Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

The Australian and United States governments both ordered urgent reviews of their supply chains last week amid growing concern about their vulnerability to disruption by China.

Australia’s Productivity Commission, which typically takes three or four months to prepare an interim report and a year or more to complete a study, has been given just one month to deliver its initial findings on the nation’s dependence on imports. A final report also looking at risks to exports is to be handed to the government by the end of May.

The final report will identify supply chains ‘vulnerable to the risk of disruption and also critical to the functioning of the economy, national security and Australians’ well being,’ as well as proposing risk-mitigation strategies.

The parallel investigation in the US is initially examining supply-chain risks in four key industries—computer chips in consumer products, large-capacity batteries, pharmaceuticals and critical minerals—with all relevant federal agencies required to report on risks within 100 days. This will be followed by a broader year-long review.

US President Joe Biden announced the review saying, ‘Remember that old proverb, for want of a nail, the shoe was lost? For want of a shoe, the horse was lost. And it goes on and on and on until the kingdom was lost, all for the want of a horseshoe nail. Even small failures at one point in the supply chain can cause outsized impacts further up the chain.’

Although neither the Australian nor the US government referred explicitly to China, Biden made it clear who the initiative was aimed at.

‘We shouldn’t have to rely on a foreign country—especially one that doesn’t share our interests, our values—in order to protect and provide [for] our people during a national emergency,’ he said.

The Productivity Commission has asked for submissions on how firms manage and respond to disruptions in export market access and the impact that these disruptions can have, including in regional areas, a clear reference to the barriers China has erected to Australian exports.

Supply-chain vulnerability has been on the radar of governments around the world since shipments of personal protective equipment were hit by export restrictions following the outbreak of Covid-19. There is a renewed focus on manufacturing self-sufficiency in many nations. Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s government has promised $1.5 billion in ‘co-investment’ to assist firms to boost the scale of their domestic operations.

Australia’s growing trade friction with China is adding urgency to the issue. Any attempt by China to reclaim Taiwan could result in trade embargoes with massive repercussions for the global economy. It’s a development that has been widely canvassed by strategic analysts, including ASPI Executive Director Peter Jennings, and is doubtless being assessed by national security authorities. China accounts for around 15% of world trade.

A study by a UK think tank, the Henry Jackson Society, last year examined the dependency of the Five Eyes countries—the US, the UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand—on China and found that Australia was by far the most exposed.

Although China’s outsized share of Australia’s exports is well understood, its dominance of imports is less widely appreciated. The study used United Nations data, which divides global trade into 99 industries, with each industry having 99 sectors and each sector 99 categories of goods.

The study applied three tests to establish whether a country was strategically dependent on China: the country had to be a net importer of the goods in question, more than half its imports of the goods had to come from China, and China’s global market share of those goods had to be greater than 30%. The tests meant that in the event that supplies from China were interrupted, it would be difficult for the importing nation to replace them.

It found that of the 5,914 categories of goods imported by the five nations, Australia was strategically dependent on China for 595, which was more than any other country.

Five Eyes’ strategic dependence on China

|

Australia |

Canada |

New Zealand |

United Kingdom |

United States |

|

| Industries |

14 |

5 |

10 |

4 |

6 |

| Sectors |

141 |

87 |

125 |

56 |

102 |

| Categories |

595 |

367 |

513 |

229 |

414 |

Source: Henry Jackson Society. In the case of the US, the UK, New Zealand and Canada, the most recent data available was from 2019. In the case of Australia, the most recent data available was from 2018.

Each of the five nations has identified critical industries, including communications, energy, health, transport, water, finance, critical manufacturing, emergency services, food and agriculture, information technology and government facilities.

Australia was dependent on China for more than half the supplies to three industries, 37 sectors and 167 categories. This was by far the greatest level of dependency among the five nations.

A separate analysis of the UN data by this correspondent shows that China has a massive market share for crucial inputs to many industries in Australia. For example, it provides 86% of all Australian semi-conductor imports, 75% of lighting, 72% of generators and 68% of computers.

Broad product categories conceal points of extreme dependence. China supplies 40% of Australia’s imports of nuts and bolts, but that share will be closer to 100% for some specifications. The same is true of Chinese supplies of essentially humble but indispensable products like hinges, padlocks and gaskets.

The UN data shows Australia is 100% dependent on China for supplies of manganese, crucial for stainless steel and other alloys, and more than 90% dependent for fertilisers. Although porcelain toilets and basins might not be seen as a critical input, 82% come from China and the residential construction industry would be brought to a halt without them.

The Productivity Commission will find that the spread of goods on which Australia is dependent on China is so broad that it’s impossible to conceive of any realistic replacement or supply-line duplication strategy.

The best articulated strategy for dealing with interruptions to Australia’s supplies is the 1984 National Liquid Fuel Emergency Response Plan, which provides for fuel rationing with specified exemptions for essential services. Dealing with the wholesale interruption of supplies from China would likely require the invocation of national emergency powers beyond those included in newly updated legislation which was primarily designed to deal with natural disasters.

This week, an editorial in the Chinese state-run newspaper the Global Times alleged that the almost 80-year-old Five Eyes alliance of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States is an ‘axis of white supremacy’. Such blatantly ridiculous statements beggar belief and most certainly do not warrant a response. More interestingly, though, the editorial is symptomatic of four critical flaws in the Chinese Communist Party’s strategic thinking about China’s future.

The first is a fundamental confusion over hegemony. When discussing the Five Eyes, the Global Times argues, ‘We cannot allow their selfishness to masquerade as the common morality of the world, and they cannot set the agenda of mankind.’

That kind of thinking conflates dominance and leadership. While it is, of course, possible to be dominant, real power comes from leadership.

Domestically, the CCP prefers to exercise its power to assert constrictive control over its population. Exercising this kind of absolute control or power in international relations is neither possible nor desirable.

The global powerhouses in international relations are reliant not on coercion, threats or control but on leadership and influence. Attempts to challenge the rules-based order with soft power or coercive and divisive threats will not result in CCP hegemony and are not a zero-sum game. When it operates within the rules-based order, the CCP’s penchant for division and dominance does little for maintaining peace, security and economic prosperity.

Second, international relations is not an activity that lends itself to binary choices or generalisations. There’s a strange irony to the Global Times’ invoking of concepts of ‘Anglo-Saxon civilization’. Like the CCP’s broader strategic thinking, this perspective has more in common with dated biblical questions like, ‘Are you for us or for our enemies?’—an attitude largely abandoned in Western culture, let alone international relations. Let’s not forget that US President George W. Bush tried a similar turn of phrase in 2001, and it fell flat.

Engagement in the rules-based order is not concerned with a series of simplistic black-and-white questions or a matrix consisting of shades of grey; it is a rich and complex endeavour more akin to a Jackson Pollock painting than a Mark Rothko. As argued by Czeslaw Milosz, ‘The true enemy of man [humanity] is generalisation.’

Third, thinly veiled threats and coercive actions, economic or otherwise, are having less and less success. China’s constriction of rare-earth supplies to Japan, and later the US, has led them to initiate all-new strategies to secure their supply chains. More than a year of the CCP’s economic sanctions against Australia has hardened Canberra’s resolve and tarnished Beijing’s global reputation.

Finally, and most importantly, divisive wedge strategies and identity politics, whether at the national, bilateral or regional level, do not create power.

While the CCP’s identity politics may have some traction domestically, it falls flat internationally. Stoking the fires of identity politics is by its very nature harmful. Narrative gestures that seek to link the governments of the Five Eyes countries with the increased ‘transnational threat’ of white-supremacist movements and pit their ‘tiny’ populations against the rest of the world along this fictional battleline are a homogenising tool that is counterproductive to the international diversity the CCP claims to champion.

In 2018, Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews’s memorandum of understanding with the CCP to be part of the Belt and Road Initiative surprised Canberra. Australia’s federation makes foreign affairs a matter for the Commonwealth government. The BRI agreement is an egregiously manipulative CCP endeavour likely designed to force a divisive wedge between the Commonwealth and the states. But the federation is strong enough to survive this.

Perhaps fear of Chinese economic retribution was behind recent ministerial suggestion from New Zealand that Australia should ‘show respect’ to China. Little wonder that this latest Global Times editorial tries to drive a wedge between the Five Eyes members. Australia and New Zealand have strong cultural and historical roots. And small New Zealand has expended blood and treasure for its allies.

The CCP is anxious about effective multilateralism, as its advantages come from dealing bilaterally. It’s much easier to exert control when you’re the much bigger party in a two-way relationship.

The Chinese state uses a divisive approach to multilateralism. Even the most casual observer can see this strategy playing out in the way the it engages with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and its member states.

For decades, the economic development of ASEAN members was hindered by persistent shortages in high-quality infrastructure. The issue wasn’t a lack of desire but a lack of access to equity and investment.

Chinese direct investment was already flowing into the region before President Xi Jinping announced the BRI in 2013. Nonetheless, the introduction of the program was a watershed moment in ASEAN infrastructure development. It has also made most ASEAN members increasingly economically reliant on China.

This investment, especially in Laos and Cambodia, has influenced not only these countries but also ASEAN’s collective responses. Intense reactions to the CCP’s actions in the South China Sea seem unlikely to be forthcoming.

There is, however, an awakening across the region to the dependency that Chinese investment brings. This realisation is driving all new connections within and with the region. Symbolic projects like the Australia–Vietnam friendship bridge in Dong Thap Province and the Vietnam–Japan friendship bridge in Hanoi show that there are alternatives.

The Global Times’ comical analysis is reminiscent of the 1950’s propaganda produced by the Soviet Union. The editorial also illustrates that one of the essential strategies for responding to the CCP’s attacks on multilateralism is a continued commitment to a rules-based order and the myriad possibilities it holds.

Following the changing of the guard in the White House, a re-energised Quadrilateral Security Dialogue linking the US, Japan, India and Australia needs to prepare itself to face serious global tensions in this year and beyond.

The Quad will have to deal with the erosion of liberal democratic values under pressure from authoritarian priorities as an ascendant China, supported by Russia, seeks to alter the fabric of the established world. Multilateral institutions such as the World Health Organization, United Nations and World Trade Organization now find themselves as ‘contested space’.

Washington’s increased support for the Quad includes a major US reorientation within the Indo-Pacific. President Joe Biden has already confirmed the region’s importance by appointing Kurt Campbell as Indo-Pacific coordinator to manage the US–China relationship. Campbell has endorsed some policies towards China initiated by Donald Trump’s administration, but he has also acknowledged that the US has much work to do in engaging with the region as a whole and in re-engaging with allies.

Another key element of the Biden administration’s strategy will be making greater use of assets such as satellites in developing national security policy and assessing foreign capabilities, including in space. China, and to a lesser extent Russia, are challenging America’s dominance in space, raising cybersecurity and infrastructure concerns in the US and the wider Indo-Pacific region.

The Quad will need to be involved in developing a cybersecurity strategy that recognises the varied nature of evolving threats and the importance of ensuring the security and resilience of alliance members’ networks. Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade is seeking to secure the technological future by fostering the ‘Quad Tech Network’.

This initiative opens a new ‘track 2’ Quad stream for universities and think tanks to promote research on and discussion of cyberspace and critical technology. Participants include the National Security College at the Australian National University, India’s Observer Research Foundation, Japan’s National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies and the US Center for a New American Security. DFAT’s focus is on addressing key technology- and cyber-related issues facing the region and fostering policy collaboration among Quad members. This focus will complement the department’s forthcoming international engagement strategy for cyber and critical technology, which is expected to focus on protecting critical infrastructure and assets while securing vital supply lines for technology development.

Competing visions for technological sovereignty and governance already disrupt geopolitics. A liberal perspective seeks a system that’s distributed mainly from the bottom up, with a vital non-government and private-sector role. In this model, international organisations promote level playing fields for trade, set standards and regulate fair economic competition.

China and Russia reject this model as broken and seek to reshape multilateral organisations to reflect their own interests. They favour an authoritarian model that mandates a state-centric, top-down approach to governance, altering institutions to better support and acknowledge the legitimacy of authoritarian practices. Beijing’s attempts to make the UN a platform that will ‘legitimise its authoritarian rule’, is an example of what China has in mind.

In the state-centric authoritarian model, global internet and cyberspace governance, including the management of information flows, becomes ever more important. China’s and Russia’s disinformation strategies have gathered traction in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. Beijing has taken advantage of disjointed Western responses and a dearth of cooperation and leadership among the democracies to alter views on the pandemic’s origin to better fit the Chinese Communist Party’s needs for legitimisation and international respect.

The ‘China Standards 2035’ plan lays out a blueprint for the CCP and leading state-owned technology companies to set global standards for emerging technologies like 5G, the internet of things and artificial intelligence, among other areas. This is intended to work in concert with China’s other industrial policies, such as the ‘Made in China 2025’ strategy, to make China a global leader in high-tech innovation, and dovetails into the Belt and Road infrastructure expansion.

As Beijing seeks to export its norms, values and governance practices to the rest of the world, concerted and urgent action by the Quad, and associates including NATO, is necessary to protect shared democratic values and the rule of law. NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said in his first policy speech since the US election that his organisation should ‘reach out to potential new partners in the community of democracies … and embrace a global outlook’.

Some argue that the Quad won’t work because the histories and agendas of the four partners are too different. However, this views the Quad narrowly as a military alliance. It can be and is much more. In an encouraging sign, the Quad has already engaged with South Korea, Vietnam and New Zealand (the ‘Quad-plus’) on collective responses to the pandemic.

As Quad members, the US and Australia may encourage the inclusion of Japan in the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing network along with Canada, New Zealand and the UK. The British government has also floated the idea of a ‘Democracy 10’ (including the Quad countries) to tackle issues, such as the development of standards for 5G and emerging technologies, that affect the collective interests of the democratic nations.

A key to the Quad’s future is its embrace of a multilateral and nuanced approach that builds on strategic alliances and partnerships globally. This is a strategic advantage that illiberal states cannot yet, and may never, match. However, as democracies rally, others will seek out new alliances. Keeping a step ahead won’t be easy.

US President Joe Biden has just signed an executive order launching a comprehensive review of America’s critical supply chains for strategically significant products and resources.

Among those are rare-earth elements, supplies of which the Biden administration says must not be ‘dependent upon foreign sources or single points of failure in times of national emergency’. ‘Foreign sources’ points a clear finger at one country which has dominated the market for decades.

China has used its near-monopolistic control of the global supply chain for rare-earth elements to strategic advantage against both the United States and Japan. The two countries have attempted to break China’s grip on rare-earth production over recent years using new green techniques.

As part of this effort, the US will reportedly accelerate efforts to work with Australia, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan to develop more resilient supply chains for semiconductor chips, electric vehicle batteries and other strategically significant products. However, there’s room for more strategic responses involving cooperation among Japan, the US and Australia to assure the mining and processing of the rare earths that are used to manufacture these products.

Rare earths are a group of 17 metals—15 elements from the lanthanide series and two chemically similar elements, scandium and yttrium. Each has unique properties that are vital for a range of commercial and defence technologies, including batteries, high-powered magnets and electronic equipment. An iPhone, for example, contains eight different rare-earth minerals, and there are probably a couple in your refrigerator and washing machine. They also make up about 420 kilograms of an F-35 fighter jet and are essential for guided cruise missiles.

Despite their name, rare earths are not all that rare. They’re present in abundance in the earth’s crust. The challenge, however, is finding them in sufficient concentrations to justify commercial mining operations. Securing the upfront financing required to build a mine in a location that will tolerate the substantial environmental impacts of establishing a rare-earth processing facility is no easy task.

Fortunately for China, the commercial viability of its reserves, Chinese companies’ access to state-backed financing and the country’s lax environmental regulations have helped build its dominance of the global rare-earth market.

According to the US Geological Survey, China accounted for at least 58% of global production of rare earths last year, and possibly up to 80% if you include illegal and undocumented production activity. China’s rare-earth production exceeds that of the world’s second-largest producer, the US, by more than 100,000 tonnes, and even then the US still relies on China for most of its rare-earth imports.

The Chinese state has realised that its control of the global market makes for a useful economic lever. In 2010, it effectively restricted rare-earth exports to Japan when a Chinese fishing trawler collided with a Japanese coastguard vessel near the disputed Senkaku Islands. More recently, it threatened to limit rare-earth supplies to US defence contractors, including Lockheed Martin, over its involvement with US arms sales to Taiwan.

China routinely adjusts its domestic production quotas and subsidises rare-earth prices to strategically flood the market when it wants to drive out competitors and deter new market entrants.

The US, in turn, has realised the need to develop a secure supply of rare-earths and has looked to Australia to help make that happen.

Australia has the world’s sixth-largest reserves of rare-earth minerals, though they remain largely untapped with only two mines producing them. The largest by far is the mine at Mt Weld in Western Australia, which is owned by Australia-based Lynas Corporation.

On 1 February, the Pentagon announced that it had awarded Lynas a second contract to develop a rare-earth processing facility in Texas.

The contract signed between Lynas and the US Department of Defence adds separation capacity for light rare-earth minerals to its planned heavy minerals processing facility in Hondo, Texas, announced last year. When the project is complete, Lynas—which is already the second-largest producer of separated rare earths globally—will operate two of the largest rare-earth processing plants outside of China. Not only is this a massive boon to Australia’s rare-earth industry, but it also gives the US substantially more access to rare earths in a global market that Beijing has long controlled.

While Lynas’s deal with the Pentagon is welcome news, the only new infrastructure being built under this agreement is in the US.

Compounding this challenge to China’s rare-earth monopoly has been the coup in Myanmar. China is dependent on rare-earth imports from Myanmar, particularly heavy rare earths. Imports of heavy minerals from Myanmar account for 60% of domestic Chinese consumption—and China is no stranger to restrictions imposed by the Myanmar government.

A long-term suspension of Myanmar’s rare-earth exports would be a shock to China’s supply chain. Filling the gap would require a sizeable boost to domestic production or additional foreign investment in an alternative supplier.

Days after the Pentagon announced its second contract with Lynas, Shanghai-based rare-earth processor Shenghe Resources signed a memorandum of understanding with West Australian mining company RareX Limited. If the deal goes ahead, Shenghe will hold a majority share of a new jointly owned rare-earth trading company that would likely source ore from RareX’s Cummins Range rare-earth mining project in northern Western Australia to be processed at Shenghe’s refineries in China.

The Cummins Range project will be a landmark project for northern Australia, bringing with it jobs and investment. The mine will likely transport rare-earth ores to either Wyndham or Darwin port to be shipped overseas for processing.

A Chinese state-owned company potentially investing in a new rare-earth mine in northern Australia should raise eyebrows in Canberra, Washington and Tokyo. The irony of descriptions of the project as a ‘great leap forward’ and RareX as ‘delighted to be moving towards securing an alliance’ ought not be lost on policymakers. There’s clearly a disconnect with Australia’s strategic policy settings when its partners have worked so hard to break China’s monopoly only to have the absence of equity investment push other Australian miners towards a Shanghai-listed company.

Australia’s critical minerals strategy of 2019 is largely focused on attracting foreign investment into new mining infrastructure. The renewed focus on the strategic and commercial importance of rare earths should be a stark reminder that, as the Northern Territory government’s Luke Bowen has written in The Strategist, Australia needs to back itself on rare earths instead of letting great-power competition lead the way.

While Biden’s executive order is a good start, the Australian government should establish a Japan–US–Australia dialogue to ensure a collaborative national policy response to rare-earth supply issues. Such a response needs to promote equity investments and green technologies for the mining and production of rare earths in Australia’s north that will support a shift to greater global competition and diversification away from China.

Like a Jim’s Mowing franchise owner watching a neighbour lay synthetic grass, many Australian business leaders with multiple lines of dependency on Chinese money have looked on with disdain and disappointment as the bilateral relationship has deteriorated beyond recognition in recent years.

It has taken overt bullying from Beijing over a long period for most to realise that trade sanctions against Australia are symptomatic of a deeper problem that is not going away, and that there’s very little short of total capitulation that our political leaders can do to get back on China’s good side.

Now, in light of more genuine concern about Beijing’s worldview and the prospect of the global power balance shifting decisively in China’s favour, some of the negative energy corporate Australia had stored up over Canberra’s perceived mishandling of the bilateral relationship is being directed to more constructive ends.

This is good news on several fronts.

That our business leaders are working hard alongside government to reassess the strategic risks of the Australia–China trade relationship, including the costs and complexities of diversifying our China-centric export and supply chains, signals a need, if not a desire, to act with more unity of purpose on China than we have done in the past.

That we are starting to see some Australian business elites publicly denounce China’s social-control practices, including the recent criticism by mining magnate Andrew Forrest’s Minderoo Foundation of China’s mistreatment of its Uyghur minority population in Xinjiang province, signals a recognition of the collective responsibility to more appropriately balance economic and national security considerations.

That you only see the term ‘hawks’ used these days in narrowly focused articles written by big-business types claiming to have come up with the one ‘serious’ proposal for mending the bilateral relationship points to a maturity in our public discourse that is long overdue.

Taken together, these developments are important for what they say about our capacity to adapt to changing circumstances.

The message is this: we are collectively worried about China’s nationalist rhetoric and efforts to permanently reshape the strategic landscape of the region. So much so that the fragmentation along economic and national security lines that has long allowed Beijing to frame situations in ways that distort our decisions and prevent us from developing a broad consensus on critical issues is no longer the defining feature of Australian politics that it once was.

It is easy to forget how far we have come with all of this.

Adopting a ‘conciliatory line’ on China used to mean avoiding issues that might upset Beijing and thus potentially jeopardise our economic and trade ties. Now it means standing up for our national interests in ways that are not needlessly combative or provocative.

The notion that Australian business leaders could ever be reluctant to engage in public debate about China for fear of being dismissed as apologists was simply unimaginable five years ago, when the voices of those worried about over-reliance on China were being systematically drowned out.

But here we are, by and large all in furious agreement that lacking a commitment to consistency on China is a luxury we can no longer afford and that there is no alternative to protecting Australia’s sovereignty, even if we disagree on the methods for doing so.

Closer alignment between Australian policymakers and business leaders is an overwhelmingly good thing for Australia. The question now is can it be sustained over time.

Xi Jinping’s control over the China Coast Guard, together with a new law that authorises the coastguard to use force against foreign ships in places China defines as in its own, is a big change that has so far attracted far less attention than it deserves.

Maybe that’s because Xi has acted on several fronts to assert Chinese power and take risks in the dying weeks of Donald Trump’s term as US president and in the early days of Joe Biden’s tenure. Some moves—like the one to put sanctions on senior Trump officials, their families and companies that employ them—have rightly attracted attention as vindictive measures. Others, like the People’s Liberation Army’s incursions into Taiwanese airspace, are about furthering Beijing’s campaign to isolate and intimidate Taiwan and test US and international resolve.

Taken together with these moves, Xi’s boldness with the coastguard shows that he’s ratcheting up the risk he’s willing to take in confronting other nations and using the levers he has to project Chinese power. And the coastguard move is one that gives him very practical new tools to cause damage and insecurity and act in ways that others—particularly militaries—can’t, and probably shouldn’t, match.

Chinese state media has downplayed the law, saying it’s similar to other nations’ practices—but it’s not, because it signals that the Chinese state will ignore international law of the sea and international tribunal rulings when using force and define the coastguard’s jurisdiction to use force through China’s unilateral characterisation of its maritime boundaries. And the way the Chinese coastguard is likely to operate in practice will be quite different too.

We’ve got used to stories of Chinese fishing fleets and Chinese militia vessels intimidating other nations’ vessels and even bumping into them to get their way, particularly in the South China Sea in waters claimed by Vietnam and the Philippines, but also down into the Natuna Islands in Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone.

Chinese vessels have sunk Philippine and Vietnamese fishing vessels in the last year, and not seemed too bothered about meeting obligations to provide assistance to sailors needing help afterwards. We’ve also got used to the Chinese coastguard shadowing Chinese fishing fleets, ready to intervene if they come into contact with other nations’ vessels.

What’s different now, though, is that with this new law Xi has told his coastguard to be wolf warriors at sea—and to use force, including lethal force, to assert Chinese interests.

The Chinese coastguard has been building some novel ships that let it apply force not just with the weapons on board, but with the ships themselves. Coastguard vessels like the 10,000-ton Haixun aren’t just bigger than many naval ships operating in the South and East China Seas, but they also have strengthened hulls that are designed for deliberately hitting other vessels—‘shouldering’ is the naval term of art.

Imagine a specially designed large vessel like the Haixun ‘shouldering’ a Vietnamese, Philippine, Indonesian or even US naval vessel, enabled by Xi’s law and his command to Chinese agencies and officials to engage in a difficult ‘struggle’ against the world.

Ships operated by those navies (and the Royal Australian Navy) don’t have such strengthened hulls. They’re designed to withstand some damage, mainly from weapons—and the primary approach is to prevent missile hits.

To see the kind of damage a collision with a large vessel causes to such ships, we’ve got the example of the Norwegian frigate Ingstad, which collided with an oil tanker in 2018 before being deliberately grounded and sinking. The images tell the story. It ended with the frigate being scrapped because the damage (from the collision and from being underwater for four months) was too extensive to be repaired.

So, we may need to be thinking less about the Chinese coastguard firing on other nations’ vessels and more about how to handle coastguard commanders who are full to the brim with wolf warrior spirit and licensed by Xi to get into trouble, and how to deal with ships designed to hurt others without using their weapons.

The ability to inflict damage without weapons gives the Chinese coastguard the easy ground in an encounter. A naval vessel that can’t bump back without damaging itself is left with the choice of backing off and handing the encounter to the Chinese or using its weapons and being the first to fire. Neither is a great place to be.

The Chinese coastguard’s use of this new law and its ships in this way might get cheers in Beijing and make strident nationalists there happy. But if any Chinese leader thinks this ‘nonlethal’ use of force is a low-cost, politically free good, that would be a mistake.

Coastguard ships bumping into, damaging and perhaps sinking not just fishing vessels but other countries’ naval vessels would be a hugely escalatory and aggressive set of behaviours, especially in contested waters, no matter how Beijing characterises them. Maybe Xi needs to hear this from the leaders of other countries before we start seeing such antics on the water.

More crystal-clear Biden phone calls to Xi, and maybe calls from leaders like German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who could mention it while celebrating investment agreements, are paths here. In his first conversation with Biden, Xi said the US needed to show caution—well, that’s a message he might take up himself.

At a basic tactical level, capturing video of the Chinese coastguard in action on smartphones and developing a communication plan that gets that footage out before Beijing spins disinformation tales of ‘It wasn’t us. It didn’t happen. They did it first’ also make sense.

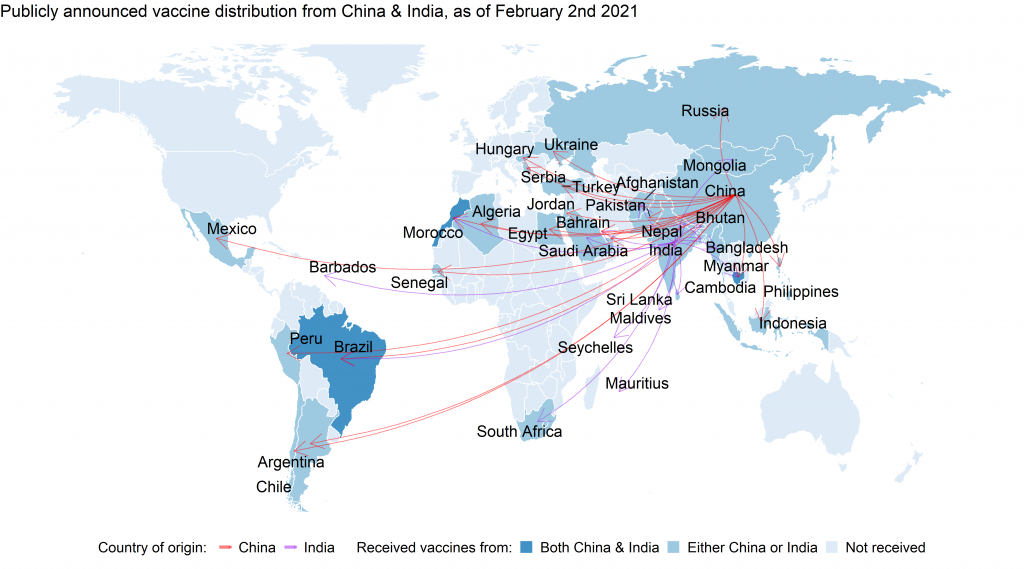

China and India are using the inoculation drive against Covid-19 as part of their diplomatic efforts to shore up global and regional ties—and they aren’t the only ones. But now the two countries are engaged in a tussle playing out online and in the media over the messaging around their respective vaccine candidates, reflecting an emerging flashpoint between the two powers.

Both countries have approached vaccine development and distribution as a matter of national pride. China has a number of candidates, including CoronaVac, made by the pharmaceutical company Sinovac. Another, made by Sinopharm, has been approved for use in China. India’s Serum Institute is manufacturing doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine, known locally as Covishield. And Bharat Biotech International and the Indian Council of Medical Research have developed a vaccine known as Covaxin.

India has a long track record of vaccine manufacture and launched a ‘neighbourhood first’ policy for Covid-19 vaccine distribution, with reported plans to send supplies to Mongolia and Pacific island states as well as Myanmar, Nepal and Sri Lanka. This soft-power initiative has been characterised by some as a bid to counter China’s growing influence in the Indo-Pacific and its push to distribute vaccines and medical supplies in the region.

On Twitter, Chinese diplomatic accounts have hailed reports of the arrival of its vaccines in countries like Sri Lanka and Cambodia. China reportedly plans to distribute 10 million coronavirus vaccines overseas as part of the COVAX initiative, primarily in developing nations. Meanwhile, Indian politicians have been using the hashtag #VaccineMaitri—or vaccine ‘friendship’—to celebrate Indian-made vaccines as they head for places like Brazil and Bangladesh. In January, posts using the #VaccineMaitri hashtag attracted at least 541,000 interactions on Facebook, according to the social analytics platform Crowdtangle.

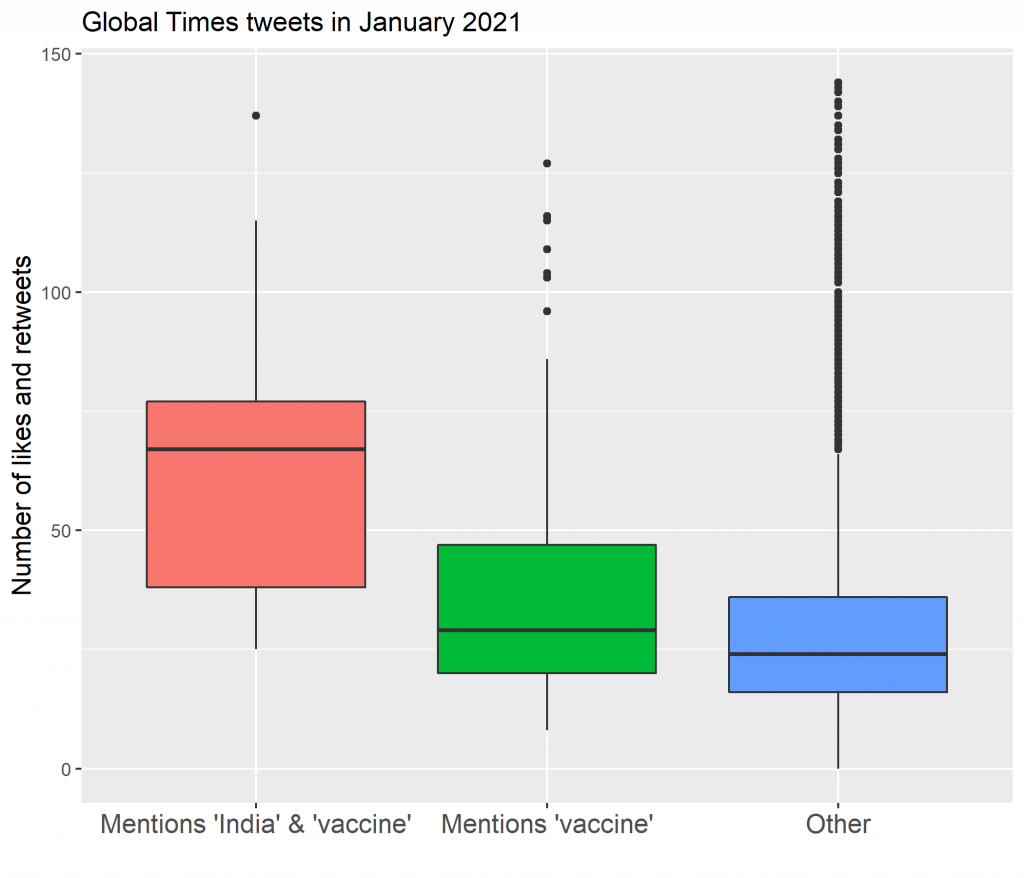

As the global vaccine rollout ramps up, state-linked social media accounts and media outlets in both countries have amplified negative narratives about their competing vaccine candidates. The Chinese Communist Party–linked Global Times, for example, has published more than 20 stories mentioning India and vaccines in January in its English-language edition. Global Times pieces have spotlighted ‘safety and efficacy’ concerns about India’s vaccines, contrasted with a piece about how Indians in China are embracing China’s vaccines. Another said, ‘New Delhi could take note that vaccines should not be a geopolitical tool and vaccine exports is not a contest.’ On 25 January, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesman Zhao Lijian was asked about India’s ‘vaccine diplomacy’ at a press conference and decried ‘malign competition, let alone the so-called “rivalry”’.

This messaging from Chinese media and officials has set off a war of opinion pieces. The Times of India accused China and the Global Times of starting ‘a smear campaign’ against India’s vaccines. India’s News18 claimed that the Global Times was ‘rattled by New Delhi’s “Vaccine Maitri” initiative’ and that the world sees India ‘as a benevolent friend’. A headline on another Indian television network declared ‘Some Spread Disease, Some Offer Cure’, according to the South China Morning Post, referring to reports that Covid-19 first spread from China—a sentiment echoed by some Indian politicians online.

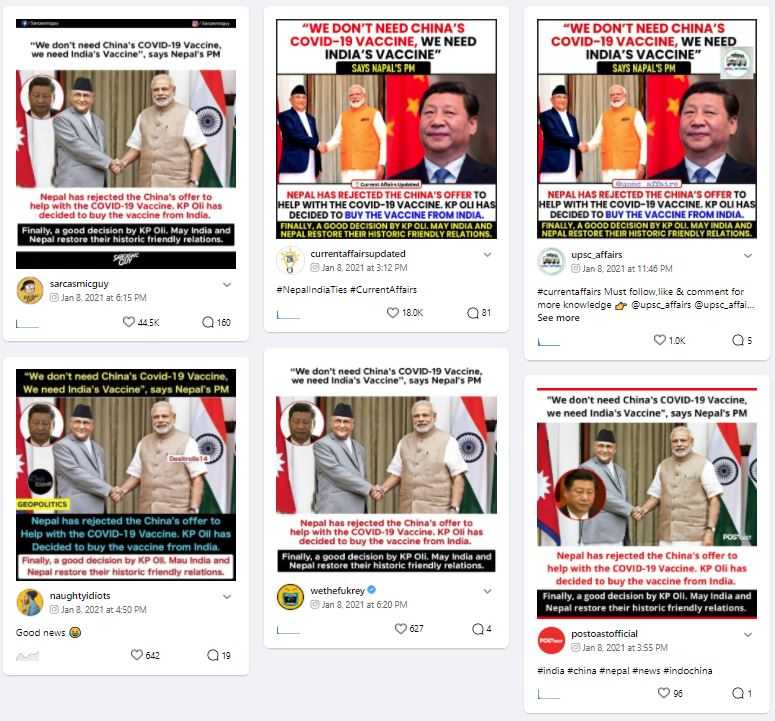

In some cases, tension has emerged over countries in which India and China are competing to provide vaccine access. For example, some Indian news outlets claimed that Nepal ‘preferred’ India’s vaccines over China’s, an idea that was also reflected in a variety of memes on Facebook, including some that included a quote credited to Nepal’s Prime Minister K.P. Sharma Oli that is unsourced and unverified. The country has long been the focus of geopolitical maneuvering between its two powerful neighbours. Versions of the post also appeared on Instagram, where a sample of six posts received more than 65,000 interactions, according to Crowdtangle.

Another meme that was shared across Facebook, including by a number of Indian political meme accounts that often share pro-government content, sought to amplify negative narratives about other vaccines, contrasting them to those made in India. The meme highlighted the supposed link between recent deaths in Norway and the Pfizer vaccine—a narrative that’s also been used this year by Russian and Chinese government-linked accounts—despite no definitive evidence of cause and effect.

The Cambodian government, which typically has close ties with China, reportedly requested doses of India’s vaccines. After a speech on Cambodia’s Covid-19 response from Prime Minister Hun Sen that was interpreted by some news outlets as a rejection of China’s vaccines, the claim was strongly rebutted by China-linked social accounts. Tweets from a reporter for Chinese state media about the issue were retweeted by foreign ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian. CCP diplomatic accounts later celebrated the arrival of China’s vaccine in the country.

In response to Global Times articles about India’s vaccine drive, pro-Indian netizens have dominated the comments sections of the outlet’s social media posts. On Twitter, an analysis of 3,200 Global Times tweets in January found that those mentioning ‘India’ and ‘vaccine’ had on average more likes and retweets than those on other topics. Many of these retweets were ‘quotes’ where pro-India accounts retweeted Global Times tweets with comments supporting Indian vaccines or criticising Chinese-produced vaccines.

Likewise, articles posted on the Global Times Facebook page have been inundated by pro-Indian accounts boasting about the countries receiving Indian-manufactured vaccines or criticising the efficacy of the Chinese vaccines. One Facebook post by the Global Times that shared a link to a story alleging a ‘rocky road ahead for New Delhi’s vaccine export campaign’ received more than 400 comments, many with a version of the sentiment ‘China made the virus, India made the vaccine’—a phrase also used in some Indian media. ‘You exported the virus. India exporting vaccine’, another said.

Likewise, articles posted on the Global Times Facebook page have been inundated by pro-Indian accounts boasting about the countries receiving Indian-manufactured vaccines or criticising the efficacy of the Chinese vaccines. One Facebook post by the Global Times that shared a link to a story alleging a ‘rocky road ahead for New Delhi’s vaccine export campaign’ received more than 400 comments, many with a version of the sentiment ‘China made the virus, India made the vaccine’—a phrase also used in some Indian media. ‘You exported the virus. India exporting vaccine’, another said.

Tensions between India and China have been ongoing across a variety of fronts, not limited to vaccine distribution. Border skirmishes have continued between the two powers in the Himalayas, including a deadly clash in mid-2020. India has also banned TikTok and other Chinese apps over claims the apps were ‘prejudicial to sovereignty and integrity of India, defence of India, security of state and public order’.

Vaccine diplomacy, as well as vaccine nationalism, are likely to continue rising in 2021 as immunisation programs get underway globally. Wealthy countries have secured a significant number of doses and there are fears that poorer nations will be left behind. Medical experts have expressed concern about some Chinese and Indian vaccine candidates, largely over a lack of transparent testing data and the risk of premature approval, respectively. Yet while access to Covid-19 vaccines and transparency about their efficacy and safety are priorities, influence operations that seek to demonise or cause confuse about certain vaccine candidates could complicate such initiatives, creating a risk to public health.

Sino-American rivalry bodes ill for Singapore’s politics and security but the storm has a few silver linings.

A ‘tech rush’ of sorts is manifesting with Chinese technology giants like Alibaba, Tencent and Bytedance (the owner of TikTok) expanding their presence in Singapore, alongside their American competitors.

The shift in global value chains creates opportunities for Singapore to reach out to both sides of the Sino-American competition and attract and anchor investment across ASEAN as a non-China alternative. This is notwithstanding that the bifurcation of technology and supply chains would be detrimental to economic efficiency and potentially to the unity of ASEAN if different members align more with one side or another.

The motivating factors for these shifts are mainly geopolitical, and the danger remains that Singapore and other countries will be pressured to align with one side or another. If so, what will Singapore decide? This has been a central geopolitical concern in Singaporean thinking about its security and remained a live question throughout the past year.

Generally, Singapore worked hard to engage with former US president Donald Trump’s administration and, compared with many others in the region, is more like-minded about the need to balance against China.

Yet even to Singaporean observers, there have been many signs that suggest a trend of US disengagement—most apparent in the American leader’s absence at the annual East Asia Summit, hosted by ASEAN, since 2018. That trend is expected to be reversed to some degree under President Joe Biden.

In contrast, China’s engagement with the region has continued and indeed stepped up with the Belt and Road Initiative as well as with assistance in dealing with the pandemic. Singapore is actively participating in the financing of many BRI activities and more broadly as a hub for China’s growing business presence in ASEAN.

Singapore’s articulation of the Sino-American question is changing, even as it continues fundamentally to advocate for American engagement in the region. In a 2020 Foreign Affairs article on ‘The endangered Asian century’, Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong acknowledged how China’s stake in the region has grown: ‘Increasingly, and quite understandably, China wants to protect and advance its interests abroad and secure what it sees as its rightful place in international affairs.’

The adjustment in comments on the South China Sea is noteworthy: statements made by Singapore immediately after the South China Sea arbitration in 2016 drew a stern reaction from Beijing; by comparison, when US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo formalised support for the tribunal ruling rejecting China’s maritime claims in the South China Sea, Singapore and ASEAN were relatively muted.

More than a few countries in the region are rethinking their policies towards China and the US.

For Singapore, while fundamentals remain in place, nuances may be discerned and there’s considerable debate and divergence among prominent former diplomats and public intellectuals.

Singapore’s fundamental position is that countries shouldn’t be forced to choose one side or the other, linked to an emphasis on the importance of an open regional architecture, in which influence is never exclusive and deepening ties with one does not mean going against the other.

The ability to engage multilaterally has worked in a rules-based international order that has helped small and middle powers to thrive. There’s concern that this multilateral system is fragmenting—and ironically because of actions taken by the US, which has been the maker and mainstay of that order.

Many in Singapore remain cautious about talk of a ‘Cold War 2.0’; while conflicts didn’t occur on Soviet Union or American soil, proxy conflicts were found in the Asia–Pacific theatre.

Even short of war, the dangers of a war mentality applied to Sino-American competition are manifold. They include a legitimation of breaking the normal rules so that it’s only power and might that matter, the forcing of an either/or choice in relations, and the weakening of international institutions.

Singapore has been watchful over the undermining of the Paris climate agreement, and responded by stepping up commitments to address climate change in tandem with partners. Similarly, the weakening of the World Trade Organization and the World Health Organization are major concerns. With the weakening of the WTO, Singapore has joined in the ‘multi-party interim appeal arbitration arrangement’ to the WTO—a coalition that is broad but which in Asia initially includes only China, Hong Kong, Australia and New Zealand.

In the WHO context, Singapore is notably involved in COVAX—a global vaccine initiative to distribute 2 billion doses of Covid-19 vaccines around the world by the end of this year. These efforts point to a wider strategic response that Singapore is making in the current security context: to reach out to and work with other non-great powers, especially ASEAN and Asian partners (with continuing ties with Japan and India and an uptick in engagement with South Korea), as well as the European Union and others further afield.

Most analysis in Singapore points to the clear bipartisan support for the US to continue to be tough on China. In this regard, 2020 was a critical year for the broader re-examination of Singapore’s relations with both the US and China, and what Singapore and other countries can and should do.

The pandemic has sharpened that awareness and accelerated the trends. Singapore can wish but can’t directly improve the US and China relationship. But it has sought to increase its abilities to secure its own position if relations continue to deteriorate. This is not only in dealing with the two great powers, but also in its efforts for regional community, a rules-based international order and working with other countries.

These efforts are set in the context of avoiding a ‘war’ mentality, and the need to build consistent and steadfast engagement with other countries, taking a multilateral approach across a broad range of issues, especially in recovering and reconnecting in the wake of the pandemic.

For the security not only of Singapore but of many of the countries caught between the US and China, there’s nothing more, and nothing less, to be done.

America and China should cooperate in space. Although the United States can no longer take its extraterrestrial dominance for granted, it remains the leading player, while China’s space capabilities are growing fast. Most important, both countries, along with the rest of the world, would benefit from a set of clear rules governing the exploration and commercialisation of space.

China made history in 2019 by becoming the first country to land a probe on the far side of the moon. It continues to notch up impressive achievements, most recently its Chang’e-5 mission to retrieve lunar samples. Former US President Donald Trump also took an active interest in space, announcing that America would return astronauts to the moon by 2024 and creating the Space Force as the newest branch of the US military.

The next phase of competition in space will be to establish a mining base on the moon. Lunar mining is important for two reasons. First, ice on the moon’s surface can be converted into hydrogen and oxygen and used as rocket fuel, which is crucial for deep-space missions.

The second reason is closer to home: the moon’s surface contains highly valuable rare-earth metals that are used in technologies like mobile phones, batteries and military equipment. China currently produces approximately 90% of the world’s rare-earth metals, giving it significant leverage over other countries, including the US. By sourcing these metals from the moon, countries could reduce their dependence on China.

Historically, mining and any other claims to objects in space were considered to be prohibited by Article II of the 1967 United Nations Outer Space Treaty (OST), which states that ‘outer space […] is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means’.

This agreement resulted from collaboration between the US and the Soviet Union, the two leading space powers at the time. Despite their rivalry, they were able to establish a framework for space exploration that prevented militarisation and, inspiringly, regarded astronauts as ‘envoys of mankind’. The hotly contested space race continued—as did the larger Cold War—but with norms in place to protect the common good.

This regime began to fracture after the adoption of the 1979 UN Moon Agreement, which sought to place private commercial claims to space resources under the purview of an international body. No major spacefaring power ratified the accord, and the legality of private claims in space remained murky. Then, in 2015, the US Congress granted US citizens the right to own any materials they extract in space, opening the door for commercial space exploration.

In October, Trump took matters even further by initiating the Artemis Accords—a set of bilateral agreements between the US and Australia, Canada, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, the United Arab Emirates and the United Kingdom that set out principles for future civil space exploration. The accords claim to affirm the OST, but actually expand the US interpretation of commercial space law by stating that mining ‘does not inherently constitute national appropriation under Article II’ of the treaty.

With these accords, the US and the other signatories are bilaterally—and dubiously—interpreting an international treaty, and attempting to determine future commercial interests in space without a multilateral agreement. Absent international standards, countries could engage in a race to the bottom in order to gain a competitive advantage. Unregulated commercial activity could cause a host of problems, from orbital pollution that jeopardises spacecraft to biological contamination of scientifically valuable sites.

Moreover, the Artemis Accords deliberately circumvent the UN to avoid having to include China, thus souring international space relations just when cooperation is needed to tackle common challenges. China has historically been excluded from the US-led international order in space. It is not a partner in the International Space Station program, and a US legislative provision has limited NASA’s ability to cooperate with it in space since 2011.

If the US managed to coordinate with the Soviet Union on space policy during the Cold War, it can find a way to cooperate with China now. The two countries will likely remain at odds on many issues, including trade, cybersecurity, internet governance, democracy and human rights. But President Joe Biden’s administration must also recognise those areas where cooperation is in America’s best interest. Global threats like pandemics and climate change are obvious examples; setting norms for commercial activities in space is another.

As a first step, the new administration should distance itself from Trump’s accords and instead pursue a new course within the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. Biden can restore some of America’s global legitimacy by working to establish a multilateral framework, negotiated with all relevant parties, that protects areas of common interest while granting internationally accepted commercial opportunities.

This will not be an easy task, given that US–China relations are at their lowest point in decades. But the alternative is bleak. Without an international framework that includes all major spacefaring countries, the moon could become the next Wild West. China is unlikely to be a responsible partner in a space order that does not afford it a position. Isolating China could even lead to a territorial clash with the US over prime real estate at the moon’s south pole, where precious ice reservoirs are thought to be located.

The wonder of space inspired rival powers to work together in the interest of mankind once before. With effective leadership in the US and China, it can happen again.

ASPI’s executive director, Peter Jennings, has warned a United States congressional inquiry that China may trigger a major military crisis over Taiwan in the coming year as the Chinese Communist Party’s centenary looms and the US faces a terrible domestic health situation due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

In a series of written responses to questions from the US–China Economic and Security Review Commission today, Jennings says he believes the CCP will continue to test the boundaries of international patience in its operations against Taiwan and in the first island chain until the US and its allies feel compelled to attempt to limit Beijing’s behaviour.

A failure of the US to respond would challenge its credibility as a security partner.

At any time, Chinese President Xi Jinping could reduce the rhetorical tone and limit the People’s Liberation Army’s military exercises and air incursions, Jennings says, but Xi stands to lose nothing if he keeps testing the limits.

‘This gives rise, in my view, to a possible major crisis on Taiwan or the East China Sea in 2021.’ Jennings says Beijing will have developed a menu of options to pressure concessions from Taipei related to its political autonomy. ‘This does not have to involve a PLA amphibious assault of Taiwan’s northern beaches, but it could involve maritime blockades, closing airspace, cyber assaults, missile launchings around (and over) Taiwan, use of fifth column assets inside Taiwan, use of PLA force in a range of deniable grey-zone activities and potentially seizing offshore territory—Quemoy and Matsu, Pratas, and Kinmen Islands. Beijing will continue to probe with military actions, test international reactions and probe again.’

This threat must be seen against the background of China’s efforts to build soft power globally through its own foreign-language media outlets, Confucius Institutes, local organisations linked to the United Front Work Department and, above all, financial relationships, Jennings says.

He notes that, for many countries around the world, China’s global appeal is calibrated against the global attractiveness and effectiveness of the US. ‘Key Southeast Asian countries will make judgements about the need to hedge their relations with Beijing based on the level of confidence they have that the United States is engaged with the region and committed (for reasons of its own interests) to Asian security. A Southeast Asia that doubts the longevity of American interest will get closer to the PRC regardless of the appeal of doing so.’

In response to the commission’s request for recommendations to deal with this situation, Jennings says the CCP presents a profound threat to democratic systems and the international rule of law everywhere. To counter malign CCP activities, like-minded democracies must align and commit to a shared sense of purpose.

‘As Australia saw over 2020, Beijing works hard to split democracies apart from each other and to weaken their resolve through bilateral pressure. My view is that the Commission can play an international role by cooperating more closely with like-minded democratic legislatures including, of course, the Australian Parliament; sharing information and generally emphasizing that we must work together to address a global threat. The Commission might consider establishing a regular dialogue on the PRC for legislatures from the Five Eyes countries.’

The commission could engage with Australia’s parliament through the House speaker and the Senate president on a shared research agenda. That would use parliament’s high-quality and relatively well-resourced committee system, which operates in a largely bipartisan way on national security matters, says Jennings.

He says Southeast Asia is emerging as one of the most critical zones of global competition for influence between the US and the CCP. ‘Beijing sees the region as key to its security, which is why it made such an audacious move to annex the vast bulk of the South China Sea. For Japan and Australia, the free passage of trade through and over the South China Sea is an existential strategic interest.’

If the US is denied access to the region (which also includes treaty allies Thailand and the Philippines), America’s capacity to shape positive security outcomes in the western Pacific is deeply eroded. Beijing knows this and is actively engaged in trying to tilt the region away from the US, says Jennings.

The next two years will shape US success or failure in Asia, he says, and the commission should focus on building deeper knowledge about Beijing’s efforts in the region and a deeper appreciation of the strategic outlooks from the 10 Southeast Asian capitals.

‘America’s challenge is to give the Southeast Asian countries a sense that they have a realistic alternative to accepting Beijing’s dominance and that the democracies will continue to support … their sovereignty and security.’

Jennings suggests that the commission work with Australia to develop a plan to help vulnerable Pacific island countries (PICs) resist CCP pressure.

As in World War II, these nations remain strategically important in shaping how US forces can access and operate in the western Pacific. Beijing understands this too, which helps to explain why it has invested so quickly and substantially into building relations with PIC political elites, Jennings says.

Through its Pacific step-up policy, Australia is re-energising its own PIC engagement strategy, but all like-minded democracies can play a role. US Indo-Pacific Command and other US agencies have lifted their interest and activity with the PICs, and that engagement could be enhanced with more congressional help and support.

Jennings says the PICs are fragile societies, often with limited infrastructure, economic and social opportunities. ‘On the plus side, the region overwhelmingly shares our values and has (mostly) stuck to democratic systems.’

Dealing with China’s financial power is one of the biggest challenges the region faces. ‘It would be valuable to consider a joint study with the Australian Parliament on how best democracies can assist the PICs in strengthening their own systems and reducing their vulnerability to coercion and co-option’, Jennings says.

There’s a need to explain to the citizens of all democracies the nature of the challenges they face in dealing with an increasingly aggressive, nationalistic PRC. ‘There is a significant gap between what executive government and security and policy specialists understand on the one hand (which is often based on classified material), and what back-bench politicians and their electors know’, says Jennings.

‘The Commission could play an important role here by distilling its very deep strategic understanding of the issue into a “tool-kit” for elected representatives designed to help them explain the strategic challenge we face to our citizens.’

It seems clear, says Jennings, that Taiwan will face yet more pressure from the PRC in 2021 and later, and we should not be surprised if Beijing confects a cross-strait crisis.

‘It may be that President Xi calculates that a short-term window of opportunity is closing for the PRC to pressure Taiwan to make concessions on its future political status.’

The commission should help provide greater clarity on what the US would do if Taiwan were attacked, Jennings says. ‘My view is that clarity is what is most needed at a time when the PRC might fail to correctly read American policy signals.’

The CCP’s ‘one China’ policy has resulted in such limited Australian engagement with Taiwan that Canberra’s policy thinking about the country and its capacity to make public statements about Taiwan’s security have become stunted. A commission dialogue with Australian counterparts on options for engagement with Taiwan would be valuable, Jennings says.

‘I would expect the United States to stand by its long-held policy disposition to support Taiwan’, Jennings says. ‘On that expectation hangs the credibility of America’s alliance network in the Pacific. To put it bluntly, if the US chose not to vigorously support Taiwan in the face of PRC coercion, this will do immense damage to the credibility of US engagement as viewed in Tokyo, Seoul, and Canberra. That could weaken resolve in these capitals to resist PRC coercion.’