The Quad and AUKUS show messy, creative democracies hard at work

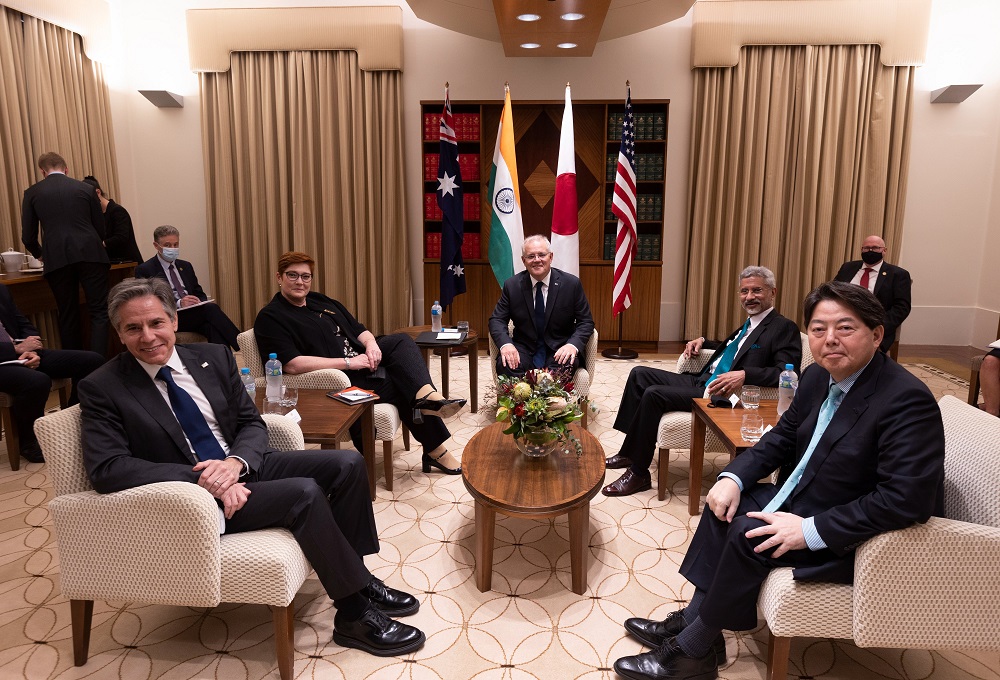

Let’s hope the Quad and AUKUS get boring. It’s rare in the politics of diplomacy to have no new ‘announceables’ or major initiatives from key meetings like the Quad involving Indian, Japanese, American and Australian foreign ministers in Melbourne on Friday. It’s even rarer for that to be a fine thing.

But Melbourne has hopefully set a pattern for other Quad meetings in 2022—a focus on hard work, implementation and delivery, with a common, positive purpose, and without the need for shiny new talking points.

Reading the joint statement and remarks after the meeting, the agenda is clear and the work is coming together, as is a sense of optimism and energy. That optimism contrasts starkly with the defensive tenor of much of the last five years, when China had seemed to have the momentum and others were mainly just responding.

Last year saw major new strategic developments and groupings, with the big two being the Quad leaders’ group brought together twice by US President Joe Biden with prime ministers Narendra Modi, Scott Morrison, Yoshihide Suga and then Fumio Kishida, and AUKUS—brought into being by Biden, Morrison and UK PM Boris Johnson. This year and the next must see action and effort on the agendas of both these ‘minilaterals’.

The good news is that even on their way to Melbourne the US, Indian and Japanese ministers all knew this. Indian reporting on External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar put it well, saying the Quad would be ‘operationalised in Melbourne’, with the agenda being ‘to translate its discussions and objectives on the ground, be it vaccine delivery [or] critical and emerging technologies’.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken told reporters on his plane: ‘The Quad is becoming a powerful mechanism for delivering, helping vaccinate a big part of the world and getting a lot of vaccines out there, strengthening maritime security to push back against aggression and coercion in the Indo-Pacific, working together on emerging technologies and making they sure they can be used in positive ways not negative ways’.

Japanese reporting had a similar tone, also noting that Foreign Minister Yoshimasa Hayashi would continue on after the Quad meeting to Honolulu to continue work with Blinken on Indo-Pacific security. Blinken and Hayashi were joined there by their South Korean counterpart, Chung Eui-yong.

All this is evidence that our region’s most powerful democracies have moved from thinking and proposing to implementing and acting. That’s enormously positive and energising, and sorely needed not just in the Indo-Pacific but in the wider world.

It’s also more than noteworthy that the US, in particular, is devoting this leadership time and attention to the Quad and our region while also bringing so much bandwidth to bear on deterring Russia in Europe. We need to get less surprised about the ability of this great power to walk and chew gum. And we also need to understand a new phenomenon that is strangely making this easier.

On 4 February, Russian and Chinese leaders Vladmir Putin and Xi Jinping chose to use their lonely time together at the Winter Olympics to tell the world that their coercion of those around them—whether of Ukraine, Taiwan or other neighbouring states—was actually conscious and concerted behaviour, and that we should expect to see more of it as their partnership deepens.

In their lengthy joint statement, among anxious words about ‘colour revolutions’ and fears of external enemies, Xi and Putin tried to convey a picture of themselves to the world as cosy, empowered autocrats, confident enough to pretend that authoritarianism is democracy, aggression is pacifism and political repression is protection of human rights.

The two problems they have are that simply saying all this doesn’t make it true, and the disconcerting fact that the world’s real democracies are graphic demonstrations of what actual freedom looks like: creative and messy, but powerful.

We should thank both Putin and Xi for focusing the efforts of an otherwise diverse set of democratic groupings and powers across NATO, the EU, the Quad and AUKUS in common directions—and for showing us all the connections between what happens in Europe and what happens in the Indo-Pacific.

Funnily enough, another common cause Putin and Xi were less vocal about is also present right now in the febrile climate of an approaching federal election: foreign interference in our political system. Because Australia is not an isolated target of this work, it’s another phenomenon that will drive European and Indo-Pacific partners closer together

While they protest their non-interference commitments, both Russia and China are capable and large-scale perpetrators of covert and corrupting interference inside other nations’ policymaking and political machineries. Russian interference in US politics is formally documented and the activities that led to Australia’s foreign interference laws have been reported extensively—with some prime examples collected in Peter Hartcher’s excellent book Red zone.

Just last week, ASIO chief Mike Burgess said espionage and foreign interference have outpaced terrorism as the greatest threats his agency is dealing with. While other states with ‘sharp elbows’ (as Burgess called them) are also involved, the two big players are Russia and China. There are conflicting accounts about whether one particular plot recently disrupted by ASIO was Russian or Chinese. Sources within intelligence agencies seem to have confirmed it was Beijing, but this or another plot could just as easily have been Russian.

In 2022, AUKUS is showing a similar shift from aspiration to hard, focused delivery work. Five months of the 18-month implementation planning period the AUKUS leaders announced back in September have already sped by.

Among other signs of progress—like a three-nation nuclear information-sharing arrangement—Australia is putting additional diplomats into Vienna to do the heavy lifting around protecting nuclear non-proliferation, while also expanding Canberra-based non-proliferation expertise. That’s no doubt less exciting work than dealing with designing, building and operating nuclear submarines. But it’s essential to get right if Australia is to get the submarines and also implement AUKUS in a way that doesn’t just protect but strengthens the world’s controls around nuclear weapons. Non-proliferation is not a trivial side issue for AUKUS. It’s a core part of how it must be designed and implemented.

With the Quad and the frenetic consultation surrounding deterring and sanctioning Russia over Ukraine, 2022 has started well for those interested in reversing the lazy narrative of declining, divided democracies confronted by confident autocracies.

Australians should take to heart three key facts about this.

It’s remarkably positive that, with the Quad and AUKUS, we are at the table in two of the peak groups that matter to how the regional—and global—order gets rearranged.

That puts a great obligation to do more than just participate in these groupings—we need to invest the resources, talent and simple hard work to make our contributions matter, and to increase the tempo and momentum of delivery of both these groupings.

And aggressive autocrats banding together won’t be deterred by nuanced tones of voice and smiles. Doing so will require clear-eyed cooperation backed by real-world capabilities, measured diplomacy and political will—as well as all the creativity our messy democracy and those of our partners and can bring to bear.