Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

In the Xi Jinping era, the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries (commonly known as the Friendship Association, or Youxie) promotes the Belt and Road Initiative, a strategic, political and economic vehicle driving towards a China-centred global order.

The Friendship Association is a hybrid party–state organisation with three ‘mothers-in-law’ (to use the argot of the Chinese Communist Party system): the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; the CCP united front organisation, the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference; and the CCP’s International Liaison Department, which the party uses to conduct foreign policy discussions with foreign political parties.

The Pacific China Friendship Association is China’s main point of contact for rolling out the Belt and Road Initiative in the Southwest Pacific.

The Pacific ‘branch’ has been busy.

In 2018, at a meeting of friendship associations from the Americas and Oceania in Hainan, China, Tonga’s Princess Royal Salote Mafile’o Pilolevu Tuita proposed establishing a Pearl Maritime Road Initiative, extending the BRI into the Southwest Pacific.

Soon after that, all of Beijing’s Pacific island diplomatic partners signed agreements on the BRI, with infrastructure development the main theme. Some have already started BRI projects.

In 2019, Siamelie Latu, secretary-general of the Tonga China Friendship Association and a former Tongan ambassador to China, announced that the Pacific China Friendship Association was working on a feasibility study for a regional airline to connect all Pacific Islands Forum countries with China.

From Kiribati, to Vanuatu, to French Polynesia, China has repeatedly tried to gain access to militarily significant airfields and ports, all in the name of BRI. Beijing has established military cooperation relations with Fiji, Papua New Guinea and Tonga, and provided police support to Vanuatu and Solomon Islands, frequently in combination with humanitarian aid activities. Just this week, China and Solomon Islands signed a security agreement, despite the protestations of the Australian and US governments.

China is rolling out the Digital Silk Road in the Pacific, using its Pacific embassies to set up ground stations for its Beidou satellite navigation system. Meanwhile, China makes use of commercial operations for Beidou-equipped reference stations in the Pacific. Ground stations and reference stations work together to provide centimetre-level accuracy for satellites. Beidou is China’s GPS equivalent, and it is now on a par with, if not better than, GPS. Like GPS, it’s a military technology, crucial for missile targeting and timing.

The CCP’s political interference and grey-zone activities aim to co-opt Oceanian political and economic elites and to access strategic information, sites and resources in the Southwest Pacific. The establishment of military installations in Oceania could substantially alter the balance of power in the Indo-Pacific. It could cut off the Pacific island nations, Australia and New Zealand from the US and other partners, turning the region into a China-dominated vassal zone.

South Pacific leaders meet regularly to discuss collective security and geostrategic matters—in other words, joint concerns about China. However, their worries about this relationship are usually only hinted at and rarely made public, and their overriding priority tends to be development. China offers assistance with development projects but, unlike most donors, the loan must be paid back, with interest. The Cook Islands, Fiji, Samoa, Tonga and Vanuatu all have crippling levels of debt to China.

Pacific island leaders tend to have a strong sense of history. Few would welcome dependency on China, or the Pacific turning into a Sinocentric order. Yet a degree of reactivity towards calls for vigilance about the CCP’s malign activities is usually couched in anti-European, anti-colonial rhetoric.

Given the continued presence of historic colonial powers in the region, it’s been easy for some to conflate concern about the real dangers of CCP political interference and grey-zone activities—when expressed by ‘Western’ actors—with neo-colonialism and calls of ‘whataboutism’.

This conflation plays into CCP narratives seeking to equate the party with the Chinese people, recasting any critique that it’s inherently racist. But imperial power and racism are by no means a monopoly of Western powers.

There’s real a danger that in their kneejerk response against Western colonialism, Pacific elites will embrace external domination in a new and more dangerous form. The air of schadenfreude that some segments of the Pacific elite display towards ‘traditional’ Pacific powers will be a short-lived pleasure if they can’t transcend this reactionism and recognise the need to plan a way forward in an era of dangerous strategic competition.

Perhaps surprisingly to some, the return of a more active role of the US, UK, Japan, India and the EU in the Pacific, and a resurgence of Australian, New Zealand and French presence and assistance, has been appreciated and welcomed by many Pacific governments. But Pacific leaders want to be treated as equals, not pawns in an international power play, and not as some nameless group of islands in a strategically important region. The US, EU and other partners need to take the time to better understand the individual countries of the Pacific, their histories and their concerns.

It’s especially important that Pacific nations not just be the subject of analysis about CCP political interference in the region. They should be drawn into the international conversation. Pacific civil society must be engaged in this work too, not just governments. In many of the Pacific states, elements within the government are already compromised, and they will not welcome discussions on CCP political interference. Further, CCP united front work is often comingled into corruption and organised crime, which has entangled many political and policy actors, making raising the issues even more difficult.

Pacific journalists also need more support so they can do the due diligence that will enable a factual, informed, depoliticised and public conversation about the CCP’s foreign interference activities in their respective states and territories.

A subset of a pro–Chinese Communist Party network, known for disseminating disinformation on US-based social media platforms, is breaking away from its usual narratives in order to interfere in the Quad partnership of Australia, India, Japan and the United States and oppose Japanese plans to deploy missile units in southern Okinawa Prefecture.

‘Osborn Roland’ joined Twitter in August 2021 and claims to be concerned about the military deployments in Okinawa. A Facebook account named ‘Vivi Wu’—who apparently speaks German, Spanish, French, English and Chinese—says that the Japanese ‘are treated as dogs by the United States’. Korean-named ‘Hag Yoenghui’, who has an Arabic profile description, tweeted: ‘We in Australia originally supported the United States to fight against China, and the relationship with China was extremely tense … Why does our government help the United States to deal with China?’

So far, ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre researchers have uncovered 80 accounts—and counting—across Twitter, Facebook, Reddit and YouTube that since December have posted in multiple languages opposing Japan’s military activities and the Quad. The timelines of these accounts show they previously posted content consistent with the pro-CCP Spamouflage network, which typically targets topics relevant to Chinese diaspora communities and amplifies narratives that align with the CCP’s geopolitical goals.

Past campaigns have focused on smearing Chinese dissident Guo Wengui, denying human rights abuses in Xinjiang and Hong Kong, promoting Buddhist sects supported by the CCP’s United Front Work Department, co-opting the StopAsianHate hashtag and disseminating Covid-19 origin conspiracy theories.

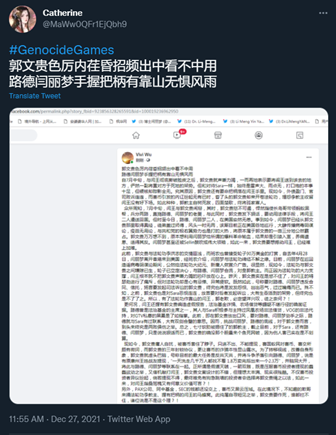

Like with previous campaigns, this network is poorly operated. Errors in hashtags, incomplete URLs to Chinese state media articles and evidence of instructions posted in a tweet are clear indications of coordination and possible automation. One Twitter account named ‘Catherine’ posted a screenshot of their working environment while sharing a Facebook post from ‘Vivi Wu’. The image revealed that the operator of this account saved bookmarks to an ‘offshore navigation and internet access’ (境外导航 –上网从) website and two Canadian Chinese news websites, ‘Anpopo Chinese News’ (安婆婆华人网) and ‘Fenghua Media’ (枫华网), and was closely monitoring Chinese virologist Yan Limeng’s multiple Twitter accounts.

Like with previous campaigns, this network is poorly operated. Errors in hashtags, incomplete URLs to Chinese state media articles and evidence of instructions posted in a tweet are clear indications of coordination and possible automation. One Twitter account named ‘Catherine’ posted a screenshot of their working environment while sharing a Facebook post from ‘Vivi Wu’. The image revealed that the operator of this account saved bookmarks to an ‘offshore navigation and internet access’ (境外导航 –上网从) website and two Canadian Chinese news websites, ‘Anpopo Chinese News’ (安婆婆华人网) and ‘Fenghua Media’ (枫华网), and was closely monitoring Chinese virologist Yan Limeng’s multiple Twitter accounts.

In August last year, Defence Minister Nobuo Kishi confirmed that Japan was emplacing anti-aircraft and anti-ship missiles on Ishigaki Island to defend Japan’s contested southwestern islands and counter Chinese anti-access and area-denial (A2/AD) capabilities that could prevent the US from intervening in a regional conflict. This followed a broader shift in Japanese foreign policy in 2021 which described China’s military assertiveness as a ‘strong concern’ and provoked Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi to suggest Japan was being ‘misled by some countries holding biased view against China’.

In response to these announcements, the network of pro-CCP accounts leveraged local concerns about the environment and the tourism industry in Ishigaki to try to prevent the missile emplacement and suggested Japan ‘was acting as a pawn for the United States’ in an attempt to undermine the bilateral relationship. This included posting photos of atomic bomb mushroom clouds over Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In response to these announcements, the network of pro-CCP accounts leveraged local concerns about the environment and the tourism industry in Ishigaki to try to prevent the missile emplacement and suggested Japan ‘was acting as a pawn for the United States’ in an attempt to undermine the bilateral relationship. This included posting photos of atomic bomb mushroom clouds over Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Other accounts in the network posed as citizens in Australia, India, Japan and the US to criticise the Quad diplomatic partnership by spruiking their economic relationships with China. These covert efforts coincided with a Chinese state media article posted in December arguing that Japanese politicians are ‘attempting to interfere in the Taiwan Straits’ and the ‘international community should be highly vigilant about Japanese right-wing forces’ mentality of playing with fire’.

Some accounts amplified Change.org petitions created in 2019 that sought to stop the construction of missile bases on Ishigaki. By this month, the English-language petition had 312 signatures while the Japanese-language version had more than 6,000. Based on our analysis of previous CCP information operations, we expect pro-CCP accounts in this network to co-opt other similar local petitions and protests. One account has already amplified reporting of a December protest over the use of private ports in Ishigaki by the Japan Self-Defense Forces.

This emerging reiteration of the Spamouflage network has only recently started replenishing with newly created accounts and content, so the impact of the campaign has been low. Most tweets have received at most two interactions and most accounts have fewer than 10 followers. These types of networks, however, can quickly scale up to tens of thousands of accounts and persist on US-based social media platforms for years before being retweeted or amplified by an influential opinion leader or government official. It took Russia’s Internet Research Agency at least two years to prepare before it interfered in the 2016 US election.

This emerging reiteration of the Spamouflage network has only recently started replenishing with newly created accounts and content, so the impact of the campaign has been low. Most tweets have received at most two interactions and most accounts have fewer than 10 followers. These types of networks, however, can quickly scale up to tens of thousands of accounts and persist on US-based social media platforms for years before being retweeted or amplified by an influential opinion leader or government official. It took Russia’s Internet Research Agency at least two years to prepare before it interfered in the 2016 US election.

Twitter has previously attributed these networks to the Chinese government, which makes them useful for gaining insights into the CCP’s broader political and psychological warfare strategies.

Overall, the campaign indicates that the CCP is concerned about the strengthening alignment between countries in Europe, NATO, Asia and the Indo-Pacific following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Eroding alliances such as the Quad, AUKUS, ANZUS and NATO will remain the CCP’s main strategic goal.

It also demonstrates that the network is highly agile and can switch quickly from targeting Chinese diaspora and disseminating propaganda to engaging in military-related information operations and interference in foreign force posturing. Aspects of this campaign sought to shape local domestic Japanese sentiment through intimidation, which is more akin to psychological warfare than propaganda.

Led by United Front Work Departments of Chinese Communist Party committees at each echelon of government, the united front system is a complex and opaque set of organisations designed to advance the CCP’s influence in industry and civil society. Within China, the united front system has several responsibilities, which range from repressing ethnic minorities in Tibet and Xinjiang to grooming members of China’s minor political parties to take up positions in government.

But in addition to its extensive activities inside the country, the united front system acts as a liaison and amplifier for many other official and unofficial Chinese organisations engaged in shaping international public opinion of China, monitoring and reporting on the activities of the Chinese diaspora, and serving as access points for foreign technology transfer.

Many Chinese government-affiliated agencies that are not directly part of the united front system also work to advance the CCP’s influence abroad. A recent study by Sinopsis demonstrates the involvement of entities from united front, propaganda, trade, foreign affairs and intelligence agencies in CCP influence work, indicating that it’s not centralised in one specific, dedicated organ.

This article, however, focuses narrowly on the united front system and its foreign-facing role, and highlights examples of its activities in Europe and North America.

One of the united front system’s most important tasks is to shape international public opinion of China—through both elite capture and public diplomacy. Sometimes, this influence is exercised overtly. In January 2022, for example, the United Kingdom’s security service warned that a solicitor affiliated with the united front system had donated £420,000 to a British MP. In other cases, united front affiliates have offered foreign politicians campaign contributions, engaged directly in lobbying and made significant investments in overseas media outlets.

More often, however, the united front system prefers to operate with some plausible deniability, by funding or co-opting interest groups designed to promote solidarity among members of the Chinese diaspora. In some cases, these organisations—such as trade guilds, student groups and ‘friendship associations’—engage in political activity designed to shield the CCP from criticism, or to protest policies unfavourable to the Chinese government. In the US and UK, for example, Chinese student and scholar associations have pressured university administrators to cancel visits from the Dalai Lama, counter-protest the CCP’s annexation of Hong Kong and censor artwork criticising the party’s actions in Xinjiang.

Public records confirm that, in some cases like that of the Hunan Overseas Friendship Association, these organisations are simply run and paid for by United Front Work Departments of the CCP; more often, however, the party acts to co-opt and politicise groups that operate independently, by offering media promotion and financial or logistical support from the local Chinese embassy or consulate.

Although many organisations affiliated with the united front system are not directly controlled by the CCP or Chinese government, they are best viewed as government-organised non-governmental organisations (GONGOs). These groups also aid in the united front system’s second major overseas mission—monitoring the activities of the Chinese diaspora and silencing dissidents based abroad. In 2020 and 2021, for example, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and Canadian Security Intelligence Service both warned that the Chinese government was using ‘state entities and non-state proxies’ to ‘threaten and intimidate’ activists and Chinese dissidents in the US and Canada. Under the guise of a global anti-corruption campaign called ‘Operation Fox Hunt’, Chinese authorities have succeeded in repatriating 680 individuals back to China, including by threatening their family members.

Not all the united front system’s overseas activities are concerned with the above-mentioned forms of malign influence. Perhaps least appreciated is its role in China’s quest to absorb foreign technology. Local budget documents clarify that the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology coordinates with united front–affiliated GONGOs to promote ‘scientific and technological cooperation and talent development’.

Moreover, as my colleagues and I wrote last year for the Center for Security and Emerging Technology, China’s ‘science and technology diplomats’ (科技外交官)—staff based in the science and technology directorates of Chinese embassies and consulates worldwide—often interface with elements of the united front system in the countries where they are stationed, and rely on their references to identify technology projects of strategic consequence to the Chinese government. Some group members consult remotely for state-owned tech companies in China, while others act as talent scouts and encourage Chinese living abroad to apply for state-run talent recruitment plans. Prior research identified such united front–affiliated groups operating in France, Germany, Italy, Switzerland and the UK and across Scandinavia, though the number of target countries and active organisations increases each year.

On balance, the united front system represents a formidable tool to advance Chinese influence, power and access to technology abroad. Many of its activities are best described as extralegal or ‘grey zone’ operations and are difficult to mitigate at scale. Liberal democracies should coordinate and think of novel ways to blunt the impact of China’s influence operations and stymie unwanted technology outflows.

Russia’s terrible invasion of Ukraine is looming over the Indo-Pacific with its lessons for Taiwan’s relations with China. Some of those lessons are important reality checks. Assumptions about a nominally superior military force have been tempered by a recognition that the details of logistics, tactics, morale and the utility of weapons systems can shift the military balance.

Similarly, Ukraine shows how the impact of economic disruption and sanctions from a regional conflict is global. Taiwan by itself accounts for a greater percentage of global trade than all of Russia, and in sectors critical to global innovation and technological progress, so the disruption of a cross-strait war would also be global and measured in decades.

And the invasion demonstrates how history and identity mobilise states and peoples. Military aggression in the name of former empires and defence in the name of democracy are a reminder of history’s shadow and the moral force of modernisation, which shapes modern Asia as clearly as it does modern Europe.

But there is a key lesson that distinguishes Taiwan’s circumstances from Ukraine’s that is at once prosaic and consequential: international representation matters.

As a state in the international system seeking support for its defence, Ukraine has benefited from a host of international organisations: the UN, both the Security Council and the General Assembly; NATO and the EU; and numerous individual states, including Australia. Ukraine’s charismatic president, Volodymyr Zelensky, has addressed parliaments around the world and met with European leaders as the elected president of a sovereign nation with a UN seat and the instruments of diplomatic relations.

The international response in support of Ukraine is an expression of the functioning of the international system itself. Despite the many depredations against it over many decades, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is an assault on that system and the belief that, for all its faults, it remains the best way of organising the affairs of nations.

But unlike Ukraine, Taiwan is largely excluded from the international system. It has diplomatic relations with only 14 countries and no seat at the United Nations. It has membership of some key multilateral trade organisations, including the World Trade Organization and APEC, as ‘Chinese Taipei’, not Taiwan, but no state-to-state security alliances or defence treaties.

By its very existence as a sovereign, democratic state standing outside the international system, Taiwan expresses the system’s failure to properly account for occluded histories and its willingness to compromise state power and economic opportunity with the national sovereignty upon which it depends.

But, in practice, Taiwan’s place outside the international system means that in the event of military action by China, the system cannot rally in support in the name of its own integrity. There will be no powerful speeches in defence of Taiwan’s sovereignty at the UN, like that offered by Kenya for Ukraine, that are implicitly a defence of the international order itself.

Instead, any support for Taiwan around the world will be improvised. It will be reliant on the United States, Taiwan’s longstanding supporter, and probably Japan, and their capacity to exercise global leverage. But without recognised statehood for Taiwan, a cross-strait crisis falls into being seen as simply as a contest between great powers, undermining the principles of the international system rather than validating them.

Neither will Taiwan benefit from unequivocal popular political support around the world, despite its achievements as the most progressive democracy in Asia being threatened by an authoritarian state.

When the international system is projected onto domestic politics, it is mapped onto a moral terrain of metaphor and symbolism. For Taiwan, its place outside the international system is read morally, as a place that, for significant political constituencies, is not worth, or is even unworthy of, political support. Disparaging Taiwan’s identity or simply ignoring it are expressions of this domestic moral representation of Taiwan’s international marginality.

Unlike Ukraine, whose existence as a state is a given despite being at war with a nuclear-armed power, the Taiwanese are tasked with arguing from the most foundational principles of democratic sovereignty and self-determination why Taiwan should exist at all.

As a result, despite Taiwan providing a compelling democratic story from which many countries should learn and making a vital contribution to the global economy, the kind of political rallying and popular sentiment that has benefited Ukraine in the domestic politics of many nations will be divided and equivocal for Taiwan.

The key lesson, then, from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is sobering for Taiwan.

In Australia, it points to the need for policies that support Taiwan’s international representation. Even within Australia’s existing policy architecture, this can include actively promoting Taiwan’s membership of multilateral trade and economic groupings, with the goal of conceptualising the kind of international coalition that could support Taiwan in a crisis. It includes setting aside the current passive approach to cultural and education links and actively prompting Australian public institutions, and the university sector in particular, to set aside their reflexive antipathy to Taiwan and to develop partnerships.

But any steps require a clear-eyed understanding in Australia of the failures of the international system to account for Taiwan’s de facto sovereignty and a recognition that the region will not return to a new equilibrium if China annexes Taiwan. Australian policy is premised on equivocation on the status of Taiwan, which Beijing has always sought to leverage, and this remains part of Taiwan’s security calculus.

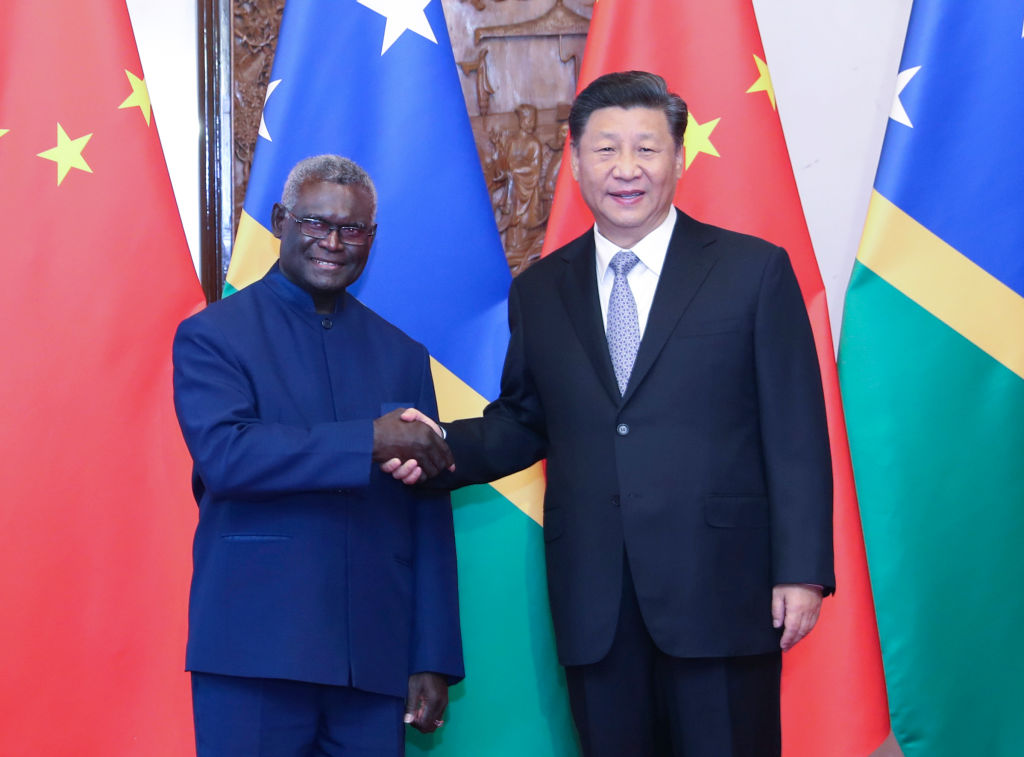

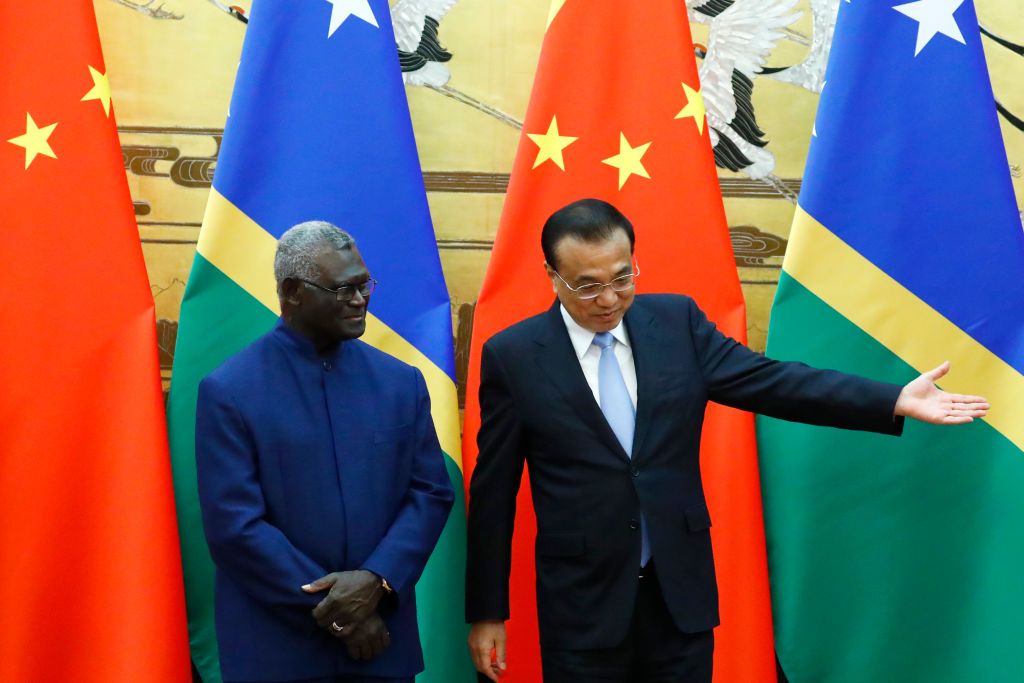

In his statement to the Solomon Islands parliament on the draft security agreement between his country and Beijing, Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare stridently but disingenuously denied ‘pitching into any geopolitical power struggle’.

Despite the shared fears of Sogavare’s domestic critics—one of whom leaked a copy of the draft—and knowing that virtually all of its Western friends profoundly disagreed, the Solomon Islands government has now inked the agreement.

It’s not clear if the signed version is different in any important aspect from the leaked version, but even a significant sanitising of the language wouldn’t undo the damage this event has done to both signatory countries.

In a three-page letter to Sogavare, the president of the Federated States of Micronesia, David Panuelo, set out very clearly the reasons why Solomons security ties with China would pitch the region into the broader geopolitical power struggle.

The letter is particularly significant because it was written from the perspective of the only one of the three Micronesian entities in a freely associated relationship with the US to recognise the People’s Republic of China. (The other two are Marshall Islands and Palau.)

Panuelo argues that, while the Solomons enjoys agency as an independent state to pursue its national interest, it has an obligation to its people, to the region and even to global security to use its agency with prudence. Sogavare has an obligation to recognise that his decisions have consequences for others in the region.

The language and substance of the draft agreement betray its origins in Beijing and thus serve to identify China’s ambitions in the Solomons and by extension the region more generally.

The implied preferential extraterritoriality in the draft allowing China to use its military ‘to protect the safety of Chinese personnel and major projects’ raises concerns beyond Solomons Islands.

The safety of Chinese personnel and their property has been a legitimate concern at several critical points in the Solomons’ history—most notably during the riots in April 2006 and November 2021. Nevertheless, privileging the protection of major Chinese projects goes beyond such events and has an ominous ring regionally.

The Sogavare government signed on to China’s Belt and Road Initiative in 2019 within days of switching recognition from Taipei to Beijing. The association of direct protection by the People’s Liberation Army of BRI projects regionally would be an even more damaging trope for China than ‘debt-trap diplomacy’.

This is not an impossible stretch. Observers have noted that a feature of Chinese contributions to UN peacekeeping missions has been a bias towards protecting China’s commercial assets.

On 31 March, the Australian Defence Force’s joint operations chief, Lieutenant General Greg Bilton, spoke publicly of the consequences of a Chinese military presence on ADF operations. While Bilton was careful to use the language of conditionality, the security agreement has already thrown an enormous rock into the Pacific pond and the ripples will affect all members of the free and open Indo-Pacific project.

The references in the draft agreement to military personnel, armed forces and ship visits with stopover and transition arrangements give rise to justifiable concerns that it will legitimise prepositioning of Chinese military stores as a precursor to a secure naval precinct on its way to a full-blown military base under the pretext of protecting Chinese interests.

The immediate-term objective for Beijing, apparently shared and supported by Sogavare, has been to achieve some parity with Canberra’s security treaty with Honiara signed after the Australian-led Regional Assistance Mission to Solomons Islands ended. A long-term objective in light of last year’s AUKUS announcement may be to focus Australia’s security concerns closer to home and away from the South China Sea.

A belated public declaration that the Solomons would never allow a Chinese military base is scarcely likely to settle concerns.

The Sogavare government’s dissembling and lack of transparency on the switch in recognition to Beijing, the secrecy provisions in the draft agreement and the smuggling of replica military-grade Chinese weapons to the Solomons for police training have intensified the trust issues regarding Chinese ambitions.

Even where local opinion minimises the likelihood of any intended military objectives in or through Solomon Islands, the security agreement is recognised as troubling at the domestic level.

The privileged protection of major Chinese projects is laden with risk, particularly with regard to inflaming interethnic rivalries and possibly leading to outright conflict.

There are serious tensions between the government of the Solomons’ largest province, Malaita, and the Sogavare government. Malaita Premier Daniel Suidani has vowed to never allow Chinese money into Malaita.

The continuing resistance of the province to accepting Chinese aid projects is a source of annoyance to Honiara. The use of Chinese police or military personnel to protect a major development project forced on Malaita would very likely reignite the deadly civil conflict of two decades ago.

Another potential flashpoint is also on the horizon. Opposition leader Matthew Wale has warned that there may be a constitutional crisis looming as Sogavare appears to want to extend the life of his government by postponing national elections due next year until 2024.

Acknowledging the media reports of this proposal, Governor-General David Vunagi warned that it would require constitutional change approved by parliament.

Although some constitutional provisions require a three-quarters vote, it appears that this change might need only two-thirds of the parliament. If that’s true, judging by the no-confidence vote Sogavare survived in December 2021, the numbers could be there for such a change.

A serious constitutional crisis where a third of the population strongly resent an attempt to extend the life of the Sogavare government could reignite interethnic conflict, which is why Australian troops are currently on Guadalcanal.

Just how far would Beijing go to protect a government that has delivered so much to China? Equally, how far would Canberra go to defend the democratic values required under the Biketawa Declaration if a competent authority such as the governor-general made the request?

One thing is certain: the regional security egg has been scrambled. There’s no way back to the sense of manageable balance that existed before the leaking of the draft agreement.

Whatever financial advantage the Sogavare government thinks its leveraging of sovereignty has won for it, the precautionary cost in the security response of states unable to trust the Solomons’ promises is likely to be much higher.

News that a draft security agreement between Solomon Islands and China may soon be formalised has raised concerns in Canberra that Beijing could use it to establish a military base on Australia’s northern doorstep.

If the agreement is approved by the Solomon Islands parliament, it could eventually allow China to establish a strategically placed military and paramilitary presence in the Pacific islands.

ASPI’s Michael Shoebridge notes that the key paragraph of the leaked draft agreement states that:

China may, according to its own needs and with the consent of the Solomon Islands, make ship visits to, carry out logistical replenishment in, and have stopover and transition in the Solomon Islands, and the relevant forces of China can be used to protect the safety of Chinese personnel and major projects in the Solomon Islands.

It appears that under the agreement China would have the right to deploy PLA Navy and Chinese Coast Guard vessels to Solomon Islands and have them replenished by Chinese forces stationed there. Those forces could also be used to protect Chinese major projects in the Solomons. This implies a permanent military or para-military presence requiring regular support from China. That could come via PLA Air Force cargo aircraft and PLA Navy vessels, and would require a logistics capability ashore and personnel to operate the port and manage air operations. That would be a significant presence, so how should Australia respond?

There’s a case for a two-track approach combining diplomacy and dialogue, alongside prudent defence planning. International security scholars Joanne Wallis and Anna Powles make a strong case that Australia has a path forward through dialogue and diplomacy.

The goal would be to ensure that the draft agreement isn’t passed through the Solomons parliament in the first place. Recognising that the legitimate security concerns of South Pacific states are different to Australia’s will require the next Australian government take the Pacific step-up to a new level.

ASPI’s Peter Jennings makes a convincing case for a more comprehensive approach to Pacific island security that is proactive rather than reactive. That would demand that Australia does more to address issues of concern to those states, such as climate change, in a meaningful way and more urgently, even as China shows indifference to this vital issue. It’s important that Australia step up to a higher level of statesmanship and really address the issues that challenge these much smaller nations.

It’s prudent to recognise that the agreement with China may be indeed be passed by the Solomons parliament. Expect China to then move swiftly to establish a forward military presence.

From Honiara to Brisbane is a little over 2,000 kilometres and, as Jennings notes, would be an ideal location for gathering signals intelligence and establishing an over-the-horizon radar system to monitor naval activity. It would also make sense for China to exploit deep waters offshore to lay undersea sonar arrays to monitor Australian, US and UK submarine activity out of Australia’s mooted east-coast nuclear submarine base.

From a forward military presence in Honiara, China would be better able to exert influence on other pacific island states, including Vanuatu, where it has already built a deep-water wharf in Espiritu Santo. A foothold in Honiara could allow China much greater presence and broader influence across the region.

In a time of conflict, a Chinese base in Solomon Islands could threaten sea lanes and open up Australia’s east coast to direct military threat for the first time since the end of World War II.

If such a facility is built, the case for strengthening Australian surveillance in the southwest Pacific would be very clear. The planned extension of the Jindalee Operational Radar Network is a first step that is already underway, but a more resilient approach to maritime surveillance into the Southwest Pacific would be needed in case of conflict. That could include both an expansion and an acceleration of space-based intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance to incorporate ocean-surveillance satellites and provide an ability to track incoming cruise missiles, including hypersonic ones.

Greater maritime patrol and response capabilities, incorporating the P-8A Poseidon and the yet-to-be-delivered MQ-4C Triton and MQ-9B SkyGuardian drones, to monitor any Chinese naval operations in the southwest Pacific, would also be important.

Responding to an emerging threat to Australia’s eastern seaboard would demand a rethink of the Australian Defence Force’s overall posture. Whichever government is in power after the May election should pursue reviews of both defence capability and force posture, in ways that build on both the 2020 defence strategic update and 2020 force structure plan, as well as the AUKUS agreement. Our strategic environment is changing rapidly, so policy and capability acquisition must keep pace.

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s endgame in Ukraine remains unclear. But his war there does seem to be sending one clear message: if you have nukes, nobody messes with you. The security risks this poses cannot be overestimated.

Just days after launching his invasion of Ukraine, Putin announced that he had placed Russia’s nuclear forces on ‘high alert’—a clear warning to the West not to intervene militarily on Ukraine’s behalf. And it seems to have worked. Despite Russia’s relentless bombardment, including of civilian areas, the United States has flatly refused Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s repeated requests for a NATO-enforced no-fly zone.

The reason is simple: The West fears the consequences of all-out war with a nuclear-armed power. While this is not unreasonable, it is likely to erode trust in America’s nuclear umbrella, the effectiveness of which, as a 2020 study showed, was declining long before Russia began its war against Ukraine. The only way a country can credibly protect itself from attack by a nuclear power, it now seems clear, is to maintain nuclear weapons of its own.

For Ukraine, this is particularly frustrating. In 1994, after the end of the Cold War, the country surrendered its nuclear arsenal—then the world’s third largest—in exchange for security assurances that turned out to be meaningless. Not surprisingly, some officials have indicated that they regret disarmament.

Likewise, the Ukraine war has vindicated those countries that were already pursuing nuclear weapons, and they have redoubled their commitment to doing so. In recent weeks, North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un has conducted several high-profile missile tests, including a failed test of a new intercontinental ballistic missile.

But the nuclear power to watch in Asia is China. Since it tested its first nuclear device in 1964, China has adhered to a doctrine of minimum deterrence—essentially, maintaining just enough nuclear weapons to be able to retaliate against a nuclear attack. That is about 350 warheads today, compared to America’s 5,550 and Russia’s 6,000.

So, while China has long possessed a nuclear deterrent, it has avoided wasting hundreds of billions of dollars building a large arsenal—an effort that probably would have triggered a regional nuclear-arms race. There are of course limits to this approach. In a conflict with another nuclear power, China could be neutralised with a pre-emptive strike and missile defence. But a war between nuclear-armed powers seemed so unlikely that maintaining minimum deterrence seemed like a good bet.

The deepening cold war with the US changed China’s strategic calculations. Last December, the US Department of Defense estimated that China was seeking to double its nuclear stockpile by 2027 and amass 1,000 warheads by 2030.

Following the Ukraine war, China will surely strengthen these efforts. It certainly has the resources for a massive arms buildup. And, with Putin issuing nuclear threats and tensions over Taiwan intensifying, the strategic imperative is stronger than ever.

But the nuclear buildup will not stop with China. Several of Asia’s key players are now set to be dragged into a costly and dangerous arms race that will make the entire region less secure. India, China’s regional rival, will seek to expand its own arsenal, prompting India’s nuclear-armed nemesis, Pakistan, to do the same.

This would place East Asia’s non-nuclear states, such as Japan and South Korea, in a quandary. Already, former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe has called for Japan to consider hosting American nuclear weapons. Though the current prime minister, Fumio Kishida, quickly rejected the idea, the proposal represents a major shift in a country that has abided by the principles of nuclear non-proliferation since World War II.

If an Asian nuclear-arms race takes hold, countries’ willingness to challenge taboos will only increase. In both Japan and South Korea, nuclear weapons will become the most divisive domestic political issue, with national-security hawks advocating their development, even if doing so jeopardises relations with the US, which views nuclear proliferation as an existential threat.

Finally, Taiwan might decide to acquire nuclear weapons as insurance against a Chinese invasion. But this would almost certainly precipitate just such an invasion. The resulting conflict, which could well involve the US, could quickly escalate into a nuclear war.

The world has long depended on the principle of mutual assured destruction to prevent nuclear war. But, even if MAD deters countries from launching premeditated wars, it cannot protect against accidents or miscalculations. The more nuclear weapons the world has, and the more fearful countries are that their adversaries will launch pre-emptive strikes, the more acute the risks become.

By bolstering the case for more nuclear weapons in Asia, Putin’s war in Ukraine could decimate what little is left of the region’s strategic stability. This not only poses an existential threat to Asia; it would also deliver yet another blow to the global non-proliferation regime, making it even harder to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons in other regions.

Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare has a Chinese-government-proposed text for a security agreement between his country and China, which is apparently being considered by his government.

The draft agreement leaked to the media is a short, broad document with some specifics about a process for the Solomons to request Chinese police, armed police and People’s Liberation Army assistance to deal with unrest. That’s a disturbing picture, given the authoritarian nature of Chinese enforcement functions like the oddly named People’s Armed Police and the brutal work we’ve seen the Chinese police, paramilitary and military do on the streets of Hong Kong, in Xinjiang and in Tiananmen Square.

But the bigger issue for every person in every one of the 18 member nations of the Pacific Islands Forum is the other bit of the draft agreement, which says:

China may, according to its own needs and with the consent of the Solomon Islands, make ship visits to, carry out logistical replenishment in, and have stopover and transition in Solomon Islands, and the relevant forces of China can be used to protect the safety of Chinese personnel and major projects in the Solomon Islands.

That’s a very broad, loose set of permissions for Xi Jinping to use his forces to operate in and from Solomon Islands. And it’s straight from the Beijing playbook: create new forms of activity and then normalise and increase them in accordance with Chinese interests.

A core issue is that South Pacific leaders have been hoping that strategic competition wouldn’t come to them in any way other than a contest to give them things. And we’ve had statements from leaders like former Vanuatuan foreign minister Ralph Regenvanu showing this sentiment: Chinese interest is good for us because it means we get better offers from our other partners.

Like Australians until the Huawei 5G decision back in 2018 and some business figures even now, some have been happy to take Chinese cash and downplay the downsides, particularly if they’re longer term and the benefits are more immediate.

But the prospect of a routine Chinese navy and army presence in Solomon Islands shows that this transactionally savvy approach to get better deals is coming to an end, and the nasty end of direct military and strategic competition—tension and perhaps even conflict—is coming in the form of Chinese power, which will no doubt be opposed by Australia and its allies and partners in the South Pacific.

Australia’s task now is to support those who already see these implications—like Solomon Islands opposition leader Matthew Wale and other figures across the Pacific, along with voices in Honiara calling for greater honesty and openness in government like Reginald Ngati.

It also means shifting the views of those who still think the possibility of a standing PLA military presence in the region is scaremongering by Australia or others. I’m certain plenty of voices in the Solomons and other Pacific states understand this, even if particular leaders like Sogavare know but don’t care because of other priorities (in an echo of Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews on the Belt and Road Initiative saying he wasn’t responsible for national security or foreign policy, just jobs in his state).

Would a new treaty signed by Pacific states committing to no such military presence by China or other authoritarian powers help? Probably not. The Pacific Islands Forum’s Boe Declaration already commits to a region of ‘peace, harmony, security, social inclusion and prosperity so that all Pacific people can lead free, healthy and productive lives’ and rejects foreign interference. Providing a place for China’s military to project power from inside the region would certainly clash with these principles.

And as we know with space and cyber treaties, the simple fact is that two kinds of states sign these agreements: ones that do what they sign up to—like the Pacific Islands Forum states and partners like the UK, US, France and New Zealand—and those, like Russia, China and North Korea, that sign hoping others feel bound while happily breaking any obligations themselves, just as Xi did when he tore up his obligations under the Sino-UK treaty on Hong Kong with his brutal crackdown in 2019.

It’s understandable for South Pacific governments, businesses and people to welcome economic and even political competition, including from China. However, the draft agreement’s clause on ship replenishment and logistics support ‘according to China’s needs’ would bring a very different type of competition—real military competition—into the heart of the South Pacific.

It is not in the interests of South Pacific peoples to have the region become a place of military competition, tension and conflict. Even if some leaders don’t want to act on this, other voices should be listened to. And Australia’s job is to speak frankly and keep our word, to show that we are part of the Pacific family and are as deeply against our region becoming a place of actual military tension as any of our Pacific partners are.

Let’s think through events like the targeting with a military-grade laser of an Australian P-8A Poseidon aircraft by a PLA Navy guided-missile destroyer on its way to Tonga just weeks ago. This type of event would become routine behaviour and interaction in the South Pacific.

The single biggest factor that can either bring this reality into being or prevent it is whether the Chinese military is given permission by any government in our region to establish places to base and operate from.

The bad news is that China’s economic leverage can make it hard for a small state to refuse. Australia has had a hard time shifting from our decades-long, wilfully blind dash for Chinese cash, and has only done so grudgingly in recent years as the security implications of an aggressive China under Xi became too obvious to ignore.

The good news here is that, short of a war like Vladimir Putin’s in Ukraine, China can’t unilaterally impose a standing military presence in our region. Such a move would require an active choice by one of our Pacific partners—a choice any government should make not in isolation but by listening to its own people and to every other member of the Pacific family.

If, after careful consideration of all angles around this draft agreement, Sogavare’s government decides not to invite an authoritarian state to establish an armed presence in Solomon Islands, we should remain alert but not alarmed.

Beijing’s goals, set out in numerous speeches by Xi Jinping and in decisions and actions, are clear now. Number one remains Xi and the Chinese Communist Party staying in power indefinitely as rulers of China’s 1.4 billion people—Xi’s real ‘China dream’.

Xi and his acolytes want three big things:

These priorities interact with the deep partnership that has developed between Moscow and Beijing, starting with the 2001 Treaty of Good-Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation, accelerating under the growing relationship between Xi and Vladimir Putin since 2013 and culminating in their joint statement less than three weeks before Putin launched his long-foreshadowed invasion of Ukraine on 24 February.

Looked at with these priorities and this context in mind, Putin’s war in Ukraine, like Covid-19 and increased strategic competition with the US and other major powers, has negative and positive consequences for the rulers in Beijing.

On the negative side, Putin’s war exposes the contradictions in Chinese policy and action. Beijing’s long espousal of the principles of non-interference in other states and respect for their sovereignty looks meaningless when placed against Xi’s and the broader Chinese government’s clear diplomatic protection for Putin as he engages in an aggressive war that directly breaches them.

Xi’s vague and conflicting language, repeated by China’s foreign ministry and various state media mouthpieces, attempts to blur and blunt the jarring contradiction at the heart of Beijing’s position on the war. But his words are entirely unconvincing, as many of the Chinese state voices engaged in this effort may well realise.

Here’s the foreign ministry’s readout of Xi talking to Germany’s Olaf Scholz and France’s Emmanuel Macron:

President Xi stressed that the current situation in Ukraine is worrisome, and the Chinese side is deeply grieved by the outbreak of war again on the European continent. China maintains that the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries must be respected, the purposes and principles of the UN Charter must be fully observed, the legitimate security concerns of all countries must be taken seriously …

So, the ‘current situation’ is ‘worrisome’, as if the war were some naturally occurring phenomenon troubling Europe rather than the result of human decision-making—in this case by someone Xi knows well: Vladimir Putin.

While wrapping himself in a lofty reference to the UN charter, Xi ensures he supports Putin’s stated reason for starting this war and killing so many Ukrainian civilians and Russian and Ukrainian soldiers. Xi tells Macron and Scholz that ‘the legitimate security concerns of all countries must be taken seriously’. He knows this phrasing is an echo of Russia’s language on the conflict, as we’ve heard from figures like Putin, Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and Deputy Foreign Minister Alexander Grushko. He also knows there’s nothing legitimate about Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, a state China has recognised since 1992 and a UN member since 1991.

Putin’s war is also forcing Chinese companies and financial institutions to adopt the West’s broad, deep sanctions against Russian entities because, if they fail to comply, they risk losing much larger international markets than Russia.

There’s tension, no doubt, between these corporate decisions and the government’s opposition to the sanctions—characterising those adopted by the EU, the G7, every NATO member and numerous other countries from Switzerland to Australia as ‘unilateral’, despite the word’s mathematically implausibility in these circumstances.

But that tension may not be terribly pronounced or long-lasting: Xi’s reassertion of CCP control over state-owned enterprises and all Chinese companies means they’ll subordinate their commercial interests to state interests and policy directions.

Beijing clearly wants to find ways to continue to trade with and support Russia economically and financially while Putin wages war. Foreign Minister Wang Yi has asserted that because China is ‘not a party to the conflict’, it shouldn’t have to adopt sanctions or comply with them. Chinese officials have gone further, saying China hopes to maintain normal trade with Russia while Putin is in the midst of his war.

This means we should expect the Chinese government’s policy for itself and for China’s corporate and financial actors to be to do the minimum required to be narrowly technically compliant with international sanctions while creatively engineering ways to provide Russia with economic and financial support.

While Chinese companies and institutions with international markets well beyond Russia are complying for now, the sanctions are giving Beijing’s policymakers an opportunity to learn how broad, deep sanctions might be developed as a policy tool for their government. This will inform Beijing’s work on its own sanctions machinery to use against others.

Like its position on state sovereignty and non-interference, we should expect the purity of Beijing’s position against ‘unilateral’ sanctions to not trouble Chinese officials at all when it comes to employing their own sanctions as weapons to complement their informal, truly unilateral economic coercion methods.

And the unified sanctions against Russia are a forceful catalyst to accelerate implementation of Beijing’s own economic and technological strategy of dual circulation, aimed at reducing China’s dependence on US- and EU-led financial markets, supply chains and technology, with a particular focus on digital technologies. This was already a core matter for Xi and his CCP politburo colleagues because of the growing strategic and technological competition between China, the US and, increasingly, the EU.

But the shock of seeing previously divided countries and powers across Europe and the Indo-Pacific act with such speed and unity of purpose against Russia will inject urgency into Chinese action. So, we’ll see an acceleration of the technological ‘decoupling’ of China from the larger democratic world, and a broadening of that decoupling beyond the technology sector, with energy and even renewables being likely new areas.

That decoupling will become turbo-charged should Beijing provide not only economic, financial and diplomatic support to Putin but also material military assistance to his war.

US intelligence has revealed that Moscow has already asked Beijing for such assistance—apparently including supplies like armed drones. And the information was sufficiently reliable for US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan to raise the issue directly with CCP politburo member Yang Jiechi in an inconclusive seven-hour meeting in Rome.

Beijing—and Xi himself—are likely to have absolutely no intention of shifting from their partnership with and support for Putin, but they will work covertly and in ways that allow them to claim they’re not in technical breach of sanctions but are ‘seeking peace’. Beijing will continue to bet that the attraction of its large market and the passage of time will reduce other governments’ unity on Russia, and make it easier for Beijing to walk its preferred path.

But Beijing’s decision-making and calculations have proven far less supple and successful, and more strident and inwardly focused, as the Xi era wears on, so it’s unlikely to be able to strike this balance in the sea of contradictions it finds itself in. To paraphrase that seasoned politician of the 1970s and 1980s, Joh Bjelke-Petersen, ‘You can’t sit on the fence and keep your ear to the ground without terrible things happening.’ The prospects of Beijing being exposed for deep, active support to Putin are growing.

The consequences will be a further shattering of what’s left of the ‘global economy’ and the beginning of a world challenged by the manifest strategic partnership between the twin autocracies of Russia and China. This challenge, unexpectedly, is likely to be met with much greater unity and will than we had any right to expect before 24 February.

As the United States slides deeper into a proxy war with Russia, Indo-Pacific countries are increasingly concerned about the long-term implications of the Ukraine crisis for America’s power and position in this part of the world.

And so they should be. While President Joe Biden’s initial approach to Ukraine struck the right balance of resolve and restraint—marshalling global allies in support of sanctions against Russia and funnelling military and humanitarian aid to Ukraine—the war is now sapping more and more American attention and defence resources.

A dangerous tit for tat is taking hold. Washington’s lethal military aid and economy-breaking sanctions signal an investment in the war that could slip beyond Biden’s original articulation of limited interests. Russia’s nuclear threats and increasingly brutal operations have triggered further US involvement, including the deployment of advanced F-35 fighters and expensive Patriot missile-defence systems to NATO frontlines in Eastern Europe, and a massive US$13.6 billion Ukraine emergency bill passed by Congress last week. Calls are getting louder for a ‘limited no-fly zone’ which, though rebuffed so far, may become politically harder to resist.

All this is understandable given the humanitarian carnage. But hot on the heels of the release of Biden’s Indo-Pacific strategy, it’s unsettling to watch Washington’s strategic gaze drift, once again, away from a robust ‘pivot to Asia’.

As we argue in a new United States Studies Centre report, these developments are especially worrying given that the Biden administration has so far failed to deliver on key defence components of its regional strategy.

Senior US officials insist that events in Europe will not see the Indo-Pacific or efforts to balance Chinese power deprioritised. Earlier this month, the White House’s Indo-Pacific coordinator, Kurt Campbell, again promised that Washington was capable of sustaining ‘deep commitments’ in both theatres simultaneously, even at great cost, just as it had in the past.

But while America can—and must—continue to buttress European security, it doesn’t enjoy the luxury of riches or unchallenged military primacy required to underwrite an expansive global strategy against two great-power rivals.

Matching ends with means in the Indo-Pacific—America’s so-called ‘priority theatre’—requires difficult trade-offs between competing priorities, including in Ukraine. A more sustainable division of US and allied defence responsibilities in Europe and Asia is urgently required.

Biden understands this and deserves credit for attempting to match US global interests and commitments in his first year. Poor execution aside, his Afghan withdrawal showed a willingness to make tough, politically unpopular trade-offs. His initially restrained approach to the Ukraine crisis suggested he would keep it in global strategic perspective.

But Washington won’t be able to sideline Moscow from its foreign policy agenda the way it had hoped. Delays to the publication of the US national defence strategy and national security strategy suggest that Russia is forcing a hurried reassessment of Biden’s global priorities. In a worst-case scenario for the Indo-Pacific, it’s possible these documents will return US military strategy to an equally weighted focus on Asia and Europe—contradicting hard-fought efforts in recent years to make China the Pentagon’s outright priority.

This is not a callous point to make. America simply doesn’t have the military resources required to prosecute an effective multi-theatre strategy in an era of great-power rivalry. Nor is it spending enough to change this equation: while the 2018 national defence strategy recommended 3% to 5% real growth in defence spending annually to keep pace with China and Russia, not a single defence budget since has met these targets.

Biden’s budget continues this unsatisfactory trend. And in contrast to the stark warnings from top brass at US Indo-Pacific Command, who see conflict with China as a possibility this decade, the administration’s defence budget prioritises long-term military modernisation in anticipation of high-end conflict in the 2030s—leaving the US underprepared to deal with Chinese military coercion over the next few years.

Budget shortfalls are mirrored by slow-moving efforts to realign US forces globally. While Canberra and Washington have agreed to new posture arrangements for US forces to undertake expanded training, sustainment and military operations from Australian soil, the administration’s global posture review offered little else for the region. By contrast, it put on hold further Middle East drawdowns and made no significant cuts to troop numbers in Europe, which have since risen as a result of the war in Ukraine.

Even the Pentagon’s new Pacific deterrence initiative falls short of the mark in the quantum of investment in forward military posture, logistics, air defences, and fuel and munitions stockpiles.

There is nevertheless a silver lining for allies like Australia: the Biden administration appears highly responsive to our ideas when it comes to regional defence initiatives.

The unprecedented AUKUS defence industrial partnership is the clearest win for Australia on this front, offering rare access to nuclear-powered submarine technology and deeper industrial and technology integration—a result of sustained Australian lobbying in Washington.

Other allies have benefited too. Japan secured more extensive collaboration with the US on cutting-edge defence technologies and South Korea is reaping the rewards of decades-long efforts to lift US restrictions on its ballistic missile technology.

These efforts to empower US allies are even more important as Washington is once again pulled in conflicting global directions. Indo-Pacific allies should advocate for more. As a priority, Australia should caucus with Japan and other close security partners to push for overdue reforms to US export controls on defence technology. Realising the full promise of AUKUS, establishing a sovereign guided weapons and explosive ordnance enterprise to build high-end missiles in this country, and achieving Australia’s full integration into the US national technology and industrial base all depend on such revisions.

Indo-Pacific allies should also press Washington for greater insight and input into its regional military planning. A credible collective defence strategy requires clarity on when, where and how to address shared defence challenges. Biden’s effort to build support among regional allies for a Taiwan contingency is a step in this direction. But while Taiwan is the Pentagon’s ‘pacing challenge’, regional countries face Chinese military coercion across a far wider range of lower intensity scenarios, as China’s intimidation of an Australian military aircraft in the Arafura Sea last month attests. New strategic planning initiatives must reflect these realities.

In the end, however, these initiatives can’t change the strategic physics of the Indo-Pacific. A favourable balance of power with China can only be upheld with unprecedented US support. Alliance modernisation is a necessary component of this strategy, but it’s not a substitute for a robust US military posture and presence in the Indo-Pacific.

As the conflict in Ukraine grinds on, America’s capacity to deliver an effective defence strategy for the region will depend on its ability to keep its escalating involvement in check and in global strategic perspective.