Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Beijing’s creation of a new state-owned company to centralise China’s purchases of iron ore and other metal resources is unlikely to have much impact while markets are tight and prices are high, but it could become a weapon against Australia in the event of an iron ore glut.

The China Iron and Steel Association (CISA), which is the government-sanctioned body representing China’s major steel companies, has long railed against what it sees as an iron ore producers’ cartel and pushed for a central buying agency to counter it.

The four biggest suppliers of seaborne iron ore—Rio Tinto, BHP, Fortescue Metals and Brazil’s Vale—account for about 70% of world trade and about 80% of China’s imports.

China’s nationalist English-language daily, the Global Times, said the goal was ‘to create a centrally administered state giant to have a bigger say in ore pricing by leveraging China’s strength as the world’s largest consumer of iron ore’.

The new China Mineral Resources Group, launched last month, has been granted significant start-up capital of ¥20 billion ($4.2 billion) and has a high-powered leadership team. Its chair is Yao Lin, outgoing chair of Aluminum Corporation of China, or Chinalco, and its operations are headed by Guo Bin, former vice president of the world’s biggest steelmaker, China Baowu Steel.

BHP has responded sceptically to the new venture. Chief Financial Officer David Lamont noted that China’s previous efforts to negotiate iron ore prices with a single voice hadn’t been successful.

‘Let me say up front, at the end of the day we believe that markets will sort out where the price needs to be based on supply and demand,’ he told a business forum in Melbourne.

‘So we’re not worried about that. It’s something that’s been talked about for a period of time.’

Asked directly whether he thought the new venture would succeed, he responded, ‘History would say no.’

That’s a reference to the efforts of CISA in 2009 to mount a boycott of the biggest three miners—BHP, Rio Tinto and Vale—as it sought to impose an 82% cut to the iron ore price. The boycott was ultimately broken, first by small mills seeking to secure their supplies, and then by the majors.

The head of CISA was forced out and BHP succeeded in persuading the Chinese steel industry to accept long-term contracts based on the spot price index, rather than hammered out in annual bilateral negotiations.

China has a vast steel industry with about 250 large steel mills and thousands of small ones. Both CISA and successive governments have sought to consolidate the industry but with limited success. Some large mergers have raised the output share of the top 10 steel mills from 36% to 43% over the past two years, but that still leaves a highly fragmented industry.

While China has been attempting to shut down its smallest and least efficient mills, the country continues to build new ones. Tracking by a think tank based in Finland established that 18 new blast furnaces with a capacity of 35 million tonnes (about seven times Australia’s output) were approved in just the first half of 2021.

Blast furnaces are critically dependent on a constant supply of iron ore and coal and face massive restart costs if they’re forced to suspend operations. The problem with central buying is that smaller mills will fear that the interests of the largest mills will receive preference, and that their survival will be jeopardised if supplies are interrupted.

The push for centralised buying has been a response to high prices. The iron ore price reached a record US$240 a tonne in May 2021, delivering spectacular profits to the biggest miners, whose production costs at the time were less than US$15 a tonne. Although the price has come down a long way, it’s still at an enormously profitable level of around US$100 a tonne.

Central buying is likely to be most effective when prices are depressed. If a glut of iron ore emerged, smaller Chinese mills would have less concern about supply security and would have an incentive to join the central agency if they believed it could deliver lower prices.

China’s vast steel industry will always need Australian iron ore, but a central agency could decide to favour non-Australian supplies.

The Japanese steel cartel that operated from the 1960s through to the 1990s was seen to have engineered surplus supplies and was able to keep the iron ore price at levels delivering bare profitability to the miners. The iron ore price hovered between US$11 a tonne and US$14 a tonne throughout the 1990s.

Although China’s steel industry doesn’t resemble the Japanese steel cartel, the history of bulk commodities is that they deliver flat returns, like utilities. The only reason they’ve been so profitable for the past 20 years is the explosion in China’s demand, which has no parallel in history.

China’s new resource company has also been given responsibility for increasing its supply, including the development of the large Simandou iron ore project in Guinea. The new Guinean government, which took power in a coup last year, has given the project operators until 2025 to start production. Formidable technical and political challenges remain, but the probability of the project’s being realised has increased.

However, the greater risk for Australia is not increased supply but a fall in Chinese demand. That may be happening now. China’s steel production was down 6.5% in the first half of the year, and stocks are growing.

The conventional wisdom is that a softening in the Chinese economy is bullish for iron ore because the government responds with steel-intensive infrastructure construction. Infrastructure spending is indeed rising, but its share of steel demand at around 20% to 25% is below that of the property sector at 35% to 40% and real-estate investment is in a slump.

It is beyond the scope of this article to consider the broad forces at work in the Chinese economy, but a serious recession is possible, given the challenges of high debts, falling property prices, weak income growth and rising world interest rates, which are also threatening a global downturn.

The China boom has been spectacular for Australia. A key economic measure is the terms of trade, which is the ratio of export prices to import prices and is measured as an index.

For 50 years from the mid-1950s, that was fairly constant at around 60, but in 2005, it started rising as China’s demand for resources accelerated and the cost of Australia’s manufactured imports fell. By September 2011, it reached an unprecedented 120, meaning that every tonne of Australian exports was buying twice as many imports as was the case six years earlier or throughout most of Australia’s history.

While that sounds abstract, a return to the long-run average for the terms of trade could wipe out $250 billion of national annual income, with big implications for both government finances and Australian living standards. The China Mineral Resources Group could help make that happen.

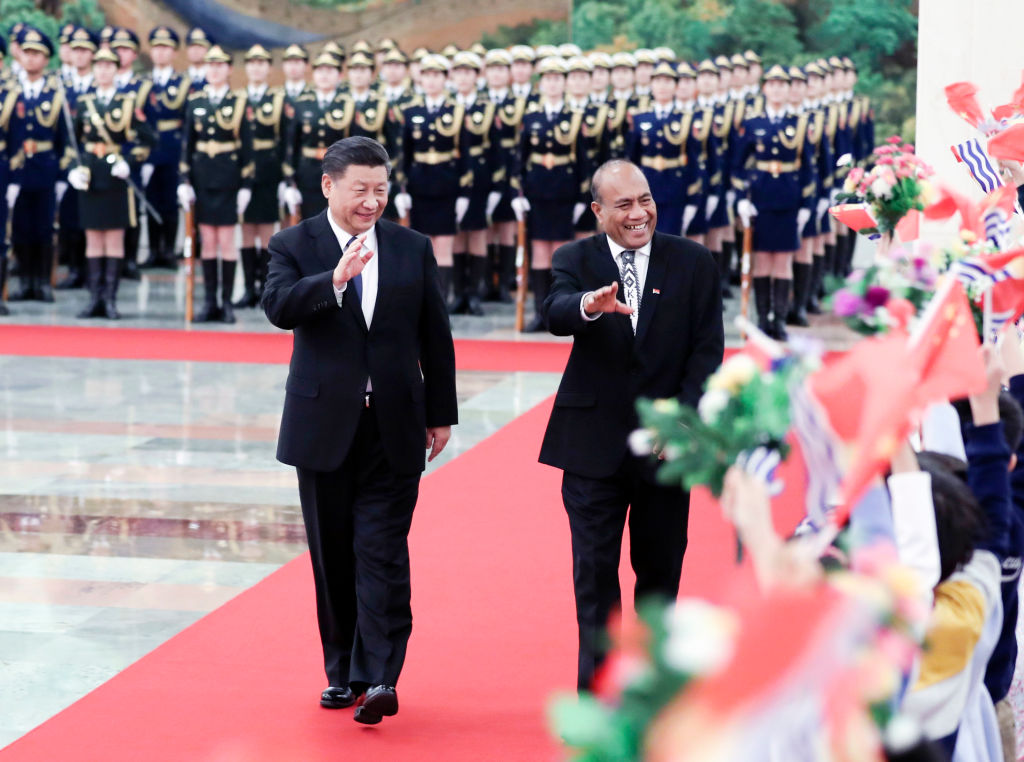

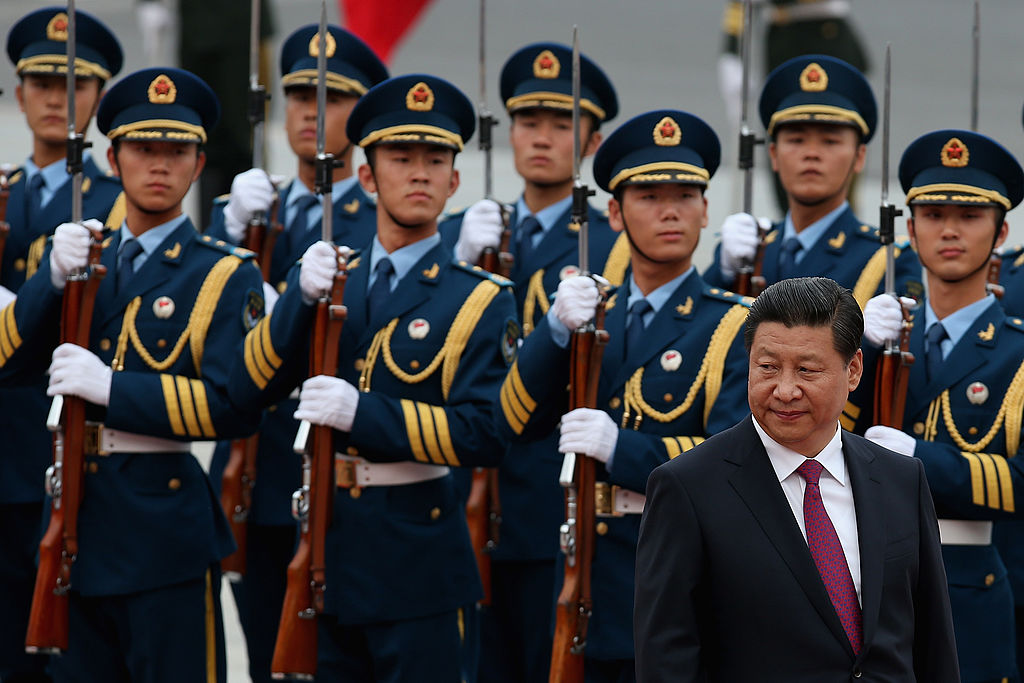

When Indonesian President Joko Widodo visits his country’s three major North Asian economic partners this week, bilateral trade and investment, along with the upcoming G20 leaders’ summit in Bali, are set to head his list of priorities. But whether he likes it or not, they are unlikely to be the only topics on the minds of his principal interlocutors, especially China’s President Xi Jinping.

Widodo’s first stop (26 July) is Beijing, where he will meet both Xi and Premier Li Keqiang. Generally, the leaders will have a good story to highlight during what will be Widodo’s fifth visit to China. Despite an array of international and domestic complications, the value of bilateral trade totalled US$110 billion last year, confirming China’s status as Indonesia’s largest trading partner. Imports from China amounted to five times the value of US exports to Indonesia. During the January–April period this year, Indonesia enjoyed a trade surplus of just over US$1 billion arising from the more than US$44 billion in trade.

China has also consolidated its position in the top three foreign investors in Indonesia (after Singapore and Hong Kong), contributing to a 39.7% year-on-year jump in foreign direct investment in Indonesia’s economy during the second quarter—the biggest rise in a decade. In the first six months of 2022, China accounted for US$1.7 billion of the total of US$15.65 billion in foreign direct investment into Indonesia.

Most of that investment flowed into key sectors in the Indonesian economy, including mining and the metals industry, transportation, telecommunications and utilities. China has been especially active in many of these, notably the expanding smelting industry, in which Chinese companies are becoming dominant actors.

A key deliverable (as foreshadowed by Indonesia’s all-powerful coordinating minister for maritime affairs and investment, Luhut Pandjaitan) is likely to be the renewal of a 2017 memorandum of understanding underpinning Indonesia’s participation in China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which is scheduled to end this month.

But not everything in the economic relationship is rosy. The troubled Jakarta–Bandung high-speed rail project is bound to be a key part of the conversation. A totem of Indonesia’s development cooperation with China (if not an officially acknowledged BRI project), it is being undertaken by a consortium of Indonesian state-owned enterprises and Chinese companies. Under the original arrangement, the China Development Bank was to finance 75% of the project.

But it has been bedevilled by construction problems that have resulted in lengthy delays and a multibillion-dollar cost blowout necessitating an unanticipated, controversial injection of government funding from a reluctant administration. This reportedly prompted Indonesia last year to press China to help defray the rising costs.

Indonesian authorities continue to insist that the project will be completed in time for a trial run to coincide with the November G20 meeting. That would serve the interests of both leaders, showcasing Indonesia’s development achievements and China’s claims as a beneficent and technologically impressive partner. But experience to date and the Indonesian consortium members’ financial problems offer ample grounds for doubt that the trial train will run on time. To help ensure it does, therefore, Widodo’s cap may again be in his hand as it reaches out to shake Xi’s.

Widodo will also doubtless be expecting Beijing’s unbridled support for Indonesia’s G20 presidency and its agenda of post-Covid-19 global economic recovery and resilience. A specific initiative for which Widodo may be seeking Xi’s formal backing is the establishment of a financial intermediary fund to aid in ‘health management under the management of the World Bank’, as Indonesia’s finance minister, Sri Mulyani Indrawati, has outlined. He’s likely to get it, as well as a ringing endorsement for his goal of keeping the G20 as focused on Indonesia’s economic cooperation agenda as the war in Ukraine and the reaction of G7 countries to it will allow.

It’s just as certain that Xi will want a few things in return. One may well be some kind of endorsement of China’s condemnation of AUKUS, specifically in terms of Australia’s planned acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines. Jakarta’s concerns about this issue haven’t been so forcefully expressed as Beijing’s strident remarks, and Widodo is likely to be careful not to align Indonesia too overtly with whatever actions China might be planning to take against Australia in the context of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, including at next month’s 10th NPT Review Conference. But Beijing would know that Jakarta’s scepticism towards the submarine program almost certainly persists regardless of the Albanese government’s efforts to reassure its Indonesian counterpart and will likely be aiming to stoke it.

From an Australian perspective, then, the visit underscores the importance of Canberra’s cooperation with its AUKUS partners and the International Atomic Energy Agency towards an answer to the NPT questions posed by AUKUS that will prove acceptable to Indonesia and other sceptics in the region. Hopefully, as he departs from Beijing, Widodo might also reflect on the fact that the same person urging him to condemn Australia’s ambitions for nuclear-propelled—not nuclear-armed—boats is concurrently overseeing the growth of China’s nuclear arsenal contrary to its obligations under the NPT to disarm—an obligation that Indonesia has consistently demanded that nuclear-weapon states meet.

The Tokyo (27 July) and Seoul (28 July) legs of Widodo’s trip are set to be no less heavily centred on economic matters, and especially on spruiking for more foreign direct investment. Widodo is scheduled to hold meetings with business communities in both capitals as well as with his counterparts, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol. Both countries sit among the top six investors in Indonesia, though it won’t have escaped Widodo’s attention that Japan, hitherto among the top two or three providers of foreign direct investment to Indonesia, has fallen to sixth spot in 2022, below the Netherlands and South Korea.

Defence cooperation, however, may well also be an item on the leaders’ meetings in both capitals. Seoul in particular will be interested in where Indonesia is heading on its defence procurement plans in light of the two countries’ cooperation on the KFX fighter program and Jakarta’s apparent deal to procure 42 Rafale fighters from France. It will be especially interested to glean whether Indonesia remains committed to the program and, post-Covid, is ready and able to meet its financial commitments under it.

Both Japan and Korea have also figured in Indonesia’s ambitions to enhance its naval and maritime domain awareness capabilities. Seoul has already provided three new submarines (one of which was assembled in Surabaya) and, earlier this year, the first of several second-hand corvettes that Jakarta hopes to secure.

Indonesia, however, has in the past given both nations reason to question its reliability as a defence partner. Widodo may well have his work cut out when it comes to shifting any such perception.

Beijing is moving at high speed to co-opt South Pacific states economically and then use that leverage to achieve broader goals, including the ability to project military power across the Indo-Pacific. China is also working to undercut Pacific regionalism and obtain advantage from its bilateral engagement with individual Pacific states, with obvious successes in Solomon Islands, while Manasseh Sogavare remains prime minister, and now with Kiribati.

The swiftness of Beijing’s actions is obscured by both the pandemic and the focus of policymakers and analysts on the global implications of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine. It would be nice to be able to take comfort in the obvious personal priority that Australia’s new government, notably Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Foreign Minister Penny Wong, is putting on engagement with the South Pacific, but developments in the region and between China and individual Pacific states create doubt about what can be achieved from the face-to-face diplomacy and the policy approaches outlined so far.

Australia and like-minded partners are moving to enhance their cooperation with Pacific states. However, it seems likely that China’s economic and cash-based engagement will continue exploiting a large seam that our engagement is leaving largely unaddressed.

That’s because we continue to prioritise decades-long approaches focused on aid, capacity-building and defence cooperation, now with the additional, welcome, priority of cooperation on climate change action. These priorities respond to stated needs of Pacific states, but they will probably do little to change the region’s status as the most aid-dependent area on the planet.

And aid-dependent small states are inherently vulnerable to the economic largesse of the Chinese state and its closely aligned corporate actors—banks and companies. We’re seeing this pattern in Kiribati’s engagement with China and, even more obviously with Sogavare’s embrace of Beijing and simultaneous distancing from Australia.

Australia, the US, New Zealand, Japan and Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) members and dialogue partners seek to support the forum’s vision of regionalism because of the values inherent in ‘a common sense of identity and purpose, leading progressively to the sharing of institutions, resources, and markets’.

But there’s an important other aspect to effective regional cooperation, which is for the PIF to act as a shield for the region to resist Chinese co-option that will undercut the security of Pacific states—and of Australia and New Zealand.

Effective regionalism benefits each Pacific state and the whole region. Splintering of regionalism benefits China and allows it to use the same methods of interaction that are damaging in other regions. Europe is the most obvious example.

Beijing has a track record of forming its own Sino-centred forums for engagement and avoiding working closely with multilateral and regional groupings. This allows it to use its weight and scale with individual nations in direct interaction and to avoid confronting the combined weight that regional bodies like the EU or the PIF can bring to bear.

The underlying behaviour of Chinese Communist Party officials and leaders is captured by the infamously frank statement of China’s then foreign minister Yang Jiechi in 2010 when, faced with differences between Southeast Asian states and China, he told ASEAN representatives: ‘China is a big country and other countries are small countries, and that’s just a fact.’ February’s joint statement by Xi Jinping and Putin just weeks before Putin began his war in Europe is a reminder that this way of thinking and operating—where scale and raw power are used to determine outcomes, not respect for sovereignty of nations large and small—is how Xi is pushing his party and individuals like China’s current foreign minister Wang Yi to operate.

In 2012, European states welcomed China’s 16+1 forum, officially called the Cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries, as a way of collaborating economically, seeing it as complementary to EU activities and simply about obtaining direct benefits without the interface of the EU. When Greece joined in 2019, after pushing its role in Xi’s signature Belt and Road Initiative, the grouping expanded to 17 European states engaging with Beijing (the 17+1 forum).

Since then, things have changed. Most obviously, Lithuania withdrew in 2021, calling on others to do the same. Lithuania’s foreign minister, Gabrielius Landsbergis, said: ‘From our perspective, it is high time for the EU to move from a dividing 16+1 format to a more uniting and therefore much more efficient 27+1. The EU is strongest when all 27 member states act together along with EU institutions.’ There’s a direct lesson in this for Pacific states, which smaller European states with histories of dealing with the two big autocratic powers in Moscow and Beijing can help Pacific states to learn without the painful, belated discoveries happening in Europe.

The idea that the EU is strongest when all EU states act together through EU institutions is obviously true—perhaps even more true—for the Pacific. The PIF magnifies the weight and influence of each member state and gives the region more agency and authority when dealing with even the largest powers. This sense of common purpose has been obvious in how PIF members have worked to change international policies on climate change, for example. They have achieved much more together than each could have done alone. Arguably, the strong Pacific voices on this issue helped enable the Australian policy change we are now witnessing.

The PIF leaders and their democratically aligned dialogue partners must bring this same cohesion and sense of common purpose to bear in dealing with the uncomfortable truth that, right now, the South Pacific is a key place on the map that Beijing has identified as providing real, rapid opportunities to achieve long-desired strategic gains.

So far, though, on China the Pacific is moving in the opposite direction to Central Europe. Just this week, Kiribati’s government announced that it’s leaving the PIF while signalling a growing appetite to engage directly with Beijing. For all the denials of anything other than benign and normal international relations, this centres on expanding China’s ability to project military power unconstrained by US and allied power.

The Pacific is again a central place for active and direct strategic competition, and denying that or pretending otherwise will only advantage Beijing and leave Pacific states—and their people—victims of insecurity and tension.

Dealing with this must be the role and responsibility of the Pacific states themselves, but Australia and its partners must acknowledge that our current policies will continue to fail to reverse the momentum of Beijing’s moves in the region.

For Australia, this starts with not rewarding China’s government for simply meeting with Australian counterparts by agreeing to ‘shelve differences’ as Beijing acts against our strategic and national security interests in the South China Sea, in its partnership with Moscow and now in direct security moves in our near region.

Our differences with Beijing are stark and growing—as other governments and organisations are also now finding—and focusing only on the positives is a path to disarray and disadvantage.

China is not making the gains it is with Sogavare, and now with Kiribati’s president Taneti Maamau, because of its positive work with the Pacific on climate change. It’s making its strategic gains from economic engagement—and cash splashes for elites who help achieve Beijing’s goals. Beijing is also rewarding those who act against regional interests and pursue short-term transactional and political benefit.

Without a much larger, more ambitious strategy for the South Pacific that has an economic and workforce focus and marks a radical shift from our decades of failed capacity-building and aid, we will be bystanders as Beijing’s direct reach and presence grow. Cutting aid is obviously a bad idea, but that doesn’t mean that simply expanding aid is the path to success.

The good news is that the real advantage Australia and New Zealand have is economic. The working model for what a prosperous and stable region looks like can be found in the wildly successful Australia – New Zealand Closer Economic Relations framework and visa-free travel for work. This opens economies and employment markets between Australia and New Zealand and, if extended to small Pacific states, would turn aid-dependent places into joint contributors to successful economic regionalism, addressing the needs of South Pacific workers for meaningful employment while simultaneously filling growing workforce gaps in Australia’s economy.

Another advantage Australia and its partners have in the South Pacific is the fact that we’re democracies and so can engage not just with counterpart governments, but with democratic opposition figures and voices and non-government institutions, and at people-to-people levels. This will also require a shift in government thinking in Canberra to make meetings with opposition figures—like Matthew Wale in Solomon Islands and Tessie Lambourne in Kiribati—a normal part of relations. Engaging beyond the government of the day is routine in other relationships, like the Australia–UK partnership and the Australia–US alliance, for example.

As the realisation dawns on the new Australian government, and on the governments and institutions in Tokyo, Washington, Paris and Brussels, that opening embassies, expanding aid programs, having greater ambition on climate change and doing small-scale but valuable work on ocean management and illegal fishing isn’t reversing China’s strategic momentum, things will have to change.

Australia and New Zealand, working closely with partners, must move towards a bigger way of thinking and acting centred on economics and democracy. And, as we see with the splintering of the PIF and bilateral moves from Beijing with small-state leaders, time is not our friend.

Beijing will be keeping a close watch on the G7’s efforts to cap the price of Russian oil because China is trying to do the same to Australian iron ore.

As the world’s biggest exporter of resources and energy, Australia has a vital interest in transparent and freely negotiated commodity markets. Its economy would be seriously jeopardised if consumers were successful in using their combined power to supress prices for specific commodities.

China accounts for 70% of global imports of iron ore and has long believed that its dominance of the market should give it greater influence over prices. The China Iron and Steel Association plans to have a central iron ore buying agency in place by the end of the year to stop individual steel mills from bidding up prices against each other.

The G7 plan would exploit the US’s and UK’s control of financial services to the shipping industry, particularly insurance, to prevent Russian oil from being loaded on tankers if its price exceeded a G7-imposed limit. Although the G7 accounts for only 30% of global oil imports, virtually all shipping insurance goes through the London markets.

Insurers would be forbidden from providing coverage for ships taking on Russian oil at higher prices. Two-thirds of Russian oil is shipped in tankers owned by companies based in the European Union, the UK or Norway, which increases the G7’s leverage.

The idea is that the price cap on Russian oil would apply not only to the oil purchases of G7 nations but to all Russian oil exports.

The G7 ambition is to stop Russia from profiteering from the energy crisis that has been partly precipitated by its war on Ukraine. ‘We are working to make sure Russia does not exploit its position as an energy producer to profit from its aggression at the expense of vulnerable countries,’ the G7 communiqué said.

The volume of Russia’s oil, gas and coal exports in the first three months of the war was down 15% from the same time last year, reflecting the impact of sanctions, but the average revenue is up by 60%, even after taking into account the discounts that Russian oil is suffering in world markets, according to analysis from a Finnish think tank.

Russian oil has been selling at about a 30% discount to the Brent benchmark (based on the price for North Sea oils) to compensate for the difficulty in obtaining trade finance for dealing with Russia.

Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida indicated that a much steeper discount was envisaged in the G7 plan, commenting that the price cap would be ‘about half’ the current market price of around US$100 a barrel.

The big risk in the G7 plan is that rather than accept the imposition of a 50% price cut by Russia’s adversaries, Russian President Vladimir Putin would order a halt to the country’s oil exports to anyone demanding sub-market prices.

Russia accounts for around 8% of oil supplies to the global market. Its former president Dmitry Medvedev recently warned that the G7 plan could take global prices well above US$300 to US$400 a barrel.

That is hyperbole, but former International Monetary Fund chief economist Olivier Blanchard has estimated that the removal of just 3% of world oil supplies could result in a 30% price increase.

There would also be a risk that other big consumers of Russian oil like China and India would arrange their own insurance and shipping to keep their Russian oil flowing. The more oil Russia could sell outside the G7 blockade, the easier it would be for it to cut sales to the West.

The defining feature of commodities is their fungibility—they are the same wherever they are produced and, as a result, they fetch the same price, barring market interference.

Oil is the world’s biggest commodity market, with annual international trade of about US$1 trillion, or about four times the size of next-ranked iron ore. With vast numbers of sellers and buyers, it would be difficult to hermetically seal Russia’s 8% market share.

Even against the relatively small producers Iran and Venezuela, former US president Donald Trump’s ‘maximum pressure’ campaign of sanctions had only partial success. Oil sales were reduced but not eliminated because work-arounds were developed.

The idea of a G7 price cap was first mooted by US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen in February. Last month’s G7 summit agreed to ‘explore’ the concept; however, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz commented afterwards that the concept was ‘very ambitious’ and would ‘need a lot of work’ to become a reality.

The danger is that a buyers’ cartel would prove no more effective than the OPEC producers’ cartel was in the 1970s. While OPEC engineered a short-lived price spike, within a decade its share of the world oil market had dropped from 51% to 30%.

One might imagine that fixing the price of iron ore would be a lot simpler in China’s centrally planned and authoritarian economy. Yet, a concerted effort to impose a buyers’ cartel failed in 2009. When price negotiations became deadlocked, the China Iron and Steel Association ordered a complete boycott of Australian iron ore. However, smaller mills—fearful for the security of their supply—ignored the order, which ultimately led to the collapse of negotiated iron ore prices.

A recent Australian Financial Review report, which appeared to reflect the thinking of the iron ore majors, commented that rumours of a central buying group had been around for a decade without coming to anything. One of the problems is that China has hundreds of steel mills. Small mills would be concerned that a central buying group would favour the large state-owned steel mills.

China’s demand for steel is volatile, depending on political decisions on infrastructure and other stimulus programs, as well as on the vagaries of the property sector. Central planners frequently get their forecasts of demand wrong, so both large and small mills would be left sweating on the accuracy of the central buying group’s orders.

All consumers want lower prices, but it’s ultimately the genius of transparent markets that they deliver a price that matches both supply and demand. The suppression of a price through consumer power (known as ‘monopsony’) ultimately leads to lower investment, lower production and higher prices. In the same way, the artificial boosting of a price through a producer monopoly would lead to a search for substitutes and a long-lasting destruction of demand.

The chances of either the G7 engineering a special discounted price for Russian oil or China manipulating the price of Australian iron ore are not high. However, with resources and energy accounting for almost two-thirds of Australia’s exports, the new resources minister, Madeleine King, should be paying close attention to their efforts.

In September 2020, at the conclusion of a UK parliamentary committee hearing during which TikTok executives were grilled, in public, for the first time, committee member Kevin Brennan offered his colleagues a frank assessment of how he thought the questioning went.

‘At the end of the session I got the distinct feeling that the committee, talented as we all are, had failed to land a single blow on the witness,’ he admitted. Brennan, the MP for Cardiff West, clearly couldn’t get rid of a niggling suspicion that he and his colleagues had missed something fundamental.

Brennan’s intuition was right—something very fundamental had been missed, but not for want of trying. His colleague Damian Green asked TikTok executive Theo Bertram, a former adviser to UK prime ministers Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, more than once, in a manner of words, if TikTok user data was being sent back to China, but Bertram, the experienced political operator, had equivocated.

‘I have explained several times that we have systems in place to protect our users’ data from access from overseas, in China specifically,’ Bertram told the committee before answering a question that had not actually been asked of him: ‘No employee in China can access TikTok data in the way that you are suggesting on behalf of the CCP [Chinese Communist Party] to carry out mass surveillance. That is not possible.’

Two days later, at an Australian parliamentary committee hearing, TikTok executives were at pains to minimise the extent to which TikTok was in any way connected to China, let alone reveal whether its users’ data was being accessed from there. Their talking points—that TikTok user data was stored in Singapore and the United States and that the company would never hand over the data to the Chinese government even if it were asked—were beside the point.

The location in which any data is stored is immaterial if it can be readily accessed from China. Moreover, TikTok’s parent company, ByteDance, couldn’t realistically refuse a request from the Chinese government for TikTok user data because a suite of national security laws effectively compels individuals and companies to participate in Chinese ‘intelligence work’. If the authorities requested TikTok user data, the company would be required by law to assist the government and then would be legally prevented from speaking publicly about the matter.

In the two years since these parliamentary inquiries, TikTok executives have continued to duck and weave, including in an appearance before the US Congress. In October last year, TikTok vice president and former Republican congressional aide Michael Beckerman parried back and forth for seven minutes with Republican Senator Ted Cruz, desperately trying to avoid answering a simple question about whether TikTok user data, based on the platform’s privacy policy, can go back to an affiliate based in the People’s Republic of China.

‘You have dodged the questions more than any witness I have seen in my nine years serving in the Senate,’ Cruz said to Beckerman. ‘In my experience, when a witness does that, it is because they are hiding something.’

The politicos-turned-TikTok-executives have been savvy enough to avoid a made-for-TV moment when they admit that their users’ data is being accessed from China. But, as I and my ASPI colleagues made clear in our 2020 report on the app, they have never completely denied that that’s the case.

Specifically, a 2020 blog post from TikTok Chief Security Officer Roland Cloutier stated that it was TikTok’s goal for China-based employees to have minimal access to user data. In other words, not only was TikTok user data being accessed in China, but it wasn’t even the company’s intention at the time to completely cut off that access.

In an under-reported September 2020 sworn affidavit, Cloutier was even more explicit. ‘TikTok relies on China-based ByteDance personnel for certain engineering functions that require them to access encrypted TikTok user data,’ he admitted. ‘According to our Data Access Approval Process, these China-based employees may access these encrypted data elements in decrypted form based on demonstrated need and only if they receive permission from our US-based team.’

Last month, a bombshell report from BuzzFeed, based on leaked audio from more than 80 internal TikTok meetings, blew away any pretence that user data was being properly protected by TikTok’s ‘world-renowned, US-based security team’. Instead, as one member of TikTok’s trust and safety department put it in a September 2021 meeting, ‘Everything is seen in China’. In another meeting that month, a director referred to one Beijing-based engineer as a ‘master admin’ who ‘has access to everything’.

When asked about the report by a group of nine Republican senators, TikTok CEO Shou Zi Chew finally acknowledged that China-based employees ‘can have access to TikTok US user data’ and outlined a plan dubbed ‘Project Texas’ that the company had hastily announced in an effort to counteract BuzzFeed’s exposé.

Despite this newfound transparency, this week, Brent Thomas, a former Labor candidate for the seat of Hughes and now TikTok Australia’s director of public policy, continued the kabuki theatre. In his own 900-word response to a letter from Shadow Cybersecurity Minister James Paterson in which he and TikTok Australia CEO Lee Hunter were asked if Australian TikTok users’ data was also accessible in China, Thomas vacillated.

In answering Paterson’s straightforward question, Thomas gave a convoluted answer that drew heavily on previous, vaguely worded statements made by Cloutier, but curiously failed to cite his 2020 affidavit that plainly states that TikTok user data is being accessed by the company’s China-based employees. Only an extremely close reading of the letter reveals that TikTok did not deny what has now become painfully obvious.

At some stage—and hopefully soon—politicians will bring in legislation to properly protect Australians’ privacy and data from all of the big tech companies, whether they’re from the US or China. In the meantime, TikTok Australia needs to be straight with its users so they can make up their own minds.

The recent virtual BRICS summit, which brought together the heads of state and government of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, was interesting as much for what didn’t happen as for what did. The two-day gathering was marked by some constructive discussion but also platitudes and pablum, and concluded with a grandly titled but thoroughly anodyne ‘Beijing declaration’.

Few doubt the huge potential of the BRICS, which comprises the world’s two most populous countries (China and India), a former superpower (Russia) and two of the biggest economies in South America and Africa. But the grouping’s record since the first annual BRIC meeting in 2009 (South Africa joined the bloc the following year) has mostly been a story of lofty rhetoric and chronic underachievement.

The Beijing declaration states that the BRICS high-level dialogue is an opportunity to deepen cooperation in the fight against Covid-19, digital transformation, supply-chain resilience and stability, and low-carbon development. All these goals are being pursued in a variety of multilateral forums.

More hypocritically, the declaration condemned terrorism and called for the finalisation and adoption of the Comprehensive Convention on International Terrorism within the United Nations framework. This rang rather hollow, since the summit took place just days after China blocked a joint proposal by India and the United States to designate the Pakistan-based Abdul Rehman Makki as an international terrorist under the provisions of the UN Sanctions Committee.

This wasn’t the first time that China stymied a proposal for the sanctions committee to list known Pakistan-based terrorists. It has repeatedly blocked efforts to designate as international terrorists Masood Azhar, chief of the UN-proscribed terrorist entity Jaish-e-Mohammed, and others associated with the equally murderous Lashkar-e-Taiba. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi pointedly stated at the BRICS summit that the group’s members should understand each other’s security concerns and provide mutual support in the designation of terrorists, adding that this sensitive issue should not be ‘politicised’.

It was against this background that China, the summit chair, floated a proposal to enlarge the group by accepting new members, and subsequent reports claimed that Argentina and Iran had applied to join. But the matter was not officially discussed at the meeting and featured only tentatively in the closing declaration.

Underlying the enlargement issue are two questions that go to the heart of the BRICS grouping. First, is it primarily an economic organisation or a geopolitical one? Second, if the BRICS is largely a geopolitical bloc, will it become the principal vehicle for the emergence of a global axis led by China and Russia—a goal that China appears to support and that the proposed enlargement, and the putative candidates, seems intended to serve? In that case, what is India doing in it?

As to the first question, the BRIC acronym—created by Goldman Sachs economist Jim O’Neill in 2001—was initially impelled by a vision of economic cooperation. The four (later five) emerging markets’ shared and compatible perspectives on issues of global governance reform certainly provided a raison d’être.

But their common concerns about the direction of global development and the power of the Western-dominated Bretton Woods institutions meant that the group’s agenda was political as well. The BRICS seemed to be emerging as the premier platform of the ‘global south’, articulating developing countries’ dissent from the so-called Washington consensus—a tendency underscored by the addition of South Africa, the only African economy in the G20.

In recent years, however, the global environment has changed dramatically. A backlash against globalisation and a US–China trade war, as well as heightened suspicions among US policymakers of China’s geopolitical intentions, have been compounded by military hostilities between China and India, including the killing of 20 Indian soldiers along the countries’ disputed Himalayan border in 2020.

As a result, the BRICS appears to be undergoing an identity crisis. Indian foreign policy mandarins initially saw the group as a useful platform to increase India’s international influence, in keeping with its traditional role as a leader of the developing world. But India is plainly uneasy about efforts to turn the bloc into a geopolitical forum supporting Chinese and Russian interests—and to enlarge it to include other ‘like-minded’ states such as Iran. (Brazil has also maintained a studied silence on Argentina’s reported membership application.)

India is said to have had a crucial hand in the drafting of the Beijing declaration’s single reference to the bloc’s enlargement, buried deep within the 75-paragraph document. Paragraph 73 states: ‘We support promoting discussions among BRICS members on [the] BRICS expansion process. We stress the need to clarify the guiding principles, standards, criteria and procedures for this expansion process through [the] Sherpas’ channel on the basis of full consultation and consensus.’

Humphrey Appleby, the famously circumlocutory British bureaucrat in the Yes, Minister television series, couldn’t have put it better, except perhaps for adding ‘in the fullness of time’. The meaning is clear: ‘full consultation’ is a recipe for indefinite delay, and the insistence on ‘consensus’ means that at least one state will ensure that enlargement never happens.

It appears that China hasn’t taken India fully into its confidence regarding BRICS expansion plans and the pending applications. India can scarcely be expected to welcome an enlargement of the BRICS that’s intended to make the bloc more China-centric. There are also the inevitable concerns about whether, given China’s patronage, Pakistan would be next in line to join.

India has always been the indispensable swing vowel in the BRICS acronym. If the bloc’s current strategic direction and possible enlargement push the country towards the exit, the grouping will become not just unpronounceable, but also unviable.

If norms exist in the Chinese Communist Party, perhaps Xi Jinping, the general secretary and de facto president of the People’s Republic of China, has established one by attending the inauguration of incoming chief executives. He last came to Hong Kong five years ago when Carrie Lam took up the post.

But his visit, whose length did not match the three days of 2017, perhaps from a fear of Covid-19 or a need to concentrate on mitigating its economic and social consequences on the mainland, has deeper significance.

For Xi himself, it is an opportunity to bang the nationalist and patriotic drums in this important year when he intends to continue for a third term in the trinity of top party, army and state posts. This reminder to the Chinese people that the CCP ended the ‘century of foreign humiliation’, which began with the ceding of Hong Kong to Britain, portrays Xi as the embodiment of the CCP’s success.

For others, the 25th anniversary is significant as a halfway milestone to 2047. Before the 1997 handover of Hong Kong, Deng Xiaoping, then paramount leader of the PRC, had promised ‘50 years no change’ (五十年不变) as reassurance that his policy of ‘one country, two systems’ would allow Hong Kong’s freedoms to continue and remain different from those on the mainland.

So, where does Hong Kong stand 25 years after the handover?

The answer is not where the people of Hong Kong and the British government hoped back in 1997. At best Hong Kong experiences ‘one country, one and a half systems’. ‘50 years no change’ was always a way of papering over unresolved differences or worries. The hope was that, by 2047, the PRC would have changed, and thus the gap with the Hong Kong system would have narrowed. Indeed the CCP has changed—for the worse—and the gap between past rhetoric and present reality has widened.

Every five years or so since 1997 the clash between Hong Kong’s and Beijing’s interpretation of ‘one country, two systems’ boiled over into protest. The issues were unsurprising: national security legislation (2003); national education (2012); electoral system (2014); and extradition arrangements, which then led to wider unrest (2019).

The wide scale demonstrations and street violence of 2019 convinced the CCP that its three ‘red lines’—no harm to national security, no challenge to the central government’s authority and the ‘basic law’, and no using Hong Kong as a base to undermine the PRC—had been crossed. In essence, they embodied the fear that Hong Kong’s protests and values might spill over into neighbouring Guangdong province and provoke unrest. The spear point of the CCP’s response was the national security law, or NSL, which came into force on 1 July 2020. The NSL centred on four crimes: secession from the PRC, subversion, terrorism and collusion with foreign forces. Their definitions are elastic—intentionally—and their enforcement ubiquitous. Currently, around 150 people are awaiting trial.

While maintaining the slogan of ‘one country, two systems’, the CCP has reached into its traditional playbook for ensuring control. No self-respecting and aspiring totalitarian regime can afford to ignore:

Among other signs of reduced differences between Hong Kong and the mainland, there have been increasing interference and self-censorship in the arts and culture, an expansion of technological surveillance, and a greater presence and powers to operate for mainland security forces.

Hong Kong’s value to the PRC has been steadily diminishing. Its gross domestic product, once equivalent to over 18% of that of the mainland, is now under 3%. Its port and airport, while formidable, are matched by recently built facilities elsewhere in the south of the PRC. Shanghai, Shenzhen and other cities are increasingly important in meeting the PRC’s financial needs.

Yet Hong Kong retains value for Beijing. While the CCP might be happy to see Shanghai and Shenzhen take over the ex-colony’s financial role, there are impediments while the Chinese yuan, unlike the Hong Kong dollar, remains a non-convertible currency (and will for many years). Hong Kong has been a good place for Chinese companies to raise money. And it has proved useful for powerful CCP members as a safer place for their families and capital.

But Deng’s phrase of ‘50 years without change’ still haunts. It implies change after 2047. The CCP has set itself the ‘second centennial goal’ of becoming a ‘strong, democratic, civilised, harmonious and modern socialist country’ by 2049, the centenary of its founding of the PRC. Translated from party-speak, this means that the PRC is to become the world’s primary superpower in an international order transformed to its advantage and values. It is surely inconceivable that a CCP so committed to a narrative of nationalism and superiority would be happy for Hong Kong to retain much more than the merest vestiges of ‘one country, two systems’. For the CCP, Hong Kong must become no different from any other mainland city, including a move away from the common law system to legal consistency with the mainland.

This absorbing of Hong Kong into the mainland is partly what lies behind Xi’s emphasis on the ‘greater bay area’ plan, an intention to mould the 10 major cities of Guangdong province into an unrivalled economic and technological powerhouse. Hong Kong’s identity, population and culture would be subsumed and diluted into insignificance within the 126 million people of the neighbouring province. It is no coincidence that in the 28 June People’s Daily article announcing Xi’s visit, a large portion centres on Hong Kong’s future in the greater bay area. As 2047 looms, the CCP may be indifferent to whether foreign companies stay in Hong Kong or move north: if they wish to do business in the PRC, they will need a presence in Hong Kong or the mainland.

Sometimes it is the smallest details which reveal the state of things. The mainland press has assured the world that the Hong Kong police detachment of honour will no longer march in its traditional British fashion but with a mainland goose step. Political slogans, never a feature in Hong Kong, have been floating on boats through Victoria Harbour. Outside the Hong Kong police headquarters two banners spread different messages. In Chinese, there is the disconcerting message about a threat as yet unseen in Hong Kong, ‘Remember to report terrorists. The next victim could be you’ and in English, ‘United we stand’. One country, two audiences.

Last weekend’s Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore was the first since 2019 because of the Covid-19 pandemic, which seemed to make the event cathartic for pent-up tensions in the international system. Taiwan was a major topic of discussion, even if the Taiwanese government wasn’t formally represented.

US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, China’s Minister for Defence Wei Fenghe and Australia’s new Defence Minister Richard Marles all made references to Taiwan in their speeches and fielded a number of questions about the prospects for conflict.

None of their comments conveyed changed policies on Taiwan, but they were notably categorical in tone. They therefore represented an intervention in Taiwan policy that’s difficult to capture with the norms of foreign policy analysis.

Taiwan’s position as simultaneously excluded from the international system and situated at the centre of US–China relations and global technology supply chains means that layers of international Taiwan policy operate at the level of the tacit, ambiguous and unsaid. In this way, Taiwan destabilises what is ideally a stable relationship between foreign policy language and state power in the international system.

For national leaders to be unequivocal about Taiwan, therefore, is discomfiting because it creates a fixedness to the language with which the international system addresses Taiwan. It demarcates the complex and unstable realities of Taiwan’s status from the stable norms of the international system and ultimately constrains policy choices and Taiwan’s own future within those norms.

From the US side, the defence secretary affirmed the US position on Taiwan through the key statements: the Taiwan Relations Act, the Six Assurances and the three joint communiqués. He also restated the US commitment to its ‘one China’ policy, which deploys a deliberate ambiguity on the US position on Beijing’s territorial claim over Taiwan.

Austin went on to convey the developing belief in Washington that Beijing is reneging on its commitments to the US over Taiwan made since the 1970s by changing the material conditions in the Taiwan Strait through the use of state power. He was referring to the pattern of People’s Liberation Army Air Force flights across the median line in Taiwan’s air defence identification zone that threatens Taiwan and normalises a territorial claim over the strait. This was also the substance of US President Joe Biden’s comments in Tokyo about the potential for US involvement in the defence of Taiwan. He suggested that Beijing wasn’t holding up its side of the bargain made with Washington in the 1970s and 1980s, and so the US could respond accordingly.

But although Austin stated Washington’s position concomitant with its developing view, he also stated with unusual force: ‘The US does not support Taiwan independence.’

That statement would have come as a disappointment to Taipei, not because it is about to ‘declare independence’ but because President Tsai Ing-wen has worked hard to reframe Taiwan’s status beyond this rigid phraseology that constrains how it’s possible to talk about Taiwan’s past and future. As Tsai has stated, Taiwan has no need to ‘declare independence’ because it is already an independent sovereign state, the Republic of China. But the bald statement by Austin unequivocally places Taiwan outside the international system and that leads to the assumption that Taiwan’s only pathway into it is through ‘reunification’ with the People’s Republic of China. This suits Beijing but not the democratic aspirations of the Taiwanese people.

From the PRC side, Wei gave a speech that was notably belligerent and uncompromising in tone but did not indicate any fundamental change in Beijing’s position.

He declared that China would ‘fight to the very end’ to prevent Taiwan splitting from the mainland. He also said, using the scientistic Marxist teleology of the Chinese Communist Party, that ‘reunification’ was inevitable, in accordance with history’s laws, and that Beijing was ‘making every effort with the greatest sincerities to deliver peaceful reunification’. Beijing’s efforts are limited to offering the people of Taiwan a non-negotiable outcome—one country, two systems—with no roadmap to achieve it. In responding to questions, Wei did affirm a no-first-strike defensive doctrine for China’s nuclear arsenal, which matters for those commentators who use the risk of nuclear war to make an argument about Taiwan’s future that denies the Taiwanese the right of self-determination.

Wei did, however, lambast the Tsai’s government for refusing to accept the 1992 Consensus. This is a policy formulation coined in the early 2000s, referencing non-official negotiations between Taipei and Beijing in 1992, that agreed to set aside the question of Taiwan’s sovereignty in order to facilitate trade and governmental links. However, in a style that is typical of Beijing in many areas of policy beyond Taiwan, what was initially a pragmatically vague formulation has been concretised by the party-state system into an obdurate demand to accede to an immutable principle.

His comments, which have been repeated by PRC officials in Australia, highlights the way Beijing’s specific internal ideological fixations and its policy system can intrude counterproductively into its international relations.

For Australia’s part, the new defense minister responded to a media question about a Taiwan Strait crisis by declining to follow his predecessor’s line about preparing for war. Marles said, ‘Australia supports a one-China policy’, distinguishing Australia’s position from Beijing’s ‘one-China principle’. But he also followed Austin’s statement by saying unequivocally that Australia did not support ‘Taiwanese independence’. He went further, however, and said that Australia had ‘good relations with the people of Taiwan’ (that is, not the government of Taiwan) and stated that ‘what we do want to see is that the situation for the people of Taiwan is resolved through peaceful negotiation’. This diverged from the established formulation ‘the peaceful resolution of cross-strait issues’, in which the use of the plural captures the many aspects of the cross-strait relationship, rather than the single situation of the future of Taiwan itself. Beijing has no negotiable position on the future of Taiwan.

Amid these declarative statements, it was perhaps not surprising that that it was Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky who, in an address via video to the Shangri-La Dialogue, responded to a question about Taiwan without naming Taiwan. Instead, he spoke of ‘certain political leaders who are not content with the present level of their ambitions’ and, on smaller countries, urged the international community to ‘not leave them behind at the mercy of another country’. Zelensky returned the question of Taiwan’s sovereignty to the tacit and unsaid and brought forward the liberal principles of the modern international system of shared peace and progress and the dignity of sovereignty, tacitly giving Taiwan a place in such a system.

President Xi Jinping’s ‘China dream’ now extends across the Pacific Ocean, where his foreign minister, Wang Yi, recently completed a Pacific islands tour of sweeping ambition. Set against the backdrop of China’s stagnating economy yet continuing drive for world power, Wang sought to finalise Beijing’s security agreement with Solomon Islands; visited Fiji, Kiribati, Samoa, Tonga, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea and Timor-Leste; and hosted a meeting of Pacific island foreign ministers in Suva. Wang’s plans, however, didn’t all go smoothly. The Chinese Communist Party will, nonetheless, learn from its failed attempt at achieving a multilateral Pacific deal.

Wang proposed that China and the Pacific countries jointly formulate a ‘marine spatial plan’ to develop the so-called blue economy. Beijing is offering more investment through private capital and Chinese enterprise investment in Pacific island countries. China also proposes new security arrangements, including cybersecurity, reflecting Xi’s ‘global security initiative’, entailing Chinese police and other security forces dispatched to work with participating island nations at both bilateral and regional levels.

Wang’s plans includes establishing Confucius Institutes that embed Chinese-language consultants, teachers and volunteers throughout the islands. More than 1,000 Samoans have already studied Chinese at the Confucius Institute at the National University of Samoa. A separate ‘five-year action plan’ includes a Chinese special envoy being appointed to the region, laboratories and hundreds of training opportunities for law enforcement, and high-level forums.

Wang’s proposals to cash-strapped Pacific island nations would give China a larger footprint in the Pacific, challenging the regional forums that currently defend international law and maintain peace and security. These proposals spotlight the security concerns of the region and Indo-Pacific allies including the US, Australia, New Zealand, France and Canada.

What’s prompted Beijing to propose a regionwide economic and security pact with Pacific island nations? And what are the geopolitical consequences of China’s plans for the Pacific? The responses of several countries highlight the implications, and include the US reopening an embassy in Solomon Islands after a 30-year hiatus.

China’s intentions in the Pacific have now been outlined, so it’s clear why the Solomons security agreement met with international concern. The deal, which took years to execute, is connected to Beijing’s campaign to convert Pacific islands from allegiances with Taiwan to the People’s Republic. The cost of converting the Solomons was high, but the investment now appears to have had a strategic payoff with a window to the South Pacific opening for Beijing.

Wang’s tour seized the moment to prise that window further open. Even though he failed to win a consensus from the 10 Pacific nations for his ‘common development vision’, several countries, including Samoa, Kiribati and Niue, signed up for enhanced cooperation in Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative. The Chinese government has also flagged its determination to push on with wide-ranging trade and security agreements with Pacific island nations.

China’s dream of Pacific expansion ratifies several core interests. The agreement with Solomon Islands reportedly allows China to ‘send police, armed police, military personnel and other law enforcement and armed forces’ and provides for ‘stopovers and replenishment of supplies’. These elements suggest the potential establishment of a military base, although both governments deny this will happen.

But similar agreements have already been made with other Pacific island nations that involved their acceding to build dual military–commercial facilities in return for money and assistance. This is precisely what China wants and has been working towards for decades through its foreign-aid program, seeking dual-use development along with regional cyber control.

Indeed, just a few weeks after the Solomons deal was signed, Xi announced plans to set up a domestic legal framework for expanding the Chinese military’s role in other countries, allowing for Chinese armed forces to ‘safeguard China’s national sovereignty, security and development interests’.

Solomon Islands’ vast exclusive economic zone is resource-rich, replete with timber, significant fish stocks and a range of other natural resources both above and beneath the sea. With 1.4 billion people, it’s unsurprising that China is keen to exploit the region, despite claims to the contrary.

Flipping Solomon Islands from its long-term support for Taiwan in 2019 was a diplomatic success for Beijing. It puts pressure on other nearby island nations, especially the few remaining countries in the region that support Taipei.

A related message that has been conveyed internationally is that Washington’s (and Taipei’s) influence in the Pacific is fading while Beijing’s rises. Domestically, China’s state-controlled media has presented this deal as a significant strategic loss to the US and Australia.

A further interest connected to Beijing’s soft-power push into the Pacific is to eventually add to China’s bloc of ‘global south’ votes at the United Nations. Although this strategy may prove unreliable, garnering South Pacific nations’ votes can help China at the UN.

Almost like a jigsaw piece, the Solomon Islands deal fits perfectly into China’s efforts to reframe the world order, piece by piece, by co-opting small states. It’s now clear that China’s ambitions extend very broadly across the Pacific.

Washington responded to the Beijing–Honiara deal by sending a senior delegation led by Kurt Campbell, the National Security Council’s coordinator for the Indo-Pacific, to meet with leaders in Solomon Islands, Fiji and PNG and register the US’s interests and concerns, including the creation of a potential security risk to the wider region.

Indo-Pacific nations including the US and its allies face a concerted assault on the international rules-based order. To assume Beijing’s intentions are benign would be naive at best, even though some challenges are best shared, such as climate-change action and responses to natural disasters. Secretary of State Antony Blinken recently outlined the US approach to China:

We don’t seek to block China from its role as a major power … But we will defend and strengthen the international law, agreements, principles and institutions that maintain peace and security, protect the rights of individuals and sovereign nations, and make it possible for all countries—including the United States and China—to coexist and cooperate … China is the only country with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military and technological power to do it.

As Federated States of Micronesia President David Panuelo warned, Wang’s ‘pre-determined joint communique’ could spark a new ‘cold war’ between China and the West. Poorer countries like the Solomons, Kiribati, PNG, Timor-Leste and other vulnerable Pacific island nations are confronted with solving monumental challenges. Unless Australia and its allies effectively help Pacific islands as respectful, reliable partners, they may well seek alternatives in their search for solutions.

But with the type of assistance proposed by the Chinese regime, the case has been made that there will very likely be serious strings attached and the promise of a sustainable security architecture can quickly be converted to one of authoritarian control. A taste of this was experienced as Wang’s entourage sought to totally control media coverage of the tour, and its sourness was noted locally.

While the CCP will have learned lessons from this grand tour, so too have Pacific island leaders. Renewed US attention and Australia’s new, closer alignment with the needs of Pacific countries will be helpful.

Echoing Russian President Vladimir Putin’s description of his war in Ukraine, China’s Xi Jinping has released a directive that licenses his armed forces to conduct ‘special military operations’.

This involves the People’s Liberation Army using force outside circumstances that other nations would consider as war. The guidance is consistent with Beijing’s recent coastguard law, which allows that well-armed organisation to use lethal force wherever China claims jurisdiction (as it does in the South China Sea despite its claims being comprehensively rejected under international law). It seems likely to apply to the Taiwan Strait if Xi persists in attempting to assert that the strait is Chinese waters, not a key international waterway.

Xi’s new directive has clear implications for the people of Solomon Islands, as it tells the PLA to use force where required to protect Chinese nationals and Chinese projects and investments. Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare’s deal with Beijing talks about this too, so what Xi is now doing with his military will be applied in the ‘security assistance’ that China’s authoritarian forces provide in and around the Solomons. Like with the Sogavare–Beijing pact, Xi has not released the text of his directive, just had it reported in state media.

Chinese Defence Minister Wei Fenghe, who said at last weekend’s Shangri La Dialogue that he wanted a new positive relationship with his Australian counterpart, Richard Marles, will implement Xi’s direction. The result will be in an even more aggressive PLA in the South China Sea, around Taiwan and Japan, and on the India–China border.

What does all this mean for the prospects of a sustained positive ‘reset’ in the bilateral relationship between Australia and China? All bad things.

It looks very likely that the reset has been gazumped by a more outwardly focused, increasingly aggressive PLA that seeks to define its use of force as ‘not war’.

Definitions that deny reality may work in the land of the Chinese Communist Party. But as Putin is experiencing with the international reaction to his ‘special military operation’ in Ukraine, just calling something what it is not doesn’t prove convincing anywhere in which there’s freedom of expression and media that’s not closely supervised and censored.

The Marles–Wei meeting was a positive development because it’s the only ministerial-level contact between the two countries since China began its diplomatic freeze and then its continuing campaign of economic coercion against Australia in 2020.

It’s also a positive that the meeting happened without Australia needing to show major policy change beforehand. China had demanded that Australia change its policy decisions and directions to resume dialogue—notably in Beijing’s list of ‘14 grievances’.

So, what does Beijing want as the price for resuming dialogue?

Beijing may want the warmer tone and senior meetings to make it harder for Australia to oppose China’s growing military presence in the South Pacific, and harder for Marles to end the Chinese port operator’s lease over the strategic Port of Darwin. There’s leverage there because that would give Beijing a pretext to claim Australia had ended the ‘thaw’.

Wei’s continued line in speeches and dialogues is to assert that China’s approach is one of peaceful cooperation and win–win outcomes, and that anyone noticing anything aggressive or negative in Chinese military or broader government behaviour is smearing China, hurting the feelings of the Chinese people, and adopting a destructive Cold War mindset—usually by being a slave to the US.

Wei’s Shangri-La speech takes this position. That creates a credibility gap for him in dialogue with counterparts like Marles because the PLA he directs is not behaving in any way that could be characterised as peaceful cooperation in pursuit of win–win outcomes.

Instead, the PLA’s aggression in international airspace and waterways is growing, to the extent that mid-air collisions and crashes and on-water incidents are becoming likely as China tries to enforce rights it just doesn’t have.

A broad warming of the Australia–China relationship cannot occur while Beijing persists with unilateral economic coercion across several sectors of our economy; while the PLA behaves increasingly dangerously and aggressively in the South China Sea, around Taiwan and near Japan (all places where the Australian military operates along with partners); or while Beijing accelerates its direct military presence in Solomon Islands and potentially in other parts of the South Pacific.

Marles clearly understands this, using his speech at Shangri La to say: ‘What is important is that the exercise of Chinese power exhibits the characteristics necessary for our shared prosperity and security. Respect for agreed rules and norms. Where trade and investment flow based on agreed rules and binding treaty commitments. And where disputes among states are resolved via dialogue, and in accordance with international law.’

So, the new Australian government’s tone may not be the same as its predecessor’s, but the structural policy directions—on security risks in foreign investment (notably from Chinese entities) and the priority on countering foreign interference in Australian politics, countering traditional and cyber espionage, and working with allies and partners to confront the now overt strategic partnership between Russia and China—all mean that the foundations and differences between Australia and China persist. In fact, the differences are growing as Xi leads China down the path he has chosen.

Given Xi’s latest policy directions to the PLA and the growing gap between General Wei’s words and the PLA’s actions even before this, we should expect resumed government-to-government dialogue to be broadly disappointing to Australia.

That’s because Beijing wants us to compromise but intends to make no significant compromises itself. (This is not unusual or particular to the China–Australia relationship. Wei made it clear that for US–China relations to improve, for example, the US had to make positive moves to reset the relationship. That’s a line many of us hear in our dealings with Beijing, and one Beijing’s foreign ministry has already returned to since the Marles–Wei meeting.)

We should expect Beijing to accelerate its plan to have a direct military presence in the South Pacific and to conduct the newly minted ‘special military operations’ Xi envisions there. This will be a sufficiently grave and adverse development for Australia that the already strong public opinion that assesses China under Xi to be a threat to Australia’s security will harden. And in a democracy, that drives policy.

A collision in the South China Sea, on the water or in the air, would have a similar effect—and it would reverberate well beyond the Australia–China bilateral relationship.

With all this, the Albanese government is likely to continue a more positive, more engaged approach to other key partners in our region. That’s good news for bilateral relationships like the growing ones with Japan, South Korea, India and Indonesia, as well as for minilaterals like the Quad and the Australia–US–Japan trilateral, all underpinned by the military advantages Australia, the US and the UK will bring to the region through AUKUS.

These partnerships and the military power and advantages that come from them seem even more needed considering Xi’s latest move with the PLA.

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria