Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

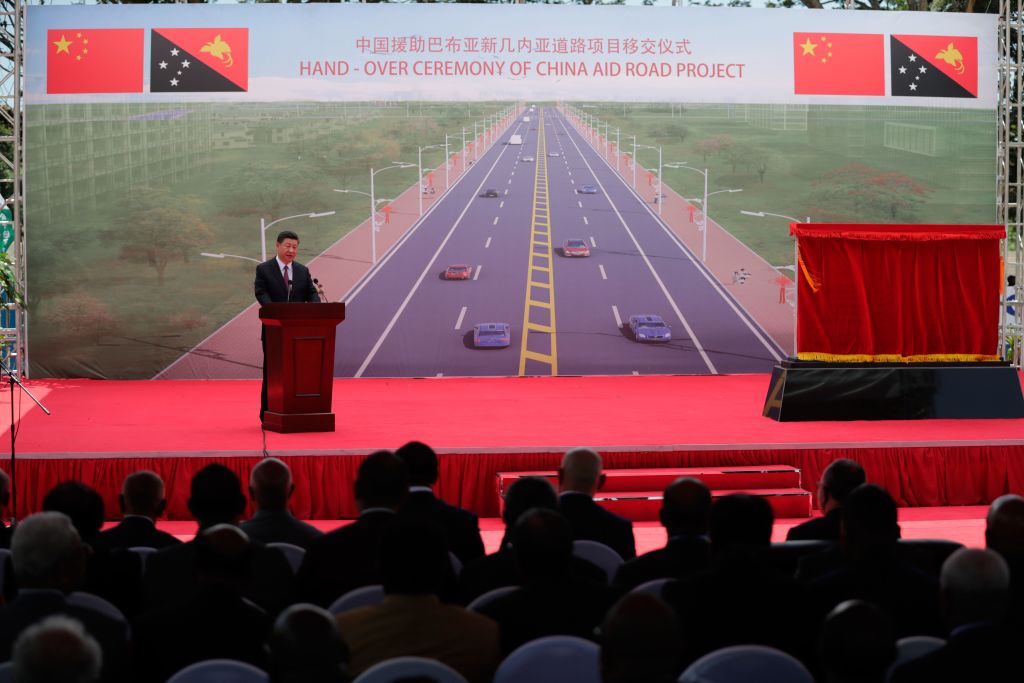

The rapidly deteriorating state of Papua New Guinea’s economy is presenting serious challenges for the PNG government, which is already struggling to finance its 2020 budget.

But another factor looms as an equal, if not more serious, challenge. At a time of fiscal vulnerability, PNG is getting entangled with Chinese debt—which will inevitably involve some difficult decisions for the Australian government down the line.

A series of assessments of the state of the economy by banks and ratings agencies in recent weeks presents a very bleak picture. The PNG budget deficit is now projected to be over K7 billion (A$2.7 billion) in a total expenditure budget of K18 billion (A$7 billion). The PNG government hasn’t yet managed to fully finance the deficit, so it might even be higher than recent projections.

At the same time, there are signs that PNG may be at risk of increasing indebtedness to China.

The state enterprises minister, Sasindran Muthuvel, recently revealed that PNG owes China, principally through the Exim Bank of China, more than K1.6 billion (A$621 million) for communications projects alone—most of which have been carried out by Huawei. The government-owned communications company, Telikom PNG, is running up heavy operating losses which are linked to the projects Huawei has carried out. Its debts are reported to be more than K2 billion (A$777 million).

The loans include almost K1 billion (A$388 million) for the Kumul submarine communications cable linking PNG’s major centres. The project has been widely criticised for neglecting to account for the impact of earthquakes and the cable suffered multiple breaks during a tremor in May last year.

And despite all the promises about lower consumer charges and faster internet delivery, neither seems to have been delivered.

In addition, the K200 million (A$75 million) Exim Bank loan for the PNG national data centre for work carried out by Huawei must also be added to the debt total. The centre is not only a potential security risk, but is virtually non-operational, causing the relevant minister to suggest PNG shouldn’t have to repay the loan.

Then there’s the China-funded PNG national identity document project. It has stalled, with probably just one million of PNG’s eight million citizens having an identity card. Using the excuse of the Covid-19 pandemic, the PNG government has put the project on hold.

So, in the communications area alone, the amount owed to the PRC, principally through Exim Bank, is around K3 billion (A$1.2 billion), much more than official figures suggest.

But communications is just one area in which the China ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ is impacting PNG. The picture looks much worse when road construction, ports and airports are included.

Work is underway on the development of the Kavieng International Airport in New Ireland at a cost of almost K200 million (A$78 million). And work is continuing on the redevelopment of the vital Highlands Highway at a cost of close to K500 million (A$194 million). Both projects are being carried out by Chinese state-owned companies.

And construction of the signature national court complex is running well behind schedule. It’s another project being built by a Chinese company and will cost at least K480 million (A$186 million).

Reports on the quality of the roadwork and other infrastructure projects undertaken by Chinese companies across PNG indicate that the quality of construction is variable.

But it doesn’t stop there.

Some years ago, the Shenzhen Energy Group and Sinohydro were selected by PNG Power—another government-owned entity in poor financial shape—to construct the massive Ramu 2 hydro power project.

The project, which will cost at least K8 billion (A$3.1 billion), has had to be guaranteed by the PNG government under a loan from China.

Such a loan would almost certainly be beyond the capacity of PNG Power to repay and the project has been stalled for at least the last year, resulting in threats from the selected tenderers to cancel it.

The Australian government has been lobbying heavily against the project, and has put forward as an alternative a series of smaller power projects funded by a group of countries led by Australia.

But the Ramu 2 project is not dead. It has powerful backing within the PNG cabinet—and the Chinese ambassador continues to lobby strongly for it.

Late last year, Australia gave the PNG government a loan of around K1 billion (A$388 million), basically to finance the budget shortfall. It has already agreed to delay repayment. And more recently it allowed around K50 million (A$19 million) to be drawn down in cash from the aid budget to help the PNG government out.

If China applies pressure on PNG to make significant repayment on loans running into billions of dollars, the fiscal position will be even worse than it already is.

Australia has rightly been working with the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and other donor countries and agencies on a package that would essentially provide ‘structural adjustment support’ for PNG. But any such package would have tough conditions that might be unpalatable to PNG Prime Minister James Marape and his government ahead of an election in less than two years.

The Australian government is likely to be watching the deteriorating economic and fiscal outlook in PNG with growing alarm.

It also has to watch closely when Beijing starts calling in its extensive loans to the government and government-owned corporations, and pre-empt the kinds of concessions China may try to extract from PNG in return for further extensions or loan forgiveness.

Australia’s own budget deficit and national debt in light of the response to Covid-19 are eye-watering, making any decision to help PNG further very difficult politically, at least for the foreseeable future.

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg ended the prospects of Japan’s Kirin group selling its $600 million Australian Lion Dairy and Drinks business to Chinese dairy firm Mengniu when he gave his preliminary view that the sale ‘would be contrary to the national interest’.

It was a good decision, even if the officials who advise the Foreign Investment Review Board may not have been as clear-eyed as the treasurer was on the matter.

Mengniu’s primary shareholder is the huge Chinese state-owned enterprise China National Oils, Foodstuffs and Cereals Corporation. France’s Danone group also has shares in Mengniu.

Why might the treasurer have made this decision instead of letting a big commercial transaction go through? And who cares if this enterprise is in Japanese or Chinese hands? I can’t read his mind, but the decision logic does seem likely to have had a particular flow.

Neither Kirin nor the Japanese government has been threatening and coercing Australia with trade and economics. They are unlikely to start doing so any time soon.

In contrast, the Chinese government is engaging in public and coercive trade measures against Australian companies to pressure the Australian people and government to stop acting in our national interests. So, not all foreign owners are created equal, despite our government’s ‘country agnostic’ talking points.

Chinese government officials in Beijing and Canberra have made open threats to use trade and economics as weapons against Australia because our government has made decisions that the leadership in Beijing doesn’t like, but which have influenced international debates—from 5G to the Covid-19 pandemic. Wine and barley exports to China have been early and obvious victims.

Much of the recent debate has been about China’s trade power with Australia. However, Australia has leverage in trade and economics too, because we’re a high-quality producer of competitively priced goods and services that China really needs—not just iron ore, LNG and coal.

Food security is a pressing and growing problem for Beijing, as its population ages, as demands from its wealthy middle class increase, and as its arable land becomes less productive because of pollution, development and climate change.

Along with food security, food safety is a priority of Chinese consumers. China’s dairy industry has had safety scandals—from polluted baby milk formula to melamine in liquid milk (Mengniu Dairy was one of the companies involved in the latter scandal).

Aside from the Lion purchase boosting Mengniu’s business, the Chinese Communist Party leadership would see it as making political, strategic and economic sense because it’s about both food security and food safety.

Overall, then, this is more important than a simple commercial transfer of ownership from a Japanese to a Chinese company, particularly if it’s an indicator of further changes in the same direction.

For Australia, the economic benefit from the ownership transfer isn’t clear. In fact, there’s potential for Mengniu to simply not increase prices paid to Australian dairy farmers and other suppliers but instead use its growing market position to keep pressure on prices and take the profits from sales to wealthy middle-class consumers in China.

Leverage on our trade and economic engagement is not a one-way system controlled in Beijing. Frydenberg’s handling of the transaction sends a message that Australia has leverage and is willing to use it. It’s a demonstration that Beijing’s continuing coercion of Australia and Australian companies can have consequences that matter to China, as well as for its companies’ global growth ambitions.

Australia has a long track record as an advocate for free and open trade and investment, so the fact that our economic and trade calculations are changing in the face of Chinese economic coercion is a signal to others trading with China that they too need to reassess their previous policy assumptions.

If Beijing’s decision-makers are as rational on economics as David Uren suggests in a recent Strategist piece, the powerful logic of preventing further deterioration in China’s access to Australia should help reduce Beijing’s willingness to threaten and act against other Australian companies and industries.

Fortunately, the Chinese government’s leaders don’t have to be as economically rational as Uren describes to think more carefully from here.

Even under a ‘limited rationality’ scenario, it’s just possible that the simple benefits to China’s pandemic-hobbled economy from returning to positive engagement with Australia will make more sense in Beijing than insisting on the ‘troubled marriage that is all your fault’ line we heard most recently from Deputy Ambassador Wang Xining.

The other possibility, of course, is that none of this matters as much to Xi Jinping as being seen to be punishing the Australian government as a lesson to others. He and his advisers may see the pressure they’re creating on Australia as empowering advocates for a return to our longstanding policy of increasing economic engagement with China while setting aside strategic differences.

If so, Xi may be discounting four things: the now solid public sentiment in Australia that the Chinese government cannot be trusted to act responsibly; the healthy bipartisan political understanding about the dangerous strategic direction China is taking under his leadership; the fact that coercion has the reverse effect on Australians to the one Beijing seems to expect—it provokes resistance and counteractions, not acquiescence; and that the approach China is taking against Australia and others is hardening attitudes towards Beijing internationally, notably in countries with similar interests and values to us.

So, Frydenberg has been smart in two ways—making a decision on Mengniu’s takeover bid while letting others explain the logic that is most likely to have driven it, and leaving Beijing with the task of joining the dots.

The next steps from Beijing will be clarifying moments, and not just for Australians and Australian policy on China.

In this episode, Alex Joske and Danielle Cave of ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre speak about Alex’s report, Hunting the Phoenix: The Chinese Communist Party’s global search for technology and talent, which examines China’s global recruitment programs for researchers and scientists. They talk about the scale of the programs and how governments can shape their policy responses to them.

ICPC researcher Elise Thomas and intern Albert Zhang then give a rundown on their latest report, which looks at disinformation about a Covid-19 vaccine that emerged from pro-Russian media in eastern Ukraine and managed to make its way across international social media networks.

And the head of ASPI’s counterterrorism program, Leanne Close, speaks to author and researcher Julia Ebner about her book, Going dark: The secret social lives of extremists. They discuss right-wing extremism and Julia details her experiences going undercover to engage with extremist groups and individuals.

Attention on the Chinese government’s recruitment of overseas scientists reached a crescendo when renowned Harvard nanotechnology expert Charles Lieber was arrested and charged with hiding his participation in China’s Thousand Talents Plan in January.

As ASPI’s new report, Hunting the phoenix: The Chinese Communist Party’s search for technology and talent, explains, he is likely only one among more than 60,000 scientists recruited through over 200 talent recruitment programs run by the Chinese government in an effort to gain technology and talent from abroad since 2008.

The scale of these recruitment activities appears to be immense, as are the security risks for targeted countries. For example, uncontrolled technology transfers to China could end up in weapon programs and enable human rights abuses. The economic costs are also high, as valuable intellectual property bleeds out of taxpayer-funded universities and into China, potentially costing revenue and jobs. Yet countries and institutions outside of the United States are only now beginning to forge responses to this problem.

But rather than focusing on the individuals who have joined talent-recruitment programs, Hunting the phoenix describes their structure and recruitment mechanisms, which until now have been poorly understood. These programs are much broader than the Thousand Talents Plan. For example, more than 80% of talent-recruitment programs are run at the subnational level and may attract as many as seven times more scientists than the national programs.

One of the key findings is that the Chinese government has established more than 600 ‘talent-recruitment stations’ around the world. These stations are essentially contractual arrangements between parts of the Chinese government and overseas organisations and companies. The overseas organisations receive up to A$30,000 for general operating costs each year, and large bonuses for each individual they recruit. And numbers are growing. The report identifies 146 in the United States, 57 each in Germany and Australia, and more than 40 each in the UK, Canada, Japan and France.

All countries seek to attract talent from abroad, but there are important and concerning features of how the Chinese state does so. The recruitment programs aim to make deals with individual researchers rather than institutions, which makes it easier for partnerships to fly under the radar. The programs also allow researchers to keep their original job while taking up a second job in China, which can contravene the employment and IP regulations of target universities unless properly managed. Taken together with the quick path China can offer to commercialising research, the incentives for academics are clear.

It’s important to note that many who join the Chinese government’s talent recruitment programs don’t break any rules. They sign a contract to work at a university in China, leave their job and move to China. The flow of talent between countries is a normal feature of the international research community.

However, cases like that of Charles Lieber and others analysed in the report highlight how some recruits are attempting to juggle their original job with multiple positions in China.

Large numbers of recruits may be failing to accurately disclose conflicts of interest and external employment, raising concerns about potential foreign interference and misuse of public funds. In the United States, 54 scientists lost their jobs after the National Institutes of Health raised concerns about potential failures to disclose foreign funding. China was the source of funding in nearly all cases. An investigation by Texas A&M University found that more than 100 of its staff or visiting scholars were linked to Chinese government recruitment programs and only five had disclosed those ties. More than 20 scientists have been charged by the US government for crimes related to talent-recruitment activity, including visa fraud, grant fraud and economic espionage. Entrepreneurship is also an important component of China’s talent-recruitment efforts, and some participants seek to commercialise research in China without disclosing it.

Hunting the phoenix shows that misconduct and hidden technology transfers are a feature of Chinese government recruitment efforts, rather than a problem it’s trying to stamp out. Chinese government agencies that oversee talent recruitment, such as the State Administration of Foreign Experts Affairs, have themselves been implicated in espionage. The recruitment programs incentivise and enable economic espionage. In one case, Chinese intelligence officers used a Thousand Talents Plan scholar to steal aviation technology from the United States.

The Chinese government has failed to acknowledge the concerning activities associated with its talent programs. In fact, its recruitment programs have only become more secretive and covert in recent years.

The Chinese government’s talent-recruitment efforts are global, raising similar concerns in all developed nations. It’s likely that thousands of scientists and engineers have been recruited from the UK, Germany, Singapore, Canada, Japan, France and Australia since 2008. The lack of public prosecutions or misconduct cases linked to talent-recruitment activity in those countries is likely due to the early stage of their awareness of the implications of these recruitment programs.

The good news is that the host-country risks for China’s recruitment programs can often be addressed by better enforcement of existing regulations, backed up by stronger analytical capabilities. Much of the misconduct associated with talent-recruitment programs that has been uncovered to date breaches existing laws, contracts and institutional policies.

But the fact that it still occurs at high levels points to a failure of compliance and enforcement mechanisms across research institutions and relevant government agencies. Governments and research institutions must work together to build both awareness of CCP talent-recruitment work and the capabilities to investigate and respond to it.

The report recommends measures such as increasing resourcing to agencies responsible for compliance and enforcement, integrating public disclosure requirements for foreign funding into all research grant and funding processes, and setting up national research integrity offices to link the efforts of the government and tertiary sectors.

This kind of institutional transparency building is critical to disrupting uncontrolled technology transfers to China and to helping science and technology researchers understand the national-security risks that can lie beneath the surface of China’s talent-recruitment programs.

The arrest of Hong Kong media figure Jimmy Lai on 10 August and the subsequent police raid of the offices of his Apple Daily news company sent a clear signal of how Beijing intends to use the new national security law to bend the population of Hong Kong to its will.

It’s unsurprising that Chinese authorities have Hong Kong’s independent media at the top of their list of targets for the new legislation. Local media coverage of protests in Hong Kong since 2019 not only played a role in sustaining the pro-democracy movement through saturation coverage, but also acted as a constraining influence on the actions of local security services.

If Lai’s arrest proves to be the first step in a campaign by Beijing to throw a shroud over events in Hong Kong—by using the new law’s ambiguously worded offences—then the environment in Hong Kong will change fundamentally.

And, given that events in Hong Kong over the past year have arguably threatened Beijing’s authority, one only has to look at what’s been happening in Xinjiang to predict how the situation might unfold in Hong Kong over the next decade.

Comparisons between Xinjiang and Hong Kong have already been drawn by long-time China watchers, who see Xinjiang as the proverbial canary in the coal mine. Clearly, Hong Kong is not Xinjiang, not the least because of the profile of Hong Kong on the international stage. The influence of Hong Kong’s diaspora communities far exceeds the influence or voice of the global Uyghur diaspora. There’s also a deeply ingrained anti-Muslim sentiment and potentially racism at the heart of Beijing’s treatment of its Uyghurs that isn’t a factor in Hong Kong. And not even the most foolhardy of commentators would suggest that Beijing intends to roll out a Xinjiang-style program of mass internment of Hong Kong’s population.

Nevertheless, comparisons of Hong Kong and Xinjiang are valid because both regions are viewed by Beijing as threats to its authority. In this context, the experiences of the Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslim minorities in Xinjiang provide a cogent case study on how Beijing deals with perceived security threats that might help us understand the potential future of Hong Kong.

In the case of Xinjiang, Beijing has arguably not faced a genuine separatist threat there since the People’s Republic of China absorbed the Second East Turkestan Republic in 1949. Yet, since 2016 it has used the pretext of Uyghur separatism and terrorism to conduct an escalating campaign of persecution that has mutated into a program of genocide involving mass incarceration, forced labour, forced sterilisation of Uyghur women and organ harvesting from detainees.

The protests in Hong Kong over the past year, on the other hand, have rocked the foundations of Beijing’s authority, and the relative moderation of Beijing’s response so far stands in stark contrast to the brutality of its treatment of Muslim minorities in Xinjiang. But Hong Kong is now seeing the start of a more oppressive and brutal response from Beijing.

Importantly, a number of ingredients that were critical to Beijing’s ambitions in Xinjiang are present, or becoming apparent, in Hong Kong.

First, Beijing benefited from pervasive electronic surveillance infrastructure and the ability to deploy an overwhelming physical security presence across Xinjiang. Much of the technical infrastructure required for pervasive electronic surveillance is already in place in Hong Kong. And since the introduction of the new security law, Beijing has also started augmenting its police and security intelligence presence in Hong Kong.

Second, Beijing was able to almost completely curtail the media’s ability to directly chronicle the events unfolding in Xinjiang. Our understanding of the situation in Xinjiang has relied on rare first-hand accounts of witnesses, occasional disclosures of official documents outlining the details of Beijing’s anti-Uyghur program, scrutiny of government contracts and procurement, and satellite imagery.

The paucity of information has enabled Beijing to counter reports of human rights abuses with claims that the reports are fabricated or merely anti-Chinese propaganda, and mount personal attacks against some of the more prominent commentators on the plight of Xinjiang’s Muslims. If the arrest of Lai is the first step in a campaign to extinguish free media in Hong Kong, it won’t be long until Beijing is able to dictate the media narrative in Hong Kong in the same way it does in Xinjiang. To paraphrase the Washington Post’s masthead, human rights die in darkness.

Third, Beijing has been allowed to act in Xinjiang with relative impunity. While some commentators were encouraged by Washington’s decision in early July to target Chinese officials responsible for human rights abuses in Xinjiang with sanctions under the Magnitsky Act, there was no real cause for optimism. The symbolism of these sanctions was largely lost in the noise surrounding Washington’s increasingly toxic relationship with Beijing and ultimately their impact will likely be so inconsequential as to be meaningless.

And even when 22 countries issued a statement condemning Beijing’s treatment of its Uyghur minorities in mid-2019, almost twice as many countries were prepared to commit their names to a register of shame praising Beijing’s ‘remarkable achievements in the field of human rights’.

Chinese investment bought the silence and complicity of a large number of states with regard to the human rights abuses it is perpetrating in Xinjiang. And, despite the strength of the Hong Kong diaspora and Hong Kong’s status as a technologically advanced global financial hub, it’s possible that Chinese money will also buy the silence of other countries if Beijing embarks on a brutal campaign to bring the Hong Kong populace to heel. Already, 53 countries have voiced their support for Hong Kong’s national security law, eerily echoing earlier support for Beijing’s campaign in Xinjiang.

But there is a further aspect to Hong Kong that differentiates it from Xinjiang, and which may prove to be the primary determinant of its future. Hong Kong’s vibrant, innovative and cosmopolitan population has a long tradition of active political and social participation, public mobilisation and debate on issues affecting Hong Kong society.

Hong Kong, along with Taiwan, is a model of Chinese society that is free, vibrant, engaged and wealthy. By its very existence, Hong Kong stands as a direct rebuke to the hyper-intolerant, oppressive and totalitarian regime in Beijing.

Hongkongers, then, present a much more fundamental threat to the enduring authority of Beijing than the Uyghurs of Xinjiang ever have, and will likely be treated accordingly.

The presence of Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei has not been challenged in Papua New Guinea as it has been in Australia, the United States, the United Kingdom and other countries.

Despite a recent embarrassing setback, reported on by the Australian Financial Review, Huawei has positioned itself well to benefit from the likely full or partial privatisation by the PNG government of a number of underperforming state-owned enterprises.

With a loan from Exim Bank of China, PNG commissioned Huawei to build a national data centre in Port Moresby at a total cost of around A$75 million.

PNG Communications Minister Timothy Masiu told the AFR that his government should not have to repay the loan because the data centre is a failed investment, barely works and may have to be shut down.

That will not have gone down well in Huawei’s headquarters, or in the very large and influential Chinese embassy in Port Moresby.

It’s a setback for Huawei, but it remains to been seen whether it will have an impact in PNG beyond one unhappy minister.

The company is well entrenched in the communications sector of Australia’s closest neighbour. It works closely with the state-owned Telikom PNG, an underperforming operation that will probably be first in line for full or partial sale if the cash-strapped government proceeds down that path. Huawei also provides mobile phones and other equipment to operators in the rapidly growing PNG marketplace.

Two years ago, Huawei had another setback in PNG when the Australian government stepped in to block a plan, initiated by Solomon Islands, for the company to build a submarine cable connecting the Solomons, PNG and Australia.

Australia funded the cable’s construction at a cost of around $150 million—a wise investment given the access such a project might provide.

But Huawei was not prevented from building the domestic cable network delivering internet and other telecommunications services to provincial centres around PNG.

That involved another Chinese loan that will have to be repaid. PNG Telikom is believed to have incurred massive debts to China and its capacity to repay them in a very difficult economic environment is just about zero.

In fact, the debt-trap diplomacy strategy pursued by China in developing countries is going to hit PNG hard at a time when its ability to repay Exim Bank of China and other lenders is severely restricted.

Prime Minister James Marape’s government has not yet reached an agreement with an International Monetary Fund–led consortium (which includes Australia) to cover the cost of this year’s budget shortfall. Because the economy is in dire straits, state revenue has collapsed and it’s highly likely that deficit financing for 2020, and probably for 2021 and beyond, will mean substantial cuts to basic services and the public-sector workforce.

It will almost certainly be necessary for the national government to begin the often talked about, but never delivered, sale of state-owned businesses. If that happens, Telikom PNG will be high on the list.

Huawei appears to have a long-term strategy in PNG and the data centre debacle is likely to be but a temporary setback.

The company remains well connected at the highest levels of the PNG government. There’s absolutely no debate in government, parliament or the media about the wisdom of its growing communications presence. Even in PNG’s robust social media environment, debate about its role is limited.

If Telikom PNG is privatised, Huawei will be well placed to join the race to buy it. The dilemma for Huawei might be that the larger communications provider, Digicel, which has a strong presence across the South Pacific and in PNG, might be up for sale as well.

If PNG started a serious sale of its state enterprises, the Australian government would need to watch it closely, and almost certainly get engaged. The most obvious way it could do so would be to provide financial support for Australian companies to buy strategic and viable assets in PNG, and PNG Telikom would have to be one of them.

Another important asset is Air Niugini, but given the state of international travel, buying into airlines might be a hazardous option.

The path towards any asset sales won’t be straightforward, but it might be inevitable despite limited political and community support.

If the sales do proceed, the PNG government will have to secure the highest possible prices and paying top dollar might prove a problem for Chinese entities.

Australia is going to have to play a significant role in any debt financing and structural adjustment program for PNG, though it would be led by the IMF and the World Bank.

Any PNG agreement with the IMF must include a transparent process for asset sales that flow from such a deal. Australia needs to insist on nothing less.

But we will have to be prepared to look seriously at supporting Australian companies’ bids for strategic assets—and that means providing concessional finance. Communications assets must be a priority.

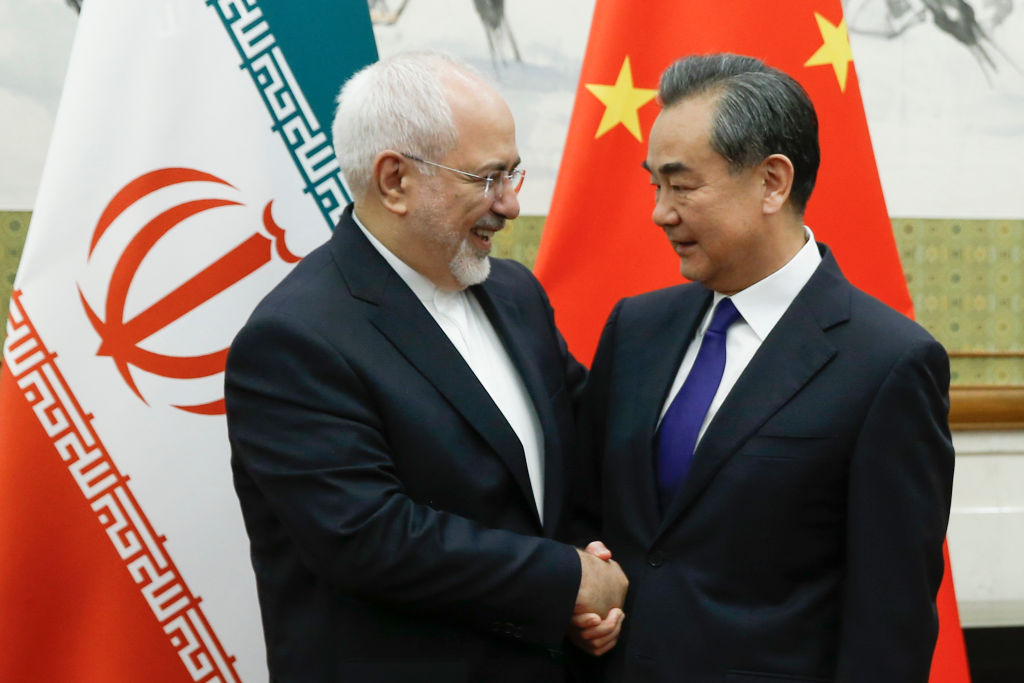

Iran is considering an offer from Beijing to revive an agreement which, combined with an enhanced security and military relationship, could give China a new strategic foothold in the Middle East.

In early July, Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif told Iranian MPs that an Iran–China 25-year strategic cooperation agreement was ‘under consideration’. This is not a new initiative but the renewal and update of a ‘comprehensive strategic partnership’ document signed by Iranian President Hassan Rouhani and Chinese Premier Xi Jinping in Tehran in January 2016.

Few details about the 2016 partnership and the 17 accords which Xi also signed then were ever disclosed. Reportedly, the document was a roadmap for upgrading the bilateral relationship and involved some US$600 billion in two-way trade and investment over the following 10 years. Iranian exports to China were identified as primarily oil, gas and other petrochemical products. China is Iran’s major trading partner and oil is Iran’s primary export to China. Chinese investment in Iran would focus on energy, manufacturing and transportation with road, rail and port projects linked to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The implementation of the partnership and related investment was dependent on the lifting of global sanctions against Iran and was timed to occur shortly after the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) took effect on 16 January 2016.

China appears to have put much of the 2016 agreement on hold after signing. Its principal reason would have been the need to work through the complexities of its relationship with the US, especially after Donald Trump’s election as president and given his hostility to the JCPOA. That became even more complex after the withdrawal of the US from the agreement in May 2018 and its imposition of unilateral sanctions.

Zarif has so far disclosed little detail about the renewed agreement. From information available so far, in addition to trade and investment, it also includes security, military and intelligence cooperation. Two-way trade and investment is valued at US$400 billion, with China investing some US$280 billion in Iran’s energy sector and US$120 billion in transport, telecommunications and manufacturing. A major mutual benefit is China’s guarantee to buy Iranian oil for 25 years, reportedly at a discount price, and Iran’s guarantee to supply it—assuming there’s sufficient long-term stability in the Middle East to allow that to happen.

For Iran, the renewed partnership would provide a significant and desperately needed economic lifeline that it would hope would circumvent crippling US sanctions. Bilateral offset financial arrangements would enable the trading of Iran’s major export resource, oil, without involving the international banking and financial system. Iran’s economy would also benefit significantly from upgraded and new industries, and the jobs they’d create.

For China, the multiple benefits would include the long-term guaranteed supply of oil at a discounted price, the use of Iran as a hub to progress the BRI land transportation corridor between Western China and Turkey, and marketing and manufacturing opportunities for Chinese goods. That would happen, in many cases, at the expense of the Europeans, who are severely constrained or intimidated by the US sanctions. This would demonstrate that, despite its tensions with the US, China is still able both to successfully pursue its geopolitical and economic interests and to secure this new strategic foothold.

The timing of Zarif’s announcement, presumably agreed to by the Chinese, was undoubtedly calculated to rattle the US cage, and especially to unsettle Trump this close to the November presidential elections. One major message from Iran is that it can survive, despite Trump’s ‘maximum pressure’ campaign to force regime change.

Responding to Zarif’s announcement, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said in an interview on 2 August that China’s action would ‘destabilise the Middle East’. He said arms and money from China would enable Iran to continue as ‘the world’s largest state sponsor of terror’ and, particularly, to put Israel, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates at risk. These three countries were singled out because of their growing relationships with China, and the pressure they could put on China to limit the scope of its agreement with Iran.

China and Iran may hasten slowly to implement the agreement. Both are likely to hold back on many detailed aspects until the outcome of the US presidential election is known. Critical considerations for Iran will be whether the US rejoins the JCPOA, and, if so, under what conditions, and whether US sanctions will be lifted.

Iran also will reject any aspect of an agreement with China that suggests any ceding of sovereignty of land or major national resources, or any potential debt trap, as has occurred with other countries. Strict boundaries of sovereignty are enshrined in Iran’s constitution. Iran also will insist that any new infrastructure projects employ Iranian labour and are not, as occurs elsewhere, outsourced to imported Chinese labour.

China’s political, economic and strategic interests in the Middle East are very much regional, and Beijing will be careful not to alienate others and prejudice its broader interests through its dealings with Iran. It will heed representations by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, other Gulf states and Israel, and seek to strike an acceptable balance of respective interests.

On 6 August, Al Jazeera cited Indian media reports that India’s relationship with Iran may be a casualty of the renewed agreement with China. The report claimed that Iran had dropped plans for India to build a railway line between the port city of Chabahar and Zahedan, near the Afghan border. When completed, the project would have provided India with a trade route to Afghanistan and Central Asia. It would also have competed with China’s proposed trade to these countries along BRI-upgraded routes through Pakistan.

Pending clarification of the Indian reports, it seems unlikely that Iran would sacrifice its longstanding relationship with India. As for China, it will seek to balance its interests.

China has dominated the world’s supply of rare-earth elements for decades. Over the past year, however, there has been a growing recognition among the US and its allies (including Australia, South Korea, Japan and India) that sources of critical minerals outside of China need to be secured and that solutions need to be driven by governments rather than market forces, particularly since demand for these materials will skyrocket in the near future.

Recent tensions in the Australia–China relationship have made the need to diversify rare-earths production even more pressing. China currently produces 90% of the world’s rare earths, so its dominance won’t be shifted overnight. This underscores the urgency for Australia and its allies to minimise the risks of over-reliance.

One of the greatest challenges for rare-earths projects, particularly compared to other key Australian exports such as iron ore and coal, is getting upfront financing. Investment is spread thin among a plethora of small investors, creating barriers to market entry for substantial projects. This creates risks that are prohibitive for single investors in the absence of government backing. The scale of the investment problem suggests that allied governments need to work together on providing financing for exploration, mining and processing if they are to develop adequate new supply chains.

There have been promising developments on the domestic front. Defence Minister Linda Reynolds signalled the possibility of increased government support to get rare-earths projects off the ground, considering the immense value they hold for defence applications. Each of Australia’s F-35 fighter jets, for example, contains 417 kilograms of rare-earth elements; most technology applications require only a minute amount. China recently sanctioned Lockheed Martin, restricting its access to the rare-earths supplies needed to produce key parts. Actions like this accelerate the need to take an alliance-based approach.

Elsewhere in government, the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources released a critical minerals strategy last year and established the Critical Minerals Facilitation Office. These are steps in the right direction, particularly if there’s close collaboration with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade as well as Austrade to tap into their wealth of knowledge on promoting trade opportunities and acting as a facilitator. But in the face of the increasing supply-chain risk, there needs to be more decisive action.

A roadblock to greater allied cooperation right now is the political situation in the US. There have been rumblings among some Republican members of Congress that government funding and support should be given only to US companies. For a commodity like rare earths, this is not a viable or appropriate path to take. China’s strength in rare earths comes from its grip on both upstream and downstream processes. While one ally may not be able to assume all the risks of funding and establishing rare-earths projects, they can mitigate these risks by working together.

Rather than just focusing on securing supply locally, the US should move towards incorporating its local fabrication into a broader international strategy of close cooperation. When Japan’s supply of rare-earth minerals was cut off by China in 2010 as bilateral relations deteriorated, it pursued a strategy of international cooperation to deal with the crisis. We are not at crisis point yet, but we shouldn’t allow it to get to that stage before pursuing a similar strategy and consolidating a joint allied approach.

Some of this cooperation is already happening. Lynas, an Australian-owned company that runs one of the most significant rare-earths mining projects outside of China, has received support from international counterparts, including an initial investment of US$250 million from Japan in 2010. More recently, Lynas has partnered with US company Blue Line to build the first facility for processing heavy rare earths outside of China, located in Texas. This is a sign that roadblocks in the US political system aren’t going to be as hard to overcome as originally thought.

Australian rare-earths miner Arafura Resources is piloting a project that will see its minerals processed in Colorado in a partnership with US company USA Rare Earths. Arafura is ready to supply significant amounts of key rare-earth elements, including neodymium and praseodymium, which are used in magnets and aircraft engines, but needs greater visibility and investment to do so. Other projects in Australia face similar hurdles.

These partnerships should be encouraged through advocacy by Australian government officials in strategic locations. Australia’s ambassador to the US, Arthur Sinodinos, indicated that he has been advancing the Lynas case with the US Congress and the White House. This support needs to be broadened and include a push against US-only policies on rare earths, which do not serve the wider agenda of minimising over-reliance on supplies from China.

For its part, the Australian government should look towards becoming an investor in this sector if it is serious about developing a rare-earths supply chain independent of China. Looking even deeper into the future, investment should be made in exploring more sustainable ways of processing rare earths so the country that’s hosting processing facilities doesn’t bear the environmentally destructive impacts of processing.

Australia and close allies on this issue are at a critical juncture. The aftermath of Covid-19 will have far-reaching impacts on the global economic situation but also offers the opportunity to remake vital supply chains. Securing the rare-earths supply chain through investment featured prominently in the recent joint AUSMIN statement, signalling its importance to the US–Australia relationship. But more robust advocacy is needed, and Australia should now take the lead in convening a high-level meeting with key allies to kickstart viable alternatives for rare-earths supplies.

Indonesia appreciated being comprehensively briefed on Australia’s recent defence strategic update before it was announced, says seasoned diplomat and politician Dr Dino Patti Djalal.

The former deputy foreign minister, who now heads the Foreign Policy Community of Indonesia think tank, told ASPI’s online ‘Strategic Vision 2020’ conference that the world was living in ‘a hot peace environment’ with relations among the major powers deteriorating and many potential flashpoints.

Interviewed by journalist Stan Grant, Djalal said he was very pleased that Australia explained its plans to Indonesia. He said that contrasted dramatically with the 2011 announcement that Australia would host US marines in Darwin.

He remembered well being with President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono in Hawaii when journalists asked them what they thought about the US sending marines to Darwin. ‘He looked at me and I had the stupidest look on my face. We did not know about this. We were not told and consulted by the Americans or by the Australians. That was a big lesson.’

Djalal said it was important that the update contained no suggestion that Indonesia was a threat to Australia, ‘Because that was always there in the past. Somehow, Indonesia is seen as some kind of a threat.

‘But I think this document makes it clear that Indonesia is a strong partner for Australia in addressing security issues in the region.’

He said Indonesians were not comfortable seeing defence spending rising around them, as with record levels in the US. ‘We don’t like to see hot peace combined with some sense of an arms race.’

Indonesia favoured soft power and diplomacy. Australia and Indonesia could cooperate on peacekeeping, Djalal said.

Indonesia did not intend to spend more on defence, especially with the pandemic. ‘We are going to need a lot of resources for economic and cultural development’, Djalal said.

Military development had to be accompanied by confidence-building measures, and that was not happening.

On Indonesians’ view of Australia, Djalal observed, ‘I’m out of government, so I can say this, but there’s still some wild conspiracy theories about Australia within the Indonesian body politic.’ Many Indonesians blamed Australia for promoting East Timorese independence. Some felt the deployment of US troops to Darwin was part of some bad strategic design towards Indonesia ‘which obviously is not the case’.

Indonesians loved conspiracy theories, Djalal said. ‘There’s still a bit of that, but the important thing is that the overall structure of the relationship now has changed. The feel between the leaders, the relations between the institutions, the degree of strategic trust between the two sides, this is unlike anything that we have ever seen before in terms of Indonesia–Australia relations.’

That could be affected by issues, he said, as when he discovered via Wikileaks that he and his president were among Indonesians being spied on by an Australian security agency.

At the same time, many Australians were unaware that Indonesia was a thriving democracy.

Now, he said, there was a ‘psyche of partnership’ between Indonesia and Australia. Of all Western countries, Australia knew Indonesia best and had the most invested in having good relations with it.

Indonesian and Australian diplomats worked well together, Djalal said. When he was ambassador to Washington, his best partner was Kim Beazley. ‘Indonesian and Australian diplomats always call each other. Always go to coffees and discuss issues and how to work together.’

This year, Djalal was asked which country Indonesia had grown closer to in the past five years and he responded, ‘China.’

He explained that while relations between Indonesia and China ‘froze’ decades ago, they had improved to the point where China was now Indonesia’s largest trading partner and export market. ‘Chinese diplomats are very active in Indonesia’, he said. Many Chinese tourists visited Indonesia each year and there were now more Indonesian students studying in China than in the US. ‘The number one is still Australia, but China is second after that.’

Ministerial consultations were routine and frequent, Dijlal said. ‘So, I think relations with China have dramatically and significantly intensified, particularly in the last five years or so.’

Dijlal said the driver was economic. China moved very fast on trade, he said. ‘Two decades ago, they were nowhere to be seen, but now they’re one of the biggest investors in Indonesia.’

The relationship was multidimensional and had varying levels of intensity. ‘But if you look at the metrics economically and politically, these are two different things. The Chinese have some difficulties in terms of public reception in Indonesia—the Chinese workers, for example. And then politically on the Natuna issue.’

Indonesia has named the area around its Natuna Islands the ‘North Natuna Sea’. This body of water embraces the southernmost part of the South China Sea and lies within the ‘nine-dash line’ which Beijing says marks out its territory.

Djalal said China’s claim over those waters had raised serious discomfort in Indonesia.

Grant noted that an Indonesian naval vessel had, in 2016, fired warning shots to drive Chinese fishing vessels away from the islands. Djalal responded that this was something new in the last five years. ‘But before that, the Chinese tended to be shy’, he said.

‘But then after 2014 onward, the Chinese seem to be pushing it to our face that, “Hey, we got some claims, they may be overlapping within the nine-dash line”.

‘Our position is very clear that there’s no need to negotiate. There’s no dispute because we don’t recognise the Chinese claims. We don’t recognise the nine-dash line.’

Indonesia did not believe China’s claims were consistent with international law. ‘The one thing that’s different is that the Chinese seem to be more assertive and pushing that issue into our diplomatic relations, but we’re holding tight to our position that we do not recognise that there is an overlap’, Djalal said.

‘With regard also to the rest of the South China Sea, there is a pathway to its resolution or its management through the discussion on the ASEAN–China code of conduct, which is now going on.

‘We don’t support any claims by the claimants and we want peaceful negotiations among them. We want them to exercise self-restraint, not just China but also the other ASEAN claimants, and we want to finalise the code of conduct negotiations.’

Djalal said Indonesia, like other ASEAN nations, had a lot invested in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea because its national territorial structure was embedded in that convention.

‘But this has added urgency now that you have more maritime disputes. And with China, again, pushing the nine-dash line strongly and more assertive behaviour, there needs to be a basis of understanding on how to move forward with this.’

The UN convention provided very clear rules and China had agreed to them, so that was the best basis on which to move forward, he said.

Asked about rising tension between the US and China, Djalal responded that as a Southeast Asian, he was not comfortable with Washington’s tone on China. President Donald Trump was very harsh on China. ‘We have our differences with China, but I think the tone from the US, I’m not comfortable with. I think many Southeast Asians find it disagreeable as well, even though we don’t say it out loud.’

Australia’s position on China had also become harsher, Djalal said. ‘I think there’s a tendency at China bashing in certain quarters in the Western world. This is qualitatively different from how Southeast Asians see China. So, I think that needs to be recognised.’ He said greater finesse was needed in dealing with China.

Djalal said that if Joe Biden won the US election, he would be tough on China but his administration would not play such a strong blame game and its approach would be more sophisticated.

In this episode, Tom Uren of ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre speaks to Sean Duca from cybersecurity company Palo Alto Networks about Tom’s report examining how internet service providers can defend the undefendable. They discuss how ISPs can do more to protect users from online threats.

Louisa Bochner and Elise Thomas from our cyber team then discuss what the future might look like for multinational tech companies operating in Hong Kong and the challenges they face as China’s Great Firewall descends on HK.

And The Strategist’s Brendan Nicholson speaks to the head of ASPI’s defence, strategy and national security program, Michael Shoebridge, about the increasing value being placed on trust globally, and the deficit in China’s trust account with the world.