The Chinese Communist Party’s ‘people’s war’ on Covid-19

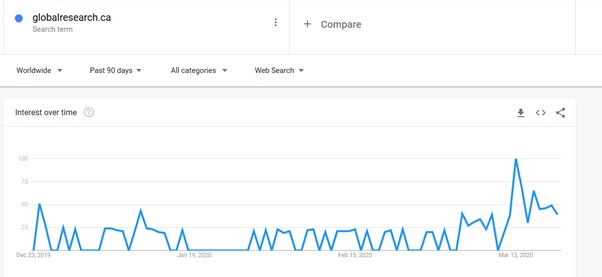

The novel coronavirus first appeared in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. It spread throughout the nation in January, and then across the world. Now, there are over 1.2 million confirmed cases across more than 183 countries and regions.

The Chinese state’s slow response to the outbreak and its lack of transparency have led some to claim that Covid-19 will be China’s ‘Chernobyl moment’. These criticisms remain valid despite China’s later mobilisation to contain the virus’s spread, which was largely the result of work by medical professionals and a strong community response. The Chinese Communist Party’s ineffective command and control mechanisms and its uncompromising restrictions on information in the early stages of the crisis helped transform a localised epidemic into a global pandemic.

Chinese authorities only confirmed the outbreak three weeks after the first cases emerged in Wuhan. As the virus spread, the CCP’s crisis-response mechanisms slowly kicked into gear. On 20 January, President Xi Jinping convened a politburo meeting, which put China on an effective war footing. Wuhan and all major Chinese cities were locked down and the People’s Liberation Army assumed command over disease control efforts.

Shortly after the politburo met, an order was issued to the National Defence Mobilisation Department (NDMD) of the Central Military Commission to launch an emergency response to combat the epidemic. The order required the ‘national defence mobilisation system to assume command of garrison troops, military support forces, and local party committees and governments at all levels’.

As ASPI’s Samantha Hoffman has noted, the NDMD ‘creates a political and technical capacity to better guarantee rapid, cohesive, and effective response to an emergency in compliance with the core leadership’s orders’. To that end, the NDMD has subordinate departments at the provincial level responsible for mobilising economic, political and scientific information and equipment and organising militia, transport readiness and air defence.

The CCP’s defence mobilisation system is based on the Maoist ‘people’s war’ doctrine, which relies on China’s size and people to defend the country from attack. The aim is to lure the aggressor deep into the battlefield, wear them down and then strike decisively. In this whole-of-society approach, civilians, militia and the PLA all play a part.

On 26 January, the World Health Organization reported 1,985 Covid-19 cases in China. One day later, premier Li Keqiang, by then in charge of containing the outbreak, visited Wuhan to inspect its disease control measures. On 2 February, Li and Wang Huning (a member of the politburo and one of the top leaders of the CCP) chaired a meeting of the Central Leading Small Group for Work to Counter the Coronavirus Infection Pneumonia Epidemic (新型冠状病毒感染肺炎疫情工作领导小组). Chinese authorities were starting to develop situational awareness as Covid-19 spread to all provinces.

The number of confirmed cases more than doubled from 11,821 on 1 February to 24,363 on 5 February. On 6 February, Chinese state media reported that Xi had referred to a ‘people’s war’ in a telephone call with Saudi Arabia’s King Salman. News of Xi’s declaration reached Western media, which had earlier noted his public absence. On 7 February, Li Wenliang—the doctor detained by police for alerting the public to the virus in November 2019—died of Covid-19, triggering significant public anger and frustration at the Chinese authorities.

The CCP attempted to neutralise this anger by having officials and public figures express sympathy for Li Wenliang on social media. As public discontent waned, Xi took a more prominent role in the national response. His visit to Beijing’s disease control centre was covered by state media outlets, indicating that his ‘people’s war’ declaration was intended to garner public support for his campaign.

The CCP’s next step was to shore up support within the PLA. On 11 February, the PLA’s official newspaper, the People’s Liberation Army Daily, ran an editorial explaining the urgency and achievability of the mission and followed that with numerous articles that sought to boost the PLA’s morale. The messaging was intended to ensure that the party had the military’s absolute cooperation.

China’s leadership took an early step by constructing the Huoshenshan Novel Coronavirus Specialist Hospital in Wuhan, modelled on the Xiaotangshan Hospital that was built to treat SARS in 2003. First to be mobilised were state-owned enterprises, which erected the hospital in 10 days starting on 23 January. Next, militia units installed medical equipment and beds while others disseminated propaganda via social media to publicise the hospital and other CCP initiatives between 25 January and 1 February.

When construction finished on 2 February, command of the hospital was transferred to the PLA. The Joint Logistics Support Force sent 950 medical workers and resources to support disease control measures. The PLA then deployed a further 450 personnel from its medical universities to treat patients.

Despite having clear processes, issues with command and control linger in the whole-of-society approach to national defence mobilisation. The CCP’s initial response was to suppress all information about the virus generated by the public or medical workers. Even if local officials had early warning of the severity of the threat, it’s likely that they were reluctant to pass on bad news to Xi Jinping. That could explain the three-week lag in the central government’s response. Incentive structures within the government make rapid response—a crucial element of effective crisis management—a hard task for the CCP.

There are also questions about Xi’s control over the PLA during the crisis. Shortly after PLA personnel were deployed to Huoshenshan Hospital, an article in the PLA Daily claimed that there had been no impact on military training, pointing to a series of exercises in the Taiwan Strait and elsewhere. Another article in the PLA Daily reassured personnel that combat power would not suffer, despite resources being allocated to disease control. The exercises and reports gave the impression that Xi was trying to placate the PLA. Weak civilian control over the military could prove a lingering vulnerability in China’s response to a future epidemic.

The deployment of state-owned enterprises, the militia and the PLA was a major test for the CCP’s mobilisation system. While it proved effective in the middle and later stages of the pandemic, the lack of transparency and poor command and control systems in the early stages heightened the risk to international public health to unacceptable levels.

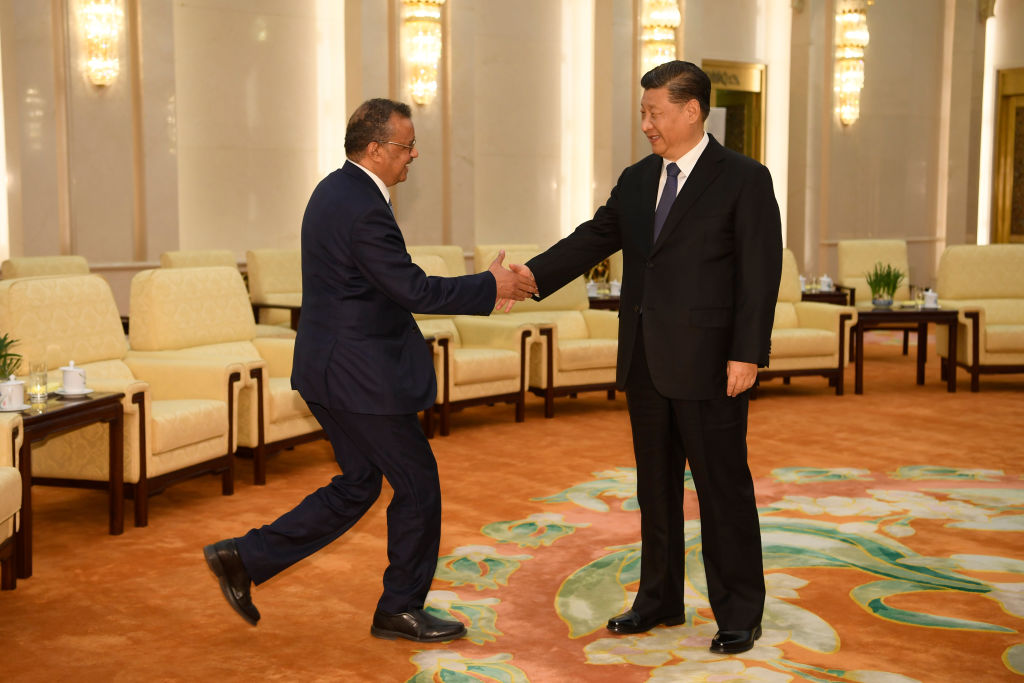

Effective crisis management requires more than whole-of-society mobilisation. A senior WHO official, Michael Ryan, observed that Covid-19 ‘will get you if you don’t move quickly’. If there’s anything to learn from the CCP’s response, it’s that decisiveness, transparency and rapid response are crucial to effective disease control in a crisis.

It appears that Xi did too little before it was too late.