asian share of global gross domestic product will rise rapidly, from around 28% in 2010 to over 50% in 2050. It is a reasonable assumption that, with half of the world population in Asia, the region will regain the dominant economic position it held before the Industrial Revolution.

The description of the golden future is followed by a quick nod to the strategists’ nightmare: ‘Asia’s rise is not preordained.’ Along with the usual econ-nerd prescriptions about macroeconomic management, infrastructure, health and education, plus open trade and investment regimes, there’s a don’t-stuff-it-up injunction: ‘Hard-won gains in growth and poverty reduction can be quickly lost if there is instability or conflict.’

Asia is already into a huge investment boom. McCawley comments that Asia’s levels of capital accumulation are low; the capital-per-person figure is only 10% of that in the US. The emerging power in rounding up multilateral capital is China.

In 2015, China created two new institutions for financing infrastructure:

McCawley’s book points to a possible division of labour between China’s AIIB and the Asian Development Bank:

AIIB would focus on infrastructure investment and stay away from concessional operations, social sector, policy-based lending, and research work, and … AIIB would aim at being a leaner institution without a resident Board. Because of these different characteristics, there would be more scope to cooperate and complement each other.

McCawley told me that Asia’s ravenous appetite for capital means there’s no need for a fight between the AIIB and ADB: ‘I don’t think there’s a problem. People are saying there’s rivalry, but both of them are relatively small banks. Even the World Bank is a small bank in banking terms. There’s room for another 10 AIIBs or ADBs in Asia.’

The difficulty for China in building Asia’s future, he suggests, is more about culture than cash. Chinese bureaucrats in Asia, McCawley says, ‘often don’t do negotiation very well—they’re not used to dealing with landowners, for instance’. The Chinese government model of seizing any land wanted for development can’t be exported: ‘It’s a big cultural problem. They’re used to doing things in China and this will work nowhere else in Asia.’

A China confronted by culture clash, McCawley suggests, can take some quiet lessons from the 50-year experience of the ADB, especially some habits of mind that Japanese leadership has built into regional development.

McCawley says the ADB is an important example of Asian regionalism:

This bank is interesting because it’s one of the most successful Asian regional organisations. If we’re interested in regionalism, what are the elements of success in this? Why has it worked? I think one of the reasons it’s worked is it’s not Anglo-Saxon. It’s an Asian institution. They have learned to compromise. They know how to go slow. And the Japanese are good at compromise when they want to—they’ll live with India and China.

May the economists continue to call it right.

This month, Sri Lanka, unable to pay the onerous debt to China it has accumulated, formally handed over its strategically located Hambantota port to the Asian giant. It was a major acquisition for China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—which President Xi Jinping calls the ‘project of the century’—and proof of just how effective China’s debt-trap diplomacy can be.

Unlike International Monetary Fund and World Bank lending, Chinese loans are collateralised by strategically important natural assets with high long-term value (even if they lack short-term commercial viability). Hambantota, for example, straddles Indian Ocean trade routes linking Europe, Africa and the Middle East to Asia. In exchange for financing and building the infrastructure that poorer countries need, China demands favourable access to their natural assets, from mineral resources to ports.

Moreover, as Sri Lanka’s experience starkly illustrates, Chinese financing can shackle its ‘partner’ countries. Rather than offering grants or concessionary loans, China provides huge project-related loans at market-based rates, without transparency, much less environmental- or social-impact assessments. As US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson put it recently, with the BRI, China is aiming to define ‘its own rules and norms’.

To strengthen its position further, China has encouraged its companies to bid for outright purchase of strategic ports, where possible. The Mediterranean port of Piraeus, which a Chinese firm acquired for US$436 million from cash-strapped Greece last year, will serve as the BRI’s ‘dragon head’ in Europe.

By wielding its financial clout in this manner, China seeks to kill two birds with one stone. First, it wants to address overcapacity at home by boosting exports. And, second, it hopes to advance its strategic interests, including expanding its diplomatic influence, securing natural resources, promoting the international use of its currency, and gaining a relative advantage over other powers.

China’s predatory approach—and its gloating over securing Hambantota—is ironic, to say the least. In its relationships with smaller countries like Sri Lanka, China is replicating the practices used against it in the European-colonial period, which began with the 1839–1860 Opium Wars and ended with the 1949 communist takeover—a period that China bitterly refers to as its ‘century of humiliation’.

China portrayed the 1997 restoration of its sovereignty over Hong Kong, following more than a century of British administration, as righting a historic injustice. Yet, as Hambantota shows, China is now establishing its own Hong Kong–style neocolonial arrangements. Apparently Xi’s promise of the ‘great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation’ is inextricable from the erosion of smaller states’ sovereignty.

Just as European imperial powers employed gunboat diplomacy to open new markets and colonial outposts, China uses sovereign debt to bend other states to its will, without having to fire a single shot. Like the opium the British exported to China, the easy loans China offers are addictive. And, because China chooses its projects according to their long-term strategic value, they may yield short-term returns that are insufficient for countries to repay their debts. This gives China added leverage, which it can use, say, to force borrowers to swap debt for equity, thereby expanding China’s global footprint by trapping a growing number of countries in debt servitude.

Even the terms of the 99-year Hambantota port lease echo those used to force China to lease its own ports to Western colonial powers. Britain leased the New Territories from China for 99 years in 1898, causing Hong Kong’s landmass to expand by 90%. Yet the 99-year term was fixed merely to help China’s ethnic-Manchu Qing Dynasty save face; the reality was that all acquisitions were believed to be permanent.

Now, China is applying the imperial 99-year lease concept in distant lands. China’s lease agreement over Hambantota, concluded this summer, included a promise that China would shave US$1.1 billion off Sri Lanka’s debt. In 2015, a Chinese firm took out a 99-year lease on Australia’s deep-water port of Darwin—home to more than 1,000 US Marines—for US$388 million.

Similarly, after lending billions of dollars to heavily indebted Djibouti, China established its first overseas military base this year in that tiny but strategic state, just a few miles from a US naval base—the only permanent American military facility in Africa. Trapped in a debt crisis, Djibouti had no choice but to lease land to China for US$20 million per year. China has also used its leverage over Turkmenistan to secure natural gas by pipeline largely on Chinese terms.

Several other countries, from Argentina to Namibia to Laos, have been ensnared in a Chinese debt trap, forcing them to confront agonizing choices in order to stave off default. Kenya’s crushing debt to China now threatens to turn its busy port of Mombasa—the gateway to East Africa—into another Hambantota.

These experiences should serve as a warning that the BRI is essentially an imperial project that aims to bring to fruition the mythical Middle Kingdom. States caught in debt bondage to China risk losing both their most valuable natural assets and their very sovereignty. The new imperial giant’s velvet glove cloaks an iron fist—one with the strength to squeeze the vitality out of smaller countries.

As 2017 limps out and 2018 edges in, here’s Old Dobell’s almanac of the times, trends and twists of history.

Trump-eting: The US system is working, but it’s been a stress test from hell. America’s system will stand, but America’s international standing will suffer huge damage. The Donald breaks with 70 years of US history in Asia.

Accept his inauguration speech as a true statement of intent, based on Trumpian instincts:

My tip: he’ll get re-elected. We’ve got seven more years, unless Trumps gives himself a heart attack from too much dessert. Dating the superpower presidency from FDR, history says America re-elects its presidents.

Forget impeachment. The Republican Party has more to fear from the base than from Trump. A Republican Congress isn’t going to impeach its own voters.

America’s recovery is in its ninth year. The economy hums. Unemployment is 4%. Median earnings are rising and economists predict a ‘new golden age’ for American workers.

China chomps: The Oz foreign policy white paper got it into one sentence in its third paragraph: ‘Today, China is challenging America’s position.’ Even fiendishly complex trends and twists can be simply stated.

Next year, Trump will have to choose his Asia war. He can have trade war with China. Or he can do cold war with North Korea, with China’s acquiescence.

China trade war or Korea cold war: he can’t have both.

Some almanac cheer: The cold war with the Soviet Union was an ideological contest—a European religious war, largely fought in Asia. Today there’s zero ideology between China and America; this is just dollars and power. Donald the deal-maker suits China, and Xi Jinping plays him well.

More cheer: China isn’t a revisionist power like the Soviet Union. China is a status quo tidal power. Beijing loves the status quo. And Beijing knows the tide is moving its way. It wants more of both, on terms that serve the elite (aka the Communist Party) and service a quiescent people.

The nature of Oz: Australia is now a Eurasian country. As George Megalogenis records in the new Australian Foreign Affairs, this is an epic transformation, from Anglo-European to Eurasian.

The shift has gone into hyperdrive this century, fuelled (and peopled) by migration from China and India. Two and a half million of our population were born in Asia. The 2016 census says the languages spoken at home in Oz are, in order, English, Mandarin, Arabic, Cantonese and Vietnamese. Hindi and Tagalog are just outside in the top 10. Country of birth for Australians: China is number four, India number five.

Q: What will history mark as the biggest single change John Howard made to Australia?

A: Migration.

The scale and content of migration since 2001—emphasising skills, lifting numbers—remade the face of Australia. Howard created a Eurasian country in double-quick time. The man who said we didn’t need to choose between history and geography has shifted our history by embracing our geography. The law of unintended consequences has a wicked sense of humour.

Date the Eurasia project from 1972, the point Howard uses in his memoirs for the shift from excluding Asia to engagement. The early decades of the project involved openings, collaboration and what Bob Hawke called enmeshment.

The new stage—as we comprehend our Eurasian achievement—is Australia being changed by Asia. Such internal forces alter a nation’s foreign policy.

Oz–Eurasian foreign policy: Canberra’s international approach mixes Western language, US alliance and ASEAN flavour. We’re louder than ASEAN, but our positions increasingly match.

Australia does the ASEAN dance on Myanmar and the Rohingya crisis, on dealing with a murderous president in the Philippines and, as ever, on the central place of Indonesia in our future and our neighbourhood. Oz policy on the South China Sea is ASEAN’s policy with the volume turned up.

We share ASEAN’s dreams and nightmares on China. Like ASEAN, China is a presence in our people as well as in our policy. Ask Sam Dastyari or Andrew Robb how that works.

In March, the first Australia–ASEAN summit on Australian soil happens in Sydney. The foreign policy white paper is almost lyrical, as it should be:

Southeast Asia frames Australia’s northern approaches and is of profound significance for our future. ASEAN’s success has helped support regional security and prosperity for 50 years … Southeast Asia is the nexus of strategic competition, testing the region’s cohesion and ASEAN’s central role.

This almanac proclaims the Sydney summit the start of the march to Australian membership of ASEAN in 2024, the 50th anniversary of Australia becoming ASEAN’s first dialogue partner.

Uncertain era: The tyranny of the present reigns if we moan about uniquely uncertain times. Such anguish says more about Canberra than it does about the state of the world. We’ve lived through vastly more dangerous eras. Australia’s conceptual framework is being shaken, our long-term relative decline as a power and an economy in Asia proceeds as it has for decades, and the new fear is our feckless great and powerful friend. The simple response to the hand-wringing is that we’re born to uncertainty and live it all our days.

The wonderful Simon Leys, in his collection of bon mots, offers these:

Pedro Calderon: ‘The worst is not always certain.’

Nietzsche: ‘It’s certainty, not doubt, that causes madness.’

Let us fret less. And head to Christmas intoning a thought attributed to Benjamin Franklin: ‘Beer, beer, beer … beer is proof that God loves us and wants us to be happy.’

China has defied expectations yet again. President Xi Jinping, the chief of the Chinese Communist Party, was widely expected to face his toughest test so far in October, when the CCP convened its 19th National Congress to choose its next leadership. Though Xi was guaranteed a second five-year term, it was thought that he would run into serious opposition if he refused to appoint a successor. But he did just that—and the opposition never materialised.

The reason is simple: Xi was prepared. Since taking office in 2012, he has carried out a sustained crackdown on civil society, unleashing a wave of repression few thought would be possible in post-Mao China. He also pursued a large-scale anti-corruption campaign, which constrained and even eliminated potential political rivals, thereby enabling him to consolidate his power swiftly.

Early this year, when Chinese security agents abducted Xiao Jianhua, a China-born Hong Kong–based billionaire, to serve as a potential witness against senior leaders, any remaining resistance to Xi’s push for greater authority was decimated. Nonetheless, to strengthen his position further in the run-up to the congress, a sitting Politburo member who was viewed as a possible successor was abruptly arrested on corruption charges in July.

When the congress finally arrived, Xi capitalised on this momentum to install two of his allies in the Politburo Standing Committee, the party’s top decision-making body. And, by preventing the CCP from designating a successor, he has opened the door to a third term in 2022.

Judging by any conventional measure, Xi has thus emerged from 2017 more powerful than ever. The question now is whether he can use that power to translate his vision for China—particularly for its economy—into reality.

On this front, Xi made important progress in his first term, single-handedly corralling the Chinese bureaucracy to implement his ambitious but risky ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI). That plan entails the use of Chinese financing, materials and expertise to build infrastructure linking countries throughout Asia, Africa and Europe to the global economic juggernaut that China has become.

But, even with his significantly augmented power, Xi’s continued success in implementing his economic vision is uncertain, at best, owing precisely to the ideological indoctrination and repression that underpin his authority. Despite the propaganda blitz lauding his vision for China, it is doubtful that many Chinese, including CCP members, really believe that their country’s future lies in a centralised, fear-based authoritarian regime.

In fact, while overt resistance to Xi’s vision is difficult to find—it is, after all, exceedingly dangerous nowadays—passive resistance is pervasive. And Xi’s toughest opponents are not members of China’s tiny dissident community, but rather the party bureaucrats who have borne the brunt of his anti-corruption drive, not just losing considerable illicit income and advantages, but also being subjected to unrelenting dread of politicised investigations.

Unless Xi can regain the support of the party’s mid- and lower-level officials, his plan to remake China could fizzle out. After all, however powerful he might be, he cannot escape the reality captured by the ancient Chinese adage, ‘Mountains are high and the emperor is far away.’ And, without the promise of sufficient material reward, China’s apparatchiks may subscribe to the logic that prevailed among citizens of the former Soviet bloc countries: ‘We pretend to work, and they pretend to pay us.’

Beyond a recalcitrant bureaucracy, Xi might confront a serious challenge from the so-called Youth League faction of the CCP, affiliated with former president Hu Jintao. With two seats on the new seven-member Politburo Standing Committee being held by protégés of Hu, a power struggle between the Youth League and Xi’s faction cannot be ruled out.

Of course, it is possible that Xi can overcome resistance from the Youth League. After all, he has already largely vanquished the faction connected to former president Jiang Zemin, which previously constituted the most powerful rival group within the CCP. But even if Xi subdues the Youth League, he will be left with a regime that is more fractured and dispirited.

Xi also faces significant policy challenges. On the economic front, he will have to contend with soaring debts and overcapacity, which, together with a shift towards protectionism in President Donald Trump’s America, could depress growth further. In foreign policy, too, Xi will confront a deteriorating relationship with the United States, fueled by the intensifying North Korean nuclear threat and China’s own aggressive behavior in the South China Sea.

The new conventional wisdom is that Xi will be able to steamroll his colleagues in 2022, regardless of his performance in the coming five years. This might be true. But political authority is ephemeral, especially for leaders who lack a solid economic track record. For now, Xi and his supporters have reason to celebrate. But they should not count on raising their glasses in five years.

In the last year, the single most pointless wound inflicted by the US on Asia, not to mention itself, was its abandonment of the Trans-Pacific Partnership. In one fell swoop, the once great free-trading nation that was the United States of America died, leaving the global trading system utterly rudderless.

With America’s spurning of the TPP, not only was progress towards further trade liberalisation reversed; the global free-trade system itself, including its common rules and arbitration mechanisms for resolving disputes, came into question.

You don’t have to be a Marxist to understand that economics has a profound and probably even decisive impact on politics, both national and international. And, indeed, the geopolitical and geoeconomic implications of US President Donald Trump’s move are just beginning to be felt across the Pacific.

With China’s economic footprint across the Asia–Pacific region already large, countries in the region are now increasingly concluding that the US is consigning itself to growing economic irrelevance in Asia. US financial institutions will, of course, remain important, as will Silicon Valley, as a source of extraordinary innovation. But the pattern of trade, the direction of investment, and, increasingly, the nature of intra-regional capital flows, are painting a vastly different picture for the future than the one that has dominated post-war Asia.

The abandonment of the TPP—a key campaign promise that Trump fulfilled almost immediately upon taking office—reflects the collective failure on the part of the American political class in the 2016 presidential election. Continuing that failure, America’s leadership has not followed up on the decision with much of anything.

At home, the Trump administration has engaged in much chest-thumping about ‘America First’. Abroad, it has begun to tout an ill-defined concept of ‘a free and open Indo-Pacific’, which displays all the hallmarks of a slogan in search of substance. What economic reality will hang beneath this shingle, we know not. If the idea is a series of individual bilateral free-trade agreements, any seasoned observer of US trade diplomacy can tell you that we are looking at a decade’s worth of negotiations that, ultimately, will probably yield very little.

For their part, Asia–Pacific countries have begun to look to two unlikely sources for leadership on trade liberalisation: Japan and China.

Japan has sought to pull the TPP’s remains out of the ashes by creating the TPP 11, which includes all of the original negotiating states, except the US, which would be permitted to rejoin later. The core tenets of this agreement were signed, despite reservations from Canada, at the November Asia–Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in Da Nang, Vietnam (a meeting that Trump himself also attended), highlighting Asia–Pacific countries’ view that they are no longer chained to US leadership. The so-called Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership represents a significant advance in terms of trade and investment liberalisation across the 11 signatory countries. As for the US, we can only hope that a future administration, whether Republican or Democrat, will see its way clear to acceding to an agreement that Japanese economic leadership has sought to keep alive. But, given the evidence, that may be farfetched.

The other surprising source of trade leadership in the Asia–Pacific region is China. Some years ago, the country began championing a Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). While this will not represent a high-ambition arrangement, it will represent some advancement from the status quo. It embraces 16 states, including China, India, Japan and South Korea, but excludes the US.

India, the third-largest economy in Asia, could also have a critical role to play in furthering pan-regional trade liberalisation. But Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government has yet to direct its political capital towards becoming a member of APEC, let alone advance a trade-liberalisation agenda of its own. This needs to change, but the forces of mercantilism are alive and well in Delhi.

The net result of these developments, with the US having eschewed both the TPP and RCEP, has been a further diminution of American power in the Asia–Pacific region. In fact, the US is increasingly emerging as an incomplete superpower. It remains a formidable military actor, with unique power-projection capabilities that extend far beyond its aircraft carrier battle groups to include an array of other capabilities that are as yet unmatched by other countries in the Asia–Pacific region. But its relevance to the region’s future—in terms of employment, trade and investment growth, as well as sustainable development—is declining fast.

Some in Washington DC seem to think that the US can sustain this pattern for decades to come. But many of us are skeptical. Unless and until the US chooses comprehensive economic re-engagement with the region, its significance to the overall future of Asia, the world’s most economically dynamic region, will continue to fade.

Precisely how other regional powers—China, Japan, India and South Korea (Asia’s four leading economies)—will respond to this decline remains to be seen. But the truth confronting those who observe the region closely is that Southeast Asia has already begun to move meaningfully towards China’s strategic orbit.

Ultimately, the policies of an administration committed to putting America first are likely, in Asia at least, to result in America being put last.

Foreign policy white papers are strange creatures. As the past 14 years amply demonstrate, they’re not necessary for the conduct of effective foreign policy. They are expensive and they expend diplomatic capital by signalling policy positions that might otherwise be carefully obscured. And they can become obsolete with frightening rapidity. In some respects, they are something of an indulgence.

Over the past half-decade, it has become clear that the international order is undergoing a number of significant convulsions. While the consequences will remain uncertain for some time, they present the most significant challenges Australia has faced since 1945. Yet there has been little public debate about the profound nature of these challenges, how we should manage them, and the costs that might be imposed on us in meeting them. The 2017 foreign policy white paper has begun what should be a wide-ranging public debate about Australia’s future.

The paper’s unequivocal advocacy for liberalism—at home and abroad—is extremely welcome. It’s important that a country like Australia nail its colours to the mast at a time when liberal ideas face significant headwinds. That the values at the centre of Australian society are also at the heart of the country’s international engagement is encouraging intellectually and politically.

The paper makes clear that the main purpose of Australian foreign policy over the coming years is to defend the economic and strategic status quo in the region. By this I mean an open and broadly liberal international economic order, a strategic balance favourable to Australia’s interests, and a set of rules and institutions that guides the behaviour of states.

The principal threat the status quo faces comes from the changing distribution of power represented most acutely by China’s revival, but also by the growth of India, Indonesia and other large emerging powers. None of those countries can be depended on alone or collectively to sustain a liberal order. Indeed, some appear to want to change at least some aspects of that order.

The other challenge comes from doubts about America’s capacity and will to play the kind of role it has in the past. The US will continue to be a large economy and considerable military power. But the election of Donald Trump showed allies and friends that Washington couldn’t be depended on to think about its stake in the international order in the same way forever. While Trump will eventually leave the White House, the forces that brought him to office aren’t going away. Moreover, the turn against an expansive global role for the US began more than a decade ago and shows no sign of abating.

Australia’s aim is to have strong relationships with both China and the US. Canberra will aim to coax Beijing into seeing the benefits of the status quo, while it will encourage Washington as much as possible to play a leadership role in Asia. But, ultimately, Australia’s foreign policy will be shaped most profoundly by the extent to which the US and China contest one another’s regional role. And here our capacity to influence events will be marginal.

The bigger question isn’t how the US manages its regional role but what China wants from Asia—and indeed the world. The ambition on display at the 19th Party Congress wasn’t especially comforting, although efforts by Xi Jinping at APEC to present China as a defender of economic openness should provide some slivers of comfort if those words can be taken at face value.

Few doubt that China will contest American influence in the region, but how much and at what cost is far from clear. It has already begun to create regional institutions to advance those interests, principally in its Western periphery. But one shouldn’t assume that its ambition will remain only on the Eurasian Steppes. The paper is fairly quiet about what Australia should do in relation to China, except for the slightly jolting statement on page 27 that Canberra will need to do more to shape a favourable strategic balance.

The paper emphasises the importance of developing partnerships with liberally inclined countries so that we share the burden of supporting the status quo—with the focus on South Korea, India, Japan and Indonesia. These are important and necessary steps to buttress an order under strain. But if the US continues to walk away from liberal internationalism, the five ‘Indo-Pacific democracies’—even if they could align their interests and significantly ramp up their military capabilities—might not fill the considerable gap that would be left.

The paper grapples with the big issues confronting Australia, but it can’t dismiss the reality that we remain dependent on the US, an ally that has become increasingly unreliable. That dependence has less to do with the bilateral security guarantee than the load-bearing role the US has played in maintaining a liberal, rules-based economic order and a stable and beneficial strategic balance.

As Washington wobbles and authoritarian powers rise, the world has become a more challenging place for liberalism. The paper does well to illustrate the nature of the challenges Australia faces and the need to take significant steps to sustain the status quo. But it doesn’t fully acknowledge how hard the defence of that order will be.