Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

A major disruptive crisis can force countries to adapt in ways that are deeply uncomfortable to the authors of the old order. That is what is happening with the Covid-19 pandemic.

The world is being pushed into a deep economic depression. Political systems everywhere are struggling to cope with a medical emergency but have yet to grapple with the second-order and third-order effects of the pandemic that could reshape the global strategic balance.

For Australia, it’s a wonderful outcome that we have—so far—‘flattened the curve’ and can start to plan for a slow return to normality, but that’s unlikely to be the story in our region. Who knows what Covid-19 will do to Papua New Guinea or Indonesia?

So, to say that national security is ‘not a first-order priority’ for government, as Dennis Richardson told Paul Kelly in the Weekend Australian last Saturday, is a failure of strategic imagination. There will be no snapback to the previous, more comfortable order.

A brief historical detour will help explain my point. As the head of the Department of Defence’s strategic policy branch in 1998, I was given the job of writing a classified assessment of regional security. This was in the aftermath of a murderous civil war on Bougainville Island, the Sandline crisis, which came close to triggering a coup in Port Moresby, and rising violence in East Timor.

I wrote in the assessment that Australia was facing the consequences of a deterioration in regional security. That judgement was set upon by others. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade took it as a criticism of its diplomatic skills, and the intelligence agencies saw it as a negative judgement about their predictive abilities.

As 1998 turned into 1999, it became clear that the assessment would never see the light of day. The Canberra bureaucracy could not conceive that the world was changing faster than its pragmatic incrementalism could handle. The report was shelved. Soon after, I was helping to run a new group called the East Timor policy unit in the weeks before Australia’s biggest military operation since the Vietnam War. Some deterioration!

The Timor crisis looks like a mosquito bite compared with the strategic changes now underway. Richardson dismisses as far-fetched the idea that ‘Australia’s circumstances are so dire, almost at the point of war, that we need a national security focus dominating the totality of what the government does’.

The risk of conflict is not far-fetched. The Chinese Communist Party is pushing the boundaries of acceptable international behaviour in the skies and seas around Taiwan, Japan and South Korea, and in the South China Sea. This is not a state secret. It’s readily observable by reading Chinese newspapers that the party is stoking nationalist sentiment, diverting attention away from its mismanagement of the virus, and setting the groundwork for a crisis over Taiwan.

I hope a military crisis doesn’t happen, but it is the responsibility of national security agencies in Australia to think through the consequences of high-risk scenarios.

This is why Australia needs a national security strategy. Even if it were possible for Australia to avoid direct military involvement in a Taiwan crisis (a big if), we would certainly feel the impact of fuel supply chains from north Asia shutting down. Would China be supplying us with medical equipment as normal? If China is locked in a hostile standoff with the US over Taiwan, will we still be welcoming the PRC’s purchasing of our critical infrastructure?

These questions point to the inadequacies of current policy approaches that were designed for a more benign era, when more people bought the fiction that a wealthier China was going to become a more open country to deal with. We do indeed have ‘a muddle of policies that don’t align with one another’, as Richardson puts it. But don’t expect many in Canberra to acknowledge that, because they own the muddle.

In calling for a national security strategy, I am not saying that we should put a ‘national security umbrella over the totality of government’—whatever that means. Australia still will trade, take foreign investment, train overseas students and establish research links with other countries, but we need to understand what these actions mean from a national security perspective.

I agree with Richardson when he says the national security community lacks the skill set to handle these wider tasks. The deficit comes about because we have failed to take these broader challenges seriously.

Nowhere is that more apparent than in our failure to manage foreign investment with greater attention to national security. When I was in Defence, the line was ‘Treasury never says no’ to foreign investment.

The Foreign Investment Review Board has toughened its stance somewhat, meaning appalling stuff-ups such as leasing the Port of Darwin to a Chinese company for 99 years hopefully will never happen again. But it persists in claiming that investment from communist China is no different to investment from democracies. After Covid, does anyone still believe that?

I will happily accept Richardson’s mantle of being a ‘national security cowboy’. Right now, Australia needs more cowboy and less kowtow, more principle and less of the ‘pragmatism’ that has brought us to this sorry point.

On 14 April, as China’s Haiyang Dizhi 8 survey group sailed into the South China Sea again, Taiwan scrambled ships to monitor the passage of the Chinese navy’s Liaoning aircraft carrier strike group as it went through the Miyako Strait near Okinawa and turned south.

According to a MarineTraffic report on 23 April, the carrier group was operating near Macclesfield Bank, and the survey group was shadowing a Philippines-flagged drilling ship that had been contracted by Malaysia to survey for oil in its exclusive economic zone near the overlapping waters between Malaysia and Vietnam.

This is the third time in recent years that China’s naval activities have threatened a maritime crisis for Vietnam. In May 2014, the Haiyang Dizhi 981 oil rig was parked in Vietnam’s EEZ, and from July to October 2019 the Haiyang Dizhi 8, escorted by armed coastguard vessels, surveyed extensively near the Vanguard Bank, resulting in a month-long standoff with Vietnam.

Now, the Haiyang Dizhi 8 and its escorts appear to be pressuring Malaysia’s new government as they did with Vietnam. While this new standoff was over by 25 April, China’s bullying in the South China Sea won’t stop there, at least for Malaysia, Vietnam, and Indonesia.

This manoeuvring has come at a time when the Covid-19 crisis has disrupted US ship deployments. At least two US aircraft carriers have had rotations delayed, upsetting the balance of forces between the US and China in this region in China’s favour.

On 22 April, the US Indo-Pacific Command confirmed that the cruiser USS Bunker Hill, amphibious assault ship USS America, destroyer USS Barry and Australian frigate HMAS Parramatta conducted an exercise in the same region. In the event of a clash, the US and Australian ships would have been outnumbered by People’s Liberation Army Navy vessels.

The Covid-19 crisis is contributing to the erosion of US air and naval dominance in the region and has driven China to take new and bolder actions. In these circumstances, Vietnam and ASEAN need to rethink the institutional basis of ASEAN and consider how it can better protect the security of each country and the ASEAN community.

Compared with other ASEAN countries, Vietnam is in a key strategic position and has taken a tougher stance on the South China Sea. In 2020, it has new roles to play as ASEAN chair and as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council. China is aware that the harder it pushes Vietnam, the closer Hanoi will move towards the US.

But China also believes that if it can intimidate Vietnam, it might be able to manipulate ASEAN and keep the US out of the South China Sea.

On 30 March, Vietnam handed a note to the UN secretary-general detailing its sovereignty over the Hoang Sa (Paracel) and Truong Sa (Spratly) islands and rejecting China’s arguments on the South China Sea. On 17 April, China sent its own note to the UN as part of its ‘three warfare doctrine’—applying psychology, communication and law.

There’s concern that China may seek to exploit the global uncertainty and try to take Vietnam’s vulnerable offshore resources near Vanguard Bank or park an oil rig or a structure on Whitsun Reef. China may even declare an ‘air defense identification zone’ in part of the South China Sea.

To thwart China’s ambitions and to fill the strategic vacuum being left by the US, Southeast Asia needs a new regional security architecture. That could take the form of an stronger ‘Quad-plus’ arrangement, in which the US, Japan, India and Australia work more closely on regional security cooperation with New Zealand, South Korea, Vietnam and possibly Indonesia and Malaysia. Such a grouping also could enable Japan to play a stronger security role in the South China Sea.

Former US national security adviser H.R. McMaster recently wrote that China’s ambition is fuelled by insecurity and that its outward confidence covers an inner fear. He identified three prongs of Chinese strategy: ‘co-option, coercion, and concealment’ and, in an apparent dig at current US policy, argued that America’s ‘strategic narcissism’ should be replaced by ‘strategic empathy’ with regional partners.

The pandemic provides good reason to further reform ASEAN. It has been suggested that Vietnam’s ASEAN chairmanship should be extended into 2021 to make up for the time lost to dealing with the pandemic. If that happens, Hanoi could focus on strengthening ASEAN to face the growing strategic challenges in a post-pandemic world.

For example, the ‘ASEAN consensus’—the requirement that decisions must be supported by all 10 to be binding—should be replaced with a requirement for a two-thirds majority. The ‘non-interference’ principle, under which member nations reject outside intervention, should be qualified to allow exceptions to ensure regional security. ASEAN should also take steps to identify itself with the new Indo-Pacific vision to ensure national and regional security, and the new code of conduct for the South China Sea should be based on the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

The harder China pushes ASEAN countries, the faster it will drive them to greater unity to defend their sovereignty and vital interests.

China wants to divide the ASEAN nations like scattered chopsticks so that it can break them one by one. It wants only bilateral, not multilateral, negotiations to keep the US and the West out of the region. If China controls the South China Sea, ASEAN will face Balkanisation, with its members vassal states to China.

ASEAN countries should put aside their maritime disputes to build a new ASEAN consensus.

Vietnam should pursue national and regional institutional renovation and shift away from its ideological crossroads, where it’s caught between the US and China, to achieve sustainable economic growth and greater strategic resilience.

As Vietnam tries to be less dependent on China on many fronts, it should defend its sovereignty and vital interests in the South China Sea. It should bring the South China Sea disputes to UN forums and the Permanent Court of Arbitration.

Vietnam and ASEAN, with other partners that share a vision for regional security and stability, should build deterrent capabilities based on their own strengths, international cooperation and their willingness to fight.

Vietnam missed two major opportunities for reform and development in the years after national reunification. The first was the failure to achieve normalisation with the US after the Vietnam War. The second was the failure to achieve both economic and political reform after communism collapsed in the Soviet Union.

Now, as the pandemic brings both calamity and impetus for change, Vietnam should not lose the third opportunity that this new turning point offers.

Australia’s ‘step-up’ program in the South Pacific may already be having an impact, at least in Papua New Guinea.

The program was developed to enable Australia to work with other nations, including New Zealand, the United States and Japan, in part to counter the escalating influence of the People’s Republic of China in the region.

There are signs that it’s bringing results.

The PNG government’s decision to effectively nationalise the Porgera Gold Mine raised immediate concerns (which I shared) that China might seize the opportunity to acquire the mine from the PNG government or to claim the right to run the mine.

However, the extraordinarily strong reaction to the decision by one of the Porgera Joint Venture partners, the Chinese-owned company Zijin Mining, which has close links to the Chinese Communist Party, suggests that’s unlikely to happen.

Zijin chairman Chen Jinghe wrote to PNG Prime Minister James Marape condemning the decision not to extend the lease and warning that it could seriously affect future Chinese investment in PNG.

Zijin’s response was even tougher than that of its partner in the joint venture, Canada-based Barrick Gold Corporation, which also condemned the decision. Legal proceedings brought by the mine’s operator, Barrick (Niugini) Limited, against the PNG government are now underway in the national court.

There are three reasons why Zijin has taken the position it has, despite the fact that it will cause great displeasure in Port Moresby.

First, the PNG government’s Porgera decision damages Zijin’s 47.5% equity in the project, one of the company’s most important international investments.

Second, it must worry the operators of the Chinese government-owned Ramu Nickel Mine in PNG’s Madang province. The provincial governor, landowners and conservation groups have been agitating for some time for the Ramu mine to be closed on environmental grounds. As a consequence, the mine’s majority Chinese owners have deferred a $1 billion expansion.

The third reason is more complex, but equally important.

In November 2018, China sought to hijack the APEC Leaders’ Summit in Port Moresby. The summit was the largest international event ever held in PNG and one the Australian government provided substantial funding and administrative support for. Prime Minister Scott Morrison led a long overdue fightback.

Australia, New Zealand, the US, Japan and South Korea took a coordinated approach to help meet PNG’s significant infrastructure, economic security and social welfare needs with wider support for the island nations of the South Pacific. PNG’s prime minister at the time, Peter O’Neill, publicly embraced the approach, which included one of his pet projects, extending rural electrification throughout his country.

China’s intervention was effectively countered.

Since then, there has been a change of government in PNG. The new government has accepted a $380 million long-term soft loan from Australia. That has removed the need for a similar loan from China.

PNG is also negotiating a structural adjustment, fiscal management, and economic and social development program with donor agencies and nations. There are signs that this initiative will be even more multilateral than was first expected, with the World Bank now becoming involved.

The Chinese government may still have some involvement in the package, but its role seems to be significantly diminished.

China has provided some support for PNG to help meet the Covid-19 threat, but its support has been minor compared with that of Australia, which has responded comprehensively and generously.

So, is Australia’s robust Pacific step-up program, supported by other nations, mitigating China’s influence, at least at the national level?

It’s clear that China remains very active at the provincial and local government levels, especially on Bougainville, which, in itself, is a major concern.

But at the national level, its efforts appear to be more restrained, at least in the short term. There’s no doubt that the fallout from China’s behaviour at the APEC summit is a factor.

The positive impact that the step-up and the engagement of other countries is having on PNG can’t be discounted.

That should encourage the Australian government, even given our own difficult fiscal and economic circumstances, to ensure our development assistance program, and step-up, continue. Both need to be more focused than ever on enhancing our unique country-to-country and people-to-people engagement and our broader relationship.

And we need to encourage New Zealand, the US, Japan and South Korea to contribute to the overall program.

If the response to the Porgera mine nationalisation is a guide, it just might be that the step-up and related measures are having the right impact.

It’s early days, and China doesn’t appear to be lessening its activity elsewhere in the South Pacific, notably in Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Tonga and Samoa. But we might just be seeing the first positive signs that properly targeted programs delivered by Australia and its partners are having the desired effect.

The mine decision is very harmful to PNG’s international standing. One ratings agency has already downgraded its credit rating.

That will mean our assistance, if properly targeted and spent, is even more important than it is already. And when one looks at the critical state of the PNG budget, the economy, and social indicators, our help is desperately needed. It just has to be developed and delivered even more effectively.

This article is part of ASPI’s 2020 series on women, peace and security.

The Chinese government may have put up a facade of progress by signing international declarations and passing new laws, but the state of women’s rights in the People’s Republic of China remains unacceptable.

The latest unanimous resolution on women, peace and security adopted by the UN Security Council in October last year encourages member states to enable women ‘who protect and defend human rights’ to act in safe environments. This formulation of language was a compromise in the final draft, due to opposition from China and Russia to including a reference to ‘women human rights defenders’. Nonetheless, China reserved its position on the final paragraph.

The reason behind these tensions is clear. Women activists and human rights defenders have no freedom of action in China.

It was on 7 March 2015 that the face of Chinese feminism changed forever. That day, a group of feminist activists, later known as the Feminist Five, were arrested for demonstrating against sexual harassment.

Li Maizi, Wang Man, Wei Tingting, Wu Rongrong and Zheng Churan had been involved in women’s rights organisations for years and did not expect to be arrested, because the Chinese Communist Party claimed to be addressing the issues the women sought to highlight, which were not seen as politically sensitive.

Their plan was to hand out stickers on public transport in different cities on International Women’s Day. But authorities acted in advance, taking the five to a detention centre in Beijing the day before their demonstration.

The arrests attracted international attention both within and outside of the feminist community, and the ensuing backlash on social media is thought to have been what forced authorities to release the activists after 37 days of detention.

This happened 20 years after the UN’s Fourth World Conference on Women, held in 1995 in Beijing. On that occasion, 189 countries signed the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, pledging to fight for gender equality and to empower women by tackling poverty and violence and improving health and education outcomes.

It’s bitterly ironic that the country in which the international community passed such a fundamental milestone for global women’s rights has taken a drastic turn on the issue by cracking down on social movements and non-government organisations under the leadership of President Xi Jinping.

The CCP has since been undercutting any efforts by the Feminist Five and other activists to create safe spaces for women and raise issues of gender discrimination and domestic violence.

Despite the initial movement inspired by the five, feminist action in China has become unsustainable for many. One prominent example is the arrest in October of #MeToo activist Sophia Huang Xueqin, who had expressed her support for the Hong Kong protests.

But the Chinese feminist fight is far from over. Some activists have moved overseas in order to continue their work. This new, confrontational phase of the movement puts them at odds with the CCP, especially as restrictions imposed by the Great Firewall become harder to work around. The five, together with many other courageous women, keep working for their people, and ultimately their country, to protect the most vulnerable and address deep societal issues.

‘Women hold up half the sky’, proclaimed Mao Zedong. But in 2020, Chinese women are being repressed and subjugated. They lack political representation and live in a patriarchal society that emphasises traditional, Confucian values. This tendency harshly diminishes women’s public role, reducing them to instruments to be exploited for the benefit of the CCP and China’s economic prosperity.

The regime’s one-child policy, for example, has had far-reaching effects on women. Until it was withdrawn in 2015, the policy allowed for destructive practices that annihilated women’s freedom. The current push is for women to have more children in order to rebalance China’s ageing population. While their role as primary carers for elders and children remains, women are expected to study, work, pursue a career, get married and abide by unrealistic beauty standards. These expectations come while women are still subject to gender discrimination and abuse at home, on the streets, online and in the workplace.

The government is repressing activists because a broad feminist uprising would be a powerful voice against the CCP. By refusing to abide by traditional gender norms, women could threaten the stability of the authoritarian state, which relies on a patriarchal and deferential system.

As Chinese American author and activist Leta Hong Fincher wrote in a series of pieces, the Feminist Five had unique potential and gave life to a grassroots mobilisation not seen since the 1989 pro-democracy movement.

Countries that support gender equality, including Australia, should speak out on attacks against the defenders of human rights. If we all agree that women’s rights are human rights, something UN Secretary-General António Guterres has stressed, then when discussing the abuses taking place in China we must include women’s rights among those concerns.

The continued strength of the iron ore price is surprising, given the collapse of oil, which traders have recently been willing to pay buyers for if they’ll agree to offload full tankers.

Oil and iron ore are the two most basic commodities of industrial economies and, through much of their history, their prices have moved in tandem along with the underlying health of global industrial production.

But iron ore has been holding comfortably above US$80 a tonne throughout the Covid-19 crisis, delivering a continuing run of fabulous profits to Australia’s big miners, BHP, Rio Tinto and Fortescue, which can all dig it up at a cost of less than US$15 a tonne.

The current price is about 35% higher than the federal government expected when it cast its mid-year budget outlook last December.

The short explanation for iron ore’s strength is China. China buys almost three-quarters of all seaborne iron ore and is the dominant influence on prices. China is seen to have emerged from the public health crisis and there’s an expectation the government will respond to lingering weakness in its economy with public spending on infrastructure that will boost steel demand.

By contrast, China accounts for only around 14% of the global oil market, which has abruptly contracted. The International Energy Agency estimates oil demand globally will be down 6% this year, equivalent to subtracting India’s entire consumption.

With the Covid-19 crisis still acute across the major Western economies, it is too soon to know what the global economy will look like on the other side of it.

It may be that once social-distancing restrictions are eased, everyone will go back to eating at restaurants and then, once travel is allowed, resume their long-delayed holidays and business trips. It will all pass like a bad dream. A pointer in that direction is that cruise ship operator Carnival, which in many ways epitomises the reputational damage from the Covid-19 crisis, is taking bookings for ships departing Sydney in August.

But a more pessimistic scenario of a long-lasting downturn in global demand cannot be discounted. Unemployment will remain high, banks will face large debt write-offs and will be reluctant to lend, and companies will defer investment decisions.

The backlash against globalisation that has been building since the 2008 financial crisis may intensify, with the renewal of hostilities between the United States and China and pressure on companies to repatriate their supply lines. The World Trade Organization has forecast a fall in trade this year of anywhere from 13% to 32%. The post-Covid-19 world could be more like it was in the 1930s, when trade halved as a share of global GDP.

The resilience of the Chinese economy and its demand for commodities would be severely tested. The modernisation and development of the Chinese economy over the past 30 years has been driven by globalisation and the rapid growth of world trade. China has had some success in reducing its dependence on exports and fostering domestic consumption, but trade still underpins its manufacturing industry and it looks troubled.

In the first three months of the year, China’s exports to the US were down by 25% and its sales to the European Union were down 16%. Bigger falls are likely in the second quarter.

To some extent, the strength of the iron ore price relative to oil is a function of the leads and lags in the respective supply chains. Oil storage is limited and, if the producing nations keep pumping it at a faster rate than consumers are using it, the available space fills to the brim. The oil market is at that point.

By contrast, China’s manufacturers, construction companies, traders and producers all keep stocks of steel, and prices have been supported by buyers adding to inventories in anticipation of a revival in economic demand. The latest readings on Chinese industrial production for April show that, while businesses are slowly getting back to work, the loss of export markets is reducing overall output.

As is well understood, China’s appetite for Australian commodities has underwritten our prosperity for the past 16 years. The resource sector now accounts for almost a quarter of all business capital stock, double its share in 2004 when the great boom began.

This has made Australia the pre-eminent supplier of mineral and energy resources to the world. The high cost of Australian labour has been more than offset by the world-beating efficiency of our resource companies, by the intrinsic quality of the reserves they exploit and by the strength of Australian governance. Those attributes have been rewarded with prices that have been higher for longer than at any point in Australia’s history.

An economic variable that has a big impact on living standards is the ‘terms of trade’, or the prices we receive for our exports versus the prices we pay for our imports.

During the technology boom of the late 1990s, the prevailing wisdom was that Australia had backed the wrong horse: the technology we imported would go up in value while the resources we exported would go down. As treasurer, Peter Costello was advised to subsidise the construction of an Australian microchip plant to shift the balance.

But the China-led resource boom meant that the average price for Australia’s exports since 2004 has been about 60% higher relative to the average cost of imports than was the case over the preceding 20 years. This has helped to sustain strong growth in living standards in Australia despite relatively poor productivity.

The long-term history—and there’s good data going back to the 1870s—is that booms in the terms of trade are followed by busts. Export prices drop well below their long-term average (relative to import prices) before returning to it.

Reserve Bank of Australia analysis of terms of trade booms and busts over the past 150 years shows that downturns are associated with weak per capita income growth and high unemployment and that it’s typically around five years before income growth recovers.

While the future is in flux, policymakers should be considering this as one of the potential outcomes from the crisis.

One point that should be made is that a sustained fall in iron ore prices would not be accompanied by a reduction in China’s demand for Australian supplies, which have the lowest production costs. In any commodity, prices will only fall as the highest cost producers are knocked out of the market. In iron ore, the highest cost producers are China’s own.

If China’s demand falls, it will be China’s iron ore mines that are rendered uneconomic and forced to close, while its dependence on seaborne trade will increase.

Covid-19 and China challenge Australia in the South Pacific.

Add in the category-five severe tropical cyclone that’s just pounded Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Fiji and Tonga.

The pandemic and the aftermath of Cyclone Harold constitute the immediate crisis. China is the long-term test of power and governance in the islands.

From different directions, the issues of pandemic, cyclone and power ask Australia questions about its interests, influence and values in the South Pacific.

Dissimilar questions throw up a similar answer: Australia must put Pacific people at the centre of its South Pacific policy.

As my previous column argued, this simple statement sits atop much complexity. Embracing this seemingly obvious idea would open many new thoughts about the future place of Melanesians in Australia, alongside the traditional interests of Australia in Melanesia.

Put Pacific people at the centre of our policy by emphasising all the positives in the islands. Yep, plenty of positives! No Pacific lament here.

The peoples of the South Pacific—inhabiting an environment which can be as harsh as it is beautiful—constitute true nations. The island nations have clear identities of culture, language, ethnicity and history, offering much to admire and learn from.

The islands have strong societies—even though their states are weak—and made the smoothest transition from colony to independence of any region.

Without exception, South Pacific states have been able to transplant and grow Western democratic forms, a better collective record than anywhere else in the developing world. Fiji proves the power of the Pacific’s democratic norm by clawing its way back to elections from its military coups.

Pacific democracy is beset by ‘big man’ politics and corruption, but democracy reigns across the region—often rough, yet admirably robust. The next challenge is for Pacific women to get their share of political power.

Now consider the positives that are central to Pacific life. The islands are Christian with relatively conservative societies that are English-speaking, pro-Western and pro-capitalist. Apart from English as the lingua franca, the French territories of Polynesia, New Caledonia and the Loyalty Islands also tick those boxes.

The flippant version of all this is that Australia embraces the place everybody else in the world wants to visit on holiday. The lucky country lucks out again—we get to do institution-building in paradise.

The serious version is to add up all those positives: strong both societally and culturally, democratic, pro-Western and conservative.

No wonder Australia is the region’s status quo power. Scott Morrison’s inspired embrace of the ‘Pacific family’ is about shared values as well as Oz interests. Canberra’s job is to accentuate those Pacific positives, to work with what’s natural in the islands.

The six reviews and inquiries Australia is conducting on the South Pacific will build on long history and deep policy knowledge. And beyond the usual discussion of aid, defence, trade and investment, two of parliament’s inquiries are about Pacific people—the human rights of women and girls in the Pacific and strengthening relationships via the Pacific diaspora, ensuring the Oz step-up reflects ‘the priority needs of the governments and people of Pacific island countries’.

Australia, surely, is set to abandon the budget trajectory of the past five years that saw deep cuts in foreign assistance. Time to start pumping lots more money into aid, showcasing Canberra’s recent amazing ability for screeching policy turns, junking long-held views.

An aid U-turn and lots more bucks for the South Pacific is a big policy shift; yet the really hard part will be philosophy and focus. That is where putting Pacific people at the very heart of policy matters.

Australia has a proud history of helping the islands with health and education. Time to power up that history and do much, much more. More money. More focus. More people. The story Covid-19 is telling about island health systems has a sad parallel in education, especially in Melanesia.

The people dimension can drive Australian responses to the China challenge. Kevin Rudd is right to note, ‘If we want to be the partner of choice, we need to also acknowledge we are not the only choice of partner.’ China will have a big role. Our aim must be to work with the islands and key institutions to shape that role.

Canberra has dealt itself into China’s island game by creating the A$2 billion Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific, to be managed by the Office of the Pacific within the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The high-priority list includes telecommunications, energy, transport, water and other essential infrastructure. There’s lots of room for China to play, though, with the region needing US$3.1 billion in investment each year to 2030.

Playing to our strengths and the values of Pacific people can write the script for playing with, not against, China. Important institutions can do much to shape that script: the Pacific Islands Forum, the Pacific Community, the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank.

An equation that says China does infrastructure while Australia serves Pacific people is a winner. Take heart from Richard Herr’s conclusion that ‘China’s current regional soft power lacks breadth and depth’.

The South Pacific positives lean towards Australia, not China. Time for Australia to lean in to help Pacific people.

As the novel coronavirus has spread from its original epicentre of Wuhan into a global pandemic, China’s ruling communist party is pushing a new narrative.

After some initial missteps by local officials, this narrative goes, the central government took charge and defeated the virus with tough, resolute measures. Western countries are now suffering because of their lax response and the inferiority of their cacophonous democratic systems compared with China’s one-party model. Other countries should learn from China’s success, and the Middle Kingdom is now generously sending expertise and badly needed equipment to the hardest hit places. China’s healthcare workers are heroes. And by the way, the virus may actually have originated with the US military, not in China.

It’s a message being slavishly promoted in the party-controlled state media, parroted by Chinese diplomats around the world, and perhaps even believed by a significant percentage of Chinese citizens subjected to decades of brainwashing by relentless propaganda and an education and indoctrination system that extols the virtues of party rule.

But around the world, this narrative is being met with derision and outright hostility.

The alternative narrative, gaining increasing currency, is that China’s central leadership in Beijing knew early on about the severity and extent of the mysterious new virus in Wuhan and lied to the world in a massive cover-up. In those early crucial days, China barred experts from the World Health Organization and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. President Xi Jinping received a grim assessment on 14 January about the Wuhan virus becoming a pandemic, according to reporting by the Associated Press, but the public was not warned until a week later. The late January lockdown of Wuhan came far too late, after more than half the city’s 11 million residents were allowed to leave for the Lunar New Year holiday.

Even now, according to this view, China’s leaders continue to lie and to obfuscate. Many believe China’s death toll from Covid-19 is far higher than the country is willing to admit, and that people with virus symptoms are simply no longer being tested. Most new infections are being blamed on ‘imported’ cases from abroad, even though the vast majority are Chinese nationals returning home from overseas.

The deliberate implication is that foreigners are now carrying the virus, stoking Chinese nationalism, xenophobia and racism, evidenced by the sickening scenes of Africans in Guangzhou being forced from their apartments or locked into forced quarantine. Some restaurants, including McDonald’s, displayed signs saying black people would not be allowed inside.

The coronavirus controversy, and Chinese diplomats’ ham-handed triumphalist tone, now threaten to disrupt the world’s relationship with China for years to come, long after the immediate crisis has abated. The country’s carefully cultivated global image, backed by huge infrastructure projects like its Belt and Road Initiative, will take a heavy blow.

Leaders of countries long friendly to China because of economic concerns—and willing to turn a blind eye to its atrocious human rights record and abuses like holding a million Muslim Uyghurs in concentration camps—are demanding Beijing be held to account.

Australia’s foreign minister, Marise Payne, called for an independent investigation into the Chinese origins of the virus and how it spread. German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron called on China to be transparent about the virus.

In the US, President Donald Trump, already embroiled in a trade war with China, hinted the virus may have been spread purposefully while calling for a probe. ‘If it was a mistake, a mistake is a mistake. But if they were knowingly responsible, yeah, then, sure, there should be consequences’, Trump said. He had earlier announced a suspension of US funds to the WHO pending an investigation of its dealing with the early stages of the outbreak, when officials praised China’s response and advised against travel restrictions.

In Africa, Obiageli ‘Oby’ Ezekwesili, a former vice president for Africa for the World Bank and a former Nigerian cabinet minister, wrote an op-ed in the Washington Post demanding China pay compensation to African countries for the virus, including a complete write-off of US$140 billion in debt. ‘China should demonstrate world leadership by acknowledging its failure to be transparent on Covid-19’, she wrote.

This came after several African foreign ministers summoned the Chinese ambassadors in their countries to decry the inhumane treatment meted out to black Africans in Guangzhou, something that prompted a tough video rebuke to Xi from a former African Union ambassador to the US and a warning from the State Department to black Americans to avoid Guangzhou.

China has spent decades and billions of dollars developing its ties with Africa, and the hard work of that dollar diplomacy now seems upended by a virus.

Meanwhile in the US, the state of Missouri filed the first lawsuit in federal court against the Chinese government, accusing Beijing’s leaders of an ‘appalling campaign of deceit, concealment, misfeasance, and inaction’ over the coronavirus and claiming Chinese officials are ‘responsible for the enormous death, suffering, and economic losses they inflicted on the world’. Two Republican members of Congress have introduced legislation making it easier for private American citizens to file suits against China for deaths and economic hardship unleashed by the virus.

All of this comes without any evidence so far that the virus may have accidentally emerged from a virology laboratory in Wuhan, a suspicion initially embraced by conspiracy theorists.

Chinese officials have deflected the finger-pointing, blaming others for trying to ‘politicise’ the crisis and insisting that Covid-19 is a scientific and medical issue best left to the experts.

Beyond the blame game, the coronavirus crisis is likely to reorder global supply chains to China’s detriment. When China first began its lockdowns in January, multinationals—from South Korean car companies to American toy makers—were forced to halt or delay production because they relied on crucial components or parts from mainland Chinese factories. Many will not want to again be caught so dependent.

Countries worldwide now will become more cautious about allowing China to be their chief supplier of medical equipment like facemasks and pharmaceuticals. In the past, globalisation’s mantra was ‘build it where it’s cheapest’, and most often that was China. But post-Covid-19, for crucial medical supplies, the new motto is likely to be, ‘make it at home’.

There is little doubt the world is set for a reordering whenever the pandemic finally fades. China would like it to be one on its own terms, in the absence of American global leadership, where the country’s leaders can showcase the superiority of their authoritarian model.

But what seems more likely is a new world order with China increasingly cast as an international pariah, a regime that placed its own pride and prestige over transparency about a pending pandemic. The communist party’s cover-ups, suppression of information and dissemination of disinformation will likely have cost hundreds of thousands of lives and plunged the world into a colossal global recession. And its xenophobia and racism have been laid bare.

The virus will eventually be contained, either through a vaccine or more widespread infection that eventually builds herd immunity. But in the world’s post-pandemic relations with China, it will no longer be business as usual.

The global economy may be in hibernation, but geopolitics is thriving and sprinting towards a potential crisis at the end of this year or early in 2021. The immediate and understandable focus is on fighting the virus, but our government needs to be thinking about defence and national security risks as well.

The core of the security problem is the Chinese Communist Party’s drive to emerge from the Covid-19 pandemic strategically stronger in the Asia–Pacific than the US and its allies.

This is not just about diplomacy. The Chinese military is aggressively positioning around Taiwan, using ships and combat aircraft to push into Japanese and South Korean territory and doing high-end combat training in the South China Sea.

At the same time, Chinese state media outlets are fomenting aggressive nationalism. The Global Times, the party’s English-language paper, editorialised on 4 April: ‘If the Taiwan question leads to a China–US showdown, no matter what the results, Taiwan will pay an unbearable price … The world has entered an eventful period, during which Taiwan is ineligible to play an active role.’

Beijing’s sabre-rattling over Taiwan is hardly new, but in the first months of 2020 we’ve seen a significant stepping up of Chinese military activity and an intense propaganda effort to isolate Taiwan and assert political primacy in the region.

Forget the conspiracy theory that Covid-19 came from a People’s Liberation Army biological warfare laboratory. That’s fantasy. What is fact is that Beijing is using the virus to position itself as the saviour of much of the world, sending medical equipment and doctors, building political indebtedness and loudly claiming that authoritarianism is doing a better job of beating the virus than Western democracy.

This is why there’s such an intense CCP push to win the narrative battle. And it’s why there’s such hostility to self-evident judgements that the virus originated in China and that the party hid the seriousness of the crisis in January while Chinese companies stripped other countries of protective medical equipment.

Here’s an example: Greenland Australia, a Sydney-based, Chinese-owned property development company, has admitted that ‘in late January and early February’ it was directed by its Shanghai-based parent to buy and ship massive quantities of medical supplies from Australia to China.

While this was happening, on 30 January, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi spoke with Australian Foreign Minister Marise Payne. Wang told Payne, ‘The epidemic is generally preventable, controllable and curable.’ On 13 February, the Chinese embassy in Canberra was expressing ‘deep regret and dissatisfaction’ over Australian restrictions on travel from China, saying these were ‘extreme measures, which are overreaction indeed’.

The CCP’s strategy during the crisis has been to extract maximum advantage for itself at the expense of every other country.

The Global Times reported that PLA combat aircraft for the first time conducted night-time combat drills southwest of Taiwan on 16 March. The paper said, ‘Similar drills are expected to become more frequent in order to let Taiwan secessionists get a clear idea of the power gap between the mainland and the island’.

On 20 March, a Chinese fishing boat collided with the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force destroyer Shimakaze in the East China Sea. Japan claimed the incident occurred in international waters, while Beijing said it was in Chinese coastal waters.

On 26 March, South Korean jets were scrambled to intercept Chinese surveillance aircraft that flew into Korean-claimed airspace.

In the South China Sea in the middle of last month, the PLA Navy’s first aircraft carrier, the Liaoning, conducted flight training. The PLA Daily said, ‘Training for war preparedness will not be stopped even in the middle of the COVID-19 epidemic, and the training of carrier-based fighter pilots must continue.’

The Liaoning is still operating in the South China Sea. For its part, the US Navy last week sent a guided missile destroyer, USS Barry, through the Taiwan Strait—a transit intensely disliked by Beijing—and the amphibious assault ship USS America exercised with the Japanese warship Akebono.

This heightened level of military exercising has gone largely unnoticed because of Covid-19. While it’s not unprecedented, at this time of international crisis there’s a risk that the PLA’s posturing could spark a conflict.

Beijing’s increased military activities are meant to be seen as a show of strength and to contrast with the challenges the US Navy is facing with maintaining a viable presence in the western Pacific. The aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt has been tied up in Guam since Covid-19 infected many of its crew. China claims that three other American aircraft carriers have Covid-19 outbreaks and that there’s currently no viable US carrier presence in the Pacific.

It’s unlikely the PLA has been able to avoid some Covid-19 infections, particularly among those soldiers used as first responders in Wuhan, but by not revealing the early stages of the crisis China had more time to quarantine elite units.

Beijing is clearly showing it can operate forces around the so-called first island chain that includes Japan, Taiwan and maritime Southeast Asia.

How might this play out across the rest of this year and into next year? I anticipate a dangerous situation arising over Taiwan as President Xi Jinping seeks to seize a strategic advantage while the US remains dangerously incapacitated.

A scenario could look like this: Xi has shaped his premiership around preparing for two critical centenaries. The 100th anniversary of the founding of the CCP is on 21 July next year, at which time Xi’s aspiration is for China to be ‘moderately well off’. By October 2049, the centenary of the party’s takeover of power, China is to be a ‘strong democratic, civilised, harmonious and modern socialist country’.

Xi likely won’t be around in 2049, but he will steer the party through next year’s anniversary. Covid-19’s effect will be to damage the aspiration of being moderately well off. Xi may calculate that now is the moment to harness Chinese nationalism by focusing the population on a campaign to retake Taiwan.

Militarily, the calculation may be that the US is distracted by Covid-19, President Donald Trump’s failure to manage it and an election campaign. With the virus reducing Western military effectiveness, there may not be a better time for the PLA to blockade the Taiwan Strait and economically squeeze Taipei.

Taiwan is now a successful liberal democracy. It has shown how to manage a Covid-19 lockdown without resorting to the repressive measures seen in Wuhan. The Taiwanese have never seemed less inclined to support so-called unification with the mainland. Being a different and successful model of political organisation, Taiwan profoundly threatens Xi’s personal leadership and the CCP’s credibility.

A crisis over the Taiwan Strait would instantly push the region into a dangerous cold-war situation, one that would be the ultimate test of US credibility as a Pacific power, and would existentially threaten Taiwan and Japan. There would be no guarantees that a blockade wouldn’t slide into major and sustained conflict, drawing in the US and its allies.

A pre-emptive effort to coerce Taiwan would be immensely risky for Xi, but leaders under pressure do risky things, and Beijing has a long history of pushing the limits of regional tolerance—as with island-building in the South China Sea—to see what it can get away with. The challenge for Washington, Canberra and other allies and partners is to ensure that Xi calculates that this is a risk not worth taking.

What should Australia do? First, Prime Minister Scott Morrison needs to talk with Trump, his Japanese counterpart Shinzo Abe, Indonesian President Joko Widodo, a recovered UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson and any other national leader who is willing to join a coordinated push-back against Chinese military opportunism.

This is a tough call. Canberra’s deepest instinct is to say nothing and hope all will return to justin-time normality. That won’t happen. Covid-19 exposes the real nature of the CCP, which cannot be accommodated by an Australia that needs to build up practical sovereign capabilities to ensure national security.

Second, far from thinking that this is a time to cut defence spending, the government needs to double down on strengthening the Australian Defence Force, including by urgently building up ammunition and fuel stocks to have the force as operationally ready as it can be.

Australia is going to be deeply in debt, but we don’t have to be in debt and insecure. Now is the time to invest in nation-building, sovereignty-enhancing defence capabilities. A defence budget closer to the US’s 3.2% of GDP rather than just under 2% would be a more realistic base from which to deal with the strategic risks we face.

Third, it’s time for new thinking about our national security challenges. For unworthy bureaucratic reasons, we did away with a national security adviser years ago and haven’t seen a national security strategy since 2013, when Prime Minister Julia Gillard produced a flabbergasting document that said Australia faced a ‘positive’ and ‘benign’ security outlook.

Fourth, a new defence white paper must be commissioned soon. At Minister Linda Reynolds’s direction, the Defence Department has been working on a strategic update and review of procurement plans. But that was before Covid-19. We’ll need something that’s dramatically bigger and produced much faster than the 2016 white paper, which took two years to develop—the time it took China to build three air bases in the South China Sea.

Finally, Morrison has wisely realised that Covid-19 will force Australia to redesign its approach to supply chain security. A stronger national security perspective must be brought to how we manage the supply of fuel, food, medical equipment, information technology and critical infrastructure. This will unseat many comfortable Canberra assumptions, but there is no return to the pre-Covid-19 world.

Covid-19 is changing everything and turbocharging the strategic trends that were already making the Indo-Pacific region a riskier place. The reality of China’s threat to regional security is undeniable. Now we must prepare for the crisis after the crisis.

Beijing is declaring success in its control of Covid-19. It’s a funny kind of success, though, because on closer examination it looks more like what Australia, Taiwan, South Korea and New Zealand are doing now.

What we would call ‘lockdown’ is still in place across much of the country.

In a country of 1.4 billion people, the Chinese government’s reported number of Covid-19 cases is 83,403, a figure which has pretty much flatlined since late February. That’s less than 0.006% of the Chinese population.

If you believe these official figures, then 99.994% of China’s population is still at risk of infection (not counting under-reported and unknown asymptomatic cases).

In comparison, Australia’s 6,462 cases make up 0.026% of our population, so 99.974% of our population is still at risk of infection. Our prime minister and chief medical officer are looking at ways to open some things up very slowly, but they’re not about to reopen the economy based on these figures. They can’t unless they want a pandemic that overwhelms our health system.

In China too, without a vaccine or way to control the spread of the virus other than tight physical lockdowns, the epidemic will simply accelerate through other parts of the country.

This pandemic started with a single infection in a wet market in Wuhan. It could get out of control again if just one infected individual slipped through Beijing’s control measures. Asymptomatic cases mean this is very likely to happen if controls are really lifted in meaningful ways.

So, any idea that the Chinese Communist Party has triumphed over Covid-19 is sadly wrong.

The only way China can get chunks of its economy back to business is by maintaining constraints on people’s movement or by sacrificing people’s health and lives in pursuit of production. That second path would mean tolerating outbreaks and the deaths they bring, which would be a cynical move demonstrating that the regime valued power and perceived success over the lives of its people.

Chinese officials were told by the party that in the ‘people’s war’ against Covid-19, rising infection numbers in their province or city would be a sign of failure. Since then, the official numbers across the country have fallen remarkably, with many areas now reporting no new cases.

Some of this is driven by ruthless suppression measures that are what we all know now as social distancing—although in China’s authoritarian system, that includes security personnel in hazmat suits whacking people with batons and dragging them into vans, as well as welding people into their apartments.

Remember, though, that it was local officials in Wuhan who supressed early reporting of cases, so it’s not a shock to see under-reporting of cases, given the pressure from the top.

The CCP is also setting the scene to blame foreigners coming into China for any second wave of infections, rather than the more likely source—community transmission within China itself.

Under the headlines touting President Xi Jinping’s success, we see a different story. A spokesperson for Beijing’s municipal government has announced that ‘epidemic control and prevention will probably become a long-term normal’ in China’s capital.

Beijing has become a biohazard fortress protected against its own citizens and against foreigners flying in—as we saw in footage of a UK Sky News crew returning to Beijing recently.

And Chinese authorities are putting out guidance like ‘3 tips for restaurants’: develop new menus for individual diners, sell food and vegetables online, offer takeaway.

None of this sounds like the economy is back to anything like business as usual.

In Wuhan itself, success looks a long way away, despite the central government’s announcement of the end of the lockdown there, during a curated tour of senior leaders, all wearing masks.

Tall barriers surround many housing compounds. Some people in ‘epidemic free’ residential compounds are now being allowed to leave their homes for up to two hours a day. Schools and universities are still closed; masks, temperature checks and identity checks are mandatory; and the city is sprinkled with ‘front line prevention and control positions’. Some travel in and out of Hubei province will now be permitted, but with rigorous checks on a tightly controlled number of travellers.

The measures in place in Wuhan look tighter than those in Australia—and they’re almost certain to remain so until a vaccine can be developed and rolled out.

Why the propaganda and the pretence?

The CCP wants to create the picture that China is managing the epidemic better than anyone else.

That’s for two reasons, one domestic and one strategic.

Domestically, the party needs the Chinese people to believe that it’s doing a great job, to get past the nasty truth that party mismanagement and repression let the virus spiral out of control first in China and then globally. The party also needs to the Chinese people to believe that only its rule can protect them.

Strategically, Xi’s success narrative is all about contrasting China with the US: authoritarianism is good, democracy is bad and weak. If it can deceive the world with this false narrative, Beijing thinks it can gain global power and influence.

As with all narratives, there has to be at least a tenuous connection to reality; it is true that the US isn’t managing the epidemic well.

Unfortunately for the party’s narrative, however, there is a global best practice beacon of governance and Covid-19 control in North Asia—and it’s not on mainland China. It’s the democracy of Taiwan, which, with a population about the size of Australia’s, has 395 confirmed cases and 6 deaths.

Taiwan shows that global best practice for pandemic control doesn’t come from Xi’s authoritarian regime but from a true ‘democracy with Chinese characteristics’.

That’s a confronting truth that is just not reportable or even sayable in mainland China.

Other best practice countries are South Korea, New Zealand and Australia. And, like Taiwan, we’ve been able to get our populations’ cooperation without government thugs hitting them with batons or welding apartment doors shut.

That’s the narrative—and the truth—the world needs to hear, including the 1.4 billion Chinese citizens living under party rule.

The Chinese Communist Party is notorious for obscuring how it runs the government of the People’s Republic of China. Its defence budget is particularly murky, earning a measly 1.5 (on a 12-point scale) from Transparency International UK. For reference, New Zealand’s defence budget was assessed at 12 and the US’s at 11.

There are only two sources of information on the PRC’s military expenditure: the United Nations’ military spending database and the PRC’s most recent defence white paper. The former presents reported expenditures from 2006 to 2013. The latter covers the same information from 2010 to 2017. These are big-picture numbers only. Unlike, for example, the United States defence budget, which anyone with a computer can bore down 10 layers into and find the unit price for an M-4 carbine, no similar information exists for China’s expenditure.

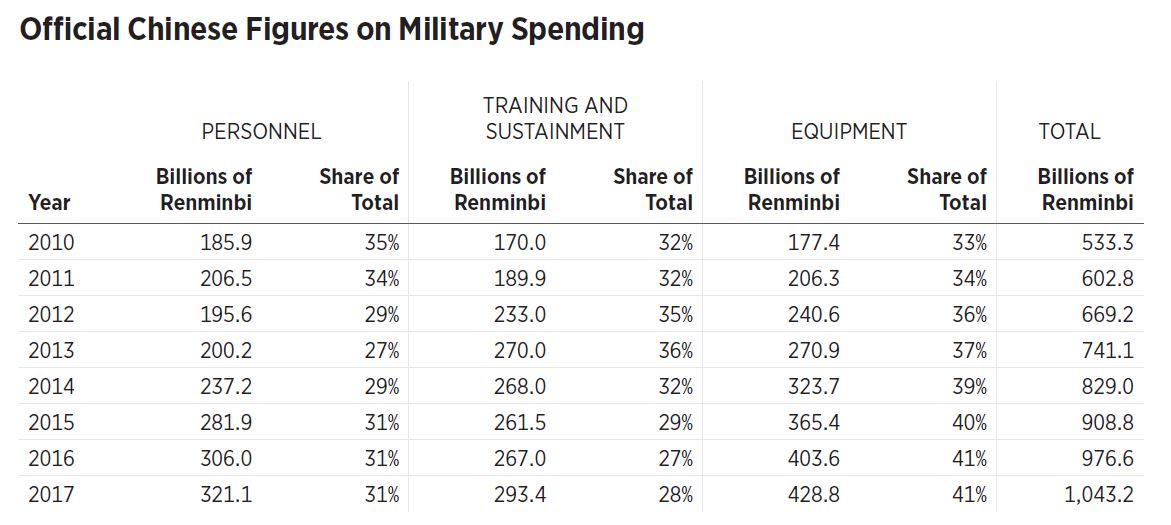

The defence budget data available from Beijing, reproduced in the table below, suffer from three distinct problems: lack of transparency, known omissions and unreliability.

Source: State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, China’s national defense in the new era, Foreign Languages Press, 2019, p. 39, accessed 12 February 2020.

Source: State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, China’s national defense in the new era, Foreign Languages Press, 2019, p. 39, accessed 12 February 2020.

The data are not very revealing. There are only three big accounts: personnel; training and sustainment; and equipment. And none of the resources are allocated according to service branch, so we can’t see how much of the personnel funds are devoted to the People’s Liberation Army ground forces versus the PLA Rocket Force.

There are also no reported resources dedicated to research and development. This is the largest known omission in the reported budget. The PLA frequently deploys and parades new weapons. They had to be researched and developed somewhere. Adding to the murkiness is Beijing’s embrace of military–civil fusion, which makes it extremely challenging to separate civilian from military R&D.

Other glaring omissions in the PRC’s defence budget are allocations needed to support the People’s Armed Police (now under control of the CCP’s Central Military Commission), foreign weapons procurement, and the subsidies given to state-owned enterprises performing military work.

Neither the UN reporting website nor the white paper has a lot of historical data, starting in 2006 and 2010 respectively. And neither data series is updated to the present, much less able to provide insight as to future plans. Projections based on such limited and unreliable data are but little better than guesswork.

Here’s another problem: the data are reported in billions of yuan, since UN reports are filed with local currency. Distortions arise in any currency conversion, adding to the challenge of understanding what the Chinese numbers mean in nation-to-nation comparisons or in the global context.

The West and its academic community must find a way to overcome all of these challenges if we are to get a clear understanding of PLA military expenditures. There were substantial efforts earlier in the decade, but they have largely dried up.

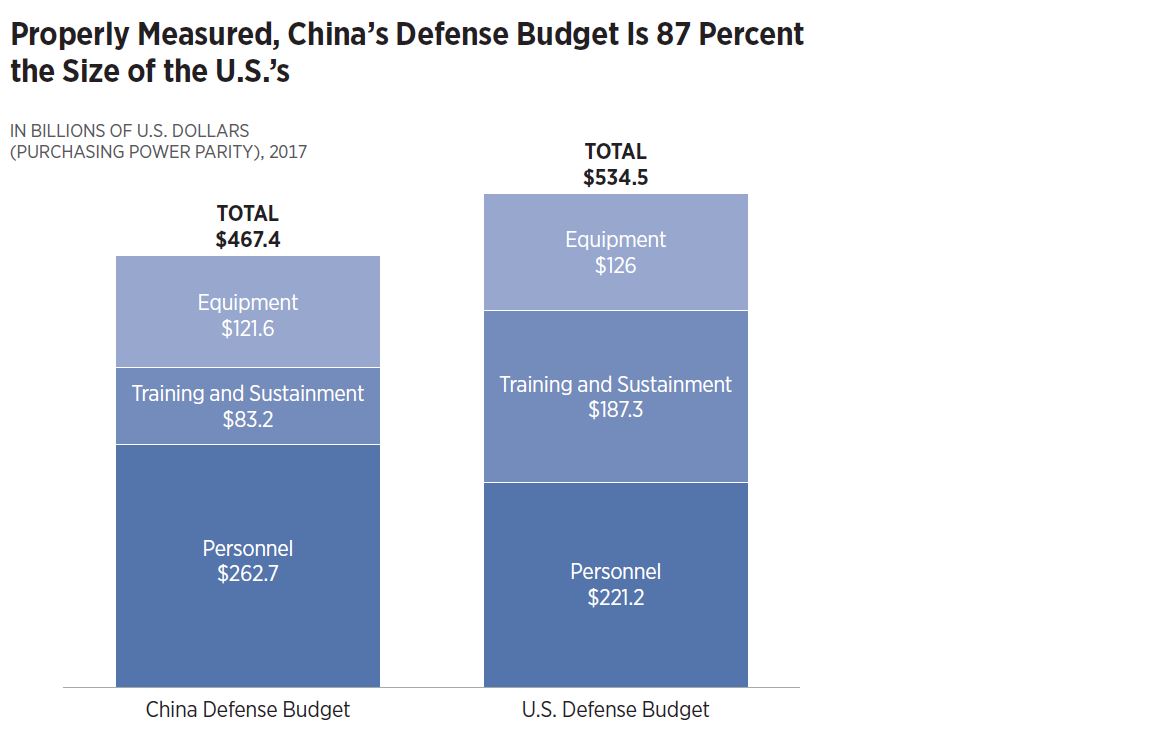

I have taken a shot at comparing how the PRC’s defence budget compares with that of the US. When comparing the two, my goal was to put the US budget in the level of fidelity of the PLA’s. For example, I removed US R&D costs and moved its civilian personnel costs to the personnel account. After those adjustments, the main task was to properly adjust the yuan values to US dollars.

On equipment, training and sustainment values, I used purchasing power parity to give a more equitable comparison. To adjust personnel costs, I compared salaries of all US government workers with those in the PRC to get a multiplier that would make personnel costs equitable.

With those adjustments made to data from the 2017 budgets (the most recent available from the PRC), the PRC’s defence budget accounts for 87.45% of the American purchasing power. This comparison excludes research and development costs. Moreover, because my methodology emphasises the differences in labour costs, it necessarily favours the PRC’s market. The results are displayed in the chart below.

Sources: Author’s calculations based on data accessed on 24 January 2020 from World Bank, ‘PPP conversion factor, GDP (LCU per international $)—China’, 1990–2018; National Bureau of Statistics of China, ‘Indicators: employment and wages: average wage of employed persons in state-owned units (yuan)’, 2009–2018; US Bureau of Economic Analysis, ‘Wages and salaries per full-time equivalent employee by industry’, 2011 to 2018; State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, China’s national defense in the new era, Foreign Languages Press, 2019, p. 39; Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), National defense budget estimates for FY2020, US Department of Defense, May 2019.

Sources: Author’s calculations based on data accessed on 24 January 2020 from World Bank, ‘PPP conversion factor, GDP (LCU per international $)—China’, 1990–2018; National Bureau of Statistics of China, ‘Indicators: employment and wages: average wage of employed persons in state-owned units (yuan)’, 2009–2018; US Bureau of Economic Analysis, ‘Wages and salaries per full-time equivalent employee by industry’, 2011 to 2018; State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, China’s national defense in the new era, Foreign Languages Press, 2019, p. 39; Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), National defense budget estimates for FY2020, US Department of Defense, May 2019.

Despite its limitations, this comparison should at least draw attention to the gaps in our knowledge of PRC military expenditures. During the Cold War, the US had divisions in multiple intelligence organisations dedicated to understanding the Soviet Union’s military expenditures. That’s not happening with China. Today, Washington’s two authoritative sources on this topic, the US–China Economic and Security Review Commission’s 2019 annual report and the Defense Intelligence Agency’s China military power, dedicated a combined total of five pages to the PRC’s defence budget. Neither report provides any methodological justification for the independent estimates.

The 2017 US national security strategy acknowledges that we have returned to an era of great-power competition. In such an era, understanding what your competitors are doing is essential. Knowing how much your competitors are dedicating to defence is one small part of the puzzle—but it’s an important piece, and one that is currently severely neglected.

We must dedicate more to this discussion if we are to fully understand what the CCP is doing internationally and how the PLA is evolving.