Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Last month, US President Donald Trump signed into law a bill allowing him to impose sanctions on Chinese officials involved in the mass incarceration of more than one million Uyghurs and members of other largely Muslim minorities in the western Chinese region of Xinjiang. The bipartisan Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act of 2020 (UHRPA) condemned the abuses and called on the Chinese authorities to close their ‘vocational education’ centres in the region immediately, ensure respect for human rights, and allow people living in China to re-establish contact with family, friends and associates outside the country.

In theory, Trump could show genuine global leadership by implementing the act vigorously. Researchers in many countries have reported that, in addition to detention, Uyghurs are being subjected to torture, forced labour and sterilisation. And two Uyghur groups have accused the Chinese authorities of physical and cultural genocide in a complaint filed with the International Criminal Court.

Anne Applebaum has compared Western indifference to what is happening in Xinjiang today with the wilful determination of European governments and the Vatican to ignore the famine Joseph Stalin engineered in Ukraine in 1932–33, and the Nazi concentration camps a decade later. One might add more recent examples to the list. Viewed against this background, the United States’ willingness to condemn China’s behaviour and impose costs for it, even if only with individual sanctions, is a step in the right direction.

Moreover, this step might well gain the attention of Muslims in countries like Pakistan, Indonesia and Turkey. The Pakistani and Indonesian governments are willing to play by Chinese rules in order to secure investment; Pakistan signed a letter last year defending China’s treatment of Uyghurs, while the Indonesian government says that it ‘will not meddle in the internal affairs of China’. Turkey initially offered Uyghurs asylum in the 1950s when Chinese communists took over Xinjiang. Today, Turkish police are reportedly arresting Uyghur activists and sending them without explanation to deportation centres, sometimes for months.

In this context, a broad US-led effort to hold the Chinese government even partly to international account for its treatment of Uyghurs—particularly at a time when America is having to reckon with its own current and past racist crimes—could mark an important turning point. At the very least, it would remind China that the world is watching.

Sadly, Trump’s actions will likely convince Muslims only of the depths of his hypocrisy. Trump signed the UHRPA on the same day that allegations contained in his former national security adviser John Bolton’s new book were flooding the airwaves. According to Bolton, Trump was not merely indifferent towards Uyghurs’ human rights, but actively encouraged Chinese President Xi Jinping to build concentration camps to hold them.

Then there are Trump’s own Muslim travel bans. The initial ban, issued in January 2017, barred all refugees and immigrants from several predominantly Muslim countries from entering the US; the measure was struck down by the courts and then revised several times until it passed constitutional muster. Since then, numerous stories have emerged demonstrating the devastating and potentially life-threatening impact of these restrictions on refugees, Muslims and non-Muslims living in the designated countries.

One of those affected is Afkab Hussein, a former Somali refugee now living in Columbus, Ohio. Afkab has been waiting since 2015 for his wife and young children to join him in the US, but Trump’s bans have prevented them from doing so. Trump’s support for a law that calls on the Chinese authorities to permit re-establishment of contact between people in China and outside the country therefore rings hollow.

The UHRPA also accuses the Chinese government of ‘using wide-scale, internationally-linked threats of terrorism as a pretext to justify pervasive restrictions on and serious human rights violations’ against Uyghurs and others in Xinjiang. But Trump’s executive orders seeking to bar Muslims from entering the US included similar clauses.

His first executive order cited the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks on the US as a justification for banning refugees and immigrants from Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen, despite the absence of evidence that citizens of any of these countries, much less refugees, carried out the attacks. Subsequent iterations of the ban continued to cite terrorism as a rationale. In practice, however, the Trump administration has merely blocked family members from joining loved ones in the US, and reduced admissions of vulnerable refugees to historically low levels.

The tension between Trump’s belated embrace of Uyghur rights and his all-too-evident dislike of Muslims (unless they are Saudi princes) raises the deeper question of who the ultimate audience is for America’s—or any country’s—foreign policy. Ordinary Muslims can have no doubt about how Trump feels about them, no matter what he might say to their governments. They only have to follow his Twitter feed or watch his press conferences.

Trump is the first US president to disdain normal processes for crafting and vetting official statements, preferring instead to engage directly with US voters and citizens of other countries via social media. But although he has mobilised a large constituency, he has also succeeded in alienating large segments of the public in America and elsewhere. His denigration of entire populations—such as calling Mexicans rapists or Muslims terrorists—resonate louder and longer than any official statements issued by the White House or the US State Department.

It remains to be seen whether those impressions will outlast Trump’s presidency. The US House of Representatives just passed the ‘No Ban Act’, which would repeal the Muslim travel ban and prevent the use of religious discrimination to bar immigrants. And if a new US administration succeeds Trump following November’s presidential election, it will have to address other countries’ governments and citizens with one voice—and without the glaring hypocrisy to which they have grown accustomed.

As the world struggles to cope with the Covid-19 pandemic, which first emerged in China, Chinese President Xi Jinping is pursuing his quest for regional dominance more aggressively than ever. From the Himalayas to Hong Kong and Tibet to the South and East China Seas, Xi seems to be picking up where Mao Zedong left off, with little fear of international retribution.

The parallels between Xi and the despots of the past are obvious. He has overseen a brutal crackdown on dissent, engineered the effective demise of the ‘one country, two systems’ arrangement with Hong Kong, filled concentration camps and detention centres with Uyghurs and other Muslims in Xinjiang and laid the groundwork to remain president for life.

According to US National Security Adviser Robert O’Brien, ‘Xi sees himself as Josef Stalin’s successor’. Many others have compared Xi to Adolf Hitler, even coining the nickname ‘Xitler’. But it is Mao—the founding father of the people’s republic and the 20th century’s most prolific butcher—to whom Xi bears the closest resemblance.

For starters, Xi has cultivated a Mao-style personality cult. In 2017, the Chinese Communist Party enshrined in its constitution a new political doctrine: ‘Xi Jinping thought on socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era’. The ideology is inspired by Lenin, Stalin and Mao, but its inclusion in the CCP’s constitution makes Xi the third Chinese leader—after Mao and the architect of China’s modernisation, Deng Xiaoping—to be mentioned in the document. In December, the CCP also conferred upon Xi a new title: renmin lingxiu, or ‘people’s leader’, a label associated with Mao.

Now, Xi is working to complete Mao’s expansionist vision. Mao’s China annexed Xinjiang and Tibet, more than doubling the country’s territory and making it the world’s fourth largest by area. Its annexation of resource-rich Tibet, in particular, represented one of the most far-reaching geopolitical developments in post-World War II history, not least because it gave China common borders with India, Nepal, Bhutan and northernmost Myanmar.

In fact, Mao considered Tibet to be China’s right-hand palm, with five fingers—Nepal, Bhutan and the three Indian territories of Ladakh, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh—that China was also meant to ‘liberate’. Mao’s 1962 war against India helped China gain more territory in Ladakh, after it earlier grabbed a Switzerland-sized chunk, the Aksai Chin region.

In April and May, Xi had the People’s Liberation Army carry out a series of well-coordinated incursions into Ladakh, with the intruding forces setting up heavily fortified encampments. He then deployed tens of thousands of troops along the disputed Line of Actual Control with Ladakh, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh.

This ‘incredibly aggressive action’, as US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo called it, led to bloody clashes in Ladakh on 15 June, leaving 20 Indian soldiers and an unknown number of Chinese troops dead. (US intelligence agencies believe China suffered more casualties than India, but whereas India has honoured its fallen as martyrs, China has refused to divulge its losses.) Despite continuing bilateral efforts to disengage rival forces, the spectre of further clashes or a war still looms.

The CCP has not forgotten about the other two fingers, Bhutan and Nepal. Just as China and India began withdrawing troops from the site of the 15 June clashes, Beijing opened another front in its bid for territorial expansion, asserting a new claim in Bhutan.

In 2017, China occupied the Doklam Plateau—at the intersection of Tibet, Sikkim and Bhutan, and claimed by the latter—following a 73-day military standoff with India, the de facto guarantor of Bhutanese security. Now, China is laying claim to another 11% of the tiny kingdom’s territory, in an area that can be accessed only through Arunachal Pradesh (which Chinese maps already show as part of China). This move advances Xi’s efforts against two of the five fingers simultaneously.

The fifth ‘finger’, Nepal, has been drifting away from India and towards China since it came under communist rule two and a half years ago. China aided the Nepalese communists’ victory, including by unifying rival factions and funding their election campaign. Since then, China has openly meddled in the country’s fractious politics in order to keep the ruling party intact, with its ambassador acting as if she were Nepal’s matriarch.

But being in China’s strategic orbit has done nothing to protect Nepal from the CCP’s territorial predation. Last month, a leaked Nepalese agricultural department report warned that China’s massive road projects have expanded China’s boundary into northern territories of Nepal and changed the course of rivers.

Of course, altering Asia’s water map is nothing new for China. Tibet is the starting point of Asia’s 10 major river systems. This has facilitated China’s rise as a hydro-hegemon with no modern historical parallel. Today, Chinese-built mega-dams near the borders of the Tibetan Plateau give the country leverage over downstream countries.

As the hand metaphor indicates, Tibet is the key to China’s territorial claims in the Himalayan region—and not only because of geography. China cannot claim the five fingers on the basis of any Han ethnic connection. Instead, it points to alleged Tibetan ecclesial or tutelary links, even though Tibet was part of China only when China itself had been conquered by outsiders like the Mongols and the Manchus. China’s current claims are nothing more than a power (and resource) grab.

In other words, the five-fingers strategy, coupled with Chinese expansionism elsewhere, is all about upholding the world’s longest-running autocracy. As long as the CCP—and especially the revisionist Xi—holds a monopoly on power, none of China’s neighbours will be safe.

Hopes and fears about the South Pacific drive Australia’s policy ‘step-up’—along with the great needs of Papua New Guinea and the islands.

The hopes and needs get talked up while the fears quietly shape policy.

See that mix in the defence strategic update announcement that the Jindalee operational radar network (JORN), an over-the-horizon radar, will be extended ‘to provide wide area surveillance of Australia’s eastern approaches’.

‘Eastern approaches’ is a polite way of saying ‘Melanesia’.

Australia wants a constant view of every ship and plane operating in our South Pacific arc. What JORN does today for Australia’s northern and western approaches is to be extended to the east.

The Jindalee network is a wonder of Oz science and engineering, based on research started in the 1950s that became a core project in 1970. If it were suddenly invented tomorrow we’d be agog at the achievement: the perfect all-seeing answer for a nation with its own continent ‘girt by sea’.

Bouncing signals off the earth’s ionosphere, JORN does wide-area surveillance. A high-frequency radio signal is beamed skywards from a transmitter and refracted down from the ionosphere to illuminate a target. The echo from the target travels back to a separate receiver site and data is ‘processed into real-time tracking information’.

In Jindalee’s development phase, milestone moments were when the first ship was detected in January 1983, and an aircraft was automatically tracked in February 1984.

The air force says Jindalee’s range is from 1,000 to 3,000 kilometres, depending on atmospheric conditions.

With favourable conditions in the ionosphere (when the signal keeps bouncing) Jindalee can see a helluva long way. Several decades back, what’s known in my trade as a senior government source told me that Jindalee could sometimes track the Russian Backfire bombers taking off from the airbase at Vietnam’s Cam Ranh Bay. Take that as a boast neither confirmed nor denied, merely underlining that Jindalee is amazing kit.

As Defence Science and Technology puts it: ‘The JORN network is Australia’s first comprehensive land and air early warning system. It not only provides a 24-hour military surveillance of the northern and western approaches to Australia, but also serves a civilian purpose in assisting in detecting illegal entry, smuggling and unlicensed fishing.’

The air force says JORN can detect air targets the size of a Hawk-127 training fighter or larger, and objects on the surface of the water the same size as an Armidale-class patrol boat (56.8 metres long) or larger. Detecting wooden fishing boats is harder, or, in the RAAF’s words, ‘highly unlikely’.

The strategic update announced that the JORN site at Longreach in central Queensland will be expanded to look east as well as north. At the moment, the Longreach transmission station can cover most of Papua New Guinea and further north to the Bismarck Sea.

A new eastern array will be able to sweep around from PNG to cover Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and New Caledonia, probably reaching out as far as Fiji.

The timeline for the build is vague. The update allocates $700 million to $1 billion to ‘Operational Radar Network Expansion’, in the period to 2030. Much of that will be for Jindalee to look towards Melanesia.

Australia wants to turn a constant eye on a South Pacific that is, in a phrase du jour, more crowded and contested. See an islands element in the strategic update’s discussion of an era of state fragility, marked by coercion, competition, grey-zone activities and increased potential for conflict.

A driver for the Jindalee decision is found in an understated sentence in the Pacific chapter of Malcolm Turnbull’s memoir: ‘In recent years, China has been reported as taking an interest in establishing a naval base in variously PNG, Vanuatu and Solomon Islands.’

Those ‘reports’ express what Canberra thinks is a grave new fact: our strategic interests in the South Pacific are directly challenged by China. That galvanising fact casts a deeply different light on Australia’s desire to be the preferred security partner of the islands. It’s a thought about China at the heart of the third paragraph of chapter 1 of the strategic update:

Since 2016, major powers have become more assertive in advancing their strategic preferences and seeking to exert influence, including China’s active pursuit of greater influence in the Indo-Pacific. Australia is concerned by the potential for actions, such as the establishment of military bases, which could undermine stability in the Indo-Pacific and our immediate region.

Link the concerned thoughts in that sentence about ‘establishment of military bases’ and ‘our immediate region’ to express this judgement: Australia thinks China wants a base in Melanesia.

If that fear becomes a reality, Australia will have a constant eye for every ship and plane.

The polarisation of politics in the United States, where belief in the danger of coronavirus has become the latest partisan divide, has been fuelled by the impact of Chinese competition on traditional manufacturing districts.

The economic basis of US political polarisation has been demonstrated in a new paper from leading economist David Autor which shows how the middle political ground has disappeared in the districts most affected by Chinese competition. Non-Hispanic whites have veered to the right of the Republicans, while African Americans and Hispanics have swung to the left of the Democrats.

Autor’s latest paper, written with a group of co-authors, builds on his pioneering work showing that the economic principle that trade benefits everyone doesn’t hold true when individual districts are examined.

Economic theory going back to Adam Smith and David Ricardo in the 18th century contends that the jobs lost to import competition will be made up by new jobs generated elsewhere. However, Autor found that the inroads made by Chinese exporters into the US market following China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2000 were accompanied by rising unemployment, lower labour force participation and lower wages in US manufacturing districts.

His latest study shows that the economic shock has had major political effects. Although the gains in support to the right of the Republicans have broadly matched the gains to the left of the Democrats, the Republican gains have come from swing seats, whereas the Democrat gains have come in districts they already held.

The overall result has been an increase in the number of conservative Republican representatives in Congress. The study emphasises that ‘trade shocks appear to catalyze support for more extreme actors in both parties, at the expense of moderates, indicat[ing] that we are not simply capturing a general rightward shift in US politics’.

However, the electoral impact has been heavily in Republicans’ favour. Between 2002 and 2016, the probability of moderate Democrats getting elected more than halved, while the probability of a conservative Republican winning office rose by 85%.

There was also a statistically significant impact on US presidential elections, with trade-exposed districts more likely to vote Republican. The study found that voter turnout and political donations were both higher in the most trade-exposed districts, suggesting this phenomenon increases the intensity of election campaigns.

Although the Republicans have traditionally been the ‘free trade’ party, Republican representatives in trade-exposed areas tend to be protectionist. The protectionist sentiment was captured by Donald Trump’s ‘America first’ slogan in his successful 2016 election campaign.

While Chinese competition has been far from the only cause of structural change in US industry, the study argues that the impact of technology has been felt in both wealthy cities populated by white-collar professionals and factory towns populated by blue-collar workers, whereas only the latter group has been displaced by import competition. It’s in the factory towns that political polarisation has been most acute.

The primary indicator of the polarisation in US politics is partisanship: the extent to which people like their own party and dislike the opponent. A study by the Pew Research Center showed that US voters felt more warmly towards their own party in 2019 than they did at the time of the 2016 election and had become much more hostile towards the opposition.

The survey ranks how warmly people feel about a party on a scale of 1 to 100, and found that among Democrat voters, the score for their own party rose from 67 to 82 between 2016 and 2019. There was a smaller rise from 77 to 84 among Republicans.

The shift in views about the opposition, measured on a similar scale tracking ‘coldness’, is more extreme: Democrat views of Republicans went from 56 to 79, and Republican views of Democrats went from 58 to 83.

Around half the voters for both Republicans and Democrats say voters for the other side are more immoral than other Americans, and large majorities say the other side is more close-minded. The division is evident everywhere: recent surveys show Republicans think the worst of the coronavirus pandemic is now history, whereas Democrats believe it still lies ahead.

None of these trends is evident in Australia. A new study of political polarisation across nine countries found that the US had become much more polarised than other nations, though there was also an increase in polarisation in Canada, New Zealand and Switzerland. By contrast, the level of polarisation fell in Australia, Germany, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

The Australian result may surprise those who recall the bitterness of political division during the governments of Kevin Rudd, Julia Gillard and Tony Abbott. It draws on the findings of the Australian election study conducted by Australian National University researchers showing that voters have become less firmly committed to their own party and less hostile towards the opponent.

The big political trend in Australia over the past 20 years has been the growing share of the vote captured by minor parties, amid disaffection with the two major parties.

The manufacturing sector in Australia has not suffered the squeeze from Chinese competition to the same extent as in the US. The big hit to Australian manufacturing occurred in the 1980s and 1990s in response to the lowering of tariffs and the floating of the Australian dollar.

By the 2000s, much of the surviving Australian manufacturing industry was in subsectors where there was a comparative advantage, such as food or resource industry supplies, or where there was natural protection, such as building materials which are too bulky or heavy to ship.

Although areas of Australian manufacturing did suffer during the 2000s as the resources boom drove the Australian dollar to its 2011 peak of US$1.10, there was a clearer positive effect on the Australian economy from engagement with China, with the resources boom contributing to gains in household living standards across the income distribution.

While the latest Lowy Institute poll shows that Australians are increasingly disenchanted with China, this reflects what they learn from the media and political leadership, rather than being a visceral reaction to their own lived experience, as has been the case in the US manufacturing heartland.

The Hong Kong national security law establishes two new agencies: an all-powerful and unaccountable secret police force targeting Hong Kong and a secret intelligence agency that’s explicitly beyond the law and which Hong Kong officials must unquestioningly obey.

The law makes any criticism of the government of Hong Kong, the People’s Republic of China and the Chinese Communist Party a criminal offence, and only the National People’s Congress (not any Hong Kong court) is empowered to interpret the law’s meaning. It is a completely unaccountable tool for arbitrary arrests at the whims of the CCP. Whether it is used that way will be a matter for the CCP, not for Hong Kong’s government or courts.

Unaccountable, unquestionable, all-powerful secret intelligence and police officers with their own prosecutors and courts and a mandate to investigate and make arrests for political crimes gives these agencies all the powers of the worst of the world’s secret police forces.

First, the national security law establishes the Committee for Safeguarding National Security in Hong Kong. The committee is constituted as a secret, unquestionable authority with its own police force, its own prosecutors and its own judges, all under the control of the central government in mainland China.

The committee is established explicitly under the direct supervision of the central government, and because it includes senior cabinet members and government officials, it tightens Beijing’s already considerable control over those individuals. The supervised members of the committee include Hong Kong’s chief executive and the cabinet secretaries for administration, finance, justice and security, along with senior bureaucrats including the director of the chief executive’s office, the police commissioner, the customs commissioner and immigration director. They are to be ‘advised’ on their duties by a Beijing-appointed national security adviser, a role that appears to now be the most powerful position in Hong Kong.

The committee is to have a permanent secretariat headed by a central government appointee. It is forbidden for anyone to interfere with or disclose any information about what the committee does. Its decisions are not subject to any review.

The committee will have its own private police force housed within the Hong Kong Police Force but run by a central government appointee and staffed in part by personnel from the mainland. The national security police are required to carry out tasks assigned to them by the committee, acting on instructions from its national security adviser. Cases will be prosecuted by a dedicated division housed inside the justice department but run by a central government appointee. The committee will hand-pick judges to hear its cases.

At the discretion of the justice secretary, trials can be held in secret, with only the final judgement required to be held in open court. Hand-picked judges are allowed to act in place of a jury. Any appeal against the justice secretary’s decision to hold a trial in secret or without a jury will be determined at the sole discretion of Hong Kong’s chief executive.

The committee has normal police powers as well as powers to prevent anyone from leaving Hong Kong, to require the removal of any online information, to monitor and interrogate people (explicitly including foreign political or government officials), and to intercept communications.

The national security law also establishes a secret intelligence agency, the Office for Safeguarding National Security in Hong Kong, to be staffed entirely by mainland officers who must be obeyed by the Hong Kong government but who are not themselves subject to Hong Kong law (or any law anywhere, as law professor Don Clark points out). The office extends the jurisdiction of mainland national security laws, courts and criminal procedures to everyone, everywhere.

The office’s first task is to embed itself in the Hong Kong liaison office and foreign affairs bureau, the People’s Liberation Army’s Hong Kong garrison, and all other national security institutions in Hong Kong. It is expected to ensure that foreign non-government organisations and media are compliant.

The national security office is a central government agency and is expected to claim jurisdiction over matters that involve international sensitivities. When the office claims jurisdiction over a matter, all investigations, prosecutions and judicial processes will occur within mainland institutions according to mainland criminal procedures.

The office and its staff are explicitly beyond the jurisdiction of Hong Kong. An agency ID places a person beyond the law entirely while also compelling the obedience of any Hong Kong public official.

The national security law criminalises four types of acts: separatism, subversion, terrorism and collusion. In each case, encouraging or supporting a perpetrator (whether in kind or financially, directly or indirectly) is explicitly criminal.

Separatism offences include planning non-violent efforts to separate Hong Kong from the PRC. Providing any assistance to such an act is also an offence, with sentences of up to five years for minor matters, even if assistance is given without knowledge that it would be used for a separatist act.

Subversion offences include encouraging, planning, supporting or conducting any act that forcefully interferes with the Hong Kong government or central government or any facilities they use. Organising a protest outside the Legislative Council and blocking a train station, bus route or road are in this category.

Terrorist offences are limited to coercive acts that cause or are intended to cause grave social harm, though ‘grave social harm’ is to be interpreted by the standing committee of the National People’s Congress (as are all other articles in the law). Besides the usual descriptions of terrorism, sabotaging transport facilities is explicitly listed, presumably to include the damage done to train stations and roads by protestors. International media covering protests or interviewing protest advocates could be considered to have provided support to or incited terrorism.

Collusion offences include asking for or receiving any kind of help or instruction from a foreigner to disrupt any government policy. This could include any member of the Hong Kong or Taiwan diaspora communicating in support of protests. It includes provoking hatred towards the central government or Hong Kong government, which may include all the activities of opposition political parties or unsympathetic media organisations. It could potentially include any criticism of the Hong Kong government, the central government or the CCP anywhere in the world, or the sharing of an article that includes criticism of the Hong Kong government, central government or CCP.

The offences outlined under the national security law include serious crimes, but they also include political ones. Only the CCP is empowered to determine what constitutes a crime and such decisions are made in secret. There is no process of appeal and no mechanisms for accountability or transparency except to the CCP itself, and all decisions are final. The enforcers of these laws are themselves explicitly above the law and must be obeyed.

Just how dangerous the national security office and the national security police ultimately become to the people of Hong Kong depends on how they use their new powers. What they do have, though, is all the unrestrained authority and immunities of history’s most sinister secret police—if they choose to use them.

The United Nations Human Rights Council recently voted on a resolution supporting China’s draconian national security law that has effectively crushed free speech and freedom of assembly in Hong Kong.

The resolution was carried with the support of 53 nations including Cuba, Iran, Venezuela and, of course, China. Many of the supportive nations have questionable human rights records.

The ‘yes’ votes included a mix of nations that always align with China and others, many from Africa, that were added to the list because they’re locked into infrastructure projects under Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative.

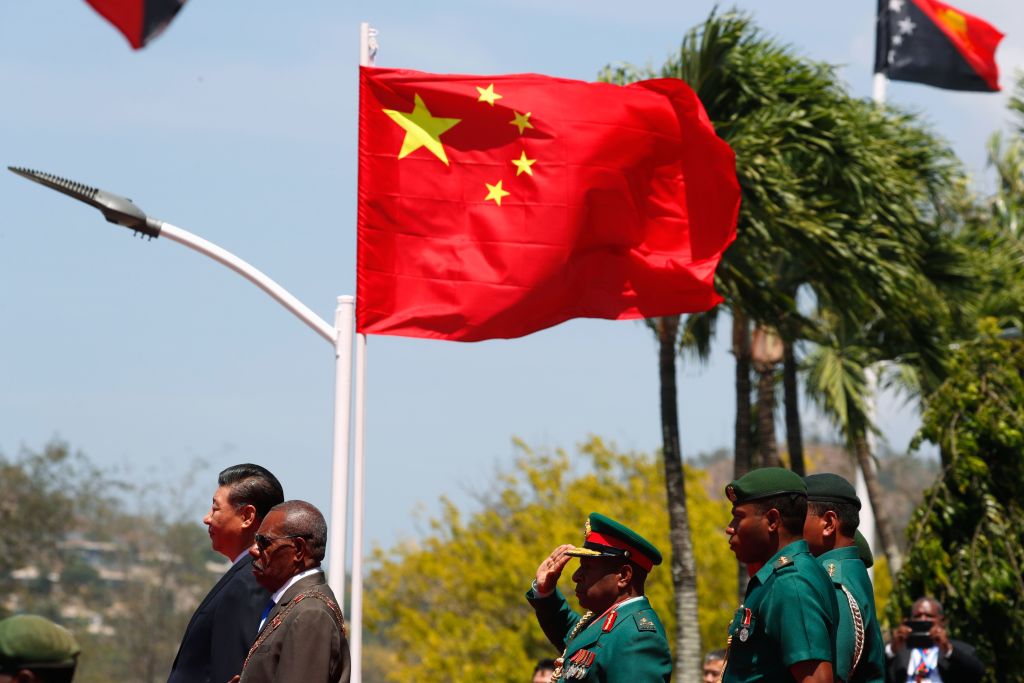

Papua New Guinea voted ‘yes’. Sadly, that has not been reported in PNG’s daily media, or even on social media.

By voting to support the crushing of free speech and freedom of assembly, among other basic rights, PNG voted against the spirit of its own constitution, adopted at independence in 1975, which guarantees those rights for its citizens, along with a free press.

To its enduring credit, PNG’s Supreme Court has vigorously protected these constitutional freedoms against legislation and against regulations seeking to erode them or even put limits on them.

PNG’s vote in the Human Rights Council is a sad reflection of the state of foreign policy in our closest neighbour. Instead of pursuing an independent policy, also provided for in the constitution, PNG is increasingly aligning itself with the People’s Republic of China when it counts.

This has not been debated seriously in the national parliament or, I suspect, even by the National Executive Council, PNG’s cabinet.

There can be only two reasons why PNG voted as it did, and as it increasingly does in regional and international forums. Both present serious foreign policy challenges, and regional security and stability challenges, for Australia.

First, PNG acted in similar fashion to the African nations lined up behind China—the PNG government signed up to the BRI in 2018 and that program is gradually expanding across the South Pacific.

There can be no doubt that funding, principally via heavily conditional loans, under the BRI for developing nations—and jurisdictions in developed countries, such as the state of Victoria in Australia—depends on these countries and jurisdictions supporting the PRC line in bodies where it exerts considerable influence, such as the Human Rights Council and the World Health Organization.

PNG is now locked into that, though neither the parliament nor the people were told this would be the case when, with much fanfare, PNG signed up to the BRI.

The second reason is less certain, but more profoundly troubling if it is true.

PNG has yet to agree to an emergency support package led by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, which is probably worth at least $3 billion. Negotiations are believed to be continuing but, frankly, PNG is running out of time.

The PNG economy is deteriorating rapidly, a problem that’s hardly helped by the continued closure of the Porgera Gold Mine which the government is seeking to effectively nationalise.

The government is running out of cash, with the fortnightly payroll for the public service and parliamentarians being delayed regularly.

The problem the government clearly has with the IMF–World Bank package is the conditions that will come with it. Past experience indicates that those conditions will include a substantial currency devaluation, asset sales, and a substantial reduction in the size of the public service.

With national elections now less than two years away, such a package is hard for the government to embrace.

The real concern is that, out of sheer desperation, the government might do what it was clearly contemplating almost a year ago and accept a substantial rescue package funded by the PRC.

Australia intervened just in time and provided a $400 million soft loan (which is unlikely ever to be repaid) that effectively replaced emergency assistance from China, and put on hold a much larger package.

In desperate times—and these are the most desperate times in PNG’s history—governments surrender good fiscal policy and even national integrity and security. We can only hope that’s not what PNG will do in the coming months.

The question which now arises is how Australia should respond to this troubling reality.

The answer must not be to give PNG more cash handouts as we did a few weeks ago when we agreed to convert $20 million from the aid program to cash.

We have to encourage PNG to accept the IMF–World Bank package, to which we will no doubt contribute, without delay.

We must also encourage PNG to address investment policy issues that are impeding the development of major resource projects, especially those in which there is Australian equity, such as the Wafi-Golpu mine project and the Papua LNG project.

As I have written before, Australia must urgently and comprehensively review its generous aid program so that it reduces waste and bureaucracy and focuses on the real needs of the people of PNG.

Hundreds of programs that are poorly implemented and managed undermine our credibility in our closest neighbour. They must be urgently refocused on helping PNG reverse the real decline in the basic living standards of its people—people who value the friendship with Australia and are rightly suspicious of the growing lock China has on key areas, now clearly including foreign policy.

The Australian government’s ‘Pacific step-up’ program alone cannot do that if it means continuing the same aid programs and simply adding more dollars to them. Our relationship with our closest neighbour is vital for our national security and the stability of our region.

It needs urgent and robust repairing and refocusing.

The 2020 defence strategic update is analysis framed by numbers (and dollars), a melding of meanings and means and mental maps.

To follow the strategic accounting, see what the update counts. Find the strategy in the numbers.

As usual in Oz defence thinking, the United States is the country that Australia mentions the most—it’s referred to in the update 17 times, plus twice in the formulation ‘US-led coalition’.

Of the seven defence white papers Australia released between 1976 and 2016, the US was top of the pops in six. The only time it wasn’t the most discussed nation was in the 1976 document (just after the Vietnam defeat), when Australia talked more about Indonesia and the Soviet Union.

In the update (as in the 2009, 2013 and 2016 white papers), China supplants Indonesia to take second spot in the most-mentions hierarchy.

China gets nine update mentions, but in five of those it’s in the joined phrase ‘the United States and China’. And two of the China sightings are when the document refers to the South China Sea, talking about ‘militarisation’ and ‘coercive para-military activities’.

The update refers to Japan five times. Indonesia is mentioned once, but with four references to ASEAN that counts as five Indonesia sightings. India is mentioned three times; add four references to the ‘north-eastern Indian Ocean’ for seven India sightings.

If the 2016 white paper marked ‘the return of geography to defence planning’, as Paul Dibb remarked back then, the 2020 update is geography triumphant.

Consistent with Oz usage since the 2013 white paper, Australia’s region is the Indo-Pacific (25 mentions) but—back to the future—the area of primary strategic interests is Southeast Asia and the Southwest Pacific. Dibb calls this ‘decisive refocus’ both a ‘radical shift’ and a return home to defence of Australia. Another wise owl, Geoffrey Barker, sees a new defence paradigm.

Turn to themes and memes. Through the seven defence white papers Australia’s defence thinkers have always worried about self-reliance and order. The r’s reign: rules and self-reliance and region.

In the 2016 white paper, ‘rules’ appeared 64 times—48 of those in the formulation ‘rules-based global order’. The rules repetition was a fearful chant about what’s fraying.

Come the 2020 update, the rules-based order gets three mentions, along with a further two references to rules and norms. The context is fretful discussion about how rules are strained, undermined by disruptions; stability is challenged; and pressures on governance in the global commons are causing friction.

Rules are trumped by threats in the update, with a total of 12 mentions of coercion or coercive activities, to achieve strategic or economic goals without provoking conflict.

As coercion is code for China, you could redo the count to argue that there are more update sightings of China than of the US. That’d be a notable shift in the way Australia orders its strategic thinking. Not so long ago, the rules-based order was also code for US leadership; unfortunately that bit of code has turned to gibberish under President Donald Trump.

China fires up lots of ‘c’ words in the US and Oz vocabulary. The US’s new ‘strategic approach’ to China is to compete, compel and challenge.The update’s discussion of the strategic environment uses ‘competition’ or ‘competitive’ a dozen times, with formulations such as ‘greater strategic competition’ and ‘major power competition’ between the US and China.

Facing coercion in ‘a more competitive and contested region’, Australia’s new defence meme is shape-shifting.

The heading ‘Shape Australia’s strategic environment’ is up first in the defence policy chapter and that thought becomes a chant, with 12 references to Australia’s intent to shape our strategic environment.

Doing the count (finding the topography in the typography) sifts for shifts in language and changes that are such big breaks they mark inflection points.

Along with shaping, the other new bit of vocab put in lights is another way of talking about coercion—‘grey zone’ activities (11 mentions):

‘Grey zone’ is one of a range of terms used to describe activities designed to coerce countries in ways that seek to avoid military conflict. Examples include using para-military forces, militarisation of disputed features, exploiting influence, interference operations and the coercive use of trade and economic levers. These tactics are not new. But they are now being used in our immediate region against shared interests in security and stability. They are facilitated by technological developments including cyber warfare.

The definition of grey zone is one of two text boxes, a design feature that puts something up in lights.

The second box marks a big break, ditching 50 years of Australian strategic theology: Australia no longer believes it has 10 years’ warning time of a conventional conflict, based on the time it’d take an adversary to prepare and mobilise for war.

Previous Defence planning has assumed a ten-year strategic warning time for a major conventional attack against Australia. This is no longer an appropriate basis for defence planning. Coercion, competition and grey-zone activities directly or indirectly targeting Australian interests are occurring now. Growing regional military capabilities, and the speed at which they can be deployed, mean Australia can no longer rely on a timely warning ahead of conflict occurring. Reduced warning times mean defence plans can no longer assume Australia will have time to gradually adjust military capability and preparedness in response to emerging challenges.

Lucky is the country that has 10 years’ warning of war. Unhappy is the country that no longer has that comfort.

Order suffers. Coercion rises. Geography is back. War in the Indo-Pacific, ‘while still unlikely, is less remote than in the past’. The update is a sombre accounting.

Some of the Chinese government’s recent policies seem to make little practical sense and the decision to impose its national security law on Hong Kong is a prime example. The law’s rushed enactment by China’s rubber-stamp National People’s Congress on 30 June effectively ends the ‘one country, two systems’ model that has prevailed since 1997, when the city was returned from British to Chinese rule, and tensions between China and the West have increased sharply as a consequence.

Hong Kong’s future as an international financial centre is now in grave peril, while resistance by residents determined to defend their freedom will make the city even less stable. Moreover, China’s latest move will help the United States to persuade wavering European allies to join its nascent anti-China coalition. The long-term consequences for China are therefore likely to be dire.

It is tempting to see China’s major policy miscalculations as a consequence of over-concentration of power in the hands of President Xi Jinping: strongman rule inhibits internal debate and makes poor decisions more likely. This argument is not necessarily wrong, but it omits a more important reason for the Chinese government’s self-destructive policies: the mindset of the Chinese Communist Party.

The CCP sees the world as, first and foremost, a jungle. Having been shaped by its own bloody and brutal struggle for power against impossible odds between 1921 and 1949, the party is firmly convinced that the world is a Hobbesian place where long-term survival depends solely on raw power. When the balance of power is against it, the CCP must rely on cunning and caution to survive. The late Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping aptly summarised this strategic realism with his foreign-policy dictum: ‘hide your strength and bide your time.’

So, when China pledged in the 1984 joint declaration with the United Kingdom to maintain Hong Kong’s autonomy for 50 years after the 1997 handover, it was acting out of weakness rather than a belief in international law. As the balance of power has since shifted in its favour, China has consistently been willing to break its earlier commitments when doing so serves its interests. In addition to cracking down on Hong Kong, for example, China is attempting to solidify its claims in disputed areas of the South China Sea by building militarised artificial islands there.

The CCP’s worldview is also coloured by a cynical belief in the power of greed. Even before China became the world’s second-largest economy, the party was convinced that Western governments were mere lackeys of capitalist interests. Although these countries might profess fealty to human rights and democracy, the CCP believed that they could not afford to lose access to the Chinese market—especially if their capitalist rivals stood to profit as a result.

Such cynicism now permeates China’s strategy of asserting full control over Hong Kong. Chinese leaders expect the West’s anger at their actions to fade quickly, calculating that Western firms are too heavily vested in the city to let the perils of China’s police state be a deal-breaker.

Even when the CCP knows that it will incur serious penalties for its actions, it has seldom flinched from taking measures—such as the crackdown on Hong Kong—deemed essential to maintaining its hold on power. Western governments had expected that credible threats of sanctions against China would be a powerful deterrent to CCP aggression towards the city. But judging by how China has thumbed its nose at the West, and especially at the US and President Donald Trump, this has obviously not been the case.

These Western threats do not lack credibility or substance: comprehensive sanctions encompassing travel, trade, technology transfers and financial transactions could seriously undermine Hong Kong’s economic wellbeing and Chinese prestige. But sanctions imposed on a dictatorship typically hurt the regime’s victims more than its leaders, thus reducing their deterrent value.

Until recently, the West’s acquiescence in the face of Chinese assertiveness appeared to have vindicated the CCP’s Hobbesian worldview. Before the rise of Trumpism and the subsequent radical shift in US policy towards China, Chinese leaders had encountered practically no pushback, despite repeatedly overplaying their hand.

But in Trump and his national-security hawks, China has finally met its match. Like their counterparts in Beijing, the US president and his senior advisers not only believe in the law of the jungle, but are also unafraid to wield raw power against their foes.

Unfortunately for the CCP, it now has to contend with a far more determined adversary. Worse still, America’s willingness to absorb enormous short-term economic pain to gain a long-term strategic edge over China indicates that greed has lost its primacy. In particular, the US strategy of ‘decoupling’—severing the dense web of Sino-American economic ties—has caught China totally by surprise, because no CCP leader ever imagined that the US government would be willing to write off the Chinese market in pursuit of broader geopolitical objectives.

For the first time since the end of the Cultural Revolution, the CCP faces a genuine existential threat, mainly because its mindset has led it to commit a series of calamitous strategic errors. And its latest intervention in Hong Kong suggests that it has no intention of changing course.

China’s Communist Party leaders have long understood the potency of symbols and the power to write history.

It’s why Hong Kong protesters defacing the Chinese emblem with black paint and throwing a Chinese flag into the harbour were such an affront. It’s why many pro-China stalwarts here were so incensed by Hong Kong demonstrators brandishing the British colonial flag. And it’s why a seemingly innocuous question on a high school exam—asking whether Japan had done ‘more good than harm’ to China during the early half of the 20th century—ignited such official outrage that the question had to be pulled from the exam.

I often thought about the Chinese government’s near obsession with their symbols and controlling their historical narrative when considering how the United States has taken somewhat the opposite approach.

Americans largely hate seeing their flag burned at a protest, but the Supreme Court has ruled that flag-burning is a form of free speech protected by the constitution. Athletes choosing to kneel during the national anthem to highlight racial injustice is considered offensive to many, including President Donald Trump, but most Americans agree that such a protest should be allowed.

But the symbols and history of the old Confederacy—the 13 states that rebelled against the government during the Civil War—present a different, more difficult challenge. America only now is coming to a long-overdue reckoning.

Statues and monuments to Confederate generals and politicians are ubiquitous across the south. Military bases are named after Confederate generals. Highways and streets bear the names of the old stalwarts of Dixie. And at some political rallies and protests, Confederate flags seem to outnumber the stars and stripes.

In the wake of the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis policeman in May, and the ensuing nationwide demonstrations against racial inequality, some of these Confederate statues are coming down. They’ve been toppled by activists or relocated to museums. The state of Mississippi finally removed the Confederate battle emblem from its flag. NASCAR, America’s stockcar racing organisation with deep roots in the south, has banned Confederate flags at all its events.

It’s long past time.

As a beginning reporter fresh out of college, I moved to Washington DC and made my first ever trip by car across the Potomac River to Virginia for a story. Passing Arlington National Cemetery, I found myself driving on something called the Jefferson Davis Highway. I knew enough Civil War history to be horrified. Davis was the president of the Confederacy. Sometime later I ended up on Lee Highway, named after the Confederate commanding general Robert E. Lee.

Naming highways after the defeated losers of a civil war would be the equivalent of going to Nanjing, China, and finding a major thoroughfare named ‘Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek Boulevard’.

The difference is that China erases the vanquished. In the US, at least in the south, monuments were erected in their honour. The reasons for this are many, starting with the south being allowed to write its own version of history.

Southerners like to refer to the Civil War as ‘the war between the states’, and the proximate cause is called a dispute over states’ rights. The war, from 1861 to 1865, is exalted as ‘a noble cause’.

All that, of course, is a revisionist view. The war was the result of a southern insurrection by traitors against the legitimate government over one single issue—the southern states’ desire to keep black people enslaved as human chattel. The various euphemisms employed today are all about whitewashing that horrific history.

Why? Because after the defeat of the southern insurrection and the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, many northerners wanted to unify the country again and accept the traitor states back into the fold. There was a brief period called ‘Reconstruction’, during which freed black slaves were supposed to be granted their civil rights and the north would supervise the former Confederate states. But northern politicians eventually lost interest, and the post-slavery south was able to impose a new system of racial segregation known as ‘Jim Crow’, which persisted until the modern civil rights movement of the 1950s.

Many statues honouring Confederate leaders were in fact erected not after the Civil War, but much later, in the 1950s and ’60s, as a show of defiance against integration and black civil rights. The statues, like the flags, were meant to perpetuate the culture of white domination.

In the US, there was never any attempt to ban Confederate iconography or hero-worship of southern generals in the way that, for example, Germany after World War II banned Nazi propaganda and emblems, including the swastika.

Today, the Confederate flag is displayed to show defiance of the government and rebellion against disliked policies. Confederate flags are a fixture at Trump rallies. I was surprised to see armed protestors demonstrating against coronavirus lockdowns in Lansing, the capital city of my home state of Michigan, waving Confederate flags—in the industrial midwest, far from the old Mason–Dixon line that separated north and south.

As much as I find the flag loathsome, and as curious as I am about why supposedly ‘patriotic’ Americans would wave the banner of insurrectionists, I respect their right to wave it. For me, it’s a matter of free speech. Whether someone is carrying a Confederate flag or burning an American one, it’s like kneeling during the national anthem; I may find it distasteful, but I will always support their right to do it.

Where to draw the line between permissible and proscribed, when it comes to historical iconography? It’s a difficult one that many countries are now grappling with. One test for me is whether the expression is individual or public. An individual carrying an offensive flag is exercising their right to free speech. But a statue or monument on public land, or a highway named after a controversial figure, is being supported by taxpayer dollars. If a large portion of the population finds a statue or a highway name offensive, then it seems time for a change.

China’s draconian new law in Hong Kong prohibits many forms of expression once tolerated as free speech. These include banning displays of banners or pamphlets promoting independence, and making use of the phrase ‘Liberate Hong Kong; revolution of our times’ a criminal offence. Since the law became effective on 1 July, Hongkongers have been scrubbing their social media accounts of potential offensive posts, and restaurants and shops have been removing stickers and post-it notes with pro-democracy slogans.

China is also now trying to impose ‘patriotic education’ in Hong Kong schools, in an effort, in Beijing’s view, to eradicate the vestiges of a ‘colonial mentality’ and force young Hongkongers to love the motherland and exalt Communist Party rule. China’s form of instilling patriotism includes erasing atrocities like the Cultural Revolution and the massacre of pro-democracy students at Tiananmen Square.

Banning Confederate flags and monuments, and removing the names of known racists from military bases and the prestigious Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton, is often loudly derided, including by Trump, as part of a ‘cancel culture’ that wants to erase elements of American history. But this change is coming after decades of public debate, a bottom-up grassroots movement for inclusion and equality, and a new national reckoning with injustices of the past.

In China and Hong Kong, the banning of flags and slogans, and the moves to erase history, are being imposed from the top down, by a single party state that wants to solidify its control. It’s how the Chinese Communist Party has managed to stay in power for more than 70 years—by knowing the potency of symbolism, and exercising its power to write its own version of history.

Regional flashpoints are heating up, as we’ve seen with the fatal clash in Ladakh on the India–China border, the protests in Hong Kong and provocative sorties in the airspace over Taiwan and Japan. But the South China Sea may be the most dangerous of all.

Recent developments suggest that China is making even more decisive, and potentially long-lasting, moves to override other countries’ claims in this large and strategically crucial body of water.

Concern is growing that Beijing plans to declare an air defence identification zone over the Spratly, Paracel and Pratas islands. An ADIZ is a region of airspace over land or sea in which the identification, location and control of aircraft are ‘performed by a country in the interest of its national security’. This is not a new idea, of course; China unilaterally declared an ADIZ over the East China Sea in 2003.

Such a declaration would invite much criticism from Southeast Asian claimants, and would certainly be a great worry for Taiwan and Japan. It might also catalyse long-needed unity and solidarity in the regional response to China.

Over the past few months, Beijing has intensified its activities in the South China Sea, causing increased anxiety among its Southeast Asian neighbours.

In early April, a Vietnamese fishing boat was rammed and sunk by a Chinese coast guard ship near the Paracel Islands. That occurred after Vietnam sent a diplomatic note to the United Nations protesting China’s ‘nine-dash line claims’ in late March. There has since been speculation that Vietnam—which has been among the most vocal and active nations in standing up to China in the South China Sea—will pursue international legal action as the Philippines did in 2016.

China also unilaterally declared two new administrative regions in the South China Sea, indicating its desire to devote more manpower and resources to its artificial islands, build additional infrastructure, strengthen its military presence in the area, and permanently formalise its control over disputed waters. And while maritime conflicts are high on Hanoi’s agenda as this year’s ASEAN chair, the move makes clear that China has no intention of working towards a functional dispute management mechanism through ASEAN processes.

The Philippines was also subject to China’s increasingly bold actions in the South China Sea, when a People’s Liberation Army warship readied its weapons to target a Philippine Navy ship. While Manila appears to have forged closer relations with Beijing, there are still indications that it’s prepared to protect its sovereignty. The Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs released a statement in support of Vietnam, expressing ‘deep concern’ about the sinking of the Vietnamese vessel and noting ‘how much trust in a friendship’ can be lost following such incidents. The Philippines’ reversal of its decision to withdraw from the Visiting Forces Agreement with the US and its decision to restart oil and gas exploration in the South China Sea are further promising signs of Southeast Asian resolve.

Malaysia was involved in a months-long standoff with China after a Chinese survey ship entered its exclusive economic zone. But Malaysia’s reaction has been relatively muted, in line with its traditional preference for a low-profile approach on South China Sea issues. At the time Malaysia was also preoccupied with abrupt changes within its government.

Indonesia, which is not a claimant state and has usually kept quiet on the issue, recently sent a diplomatic letter to the UN countering Beijing’s position on the South China Sea. It declared that China’s claims had no standing under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and referenced the 2016 ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration that rejected Beijing’s claim to ‘historic rights’ in the disputed waters. This response demonstrated Indonesia’s resolve in the face of repeated Chinese incursions into its waters and its seriousness about protecting its maritime boundaries.

Even the usually soft-spoken ASEAN has weighed in. At the recent summit, the association’s leaders issued a joint statement stressing the importance of resolving disputes ‘without resorting to the threat of use of force’ and reaffirming the importance of UNCLOS.

China’s stepped-up efforts to assert control over the South China Sea may prove counterproductive for Beijing. The shift to an explicitly offensive posture has already ramped up tensions with the US and increased the risk of miscalculation and escalation in the region. For the first time in years, the US sent three aircraft carriers to the Pacific Ocean. The timing of this show of force was no coincidence and, combined with an increase in freedom-of-navigation operations, indicates how dangerous the situation has become.

China’s relations with its Southeast Asian neighbours also stand to be damaged. Its aggressive behaviour is pushing some states closer to the US and other democratic allies in the region, and it may well prompt them to respond overtly, abandoning the hedging strategy they’ve pursued thus far.

Indeed, the intensification of China’s actions in the South China Sea and the increasing willingness of regional nations to defend against Beijing’s encroachments should motivate Southeast Asian states to act in a united and resolute way.

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria