Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

In this episode, ASPI’s Genevieve Feely speaks to gender equality and social inclusion expert Amy Haddad about multilateralism to mark the 75th anniversary of the UN. They discuss the challenges the organisation faces, opportunities for reform, and changes in gender representation at the UN.

Next, Jake Wallis and Samantha Hoffman from ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre discuss their report, Retweeting through the Great Firewall, and how they went about analysing 170,000 Twitter accounts to uncover an influence operation targeting Chinese-speaking communities outside of mainland China.

And finally, ASPI’s Graeme Dobell and historian Peter Edwards discuss the evolution of Australia’s intelligence agencies and why, following the establishment of the home affairs portfolio, there should be an inquiry into the intelligence agencies similar to those conducted by Justice Robert Hope in the 1970s and 1980s.

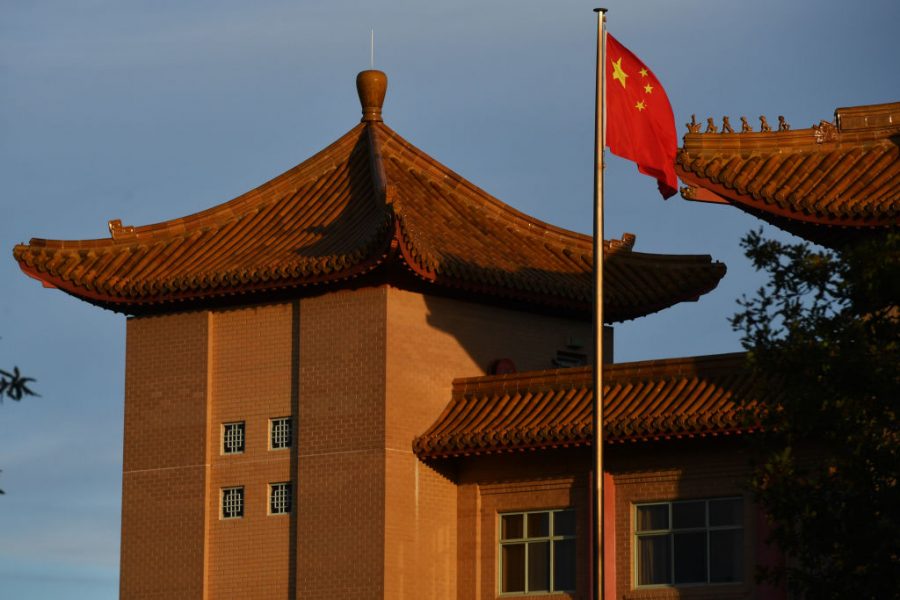

Hong Kong’s first handover to China, in 1997, came with fireworks, lion dances and a mood of cautious optimism that this former British colony would enjoy ‘a high degree of autonomy’ for at least the next 50 years.

Just 23 years later, Hong Kong’s second handover to China—punctuated by a draconian new national security law that proscribes much protest activity and free expression—has seen fearful citizens deleting their Twitter accounts, political parties disbanding, and some activists and ordinary people planning to flee abroad. The optimism of 1997 has been replaced by a sense of foreboding and dread.

In a fitting coda, Beijing’s Communist Party rulers chose the exact anniversary of the handover, midnight on 30 June, to impose their new security law on Hong Kong and unveil its strictures on an unwilling population. After 23 years, China seems to be publicly affirming that the ‘one country, two systems’ experiment has failed and that Hongkongers were not sufficiently imbued with a patriotic love of the motherland and its authoritarian communist one-party system.

Now Hongkongers who had enjoyed a wide range of freedoms and a tiny taste of democracy will be subjected to the same sweeping constraints on their liberties as any Chinese citizen living on the mainland.

Over the past month, the new national security law was drafted behind closed doors in Beijing with no input from Hong Kong officials or citizens, who were not even allowed to see the text until a few minutes before midnight on the day it took effect. There was still some small hope that the law might not be as sweeping as some here feared, perhaps tailor-made for Hong Kong owing to this city’s special history and common-law traditions. Various leaks in the media in recent days appeared designed to assure people that their daily lives would not be greatly affected.

But the final text of the law was more severe and more detailed than the most optimistic here envisaged. Many when they saw it were aghast—shocked, they said, but not surprised.

The law establishes an entirely new infrastructure in Hong Kong to enforce a national security regime. Beijing will set up a national security agency in Hong Kong which will operate independently as it sees fit. China’s agents operating here, with special ID cards, and their cars, ‘shall not be subject to inspection, search or detention’ by local Hong Kong police. They are above the law.

Hong Kong will set up its own separate national security committee, chaired by the chief executive and including a ‘national security adviser’ appointed by Beijing. Its work will remain secret and not subject to judicial review. The law specifies that Beijing’s national security adviser will attend meetings of the committee.

The Hong Kong Police Force will establish its own national security department to collect intelligence and conduct operations. The law gives police wide powers to conduct searches, eavesdropping and surveillance without court oversight and to order people to turn over their electronic communications, and it appears to suggest that internet service providers must cooperate with probes. The law compels suspects to ‘answer questions’ and turn over information, although Hong Kong law gives people a right to stay silent.

The law also says that when there’s a conflict between this new edict and Hong Kong’s existing laws, the national security law takes precedence.

The law sets up a new section in the Justice Department to prosecute national security cases, and trials can be conducted entirely in secret, without a jury, and without the presumption of bail. Serious or ‘complex’ cases can be tried in mainland China.

The law says the Hong Kong government will ‘strengthen public communication, guidance, supervision and regulation’ of national security matters, including those relating to ‘schools, universities, social organisations, the media, and the internet.’

The law vaguely defines four categories of national security offences—secession, subversion of state power, terrorism and collusion with a foreign country. Appearing in Washington DC to advocate for sanctions against Hong Kong or ‘provoking hatred towards the central government’ are all now considered national security law violations.

Penalties for national security offences range up to life imprisonment, although a person who ‘conspires’ with a foreign country ‘shall be liable to a more severe penalty’.’ The Hong Kong justice secretary told a press conference on 1 July that if a suspect were handed over to mainland authorities to face trial, Hong Kong would have no say in whether the death penalty was imposed.

In a sweeping claim of extraterritoriality, the law also says it will cover offences ‘from outside the region by a person who is not a permanent resident of the region’.

The vagaries of the law for now leave it to the local Hong Kong police to interpret and enforce it. Their actions on 1 July—the handover anniversary when activists traditionally stage mass protest rallies—showed the police are taking an expansive view, arresting people for carrying flags promoting Hong Kong independence.

Police raised banners warning demonstrators that chanting the slogans and displaying the flags that had become a staple of the last 12 months of protest could now be considered a national security violation.

‘The law is so broadly written it could include almost any form of behaviour, such as waving an independence-themed flag today’, one longtime resident told me.

This is not the end of Hong Kong. It remains a global financial centre, its stock market is still the world’s largest and more capital is set to flow in if Chinese ‘red chip’ companies forced to delist from the New York Stock Exchange decide to relocate here. Multinationals whose business operations focus mainly on China’s massive market would be reluctant to decamp for faraway Singapore. Taipei and Tokyo are making overtures to lure businesses and hedge funds, but neither is as attractive an international English-speaking base as Hong Kong.

But it is the end of Hong Kong as we knew it. I was recently reminded how when I would leave after a lengthy reporting trip in China and cross the border into Hong Kong, I would almost literally feel a breath of fresh air. Unlike the mainland, reporting here was easy. People were willing to talk and express their views strongly. They gave you their names to be quoted. You didn’t have to hide your notebooks or constantly be looking over your shoulder if you pulled out a camera for a photo. Here I did not have to use multiple sim cards and disposable ‘burner phones’ to meet with sources.

That is all now changing. With the new law and the new national security infrastructure, Hong Kong now is becoming like every other mainland city under an authoritarian police state. Citizens scrubbing their social media accounts and scraping pro-democracy stickers off their shops is a sad but telling sign.

The Hong Kong we knew is dead. This is the new normal.

In an age of escalating tension between the United States and China, will the European Union still have room to manoeuvre in pursuit of its own interests? That will be a key question for EU policymakers in the years ahead.

The Sino-American conflict has already become a central issue in the run-up to the US presidential election in November, because President Donald Trump’s administration has clearly decided that bashing China is one way to divert attention from its own failings. But even if Trump loses to his presumptive challenger, Joe Biden, the bilateral confrontation will continue to escalate. Within the US political and foreign-policy establishment, actively looking for ways to curtail, stop, or even reverse China’s geopolitical rise is a bipartisan pursuit.

Yet, even with the most aggressive policies, it is doubtful that the US—or anyone else—could achieve that goal. China’s per capita GDP (adjusted for purchasing power parity) is roughly one-third that of the US or most European countries. But in terms of the overall size of its economy, it is quickly catching up to the US and the EU.

Nobody can know for certain how China’s economic story will unfold in the decades to come; but current trends suggest that it will continue to grow much faster than either the US or the EU. If it can close even half the per capita GDP gap with Taiwan, its economy will have grown (by dint of population) to twice the size of the US or the EU economies.

Despite the Covid-19 pandemic, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank both expect China’s economy to register positive growth this year. Meanwhile, the US and Europe are both experiencing a deep contraction, with no end in sight. The upshot is that the pandemic will further increase China’s relative weight in the global economy.

To be sure, with an ageing population, a massive, loss-making state sector, and growing debt, China will face strong economic headwinds in the coming years, especially if structural reform continues to rank low on Chinese President Xi Jinping’s list of priorities. China’s political system is woefully unsuited for managing a modern society.

Before dying of Covid-19, Li Wenliang, the Wuhan-based physician who was silenced after trying to sound the alarm about the coronavirus outbreak, pointed out that ‘a healthy society should not have just one voice’. By that unimpeachable standard, the Chinese political system is in poor health indeed. It will remain susceptible to all kinds of morbid and unpredictable maladies.

Still, there is no denying that China will be an increasingly important part of the global economy in the years ahead. Its expanding presence will bring new challenges for everyone, but particularly for Europeans. Because Europe can no longer count on the US as a reliable, like-minded partner, it will have to develop its own approach.

The new European strategy toward China should be based on two pillars. On the one hand, engagement on issues of common concern can and must continue. China accounts for nearly 30% of global greenhouse-gas emissions. Because one of Europe’s chief policy objectives is now to pursue a green-energy transition—achieving net-zero emissions by 2050—spurning dialogue with China is not an option.

The same applies to other supranational issues such as trade and public health. Both Europe and China have a strong interest in preserving the global trading system, and that will require cooperation to reform the World Trade Organization. The US’s disengagement from the WTO and the World Health Organization is deeply counterproductive and places an even greater burden on the EU to reform and strengthen these necessary multilateral bodies. The WHO’s latest World Health Assembly showed that the EU can indeed play an important, constructive role in this regard, even as the US continues to marginalise itself.

On the other hand, the EU increasingly sees China as a ‘systemic rival’ whose values and interests will inevitably clash with its own. There is clearly a need for stronger mechanisms to screen Chinese investment in sensitive European sectors and to ensure fair competition between European firms and Chinese state-subsidised corporations. Across a range of issues, European policymakers and diplomats will need to do more to ensure that China lives up to the commitments it has undertaken.

There is little doubt that European public opinion is starting to swing against China and that this will have an impact on policy. With the Chinese regime cracking down on Hong Kong, threatening Taiwan and maintaining its repression in Xinjiang and other regions, it will become much harder for countries like Hungary to block EU actions in defence of human rights and the rule of law in China.

The EU’s task will be to strike a balance between these two pillars. Though Europe will stand together with the US on many issues, it will not abandon its engagement with China on issues of mutual concern. And while Europeans must be realistic about China’s increasing capacity to throw its weight around on the world stage, China’s leaders would do well to remain realistic, too. A violent clampdown in Hong Kong, for example, would force the EU to take a much harder line when devising its new strategic approach.

At times of political crisis, the Chinese government has demonstrated a willingness to deploy disinformation and influence operations to achieve its strategic goals. The regime has mobilised a long-running campaign of political warfare against Taiwan, incorporating the seeding of disinformation on digital platforms.

Our September 2019 report Tweeting through the Great Firewall investigated state-linked disinformation campaigns on Western social media platforms targeting the Hong Kong protests, Chinese dissidents and critics of the Chinese Communist Party.

In our latest report, Retweeting through the Great Firewall: a persistent and undeterred threat actor, we note that this campaign is ongoing, has refined its tactics and focus, and has pivoted to incorporate current protests and civil unrest in the US into pro-CCP narratives.

Working from exclusive access to a Twitter dataset of almost 24,000 accounts and 350,000 tweets it has taken down, we analysed the current evolution of this long-running campaign. The operation targeted audiences in Hong Kong and the Chinese diaspora more broadly, and was likely trying to exploit the internet’s underground marketplace for stolen social media accounts in order to disguise its attempts to drive engagement around narratives aligning with the interests of the party-state.

Twitter has been quite clear in attributing this operation to the People’s Republic of China. Our analysis of the dataset found that the posting patterns of tweets mapped cleanly to working hours in Beijing (despite the fact that Twitter is blocked in mainland China). Posts spiked between 8 am and 5 pm Monday to Friday and dropped off at weekends. Such a regimented posting pattern clearly suggests inauthenticity and coordination.

The Hong Kong protests and the emergence of the global Covid-19 pandemic from China have created a political crisis for the CCP. Faced with the possibility of domestic social and economic upheaval, the regime cannot afford for the pandemic to negatively impact its rising geopolitical influence and so has launched waves of disinformation and influence operations intermingled with its diplomatic messaging.

There is much to suggest that the CCP’s propaganda apparatus has been learning from the strategies and effects of Russian disinformation campaigns. Its tactics include the coordination of diplomatic and state media messaging, the use of Western social media platforms to seed disinformation into international media coverage, the immediate mirroring and rebuttal of Western media coverage by Chinese state media, the co-option of fringe conspiracy media to target networks vulnerable to manipulation, and the use of coordinated inauthentic networks and undeclared political ads to actively manipulate social media audiences. All of these methods have been deployed by the Chinese government to shape the information environment to its advantage.

Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokespeople Lijian Zhao and Hua Chunying have broken with normal diplomatic constraints and, acting in their official capacity, used Twitter to promote disinformation from known fringe conspiracy theory websites globalresearch.ca and thegrayzone.com. Zhao and Hua both tweeted video footage falsely claiming to depict Italians chanting support for China (in response to medical aid).

Chinese diplomats and state media have attempted to use Western voices to counter criticism of China’s handling of the pandemic. State media and multiple diplomatic Twitter accounts, in coordination, repurposed a Facebook post by a Swedish student living in the city of Ningbo that favourably compared China’s response to that of Europe and the US.

Xinhua News Agency distributed an animated video that used similar language to the Swedish student’s post to build on this theme. Xinhua, along with the Global Times, China Global Television Network and China Central Television, ran a series of undeclared political ads critical of US President Donald Trump’s administration on Facebook.

Our report suggests that underpinning this synchronisation of diplomatic and state-media messaging is a layer of covert influence activity, operating at scale. Others are reaching similar conclusions. The US Department of State’s Global Engagement Center has suggested that there are coordinated covert efforts to manipulate global social media in order to amplify PRC diplomats and state media.

ASPI’s internal data analytics platform, the Influence Tracker, has noted unusual patterns in the retweet reach of particular diplomatic Twitter accounts. A study by the Digital Forensic Center identified a rapidly growing network of automated social media accounts praising the PRC’s distribution of medical aid to Serbia, unfavourably contrasting it with the response of the European Union.

A similar study noted analogous bot-driven inauthentic activity attempting to drive pro-China and anti-EU sentiment on Italian social media, including artificial boosting of the Twitter account of the PRC’s Italian embassy. In another investigation, ProPublica analysed a network of more than 10,000 stolen and fake Twitter accounts that were pushing messaging strongly aligned with PRC interests.

There has been some pushback from Twitter on aspects of these assertions. Part of the challenge is in attributing influence operations as state-directed. Making high-confidence judgements about attribution requires assessment of narrative framing, behavioural patterns, technical signals, targeting and intent. There’s a growing influence-for-hire shadow economy to which state actors can outsource to obfuscate involvement.

Further muddying the waters is the scale of pro-China patriotic trolling on social media. Much of this activity may have some degree of authenticity while also amplifying patriotic narratives, harassing regime critics and demonstrating behavioural traits consistent with the inauthentic coordinated networks deployed by state-driven influence operations (like the use of bot networks and coordinated posting patterns). We have previously reported on a range of pro-China, anti-Taiwan trolling campaigns that have echoed CCP interests and spiked during periods of geopolitical tension.

As the Chinese state expands its use of Western platforms, it seeks opportunities to mobilise supporters from within the Chinese diaspora. This mobilisation is a fundamental tenet of the party-state’s view of security and is calculated to exploit the capacity of diaspora communities to extend the party’s influence overseas.

This effort to influence global public opinion is ongoing and is unlikely to relent. The Chinese party-state is invested in information management as a fundamental pillar of its global engagement. The CCP places enormous importance on propaganda domestically and is projecting this approach in its global engagement in an attempt to secure strategic positioning on its own terms.

Chinese diplomats have long had a reputation as well-trained, colourless and cautious professionals who pursue their missions doggedly without attracting much unfavourable attention. But a new crop of younger diplomats are ditching established diplomatic norms in favour of aggressively promoting China’s self-serving Covid-19 narrative. It’s called ‘wolf warrior’ diplomacy—and it’s backfiring.

Shortly before the Covid-19 crisis erupted, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi instructed the country’s diplomatic corps to adopt a more assertive approach to defending China’s interests and reputation abroad. The pandemic—the scale of which could have been far smaller were it not for local Wuhan authorities’ early mistakes—presented a perfect opportunity to translate this directive into action.

And that is precisely what Chinese diplomats have been doing. For example, in mid-March, the foreign ministry’s newly appointed deputy spokesperson, Zhao Lijian, promoted a conspiracy theory alleging that the US military brought the novel coronavirus to Wuhan, the pandemic’s first epicentre.

Similarly, in early April, the Chinese ambassador to France posted a series of anonymous articles on his embassy’s website falsely claiming that the virus’s elderly victims were being left alone to die in the country. Later that month, after Australia joined the United States in calling for an international investigation into the pandemic’s origins, the Chinese envoy in Canberra quickly threatened boycotts and sanctions.

But, unlike the fictional special-operations agents after which they’re named (from a popular Chinese action movie), China’s wolf-warrior diplomats haven’t been rewarded for their recklessly confrontational style. Far from burnishing China’s international image and placating those who blame the country for the pandemic, their actions have undermined China’s credibility and alienated the countries it should be wooing.

Why change tack in the first place? One reason is China’s current combination of historical insecurity, rooted in its so-called century of humiliation, and heady arrogance, fuelled by its immense economic clout and geopolitical influence. So keen are China’s leaders to gain the respect they feel their country deserves that they have become highly sensitive to criticism and quick to threaten economic coercion when countries dare to defy them.

Another reason is the current regime’s emphasis on political loyalty. Under President Xi Jinping’s highly centralised leadership, Chinese diplomats are evaluated not on how well they perform their professional duties, but on how faithfully and vocally they toe the party line. This is exemplified by the appointment last year of Qi Yu, a propaganda apparatchik with no foreign policy experience or credentials, as party secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs—an important post traditionally held by an experienced diplomat.

If aggressively pushing the Chinese Communist Party’s preferred narrative is a matter of professional survival, diplomats will do it, even if they recognise that it’s counterproductive (as many probably do). They certainly won’t try to persuade their political masters to change course. Whereas diplomats risk paying a heavy price for conscientious dissent, they seem to suffer no consequences—from criticisms in official media to demotions or dismissals—for destructive loyalty. When pushing the CCP-approved narrative produces negative results, it is, in party parlance, an issue of tactics, not the ‘political line’. Punishing loyal diplomats for ‘tactical errors’ would make them more reluctant to do the CCP’s dirty work in the future.

By removing any incentive for diplomats to temper their approach and offering a convenient excuse for setbacks, this logic entrenches bad policy. It doesn’t help that China lacks a free press and political opposition to highlight the failures of the wolf-warrior approach. Unlike Western diplomats, those in China don’t have to fear public ridicule or criticism. All that matters is what their bosses say—and their bosses want wolf warriors.

This is a mistake. At a time when China’s reputation is suffering and its relationship with the US is in freefall, the country’s diplomats should be focused on differentiating China’s foreign policy from that of US President Donald Trump.

It is Trump who recklessly promotes conspiracy theories and aggressively responds to any perceived slight with threats and sanctions. It is Trump who foolishly alienates friends and partners, rather than cultivating mutually beneficial relationships. And it is Trump whose belligerent insistence on his country’s superiority has eroded its international reputation and undermined its interests.

China’s leaders should know better.

The United Front … is an important magic weapon for strengthening the party’s ruling position … and an important magic weapon for realising the China Dream of the Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation.

— Chinese President Xi Jinping, Central United Front Work Conference, 2015

The Chinese Communist Party is strengthening its influence by co-opting representatives of ethnic minority groups, religious movements, and business, science and political groups in China and overseas. It claims the right to speak on behalf of those groups and uses them to claim legitimacy. These efforts are carried out by the united front system, which is a network of party and state agencies responsible for influencing groups outside the party, particularly those claiming to represent civil society. It manages and expands the United Front, a coalition of entities working towards the party’s goals. The CCP runs these activities, known as united front work, but its role is often covert or deceptive.

In recent years, groups and individuals associated with the United Front have attracted an unprecedented level of scrutiny for their links to political interference, economic espionage and influence on university campuses. In Australia, businessmen who were members of organisations with close ties to the United Front Work Department (UFWD) have been accused of interfering in Australian politics on China’s behalf. In the US, at least two senior members of united front groups for scientists have been taken to court over alleged technology theft. Confucius Institutes, which are overseen with heavy involvement from the UFWD, have generated controversy for more than a decade for their effects on academic freedom and influence on universities. Numerous Chinese students and scholars associations, which are united front groups for Chinese international students, have been involved in suppressing academic freedom and mobilising students for nationalistic activities in Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States.

The Covid-19 pandemic has also highlighted overseas united front networks. In Australia, Canada, the UK, the US, Argentina, Japan and the Czech Republic, groups mobilised to gather increasingly scarce medical supplies from around the world and send them to China. Those efforts appear linked to directives from the All-China Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese, a united front agency. The party’s Central Committee has described the federation as ‘a bridge and a bond for the party and government to connect with overseas Chinese compatriots’. After the virus spread globally, united front groups began working with the CCP to donate supplies to the rest of the world and promote the party’s narratives about the pandemic.

Regardless of whether those activities harmed efforts to control the virus, they appeared to take governments by surprise and demonstrate the effectiveness of united front work. The CCP’s attempts to interfere in diaspora communities, influence political systems and covertly access valuable and sensitive technology will only grow as tensions between China and countries around the world develop. As governments begin to confront the CCP’s overseas interference and espionage, understanding the united front system will be crucially important.

My ASPI paper, released today, dissects the CCP’s united front system and its role in foreign interference. It describes the broad range of agencies and goals of the united front system and examines how the system is structured, how it operates and what it seeks to achieve. It reveals how dozens of agencies play a role in the united front system’s efforts to transfer technology, promote propaganda, interfere in political systems and even influence executives of multinational companies.

The united front system has nearly always been a core system of the CCP. For most of its history it has been led by a member of the Politburo Standing Committee—the party’s top leadership body. However, General Secretary Xi Jinping has emphasised united front work more than previous leaders, pushing it closer to the position of importance that it occupied in the party’s revolutionary era by elevating its status since 2015.

The scope of united front work is constantly evolving to reflect the CCP’s global ambitions, assessments of internal threats to its security, and conception of Chinese society.

The fact that the United Front is a political model and a way for the party to control political representation—the voices of groups targeted by united front work—means its overseas expansion is an exportation of the CCP’s political system. Overseas united front work taken to its conclusion would give the CCP undue influence over political representation and expression in foreign political systems.

Xi’s reinvigoration of this system underlines the need for stronger responses to CCP influence and technology-transfer operations around the world. However, governments are still struggling to manage it effectively and there is little publicly available analysis of the united front system. This lack of information can cause Western observers to underestimate the significance of the united front system and to reduce its methods into familiar categories. For example, diplomats might see united front work as ‘public diplomacy’ or ‘propaganda’ but fail to appreciate the extent of related covert activities. Security officials may be alert to criminal activity or espionage while underestimating the significance of open activities that facilitate it. Analysts risk overlooking the interrelated facets of CCP influence that combine to make it effective.

Governments should disrupt the CCP’s capacity to use united front figures and groups as vehicles for covert influence and technology transfer. They should begin by developing analytical capacity for understanding foreign interference. On that basis, they should issue declaratory policy statements that frame efforts to counter it. Countermeasures should involve law enforcement, legislative reform, deterrence and capacity building across relevant areas of government. Governments should mitigate the divisive effect united front work can have on diaspora communities through engagement and careful use of language.

Law enforcement, while critically important, shouldn’t be all or even most of the solution. Foreign interference often takes place in a grey area that’s difficult to address through law enforcement actions. Responses to united front work must engage civil society, media and ethnic Chinese communities. They should seek to couple punitive measures for agents of interference with a positive agenda of support for and engagement with communities affected by united front work. Effective efforts to counter foreign interference are essential to protect genuine participation in politics by ethnic Chinese citizens.

As China’s communist leaders prepare to impose a draconian new national security law on supposedly autonomous Hong Kong, officials in Beijing and locally are trying to assure the city’s anxious and angry residents that nothing much will change.

The legislation, approved by the National People’s Congress (NPC) on Thursday, will only apply to a tiny number of ‘terrorists’ and their foreign backers, they say. Local police and courts will still be in charge. The new restrictions, they say, will actually make Hong Kong safer and more stable for overseas investors. And besides, every Western country has its own version of a national security law, so criticism from foreign capitals amounts to hypocrisy and fearmongering.

But Hong Kong’s elected pro-democracy politicians, academics, lawyers, journalists and overseas business groups believe precisely the opposite is true. Everything will change.

After steady erosion, they say—the kidnapping of five Hong Kong booksellers, the expulsion of a Financial Times journalist, China weighing into local court decisions—the law will mark the death of Hong Kong’s autonomy, and of the unlikely dream of ‘one country, two systems’.

The remaining question for many now is how long this freewheeling, capitalist enclave can thrive as a global financial centre and multinational business hub once it becomes just another Chinese city, subject to the controls used to stifle dissent on the mainland.

While Hong Kong’s political future is being dictated from Beijing, its economic future might be decided in Washington.

Hong Kong’s international standing could be further eroded now that the United States poised to implement new sanctions. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has indicated that the White House could revoke its special trade status. President Donald Trump could then impose on Hong Kong punitive tariffs on exports and controls on sensitive technology as he has on China.

One prominent American businessman in Hong Kong predicted that trade, technology and the overall business climate could diminish rapidly. He said the financial sector could be less immediately affected given the strength of the Hong Kong stock exchange, the world’s third largest behind New York and London with over 2,000 listed companies. But that could change, too, if overseas talent becomes harder to attract, if faith in the legal system wanes and if the market manipulation common on the mainland takes hold here.

Hong Kong is already less vital to China than it was 23 years ago at the time of the handover, when its economy accounted for nearly 16% of mainland China’s GDP. Now its barely 3% and ships bypass Hong Kong for mainland ports in Shenzhen and Shanghai.

But the city remains important. Most of China’s foreign direct investment comes through Hong Kong, contracts are signed there because of its reliable legal system, information—vital to capital movements—still flows freely, and Hong Kong’s dollar is a convertible currency pegged to the US dollar. All of that could now be in danger. An immediate rush to the exits is unlikely, but Singapore is likely to be perceived as a safer and more stable long-term bet.

There are too many unknowns to be certain of any outcome. The new law is still being written in Beijing, and will not likely be implemented here for several months. And Pompeo’s statement decertifying Hong Kong only begins a process, leaving Trump with many options depending on how hard he wants to try to punish Beijing.

Jittery residents are waiting to see the fine print of the law that, as expected, won overwhelming support from the NPC, China’s rubber-stamp parliament, with 2,878 votes and only one against, with six abstentions. Now it goes to the more powerful NPC Standing Committee, charged with crafting the precise wording. That will take several weeks.

Will people arrested in Hong Kong for violating the law be tried in local courts, where defendants enjoy more rights, including under international human rights covenants? Or could they be shipped to mainland courts where prosecutors have a 99% conviction rate? Will the law be enforced primarily by the local police, or by agents of China’s feared Public Security Bureau?

And will it be retroactive so that someone can be prosecuted for a statement or a tweet made last year before it was in force? That has many trying to scrub their social media accounts, and downloading virtual private networks, which are illegal in China, though commonly used to bypass censors.

The only template suggesting how the law might be implemented in Hong Kong is the way it’s used in mainland China. That paints a terrifying picture.

Journalists, scholars, lawyers, human rights activists and workers with non-government organisations have all been detained under the mainland’s national security law, usually charged with the catch-all crime of ‘subverting state power’ or ‘inciting to subvert the state’. Trials are typically closed if they involve ‘national security’. Many documents, from mundane economic statistics to the number of people executed for capital crimes, are classified as ‘state secrets’ and reporting them, or possessing them, can lead to prison. Criticism of the one-party state or calls for multiparty democracy amount to crimes of incitement.

Backers of the law say it will only be applied to crimes like treason, subversion, foreign interference and secession, but there are unlikely to be clear legal signposts to what those vague terms mean.

Can Hong Kong academics researching mainland trends run afoul of the law? Can a university hold a symposium on Tibet or Taiwan and invite all sides to participate? Could publishing an interview with the Dalai Lama, or Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen, be deemed a crime? And how broadly will the new law define ‘foreign interference’, which could mean the normal activities of American or Australian NGOs, like human rights or labour groups, providing funding or training for local partners?

In China, attacks on the communist party and its symbols are not tolerated. But in Hong Kong, slogans and banners mocking the party, the Chinese flag and Xi Jinping are common. Will they be outlawed? Already, the local legislature, controlled by pro-Beijing forces, is trying to ram through an unpopular bill to make it a crime to disrespect the Chinese national anthem, ‘March of the Volunteers’.

Local pro-China figures have already hinted that the annual vigil commemorating the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre of hundreds of pro-democracy students could be outlawed.

Little is known about Washington’s next steps.

Despite its divided and divisive politics, there’s a strong and unusually bipartisan consensus in the US to hold China to account for its human rights abuses and for rolling back Hong Kong’s freedoms. Congress has sent to the White House a bill to sanction Chinese officials for their brutal suppression in Xinjiang, where more than a million ethnic Muslim Uyghurs have been sent to concentration camps for ‘re-education’.

Trump has been agitating to punish China for its early lack of transparency over the initial outbreak of the deadly coronavirus in Wuhan, most likely at a wildlife and seafood market not far from a secretive virology laboratory. But Hong Kong’s economic fate could also be tied to the US–China trade war. If Hong Kong loses its special trading status and becomes subject to punitive tariffs, the economic blow to a city reeling from months of protests and the pandemic could be devastating.

The anti-subversion law, and the crackdown it presages, is the result of a collision between Hongkongers’ aspirations for genuine autonomy and the Chinese Communist Party’s imperative to impose control over a restive former British colony that never fully accepted being incorporated into the mainland.

After months of protests, many Hong Kong activists and outside observers were hoping, optimistically, that China’s rulers would not risk tarnishing this city’s global brand as a financial centre, or the approbation from the wider world, with a complete crackdown, and that some compromise might be reached. But it now appears that for China’s leadership, it’s most important to control Hong Kong through force and to crush dissent that might spill over the border.

Before 1997, when Britain handed over the colony, Hong Kong’s fate was decided in London and Beijing, with its people having no say.

History appears to be repeating itself. Hong Kong’s future is now being shaped in Beijing and Washington. And once again, Hongkongers are on the outside looking in.

As the world remains focused on the Covid-19 pandemic, the Chinese Communist Party has set about boiling two frogs. Beijing has turned up the heat on Hong Kong. It’s also stepping up its attempts to isolate and coerce Taiwan.

Both situations present opportunities for Australia and other countries to act to support the freedoms of people in Hong Kong and Taiwan. The reasons to do so are moral and practical: it’s the ethically right thing to do in the face of Beijing’s coercion, and maintaining such freedoms is critical to our own society because it helps create the type of world we want to live in.

The rubber stamp of the National People’s Congress has come down on the hastily produced new national security legislation that Beijing is imposing on the people of Hong Kong. It was done with an unsurprising lack of debate, followed by a mandatory ringing endorsement. But only in Beijing.

When these new national security laws are enacted in Hong Kong, criticism of the Chinese government, acts of public protest, strikes, not singing the Chinese anthem and abusing the Chinese flag will be criminal acts. Protests will be able to be characterised as terrorism and mild criticism of Chinese leader Xi Jinping as sedition, with lengthy jail terms the result.

It also appears that mainland security agencies—like the People’s Armed Police and the ministries of state and public security—will establish formal presences in Hong Kong and enforce the new laws (no doubt using Hong Kong police and authorities as proxies where necessary).

We’re being told that this is all in response to the protests in Hong Kong. What a short memory Beijing is banking on the world having. It can’t be too hard to remember the rolling protests in Hong Kong starting in March last year, some of which involved around 2 million people, or nearly a quarter of the city’s population. These numbers make it impossible to believe that these mass public protests are the work of terrorists or foreign agents. It’s exactly the kind of mass movement for political change that Beijing fears.

It also can’t be too hard to recall that the reason for this mass public movement was a previous effort by Beijing to limit Hongkongers’ freedoms, which the People’s Republic of China guaranteed would remain unchanged for 50 years from 1997 when the UK ceded control of its former colony. That attempt was in March 2019 when Hong Kong chief executive Carrie Lam worked to put an extradition law into effect so that Hongkongers could be tried in mainland China.

That turns out to have been a mild, soft play by the Chinese authorities and internal security apparatus compared with what Beijing has now begun.

Beijing’s intent is clear and aligns with Xi’s mindset that the ruling party is engaged in an endless struggle to maintain its power. That struggle is partly an internal one; an example is Xi’s anti-corruption campaign that has also cemented his supporters within the CCP. But it’s also a struggle against the Chinese people, against ‘separatists and terrorists’ whether in Tibet or Xinjiang (and now Hong Kong), and against other systems of government—particularly democracy, which cuts at the heart of CCP rule.

Back in late 2017, Xi had warned the party that the future held a period of ‘tireless struggle’, although he can’t have known quite how much truth he would wind around this notion in just 30 months. Right from the start, the CCP’s reaction to the pandemic has been flavoured by the struggle for control—in the narrative war with its own people and the wider world and in the enormous economic and geostrategic challenges that China faces as a result.

There has been a strange lack of focus in analysis of Beijing’s pandemic misinformation campaign on the leadership’s drive to stop widespread criticism within China of the party’s response, notably during the early months in Wuhan. Yet Hong Kong needs to be understood in this light.

To the CCP, Hong Kong is all about mainland China. Xi’s actions to repress Hongkongers’ freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, freedom of association and freedom to strike are aimed at preventing the political contagion of freedom from spreading inside mainland China. Freedom of speech could reignite widespread public criticism of the party over the growing problems created by the pandemic.

The Chinese government does not want a vibrant example of political freedom showing its 1.4 billion citizens that there’s an alternative to the authoritarian rule they live under, particularly when that alternative is a part of their own state. So Beijing has decided that now is the right time to engage in that struggle with the people of Hong Kong.

What should the world do? This is a Tiananmen moment for the rest of us. The new laws, and the enforcement and implementation action that Beijing will take as a result, are inflicting tragic human rights abuses on 7.5 million people. It’s possible to prevent at least some of the courageous people of Hong Kong from spending years in Chinese jails for acts (and thoughts) that are guaranteed in the commitments the PRC made before the world in 1997, just as it was possible to save thousands of Chinese citizens from arrest and arbitrary detention in the aftermath of the PLA’s massacre on the streets of Beijing back in 1989.

Doing so involves governments—including Australia, Canada, EU member states, the UK and the US —opening paths to citizenship for Hongkongers fleeing the territory, as Prime Minister Bob Hawke and other leaders did for Chinese citizens fearing a return to the PRC after Tiananmen in 1989. It also involves the nations with Magnitsky-type laws imposing targeted sanctions against individual decision-makers and officials in Beijing and Hong Kong who are putting these repressive, abusive measures into effect.

For Australia, that means fast-tracking the results of the parliamentary inquiry into such a law and then having the courage to act with other international partners by using it. The EU, Canada, Australia, the UK and the US, as well as New Zealand and Japan, have already shown alignment in condemning Beijing’s proposed laws.

Whether it is the right approach to follow potential US action to restrict economic engagement with Hong Kong because the Chinese government is restricting freedom in the territory is another matter. It probably makes more sense to target the sources of the repression—officials in both Beijing and Hong Kong—than it does to cause Hongkongers economic pain along with the physical and psychological pain from Beijing.

And we need to think beyond our noses, and beyond Hong Kong to where Beijing turns next. Having boiled one frog, Beijing is already turning up the heat on another, and we can expect heightened steps to isolate and coerce Taiwan. That’s because Taiwan is the other radioactive demonstration that the CCP’s claim to be the only option as ruler of China is not just self-serving but simply wrong. Taiwan is a physical and political demonstration of this deep untruth, and so must be ‘reunified’ and subjected to party control.

So, while we act on Hong Kong, it’s also an urgent challenge for Australia and other democratic nations to act to reverse the growing isolation of Taiwan and forestall Beijing’s efforts to boil this second frog. What’s possible here are actions like supporting Taiwanese participation and membership in international organisations like the World Health Organization, and a deepening of officials’ contacts and cooperation, as well as enhanced people-to-people and economic partnerships.

We can’t be bystanders in our own world and region, so we must use the tools and paths we have.

China’s decision to crack down on Hong Kong with a new security law has shocked the world. But to those who read the resolution issued last November by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, it comes as no surprise. In that document’s section pertaining to Hong Kong, the CCP signalled its intention to assert full control over the former British colony. Tighter national security laws and the establishment of unspecified new enforcement mechanisms would be just two components of a much larger, more comprehensive strategy.

Now that China is pursuing this strategy in earnest, we should expect it to follow through with the additional measures announced last November. Besides bypassing the Hong Kong legislature with a new national security law, the CCP also intends to change the procedures for appointing the city’s chief executive and principal officials. It will strengthen Hong Kong’s law enforcement capabilities and conduct a campaign to inculcate ‘national consciousness and patriotic spirit’ among Hong Kong’s civil servants and young people. The goal is to integrate the city’s economy much more closely with that of the mainland. As if the much-feared security law wasn’t bad enough, the worst is yet to come.

In any case, implementation of the security law will likely be enough to end the so-called one country, two systems governance model that the city has maintained since returning to Chinese rule in 1997. According to remarks from a deputy chairman of the standing committee of the National People’s Congress, Article 4 of the proposed law will authorise ‘relevant national security agencies of the central government’ to establish permanent operational branches in Hong Kong.

Although we don’t yet know which ‘relevant national security agencies’ this applies to, we can be certain that it will include the Ministry of State Security, the Ministry of Public Security and the People’s Armed Police. Officials from the Cyberspace Administration, which enforces cybersecurity and online censorship, may also be dispatched to Hong Kong.

Worse, the proposed law will give these agencies a sweeping mandate. According to Article 7, each agency will have a duty to ‘prevent, stop and punish any activities that split the country, subvert the power of the state, organize and engage in terrorism, and activities by foreign and external forces that interfere in the affairs of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.’

If the law is strictly enforced, one should anticipate Chinese security agents engaging in surveillance, intimidation and arrests of not only Hong Kong residents, but also foreign nationals deemed to pose a threat to national security. The People’s Armed Police may well be deployed to suppress the large demonstrations and riots that are sure to follow. Although it remains unclear how individuals accused of subversive activities will be prosecuted, there’s a strong possibility that they will be transferred to Chinese courts, where securing convictions for trumped-up charges will be easier than in Hong Kong’s courts, which remain largely independent.

The people of Hong Kong will not submit to China’s police state without resistance. In the near term, the new law’s passage will only escalate tensions in the city, as demonstrated by a recent clash between protesters and Hong Kong police. As Chinese security agents begin their enforcement activities in the coming months, they will likely encounter fierce resistance from local pro-democracy activists. Spiralling violence will precipitate an economic meltdown as capital and talent flee Asia’s global financial hub.

Meanwhile, China hawks in the United States will view this looming catastrophe as a godsend. Last November, Congress passed the US Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act, which requires the US Department of State to certify on an annual basis that Hong Kong ‘continues to warrant treatment under United States law in the same manner as United States laws were applied to Hong Kong before July 1, 1997’. If Chinese security agents start arresting pro-democracy activists and their Western supporters in Hong Kong, it’s impossible to imagine that US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo would allow the department to recertify the city’s status.

Decertification would bring an end to all or most commercial and travel privileges that the US has maintained for Hong Kong since 1997, possibly dealing a fatal blow to the city’s economy. And the US won’t be the only Western country to make China pay a price for its aggressive gambit. For US allies that have been hesitant to take sides in the unfolding Sino-American confrontation, China’s latest move will make their decision much easier. Whatever doubts they may have harboured about plunging the world into another cold war will have been assuaged. China will have left them with no alternative but to join a US-led anti-China coalition.

One can be confident that China’s leaders have considered these calamitous consequences and calculated that imposing the new security law on Hong Kong was worth the risks. The international community must prove them wrong.

Bad assumptions make for bad policies and poor investment decisions. One big one we need to test is the notion that China’s post-pandemic economy is going to rescue the world.

That assumption is flavouring much of the Australian debate on our economic future—and on how we should deal with trade threats from Beijing.

An example is talking about $600 million in ‘lost’ exports to China because of the 80% tariff Beijing has imposed on Australian barley. That $600 million figure is an illusion. It’s based on the amount of barley exported in 2019, which was driven mainly by sales of high-end barley used in brewing beer.

And here’s the problem with that: Chinese consumer demand, especially among the middle class, has plummeted as a result of the pandemic, so prices and sales volumes of many commodities are falling. This is true of Chilean grapes, Egyptian oranges and Peruvian avocados, and it will probably also be true over coming weeks and months of ‘luxury’ commodities bought by China’s middle class—wine is an example that comes to mind.

So, the economics of the pandemic tells us that market projections and sales data from before Covid-19 for a wide range of products—including barley—are not guides to the future. On top of this, businesses must now take into account the realised risk of coercive action by the Chinese government, with barley as Exhibit A.

Back in the heady economic times of mid-2019, McKinsey Global Institute forecast a buoyant consumer market in China ‘on the back of rising incomes’, mainly of the middle class. That’s not the situation now, so resetting our assumptions is critical.

The global financial crisis started in the US and was centred on the international finance system. The Chinese economy was affected by it, but China was not the source of the crisis. And China’s economy and state-driven finance system were in a position to pump-prime their own development and so suck in imports. After a brief, sharp downturn in 2008, China’s economy grew by 8.7% in 2009 and 10.4% in 2010.

Fed by large volumes of our competitively priced iron ore, gas, coal, food and services, China’s economy, along with Australia’s, emerged in comparatively good health.

This time it’s different. China is the place where the pandemic began and, for all the triumphalism from Beijing, the Chinese economy is in no way back in business. The stimulus tools available during the GFC—cheap money from a shadow finance sector and large-scale infrastructure spending—don’t make sense this time because the finance sector is now its own source of risk, and infrastructure oversupply won’t deliver a healthy economy.

More significantly, Chinese consumer confidence is broken. Just like in other countries, government policy is big in China, but consumers’ perceptions of their economic future are bigger. Chinese consumers know that China’s two sources of growth—domestic consumption and global exports—are both undercut by the pandemic.

Along with that, the pressures to alleviate poverty and avoid social unrest are growing. Managing them will drag on growth. The Economist reports that only about a quarter of China’s 800-million-strong workforce is eligible for unemployment insurance, and the number of people left unemployed by the pandemic is perhaps as much as 80 million—nearly 20% of urban workers. Much of the suffering is concentrated in China’s 300 million ‘migrant workers’—Chinese citizens living and working in locations different to their place of registration. Under Beijing’s rules, they are not entitled to government benefits.

Social unrest is an abiding and primary concern for the Chinese Communist Party because it fears the political change it could drive. It’s the reason Beijing spends more on internal security forces than on the Chinese military. It’s also why Beijing continues to repress protests in Hong Kong: political freedom there is dangerous for the CCP on the mainland. These anxieties will be heightened by the suffering of migrant workers.

So, Beijing has to manage unemployment, along with reluctant consumers and an economy dislocated by the pandemic and continuing control measures.

It’s not surprising, then, to find Chairman Xi Jinping doing ‘self-inspection’ tours urging industry and commerce to get the economy up and running. Given the troubled economy, he’s been talking up poverty alleviation and talking down his previous goal of achieving an affluent society. He has also been pushing to reduce ‘dependence on traditional industries like coal and steel’.

China is not the global growth engine it was projected to be in many businesses’ plans.

That raises an urgent question about the extent to which businesses in any sector—not just tourism, tertiary education, beef, barley, wine, and even iron ore and coal—should risk their futures by banking on secure, growing markets in China. The very real business risk from coercive Chinese government behaviour is an additional element that makes this something every company director and shareholder is right to question and test.

The optimal balance for Australian trading sectors will take time to establish. Like with the China market, developing a greater share in other global markets will take time and commitment.

But it’s smart not to fall into the dangerous and lazy trap of thinking that the economic path out of Covid-19 is the same as it was for the GFC and leads through Beijing.

None of this means ‘shutting the gate in respect of China’, as some of the more outlandish characterisations of the debate have claimed. There’s still a foundation of mutual benefit in the economic relationship. And Beijing’s concern around the political implications of its domestic economic weakness may moderate its willingness to inflict further self-harm through further coercion of Australian and other businesses.

We need to be clear-headed when making fundamental economic decisions and bring to those decisions an understanding of the actual economic pressures China faces, as well as of the Chinese government’s role and nature. The good news is this seems to be the path that Prime Minister Scott Morrison is on, with the support of the federal Labor Party. The Australian public understands this, although some business leaders and state politicians have some catching up to do.

Beyond China, it’s also smart to consider what new value our customers and partners will place on trade with Australian businesses because of the safety and reliability we’ve shown during the pandemic. For example, there’s an important opportunity for Australian farmers provided by rising global food insecurity. Partnerships between government and industry can help grow these other markets as we all recover.

Along with assessments of China, the potential to grow new and existing markets is another assumption to test as we work towards building a place for Australia in the world after Covid-19.