The role of soft power in China’s influence in the Pacific islands

Just why the concept of soft power has become such an accepted explanation for the spread of Chinese influence in the Pacific islands is something of a conundrum. (The term ‘Pacific islands’ is used here with the narrow meaning of the small member states of the Pacific Islands Forum.)

There seems to be little evidence that regional states have the sort of admiration for, and desire to emulate, China’s political or economic systems in the way Joseph Nye framed his idea about the attractive power of non-coercive influence.

It was the geopolitics of the Cold War that motivated China to seek a place in the Pacific island sun, not some soft-power pull from regional states seeking to a model to follow. And, for nearly two decades afterwards, Beijing scarcely made a ripple in the regional lagoon, which ended with a flurry of ‘dollar diplomacy’ competition with Taipei for recognition.

A main motivator for applying the soft-power lens in this case appears to be the need to find some rationalisation for China’s dramatic emergence to the centre of the regional stage as an economic, developmental and social influence and the consequential diminishing of the region’s reliance on its traditional ties.

A just-released ASPI special report, Chinese influence in the Pacific islands: the yin and yang of soft power, finds that the concept of soft power is overrated as an explanation for Chinese influence in the Pacific islands.

The apparent fragility of Australian soft power in the region has less to do with the strength of Chinese soft power than a perception that Canberra has drifted away from the regional consensus on climate change, development priorities and economic relations.

This is not to deny Beijing’s interest in developing its soft-power imprint. China reportedly has been spending an estimated US$10 billion annually for over a decade to promote its soft-power message globally. Yet, despite this effort, international indices of soft power show that China is making little headway statistically.

The report supports this broader conclusion, noting that China’s current soft-power influence in the Pacific island region ‘lacks breadth and depth’. There are some significant caveats, however, to this assessment.

The metrics of soft power tend to favour liberal images of the state, so people-to-people attitudes and public diplomacy figure prominently, as do measures of civic influences on foreign policy. By contrast, China has tended to focus its public diplomacy on elites who can deliver pragmatic results for China in achieving its international relations objectives.

China’s approach to soft power is very much in evolution. It has varied over the two decades since the state made a political decision to pursue it as an avenue for foreign policy influence.

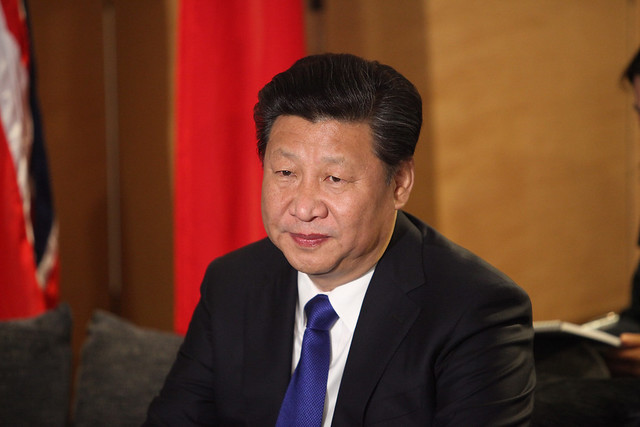

President Hu Jintao advanced the narrative of a ‘peaceful rise’ as a soft-power approach to promote acceptance of growing engagement with the rest of the world. President Xi Jinping has taken a more overtly demonstrative approach to securing admiration and respect internationally.

Thus, international incidents, including some well-documented examples in the Pacific islands, reported in Western media as setbacks for Chinese soft power appear less important to Xi than establishing that respect for China is non-negotiable—almost no matter how small the slight.

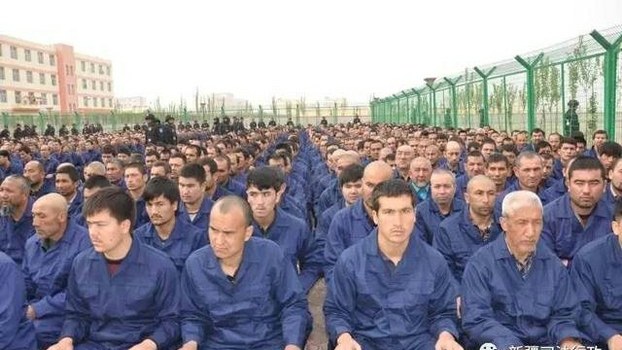

The economic miracle of China excites approbation in the Pacific islands as it has in other parts of the developing world. However, there’s no public support for adopting the Chinese economy as a model for economic reform in the Pacific. The same is true for China’s political system.

The lack of democratic accountability and transparency serve as soft-power deficits for China. The recent 2019 Belt and Road Forum exposed these as significant soft-power weaknesses that are undermining, it’s claimed, Xi’s important message of reassurance to participants that he was dealing with their concerns about the debt and risks associated with his signature Belt and Road Initiative.

A key advantage of having soft power is the inherent trust between states that it embodies. The ‘debt trap’ meme is far more publicly understood in the Pacific islands than any of the putative ‘win–win’ benefits of participating in the BRI.

Indeed, Papua New Guinea’s Prime Minister Peter O’Neill, who was the only head of government from the Pacific islands states at the BRI forum, appears to have been a victim of the so-called debt trap. Five government party members resigned from the party while O’Neill was in Beijing, in part over concern that he was there to acquire more debt.

Overemphasising the role of soft power in the spreading reach of Chinese influence across the Pacific islands comes at a cost. It seems to have been embraced by some policymakers as a challenge to be neutralised. The ASPI report argues that this would be an error.

To attempt to pursue such a course would raise tensions in the region by suggesting to long-time regional friends that they should choose sides. As Pacific Islands Forum Secretary-General Dame Meg Taylor has argued, the region does not want to be asked to make a choice between China and its traditional friends.

Rather, as outlined in the report, Australia will be better served to keep the soft-power balance in its favour by leveraging its much more extensive and well-established soft-power strengths in the region to secure the mutual benefits our neighbours expect from us.