Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

US President Joe Biden’s first international crisis will likely be over the future of Taiwan. Beijing has been positioning for this outcome for months by steadily increasing military pressure against Taipei.

The People’s Liberation Army Air Force on Saturday dispatched what the Global Times gloatingly called a ‘bomber swarm’ of 13 combat aircraft into Taiwanese airspace just south of the island. This was much larger than previous sorties and included eight long-range H-6K bombers.

The US State Department called on China to stop ‘intimidating its neighbors’ and stated its ‘rock-solid’ commitment to Taiwan’s defence. In response, China deployed 15 combat aircraft to the same region on Sunday. ‘Sooner or later, these fighters will appear over the island of Taiwan’, said a Global Times editorial.

Since Saturday the US aircraft carrier Theodore Roosevelt and an escort strike group of ships have been exercising in the South China Sea, continuing a large-scale US presence in the area for the past six months. These manoeuvres point to a significant increase in regional tensions. Beijing is determined to establish and maintain a higher military tempo around Japan, Taiwan and the South China Sea. Xi Jinping is testing Biden’s resolve.

In my view—this is a judgement, not a demonstrated fact—Xi thinks he can exploit a window of opportunity created by Covid-19 and the change of US president to accelerate China’s ambition to take over Taiwan.

The Chinese Communist Party’s objective is to have Taiwan under its control by 2049, the centenary of the party’s takeover in Beijing. Xi won’t be around then, but in 2021 he has built a military already dominant in the Taiwan Strait and faces a temporarily weakened US focused on other priorities. Does Taiwan matter as much to Biden as cutting a paper deal with Beijing on climate? Xi intends to find out.

What’s clear is that Xi has done everything he can since the Covid outbreak, readying the PLA for a Taiwan contingency and building nationalist enthusiasm for the endeavour. Xi has nothing to lose. If, as is probable, the US stands firm with Taiwan, Xi can revert to the 2049 timetable. If Biden blinks, Xi might just commit a military blunder of globally disastrous proportions.

Thus far the Biden administration has looked prepared and like it is intending to continue Donald Trump’s overt support of Taiwan and more active military role in the South China Sea. China will keep pressing for ways to weaken US determination on the defence of Taiwan. Welcome to the new normal for Indo-Pacific security. Military activities that in past years would be front-page stories about an impending crisis now barely rate a mention.

Disappointingly, our Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade did not protest Beijing’s sabre-rattling over the weekend, even though at the AUSMIN summit last July Australia and the US pledged that ‘recent events only strengthened their resolve to support Taiwan’.

DFAT is no doubt thinking through what that means. It should hurry up as the pace of events is quickening. Whatever Biden does about Taiwan, he will expect Japan and Australia to be there. There is no exit strategy from our own region.

Monday saw a significant announcement from Defence Minister Linda Reynolds of a $1 billion investment into ‘advanced guided weapons to enhance Australia’s maritime security’.

This is not new money but the first approved spend of up to $24 billion allocated in the July 2020 force structure plan for ‘Maritime Guided Weapons’.

This is an important and welcome development. It shows that Defence is hastening to add new range and hitting power to its arsenal as other countries, primarily China, do the same.

The intention is for this investment to begin producing results by ‘mid-decade’, a quick schedule given that the task is not just to buy the weapons but to integrate them onto a range of ships. The aim is to identify and develop joint-production options, most likely with the US. It has been decades since Australia has been in the strike-missile production business, but we have demonstrated the industrial capability with our Nulka active missile decoy, used by the US Navy.

In a conflict, missile stocks will rapidly deplete. If Covid-19 taught us anything, it’s that we must boost domestic production in many areas, but especially the war stocks used by the Australian Defence Force.

Just as was the case with the F-35 joint strike fighter, a joint production effort on a range of missiles gives us access to a wide range of US (and possibly European) science and technology, cements closer alliance cooperation and makes practical military sense for our forces.

Initial investments will focus on upgrades to the next generation of weapons already in service. The thinking is also to identify options for jointly developing new weapons including a sea-launched weapon able to hit land targets at ranges of up to 1,500 kilometres, perhaps a cruise missile.

Rather than go to government with individual missile proposals, Defence is bundling a series of weapons into the one program. Again, this makes sense. We should look to develop the ability to fire weapons from many different types of platforms, drawing on shared technology and support systems. Could this even extend to the navy thinking about using the new long-range anti-ship missile just bought for the air force? Absolutely it should.

A mid-decade rollout of new missile capabilities means that these weapons will be fielded on our current ships and submarines, not the exquisite beauties we’re planning to launch in the 2030s. Thankfully, the government has got the message that Defence isn’t just a subset of industry policy. The essential task at this time is to think about the military challenges Defence will face in the short term.

It’s possible that many Australians may be more comfortable thinking of their military handing out sweets to children in the relatively benign peacekeeping and stabilisation missions of the 1990s. Those images were far from the whole story and they are even further from our strategic world today.

These latest military manoeuvres around Taiwan are, in fact, the emerging front line of Australia’s defence.

Originally published 3 July 2020.

Hong Kong’s first handover to China, in 1997, came with fireworks, lion dances and a mood of cautious optimism that this former British colony would enjoy ‘a high degree of autonomy’ for at least the next 50 years.

Just 23 years later, Hong Kong’s second handover to China—punctuated by a draconian new national security law that proscribes much protest activity and free expression—has seen fearful citizens deleting their Twitter accounts, political parties disbanding, and some activists and ordinary people planning to flee abroad. The optimism of 1997 has been replaced by a sense of foreboding and dread.

In a fitting coda, Beijing’s Communist Party rulers chose the exact anniversary of the handover, midnight on 30 June, to impose their new security law on Hong Kong and unveil its strictures on an unwilling population. After 23 years, China seems to be publicly affirming that the ‘one country, two systems’ experiment has failed and that Hongkongers were not sufficiently imbued with a patriotic love of the motherland and its authoritarian communist one-party system.

Now Hongkongers who had enjoyed a wide range of freedoms and a tiny taste of democracy will be subjected to the same sweeping constraints on their liberties as any Chinese citizen living on the mainland.

Over the past month, the new national security law was drafted behind closed doors in Beijing with no input from Hong Kong officials or citizens, who were not even allowed to see the text until a few minutes before midnight on the day it took effect. There was still some small hope that the law might not be as sweeping as some here feared, perhaps tailor-made for Hong Kong owing to this city’s special history and common-law traditions. Various leaks in the media in recent days appeared designed to assure people that their daily lives would not be greatly affected.

But the final text of the law was more severe and more detailed than the most optimistic here envisaged. Many when they saw it were aghast—shocked, they said, but not surprised.

The law establishes an entirely new infrastructure in Hong Kong to enforce a national security regime. Beijing will set up a national security agency in Hong Kong which will operate independently as it sees fit. China’s agents operating here, with special ID cards, and their cars, ‘shall not be subject to inspection, search or detention’ by local Hong Kong police. They are above the law.

Hong Kong will set up its own separate national security committee, chaired by the chief executive and including a ‘national security adviser’ appointed by Beijing. Its work will remain secret and not subject to judicial review. The law specifies that Beijing’s national security adviser will attend meetings of the committee.

The Hong Kong Police Force will establish its own national security department to collect intelligence and conduct operations. The law gives police wide powers to conduct searches, eavesdropping and surveillance without court oversight and to order people to turn over their electronic communications, and it appears to suggest that internet service providers must cooperate with probes. The law compels suspects to ‘answer questions’ and turn over information, although Hong Kong law gives people a right to stay silent.

The law also says that when there’s a conflict between this new edict and Hong Kong’s existing laws, the national security law takes precedence.

The law sets up a new section in the Justice Department to prosecute national security cases, and trials can be conducted entirely in secret, without a jury, and without the presumption of bail. Serious or ‘complex’ cases can be tried in mainland China.

The law says the Hong Kong government will ‘strengthen public communication, guidance, supervision and regulation’ of national security matters, including those relating to ‘schools, universities, social organisations, the media, and the internet’.

The law vaguely defines four categories of national security offences—secession, subversion of state power, terrorism and collusion with a foreign country. Appearing in Washington DC to advocate for sanctions against Hong Kong or ‘provoking hatred towards the central government’ are all now considered national security law violations.

Penalties for national security offences range up to life imprisonment, although a person who ‘conspires’ with a foreign country ‘shall be liable to a more severe penalty’. The Hong Kong justice secretary told a press conference on 1 July that if a suspect were handed over to mainland authorities to face trial, Hong Kong would have no say in whether the death penalty was imposed.

In a sweeping claim of extraterritoriality, the law also says it will cover offences ‘from outside the region by a person who is not a permanent resident of the region’.

The vagaries of the law for now leave it to the local Hong Kong police to interpret and enforce it. Their actions on 1 July—the handover anniversary, when activists traditionally stage mass protest rallies—showed that the police are taking an expansive view, arresting people for carrying flags promoting Hong Kong independence.

Police raised banners warning demonstrators that chanting the slogans and displaying the flags that had become a staple of the last 12 months of protest could now be considered a national security violation.

‘The law is so broadly written it could include almost any form of behaviour, such as waving an independence-themed flag today’, one longtime resident told me.

This is not the end of Hong Kong. It remains a global financial centre, its stock market is still the world’s largest and more capital is set to flow in if Chinese ‘red chip’ companies forced to delist from the New York Stock Exchange decide to relocate here. Multinationals whose business operations focus mainly on China’s massive market would be reluctant to decamp for faraway Singapore. Taipei and Tokyo are making overtures to lure businesses and hedge funds, but neither is as attractive an international English-speaking base as Hong Kong.

But it is the end of Hong Kong as we knew it. I was recently reminded how when I would leave after a lengthy reporting trip in China and cross the border into Hong Kong, I would almost literally feel a breath of fresh air. Unlike the mainland, reporting here was easy. People were willing to talk and express their views strongly. They gave you their names to be quoted. You didn’t have to hide your notebooks or constantly be looking over your shoulder if you pulled out a camera for a photo. Here I did not have to use multiple sim cards and disposable ‘burner phones’ to meet with sources.

That is all now changing. With the new law and the new national security infrastructure, Hong Kong now is becoming like every other mainland city under an authoritarian police state. Citizens scrubbing their social media accounts and scraping pro-democracy stickers off their shops is a sad but telling sign.

The Hong Kong we knew is dead. This is the new normal.

With President-elect Joe Biden set to take office on 20 January, there’s little time to formulate a China policy, though it’s clear his administration’s approach to Beijing could have long-term implications for stability and peace in Asia. Unquestionably, the People’s Republic of China’s escalating aggression towards Taiwan will be the administration’s greatest strategic challenge.

Decisions made by the Biden administration will likely play a role in determining whether war between China and Taiwan becomes a reality and the lengths to which Taiwan feels it must go to defend its freedom.

Two years ago, President Xi Jinping publicly declared that China would use force to ensure Taiwan’s reunification if it refused to go peacefully. Since then, the People’s Liberation Army has expanded its harassment and testing of Taiwan’s defences through naval, air and cyber aggression.

For many Taiwanese, the recent crackdown on Hong Kong offers a window onto what may come if Taiwan reunifies with the mainland. It should come as no surprise, then, that support for reunification is at an all-time low among Taiwanese, with around 90% in opposition.

Weak security guarantees from the United States, coupled with escalating aggression from China, may soon present Biden with a Taiwan that believes its only option for survival is to take a page from the Israeli playbook and restart a covert nuclear weapons program. When Taiwan went down that path between 1967 and the late 1980s, the government in Taipei ultimately backed away from nuclear weapons because it appeared China was liberalising and heading toward democratisation.

That is certainly no longer the case. Xi is proving a better authoritarian than any of his post-Mao predecessors, and the 2018 decision of the National People’s Congress to remove term limits enables him to remain president and party chair indefinitely.

According to China expert Michael Pillsbury, author of The hundred-year marathon, the Chinese Communist Party intends to integrate Hong Kong and Taiwan back into China in time to achieve ‘Middle Kingdom’ status by 2049—the centennial of the CCP’s victory over the Guomindang in the Chinese civil war.

For many of the China experts on whom the Biden administration will rely for advice, working collaboratively with China is a tenet of the faith that cannot be questioned. They also see a policy of ambiguity concerning US security guarantees with Taiwan as essential.

However, as the PLA rachets up pressure on Taiwan to reunify, Taiwan’s president, Tsai Ing-wen, and her successor will likely find themselves in a position where they must take whatever steps are necessary to ensure the continued independence of a free and democratic Taiwan—either in coordination with the US or independently.

Taiwan’s leaders sensed the urgency to develop their own nuclear capability once already because of the normalising of relations between the US and the PRC. During the 1970s, Taiwan produced plutonium for its indigenous weapons program. While plutonium production was halted because of American pressure in 1976, the military government in Taiwan continued with its secret nuclear weapons program until the 1980s, which included a successful nuclear reaction.

Taiwan is already a latent nuclear power. The move to nuclear weapons would not take long given its current materials and technical capacity.

Taiwan already has two operational nuclear power plants on opposite ends of the island that could produce plutonium. It could use a ‘Japan option’ of enriching its radioactive materials for weaponisation in a short timeframe.

Would a nuclear-armed Taiwan deter the PRC from an invasion? The use of nuclear weapons by a nuclear-armed Taiwan would certainly make an already difficult invasion for Xi and the PLA more costly. History suggests that once Taiwan has nuclear weapons, the PRC will become much less aggressive towards it—making the development of nuclear weapons more attractive.

Tsai’s Democratic Progressive Party, despite its tense relations with the mainland, represents the anti-nuclear movement within Taiwan. However, views change when survival is at stake. It is not a bridge too far to suggest that a reluctant Biden administration and an aggressive Xi might lead Taiwan to see the utility of a nuclear arsenal.

It’s also worth noting that the US has never invaded a nuclear-armed adversary—a fact not lost on the Taiwanese.

Many China experts in the American foreign policy community will dismiss the warning that Taiwan might restart its covert nuclear weapons program. This is because too few American China experts understand the escalating pressure Taiwan faces from Xi’s China.

The Biden administration has time to devise a policy that ensures Taiwan’s security while discouraging the pursuit of nuclear weapons. However, half measures, ambiguity or doing nothing is no longer an option. Taiwan will protect its freedom with or without America’s help.

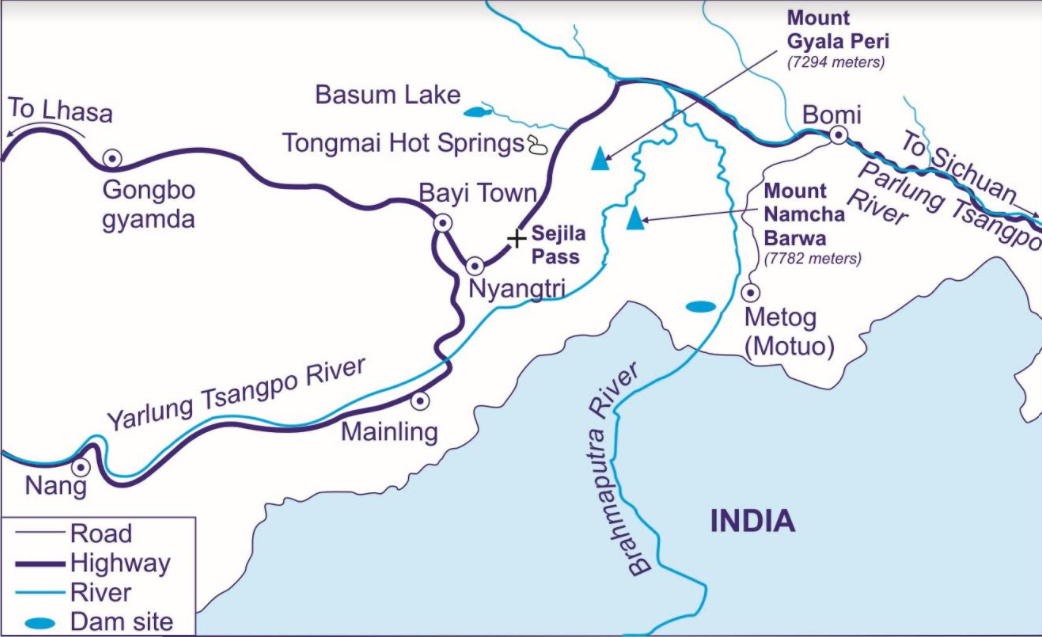

Even after Asia’s economies climb out of the Covid-19 recession, China’s strategy of frenetically building dams and reservoirs on transnational rivers will confront them with a more permanent barrier to long-term economic prosperity: water scarcity. China’s recently unveiled plan to construct a mega-dam on the Yarlung Zangbo River, better known as the Brahmaputra, may be the biggest threat yet.

China dominates Asia’s water map, owing to its annexation of ethnic-minority homelands, such as the water-rich Tibetan Plateau and Xinjiang. China’s territorial aggrandisement in the South China Sea and the Himalayas, where it has targeted even tiny Bhutan, has been accompanied by stealthier efforts to appropriate water resources in transnational river basins—a strategy that hasn’t spared even friendly or pliant neighbours, such as Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Nepal, Kazakhstan and North Korea. Indeed, China hasn’t hesitated to use its hydro-hegemony against its 18 downstream neighbours.

The consequences have been serious. For example, China’s 11 mega-dams on the Mekong River, Southeast Asia’s arterial waterway, have led to recurrent drought downriver, and turned the Mekong Basin into a security and environmental hotspot. Meanwhile, in largely arid Central Asia, China has diverted waters from the Illy and Irtysh rivers, which originate in China-annexed Xinjiang. Its diversion of water from the Illy threatens to turn Kazakhstan’s Lake Balkhash into another Aral Sea, which has all but dried up in less than four decades.

Against this background, China’s plan to dam the Brahmaputra near its disputed—and heavily militarised—border with India should be no surprise. The Chinese communist publication Huanqiu Shibao, citing an article that appeared in Australia, recently urged India’s government to assess how China could ‘weaponise’ its control over transboundary waters and potentially ‘choke’ the Indian economy. With the Brahmaputra megaproject, China has provided an answer.

The planned 60-gigawatts project, which will be integrated into China’s next Five-Year Plan starting in January, will reportedly dwarf China’s Three Gorges Dam—currently the world’s largest—on the Yangtze River, generating almost three times as much electricity. China will achieve this by harnessing the power of a 2,800-metre drop just before the river crosses into India.

What the chairman of China’s state-run Power Construction Corporation, Yan Zhiyong, calls a ‘historic opportunity’ for his country will be devastating for India. Just before crossing into India, the Brahmaputra curves sharply around the Himalayas, forming the world’s longest and steepest canyon—twice as deep as America’s Grand Canyon—and holding Asia’s largest untapped water resources.

Experience suggests that the proposed megaproject threatens those resources—and China’s downstream neighbours. China’s past upstream activities have triggered flash floods in the Indian states of Arunachal and Himachal. More recently, such activity turned the water in the once-pristine Siang—the Brahmaputra’s main artery—dirty and grey as it entered India.

About a dozen small or medium-sized Chinese dams are already operational in the Brahmaputra’s upper reaches. But the megaproject in the Brahmaputra Canyon region will enable the country to manipulate transboundary flows far more effectively. Such manipulation could leverage China’s claim to the adjacent Indian state of Arunachal, which is almost three times the size of Taiwan. Given that China and India are already locked in a tense, months-long military standoff, which began with Chinese territorial encroachments, the risks are acute.

And yet the country that will suffer the most as a result of China’s Brahmaputra dam project is not India at all; it is densely populated and China-friendly Bangladesh, for which the Brahmaputra is the single largest freshwater source. Intensifying pressure on its water supply will likely trigger an exodus of refugees to India, already home to millions of illegally settled Bangladeshis.

The Brahmaputra megaproject also amounts to a slap in the face of Tibet, which is among the world’s most biodiverse regions and has a deeply rooted culture of reverence for nature. In fact, the canyon region is sacred territory for Tibetans: its major mountains, cliffs and caves represent the body of their guardian deity, the goddess Dorje Pagmo, and the Brahmaputra represents her spine.

If none of this deters China, the damage it is doing to its own people and prospects should. China’s over-damming of internal rivers has severely harmed ecosystems, including by causing river fragmentation and disrupting the annual flooding cycle, which helps to refertilise farmland naturally by spreading silt. In August, some 400 million Chinese were put at risk after record flooding endangered the Three Gorges Dam. If the Brahmaputra mega-dam collapses—hardly implausible, given that it will be built in a seismically active area—millions downstream could die.

The Great Himalayan Watershed is home to thousands of glaciers and the source of Asia’s greatest river systems, which are the lifeblood of nearly half the global population. If glacial attrition is allowed to continue—let alone to be accelerated by China’s environmentally catastrophic activities—China will not be spared.

For its own sake—and the sake of Asia as a whole—China must accept institutionalised cooperation on transnational riparian flows, including measures to protect ecologically fragile zones and agreement not to dam relatively free-flowing rivers (which play a critical role in moderating the effects of climate change). This would require China to rein in its dam frenzy, be transparent about its projects, accept multilateral dispute-settlement mechanisms and negotiate water-sharing treaties with neighbours.

Unfortunately, there is little reason to believe this will happen. On the contrary, as long as the Chinese Communist Party remains in power, the country will most likely continue to wage stealthy water wars that no one can win.

If the tradition still holds, arriving on Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s desk this week will be a report setting out the Australian intelligence community’s best guesses (they will call them ‘judgements’) as to big strategic developments that could go horribly wrong in 2021.

We will probably never see that report, so in its place here are my best judgements (you can call them ‘guesses’) as to the likely prospects for peace, conflict and the in-between stage now called the ‘grey zone’, where aggressors advance their interests covertly.

Here are a couple of take-to-the-bank strategic certainties for 2021. First, there will be no repair or reset to our China relationship because the Chinese Communist Party under Xi Jinping thinks it’s essential to ‘punish’ Australia so that other democracies don’t get the uppity idea that the party will treat them respectfully as equals.

Beijing is probably just beginning to work through the list of Australian exports to be banned or punished with tariffs. Don’t be surprised if the CCP starts to limit tourist and student visas ahead of any real resumption of travel.

Aggressive and insulting propaganda will ramp up, the worst of it directed to Mandarin speakers. How ugly can it get? Pre-Covid-19 there were more than 10,000 Australian citizens in mainland China and around 100,000 in Hong Kong. The number now will still be substantial. In July, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s Smartraveller website advised that Chinese ‘authorities have detained foreigners because they’re “endangering national security”. Australians may also be at risk of arbitrary detention.’

We don’t know how far Xi will take his use of the ideology of ‘struggle’ to mobilise aggressive nationalism, but this is now a central element of his rule. Australians in China need to be conscious of the personal risk this creates.

The irony is that China is helping Australia achieve the substantial delinking from the Chinese economy which our sovereign interests and self-respect needs. Thanks, wolf warriors!

Another certainty is that Australia will continue to be under full-on cyber assault, principally from China, but it’s also likely that the Russian Intelligence hack into America’s government, security and business networks via the Texas company SolarWinds will impact Australia.

The attack using a SolarWinds ‘Orion network monitoring product’ is so serious that the White House’s National Security Council met to discuss it last weekend. Notwithstanding President Donald Trump’s undisciplined tweet suggesting that China rather than Russia was the culprit, it seems most likely that Russian intelligence installed malign code into a legitimate SolarWinds update from March, which SolarWinds sent to 18,000 customers to install.

This software allowed attackers remote access to the unclassified databases of the Pentagon, the US military, intelligence agencies and the organisations managing America’s nuclear arsenal.

Should Australia be worried? A review of the government’s AusTender contract database reveals that many federal departments and agencies are recent customers of SolarWinds, including Defence’s Chief Information Officer Group, the equipment-purchasing Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group, and the Defence Science and Technology Group.

Other recent Australian customers include the cyber intelligence agency the Australian Signals Directorate; the Department of Home Affairs; Austrade; the Department of Education, Skills and Employment; the Department of Finance; the Bureau of Meteorology; and the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency.

My understanding is that SolarWinds’ compromised Orion product accounts for about half the company’s business. Maybe there’s no problem in Australia—or we’re just yet to hear of a major security compromise. The government’s Australian Cyber Security Centre recommends ‘disabling internet access to Orion servers’.

The wider point is that Australia is under constant, sustained cyberattack from sophisticated and persistent state actors that have shown a determination to get into our networks, ranging from parliament to security and intelligence agencies, universities and businesses.

Does the Morrison government have the right level of attention on cybersecurity? We have yet to hear a minister comment on the SolarWinds attack from an Australian perspective. At the recent ministerial reshuffle, the word ‘cyber’ has disappeared from the title of any minister in Morrison’s second ministry.

It’s true that Foreign Minister Marise Payne has a strong interest in international cyber diplomacy and that Peter Dutton’s Department of Home Affairs released a cyber strategy last August, but cybersecurity is central to supply-chain security and the risk to our critical infrastructure is growing.

What is the risk of military conflict in 2021? Australia’s defence strategic update released in July says that ‘the prospect of high-intensity conflict in the Indo-Pacific, while still unlikely, is less remote than in the past’. In my view this understates the risk.

All through 2020 we have seen China’s military engaged in high-risk exercises and air- and sea-space incursions against neighbours in the South and East China seas and around Taiwan. A bloody hand-to-hand fight along the line of control in the Himalayas saw India and China engaged in direct combat.

Xi’s wolf-warrior nationalism is clearly clouding China’s normally cautious military judgement. Around China’s borders, this burst of nationalist overconfidence could give rise to a military confrontation that starts, perhaps, as the mistaken sinking of a ship or shooting down of an aircraft and then escalates until political intervention pauses military action.

Beijing clearly thinks that it has a window of opportunity to advance its military control around the so-called first island chain from Japan through to Taiwan and the Philippines. With America going through an ugly presidential transition and wracked by Covid-19, Xi may think this is the moment to apply maximum pressure on Taiwan to accept Beijing’s political control.

Would a newly sworn in US President Joe Biden intervene to defend Taiwan? If he failed to do so, that would end America’s Pacific alliances. More likely, Washington would provide military support and expect Japan and Australia to be involved.

What Australia should do in the event of a conflict or a military stand-off over Taiwan is one of these awkward discussions Canberra prefers not to have. But there is no exit strategy from our own region.

Finally, North Korea. Expect Pyongyang to test Biden’s resolve early, either by a nuclear test, possibly atmospheric, or with an intercontinental ballistic missile launch. Over three generations, the Kim regime has sought to push the US into making concessions, offering assistance or at least reducing sanctions in return for nuclear negotiations.

Biden must confront the horrible reality that North Korea now has close to a reliable capacity to hit an American city with a nuclear warhead. Trump’s failed attempt to negotiate directly with Kim Jong-un leaves Biden with deadly unfinished business.

The signing of a $204 million memorandum of understanding between a Chinese government-backed fishery company and the Papua New Guinea government to build a ‘comprehensive multi-functional fishery industrial park’ on the Torres Strait island of Daru has triggered starkly different responses in PNG and in Australia.

Daru is the administrative hub for PNG’s impoverished and underdeveloped Western Province (also known unofficially as Fly River Province). It’s one of the few islands in the Torres Strait that’s not Australian territory, and it’s only a short dinghy ride from the Australian border.

Since I wrote about the MoU in the regional Far North Queensland newspaper Cape and Torres News on 19 and 26 November, and then in The Guardian on 27 November, Jeffery Wall’s 8 December follow-up story in The Strategist triggered multiple reports, all echoing concerns about regional security, depletion of the fishery and a worsening of trade relations with China.

Canberra’s subsequent chest-thumping about Beijing’s ‘big, bad wolf-warrior’ diplomatic tack no doubt had Xi Jinping chuckling.

China’s ambassador to PNG, Xue Bing, said on 12 November that the Daru project ‘will definitely enhance PNG’s ability to comprehensively develop and utilise its own fishery resources’. PNG Fisheries Minister Lino Tom said it was a ‘priority project’.

While China’s record of unsustainable fishing practices is worrying, it’s important to note that this deal is with a PNG government in disarray. It’s only an MoU, many of which fail to evolve into anything concrete, such as the 2016 $5 billion agreement to construct two industrial parks in West Sepik Province.

The Australian National University’s Graeme Smith told the South China Morning Post: ‘An MoU signing ceremony in Papua New Guinea means almost nothing; they’re a dime a dozen.’

I discussed the implications of this deal with traditional inhabitant members of the Torres Strait fishery on the Australian side of the border. They are already suffering from the live-seafood export ban imposed by their biggest customer, China, and are concerned about the proposed development’s impact on their industry, but they are pragmatic about it.

Torres Strait Islanders have long aspired for regional autonomy and more economic independence, and managing their fishery industry is seen as the best way to do that.

Torres Strait community fisheries representative Kenny Bedford told me this week: ‘News of this MoU was always going to ring alarm bells for us.’

But he said another perspective now emerging is the trade opportunity this sort of infrastructure development could represent for the region. It is timely given that a local company, Zenadth Kes Fisheries, has just been established.

‘Finding ways to add value and better market our produce are key objectives of the new entity. This regional development could result in direct trade with China through a much closer port facility’, Bedford said.

Edmund Tamwoy, a Torres Strait fisher from the island of Badu agreed.

‘With all the chaos that’s going on, we might as well deal directly with Daru and I’m open to discussion with the Chinese. If it’s going forward then it’s about us being smarter and seeing how we can tap into it.’

The Australian quoted Foreign Affairs Minister Marise Payne as saying that commercial-scale fisheries would not be considered a traditional activity under the Torres Strait Treaty and would not be permitted. ‘Only residents of the protected zone are able to undertake such activities’, she said.

That is not correct.

Australia and PNG are allowed to fish commercially in the shared area of the waters known as the protected zone, which straddles the fishing zones of the two countries.

As the Australian Fisheries Management Authority website states, inside Australia’s zone, PNG boats may take 25% of the permitted tropical lobster catch and 40% of Spanish mackerel.

To date, PNG has not had the capacity to commercially fish its share of these quotas, but the deal could attract Chinese funding for PNG-flagged vessels that could fish within a couple of kilometres north of Thursday Island. That would be completely legitimate commercial activity that Australia would have no legal right to prevent.

Sources in the Torres Strait tell me there has been no application, yet, for PNG to access its share of the fishery.

When I questioned federal MP for Far North Queensland Warren Entsch, the Australian Fisheries Management Authority, the Australian Border Force, and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade about the MoU last month, I got the sense that they had either not been aware of it or not considered its implications.

It took over a week for the government departments to provide me with their similar and carefully crafted responses that all echoed the DFAT line of, ‘We expect all fishers in the Torres Strait region to follow respective Australian and Papua New Guinean laws and international obligations.’

However, a week after the MoU signing, the ABF announced that it had covertly deployed five hydrophones on the ocean floor, ‘across the Torres Strait to combat illegal activity in the region, particularly illegal foreign fishing’.

These underwater microphones are new technology developed with CSIRO that can in real time ‘listen to vessel traffic and behaviour to assist in detecting activity such as illegal fishing and the movements of vessels involved in other illicit activities’, the ABF statement said.

However, all of the commentary to date has avoided the elephant in the room—that there’s been a presumption PNG will remain an underdeveloped backwater indefinitely.

Anyone, including Australian commercial interests, could have cut the same deal with Daru, but in the last four decades of this fledging nation’s history nobody has done that. Now we want to cry wolf-warrior diplomacy at both our neighbour’s aspirations of prosperity and our biggest trading partner’s willingness to facilitate it?

Might Australia have been asleep at the helm in the Torres Strait?

In this edition, we take a look at how the Chinese military is preparing for the future land combat environment.

Unlike China’s relatively cogent thinking on future warfare in the air, maritime, cyber and space domains, its thinking on land combat has been increasingly incoherent. Indeed, the strategic priorities the Chinese Communist Party has been setting for the military since the 1980s have required a shift in emphasis from land power to air and sea power. With the Soviet Union gone and China’s land borders largely settled (disputes with India notwithstanding), the People’s Liberation Army Ground Force (PLAGF) has struggled to find a meaningful purpose in China’s future force structure beyond sustaining the capability needed to win a limited war on the Sino-Indian border.

Some of the incoherence is best laid out by military commentators within China itself. In an article in the People’s Liberation Army Daily, Wang Ronghui seeks to explore the role armoured forces will have in future warfare. Writing with much jargon and little detail, Wang argues that the recent history of armed conflict has confirmed the armoured forces’ role as the ‘king of land warfare’ (陆战之王).

Armoured forces, Wang observes, have proved adept at ‘incorporating highly advanced weapons technology’. Equipment such as armoured fighting vehicles and main battle tanks have become sufficiently flexible and adaptable to changes on an information-dense battlefield. Without providing much evidence, Wang argues that these characteristics of armoured warfare have effectively disproved the ‘useless tank theory’ (坦克无用论).

After beginning the essay with vague statements about the nature of land warfare, Wang moves on to provide a strategic rationale for why the PLAGF needs a strong armoured force. ‘Armoured forces have important missions in resolving territorial disputes, resisting foreign invasion, stabilising borders and safeguarding territory along with other warfighting roles’, he says.

There are significant issues with this line of argument. Not only have China’s land borders largely been settled, but, on the one land border that China hasn’t settled, namely with India in the Himalayan mountains, armoured forces would find it extremely hard to operate as the terrain is extremely rugged. Absent a critical security threat, the main uses of armoured forces would be for stabilisation missions along the North Korean border, exercises in Central Asia with members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and, perhaps, in a land invasion of Russia or Mongolia. What this suggests is that China’s land warfare thinkers are struggling to find a sustainable role for armour in the PLA’s force structure.

With those thoughts in mind, what does the future hold for the PLA’s ground forces? Politically, the PLAGF has always been the dominant force in the Central Military Commission. Yet China’s 2015 defence white paper emphasised that the PLAGF needed greater mobility between theatres, and suggested an emphasis on small, multifunctional and modular units that would enable the PLAGF to adapt itself to tasks in different regions.

This emphasis on greater mobility and flexibility is influencing capability development and shaping the nature of military exercises, with a growing emphasis on combined arms mechanisation, and joint and integrated military operations. The 2019 defence white paper notes that the PLAGF ‘is speeding up the transition of its tasks from regional defense to trans-theater operations, and improving the capabilities for precise, multi-dimensional, trans-theater, multi-functional and sustained operations, so as to build a new type of strong and modernized land force.’

More recently, there have been indications that a goal in the 14th Five Year Plan (2021–2025) will be to accelerate military modernisation so that the PLA will be fully mechanised and informationised by 2027—the 100th anniversary of its founding. Chinese military expert Dean Cheng argues that that will require a major reduction in forces, a major budget increase or a redefining of what constitutes ‘informationised’ units.

The lingering effects of Covid-19 on the Chinese economy are likely to place pressure on the defence budget, forcing the PLA to focus more on developing a streamlined, ‘meaner but leaner’ military. With the PLA Navy, Air Force, Rocket Force and Strategic Support Force eating up most of the funding, it’s possible that the PLAGF will face further cuts.

The challenge for the PLAGF leadership is seeing this as an opportunity rather than a risk. Trimming the fat by scrapping outdated capabilities and reshaping army organisation to be better prepared for warfare in a variety of operational theatres would allow the PLAGF to play a more even role alongside air, naval, space and missile forces. That could mean lighter, more agile and mobile ground forces, integrated with army aviation and long-range fires, as well as a greater focus on embracing technology such as lethal autonomous weapons.

China’s military is facing the same challenges as most of the world’s armed forces—how to transform and adapt to new approaches to operations and new types of technology within constrained budgets. For the PLAGF leadership, that may mean having the courage to throw off old capabilities that were suited towards ‘people’s war under modern conditions’ in the 1980s and instead move decisively towards integrated joint operations as part of informationised and intelligentised warfare for the 21st century. It also means prioritising an ability to deploy rapidly across multiple theatres within China and to project force beyond China.

Given that the principal strategic direction for the PLA remains ‘reunification’ with Taiwan and, more broadly, China’s littoral in the western Pacific, the PLAGF must have the ability to be an expeditionary force. Getting bogged down with heavy armour may be the wrong move.

The requirement for nimble, expeditionary forces that can operate in an information-dense environment should shape the future capability development of the PLAGF in coming years. The question is whether it will.

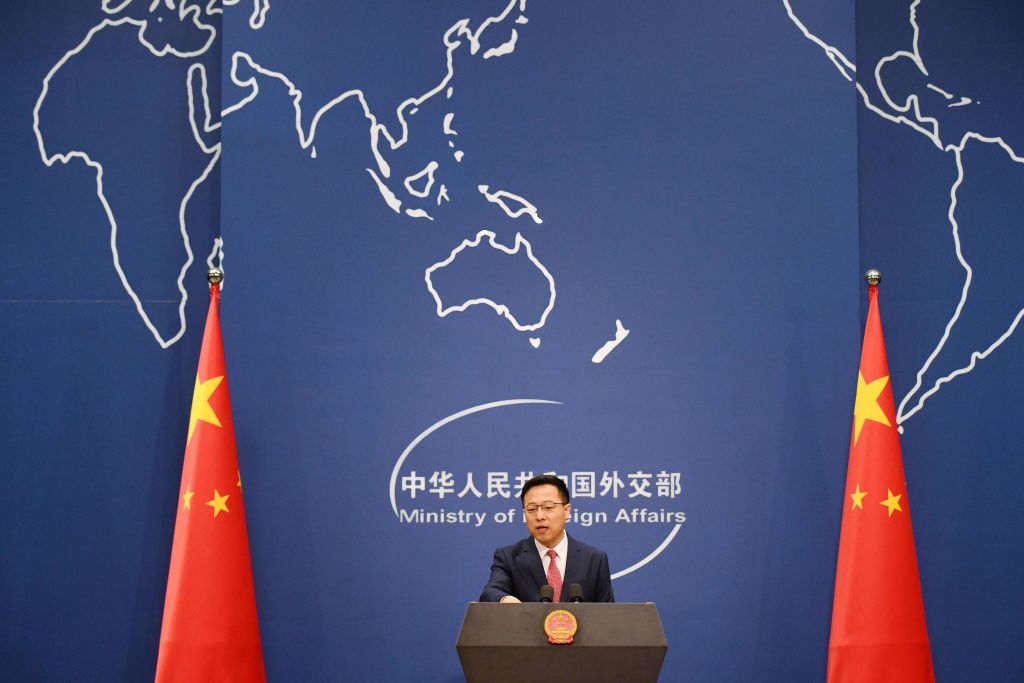

The contrast between Australia’s open system of government and China’s authoritarian system was put on graphic display yesterday through Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian, when he tweeted a fake image and criticised Australia for human rights abuses in Afghanistan—and not in any way that plays to Beijing’s advantage.

Zhao used a doctored photo of an Australian soldier to support a statement that Beijing was ‘shocked’ by the alleged unlawful killings of Afghans by Australian special forces personnel. And he then called on our government, which of course knows of the alleged abuses, to hold Australian officials (soldiers) to account.

The effect of Zhao’s intervention is likely to be something he and his audience in Beijing, the senior Chinese Communist Party leadership, could have predicted, but seem not to have: it will simply cause more governments, more civil-society organisations and more citizens in multiple countries to inquire into the mass-scale abuses that Beijing’s authorities are committing every day in Xinjiang and now in Hong Kong.

So, Zhao’s actions will only further harm China’s already collapsing soft power internationally and make others question the assumptions they have made about engaging economically and politically with the Chinese state. That’s all bad news for Beijing.

There’s some good news for Zhao, though. What he’s called for—accountability of Australian officials who have committed crimes or abuses—is exactly what the Australian government is already in the process of doing. Let’s remind ourselves why.

The world knows about the alleged unlawful killings of 39 Afghans because of a forensic inquiry conducted by Australian authorities, whose findings were publicly released.

In contrast, the world knows about the more than 1 million Uyghurs in detention camps in China only through first-hand accounts of escapees, leaked Chinese government documents, and analysis of satellite imagery.

The Australia government’s response to allegations of special forces misconduct was to initiate a comprehensive, four-and-a-half-year-long investigation, and to foreshadow criminal charges for Australian personnel.

Beijing’s response to allegations of mass-scale abuses of its Uyghur citizens has been denial and misrepresentation.

At first, Chinese government officials said there were no camps. When it became impossible to sustain that argument, they shifted to their current explanation that the mass detention camps are ‘vocational education’ centres. This is simply untrue.

Zhao is absolutely right in saying that governments must be accountable for abuses committed by their officials.

The key question he has not answered (and almost certainly won’t and can’t if he’s to survive in his role) is, when will Beijing take responsibility for its acts in Xinjiang and Hong Kong with a level of accountability approaching that Australia is taking for the abuses in Afghanistan?

It seems to make no sense for Beijing to call attention to its own appalling human rights behaviour, so why is its foreign ministry doing so?

The first reason is that this performance is not mainly for the international community; it’s another case of Chinese diplomats engaging in aggressive ‘wolf warrior’ diplomacy to demonstrate to Xi Jinping that they are doing what he wants—showing strength and engaging in China’s ‘struggle’ with the rest of the world. Zhao is performing for the members of the CCP’s politburo and probably for other senior party members in Beijing who control careers and success for people like him.

The second reason is based on a miscalculation: Beijing seems to assess that bullying and intimidating the Australian government and using trade as a weapon are the best ways to undo Australian decisions that go against Beijing’s interests.

It should be getting obvious to Beijing that this is an error, and that any further effort along these lines will only harden Australian public opinion and support the analysis that underpinned Australian decisions on foreign interference, foreign investment and digital technology. It will also make other governments and policymakers much more interested in Australia’s decision-making, as we have seen on 5G technology.

Maybe even more importantly, it will reinforce a growing move by Australian businesses to diversify away from all-in bets on the Chinese market, as we heard so clearly in the case of Treasury Wine Estates this week.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison was right in politely but clearly calling on the Chinese government to apologise for and remove Zhao’s tweet about the alleged unlawful killings by Australians in Afghanistan.

That won’t happen, but Morrison’s clear response will help others understand that the issues here are all in Beijing, not Canberra. He’s also telling Beijing that Australia has respect for itself and for the soldiers who fight in our name.

In the medium and long terms, as Australian businesses respond to the growing risk in the closing China market, and as Beijing’s bullying scores it more own goals internationally, Morrison’s stance will create what Beijing says it wants most: a foundation for a mutually respectful relationship.

Such a relationship will be possible only if, along with retaining our self-respect, we reduce the economic leverage Beijing has over us. Selling 20% of our annual lobster catch to Chinese consumers, instead of the 90% we do now, would be an example of that sensible future. Beijing is doing what it can to help this trade rebalance happen.

In this special episode, The Strategist’s Anastasia Kapetas speaks to some of the team behind ASPI’s research on Xinjiang about their recently launched Xinjiang Data Project and the potential global implications of China’s treatment of the Uyghurs in the region.

Kelsey Munro, Nathan Ruser and James Leibold discuss their research, which mapped out 380 detention facilities in Xinjiang that have been built or expanded on since 2017.

They also talk about their research on cultural erasure in Xinjiang which traced the destruction of mosques and other significant Uyghur cultural sites in the region and estimated that 16,000 mosques have been destroyed or damaged in the last three years.

Chinese President Xi Jinping recently told the People’s Liberation Army Marine Corps to ‘put mind and energy on preparing for war’ as the United States announced plans to sell three advanced weapon systems to Taiwan, an island China considers to be its ‘lost province’ following the Nationalists’ defeat in the Chinese civil war. In his speech, given in Guangdong Province only a few hundred kilometres from Taiwan, Xi emphasised that the Chinese marines are an ‘elite amphibious combat force’ responsible for ensuring ‘territorial integrity’. The message was clear: the PLA Marine Corps would be vital in an invasion of Taiwan.

China has dramatically upgraded its military arsenal in preparation for this and other maritime confrontations in the Indo-Pacific, alarming countries worldwide that have security and shipping interests in these waters. Beijing is showing with these actions that it is ready to challenge a rules-based world order and pressure nations that do not accede to its will. The global shocks caused by the Covid-19 pandemic have helped unmask the Chinese Communist Party’s ambitions to establish itself as a world power, but at the same time, the CCP also faces uncertainty over China’s chances of achieving Xi’s strategic targets to ‘comprehensively build a moderately prosperous society’ by 2021.

Wary of a new world order revolving around China’s authoritarian regime, the US, Japan, Australia and India have reactivated the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue after more than a decade of somnolence. The Quad is an informal grouping that involves summits and information exchanges and this year will include combined military drills known as the Malabar exercises. By inviting Australia to participate in the Malabar drills, New Delhi has upgraded its security relationship with Canberra, even though building such alliances antagonises Beijing.

The promise of ‘win–win’ solutions for all who participate in China’s peaceful pursuit of prosperity has been replaced by an extensive military build-up, growing control of global shipping lanes, and efforts to secure Chinese naval access in contested maritime regions. China has also been putting economic pressure on a number of nations, some of which have responded by banding together to stand up to its attempts at coercion.

The improving ratio of Chinese versus American warships, missile arsenals, nuclear reach and technological capability sees China emboldened and ready to further assert its will over global affairs. The recent sabre-rattling over Taiwan is just another indication. China dangles the promise of access to the vast riches of its markets, but penalises nations that criticise it by imposing punishments including ultra-high tariffs, denial of market access, predatory economics and even imprisonment of foreign citizens, among other coercive tactics.

Against this ominous backdrop, the Quad presents itself as having a positive agenda—a diplomatic network that assists democracies, as Australian Foreign Minister Payne puts it, ‘to align ourselves in support of shared interests … governed by rules, not power’.

The Quad formed in 2006 as a discussion forum on the rise of China and India and maritime issues in the Indo-Pacific. It met once in 2007, but the informal alliance became dormant due to Australia’s and India’s reluctance to undermine what had been healthy bilateral relations with China. Beijing’s moves since 2012, however, have altered the calculus in how much and how far to challenge China.

The US, Japan, Australia and India now share the common challenge of deteriorating relations with China. India faces border clashes in the Himalayas; Australia experiences economic and political coercive pressure; Tokyo is in dispute with Beijing over Chinese vessels patrolling near the Japanese-controlled Senkaku Islands, which China claims. Australia, Japan and the US have also spoken out against China’s crackdown on the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong, mass detention of ethnic Uyghurs in Xinjiang, and contested claims in the South China Sea. These nations’ relations with China are at rock bottom. But they can sink further; China has already denounced the Quad as an ‘elite clique’ attempting to contain its rise.

That China finds the Quad as such a challenge reveals a fragility to its ascendancy as it seeks to alter the world order to reflect its interests. For its part, the US has embraced the Quad as a way to maintain a free and open Indo-Pacific and to promote and retain a liberal world order, policy goals articulated in its 2017 national security statement. In addition to these goals, Japan, Australia and India seek a balancing of approaches to China’s coercive policies in the region.

As China rapidly rewrites international rules to better reflect its desires, it’s hardly surprising that others are responding by protecting their own interests. Already, geostrategic and military alliances beyond the Quad are being worked out. Looking ahead, a space alliance between Quad members may also become feasible. The ‘Quad-Plus’—the four Quad nations and Vietnam, South Korea and New Zealand—has already met to discuss coordinated responses to the pandemic.

Quad members and others must now confront a key decision: whether to have difficult conversations about and with China, or hope that win–win outcomes can still be achieved by effective diplomacy and mutually beneficial trade relations. At this stage it is apparent that the latter strategy has been ineffective and that stronger combined measures are required.