Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

If there was a prize for the most quotable comment on international relations so far in 2022, Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar would be in the running. Responding to criticism of his country’s neutral stance on the Russia–Ukraine war at a security forum in Slovakia in June, Jaishankar said that ‘Europe has to grow out of the mindset that Europe’s problems are the world’s problems, but the world’s problems are not Europe’s problems.’

Like most major crises, the war is shedding stark light on our era, and India’s response to it is particularly illuminating. India’s foreign policy does more than just exemplify how the conflict has intensified deglobalisation trends. It also highlights the paradox inherent in the country’s increasing emphasis on ‘strategic autonomy’ as the world fragments into rival power centres: the United States and its alliance system versus China and its major satellite, Russia. The essence of this paradox is that India’s quest for self-reliance—keeping its distance from the principals of ‘Cold War 2.0’ and seeking advantage from diverse relationships—entails multidimensional international engagement.

For example, European politicians painfully weaning their countries off imported Russian energy have criticised India for buying more Russian oil—after Western sanctions reduced its price by about a third relative to the world market price. Indian purchases of Russian crude increased to 1.1 million barrels per day (mbpd) by late July and now account for more than a fifth of Indian oil consumption, compared to just 2% last year.

The standard official Indian response is that, despite Europe’s extensive sanctions, the continent’s energy trade with Russia still dwarfs India’s. Its purchases of discounted Russian oil are not only cushioning the blow to itself as a poor energy-importing country, but also helping to prevent even more economic pain for Europe. If the 4.3 mbpd of crude oil that Russia sold to the West last year (or six mbpd including oil products) had no alternative markets like India, the world oil price would be even higher.

Recognising the importance of keeping Russian oil on the market, the G7 has now come up with an alternative sanctions strategy that could present India with its next big test. The West’s Plan A was to combine, by the end of 2022, a partial embargo on direct imports of Russian oil with an attempt to choke off Russian oil exports to third countries by leveraging Western (and especially British) dominance of the global marine insurance market.

Plan B is the so-called ‘price cap’ mechanism. This would allow Russia to continue exporting oil but set a maximum price just sufficient to cover its production costs, thereby depriving the Russian state of any war-financing rent.

When the price cap scheme was first officially aired at the G7 summit in June, several leaders, notably German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, publicly questioned its viability—especially regarding compliance by third-party buyers of Russian oil. Even if Russia agreed to the cap, who would get access to its deeply discounted oil, and who would pay the full market rate? Russia would be much more likely to simply reduce output, hoping to offset its losses with the resulting further price surge for whatever residual oil exports evaded the Western insurance net.

Either way, India will be in a pivotal position. While Russia’s opaque oil sales to China will continue regardless, India can look forward to various arbitrage opportunities. It will continue importing substantial quantities of Russian oil at ever cheaper prices. And in the event that such imports weakened Western measures to squeeze Russia’s oil rents, the US would be unlikely to threaten—much less impose—secondary sanctions on India.

After all, successive US administrations—under presidents Donald Trump and Joe Biden—have refrained from using their legal powers under existing legislation to place secondary sanctions on India for continuing to buy Russian weapons. The reason for this is clear: a closer security partnership with India has become a vital part of America’s China policy. The Quad—an informal security grouping comprising the US, Japan, Australia and India—has emerged as a cornerstone of US Indo-Pacific strategy, and would not survive the US sanctioning one of its members.

Of course, the US–India security relationship is mutual, given the live Chinese threat to Indian territory along the Himalayan Line of Actual Control—as the deadly June 2020 border skirmish showed. But India’s fear of China also implies a strategic dimension to its ties with Russia that goes well beyond opportunistic oil and arms purchases. India has an interest in keeping Russia close and not allowing a monolithic and estranged Russia–China Eurasian axis to loom over the Indian subcontinent.

India is playing this multifaceted game adroitly. In defence procurement, it has acquired advanced Russian S-400 air-defence systems and agreed to extend until 2031 the licensed local production of Russian weapons. But it has also increased arms purchases from NATO members, notably France.

India has ample options for managing broader US sensitivities vis-à-vis Russia. Russia urgently needs to replace industrial inputs that it previously imported from the West. This could provide further opportunities for Indian exports, which are already a third higher than their pre-Covid-19 level, owing in part to the government’s Atmanirbhar Bharat (‘self-reliant India’) stimulus program for manufacturing. Increased Indian pharmaceutical and automotive exports to Russia need not involve military support of the kind that has already led the US to sanction various Chinese electronics manufacturers, as announced on 28 June.

India’s relations with Russia are part of its nuanced and multidimensional foreign policy. This approach means that the 75th anniversary of Indian independence will coincide with the country achieving significant—and advantageous—geopolitical autonomy.

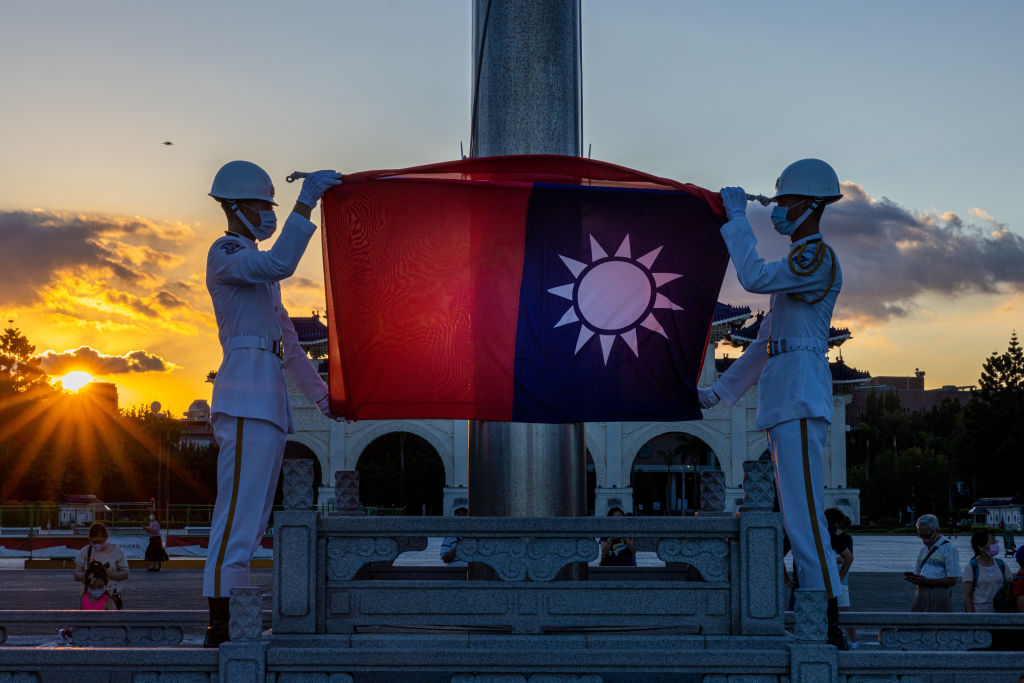

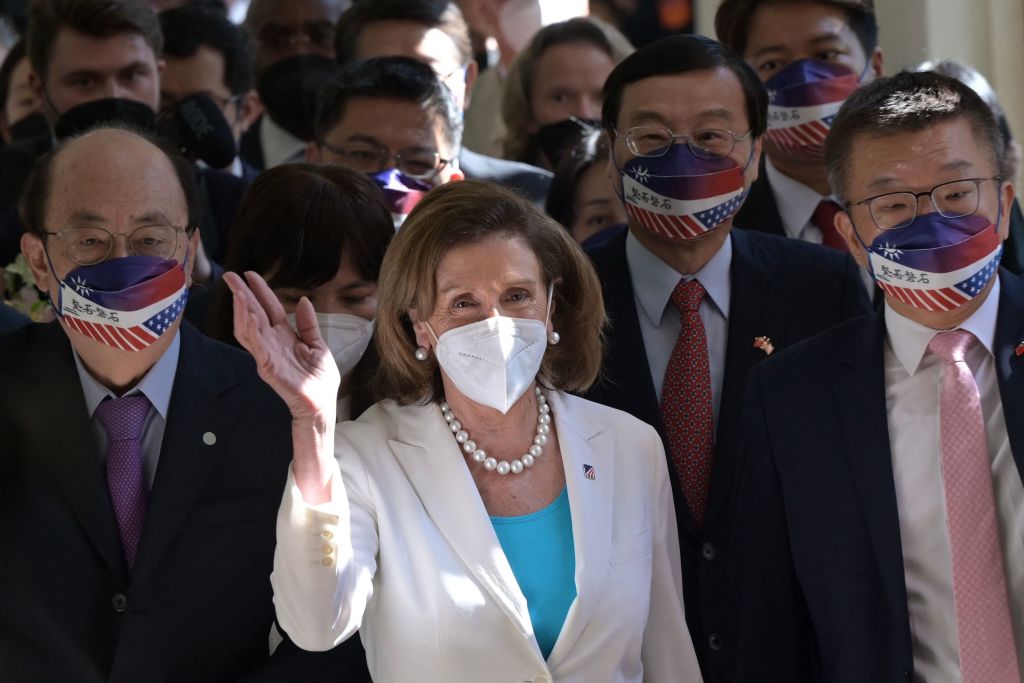

Much of the foreign-policy conversation in the United States over the past two weeks has centred on whether House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi ought to have visited Taiwan. Her backers point out that there was precedent for such a visit—a previous speaker and cabinet members had visited Taiwan—and that it is important for officials to underscore the US commitment to Taiwan in the face of increasing Chinese pressure. But critics argued that the trip was ill-timed, because Chinese President Xi Jinping would likely feel a need to respond, lest he appear weak heading into a critical party congress later this year. There were also worries that the visit might lead Xi to do more to support Russia’s aggression in Ukraine.

But the focus on Pelosi’s visit is misplaced. The important question is why China responded not just by denouncing the trip, but with import and export bans, cyberattacks and military exercises that represented a major escalation over anything it had previously done to punish and intimidate Taiwan.

None of this was inevitable. The Chinese leadership had options. It could have ignored or downplayed Pelosi’s visit. What we saw was a reaction—more accurately, an overreaction—of choice. The scale and complexity of the response indicates that it had long been planned, suggesting that if the Pelosi trip had not taken place, some other development would have been cited as a pretext to ‘justify’ China’s actions.

China’s increasingly fraught internal political and economic situation goes a long way towards explaining Xi’s reaction. His priority is to be appointed to an unprecedented third term as leader of the Chinese Communist Party, but the country’s economic performance, for decades the principal source of legitimacy for China’s leaders, can no longer be counted on as growth slows, unemployment rises and financial bubbles burst. Xi’s insistence on maintaining a zero-Covid-19 policy is also drawing criticism domestically and reducing economic growth.

Increasingly, it appears that Xi is turning to nationalism as a substitute. When it comes to generating popular support in China, nothing competes with asserting the mainland’s sovereignty over Taiwan.

China’s willingness to escalate tensions also reflects its growing comfort with risk and the poor state of relations with the US. Any hope in Beijing that ties might improve in the aftermath of Donald Trump’s presidency has been dashed by President Joe Biden’s administration, which has largely extended the China policy it inherited. Public recriminations are frequent and private dialogues are rare. Tariffs on imports from China remain in place. Xi thus likely concluded that he had little to lose in responding to Pelosi’s visit. His subsequent decision to cut off numerous dialogues with the US—including those on climate change and drug trafficking—demonstrates his comfort with deteriorating relations.

The danger is obvious. With China indicating that its military activities close to Taiwan are the new normal, there is greater risk of an accident that spirals out of control. Even more dangerous is that China will determine that ‘peaceful reunification’ is fading as a real option—in no small part because China alienated many Taiwanese when it violated its commitment to ‘one country, two systems’ after it regained control of Hong Kong. In such a scenario, China may decide that it must act militarily against Taiwan to bring an end to the democratic example Taiwan sets and to head off any perceived move towards independence.

So, what is to be done? Now that China has demonstrated its will and ability to use its increasingly capable military farther afield, deterrence must be re-established. This calls for strengthening Taiwan’s ability to resist any Chinese use of force, increasing US and Japanese military presence and coordination, and explicitly pledging to come to Taiwan’s defence if necessary. It will be important to demonstrate that the US and its partners are not so preoccupied with Russia that they are unable or unwilling to protect Taiwan.

Second, economic relations with China need to be recast. Taiwan and others in Asia, including Japan and South Korea, as well as countries in Europe, have grown so dependent on access to the Chinese market and imports from China that, in a crisis, sanctions might not be a viable policy tool. Even worse, China might be in a position to use economic leverage against others to influence their actions. The time has come to reduce the level of trade dependence on China.

The US also needs a sensible and disciplined Taiwan policy. It should continue to stand by its one-China policy, which for more than 40 years has finessed the ultimate relationship between the mainland and Taiwan. There is no place for unilateral action, be it aggression by the mainland or assertions of independence by Taiwan. Final status will be what it will be; what should matter from the US perspective is that it be determined peacefully and with the consent of the Taiwanese people.

A concerted effort to build a modern relationship between the US and China is also essential. It is diplomatic negligence, even malpractice, to allow the era’s most important bilateral relationship, which will go a long way towards defining this century’s geopolitics, to continue to drift. Establishing a private, high-level dialogue that addresses the most important regional and global issues, be they sources of friction or potential cooperation, should be a high priority. What should not be a high priority is attempting to transform China’s politics, which would prove impossible while poisoning the bilateral relationship.

Never allow a crisis to go to waste, the old saying goes. The current one over Taiwan is no exception. It is a wake-up call for Washington and Taipei, as well as for their strategic partners in Europe and Asia, and it should be heeded while there is still time and opportunity to do so.

Whatever we make of the visit to Taiwan by US congressional leader Nancy Pelosi, one good thing to come out of it is that Australians have a much clearer sense of President Xi Jinping’s determination to take Taiwan by force.

Let’s hope it doesn’t come to that. Still, it’s probably better we get the message sooner rather than later.

Now that we have heard the warning, what can Australia do about it?

Australia’s formal responses to Beijing’s military reactions have been tightly constrained by the terms of our relations with China.

Foreign Minister Penny Wong expressed concern over Beijing’s disproportionate military response to what was, when all is said and done, a civilian initiative on Pelosi’s part.

Defence Minister Richard Marles pointed to China’s violation of the UN-sanctioned law of the sea and to Australia’s long-standing commitment to upholding freedom of navigation and commerce in the region.

Neither Wong nor Marles questioned China’s claim to the territories of Taiwan—the core claim underpinning Beijing’s determination to take the island by force.

This is because Australia recognised the Beijing government as the sole legitimate government of China in 1972, and as a condition of recognition declined to recognise Taiwan as a sovereign state.

Like all serious players, we keep our word. In mounting limited objections to China’s behaviour, Wong and Marles echoed the positions of the EU, the US and all members of the G7 that there has been no change in respective one-China policies or basic positions on Taiwan, despite Beijing’s claims to the contrary. We are sticking to our side of the bargain.

In the 1970s, those agreements focused on territory and said little about people. What do people in Taiwan want?

Surveys of Taiwanese show a pragmatic preference for retaining the status quo over seeking formal independence, because under the status quo people enjoy civil liberties, rule of law, political rights, economic autonomy and a way of life won through decades of strife and struggle on Taiwan.

Seeking formal independence would place those rights and liberties at risk, in face of Beijing’s threats of violent retaliation. But so would voluntary unification with the People’s Republic.

Beijing’s treatment of Hong Kong in 2020 shattered any remaining illusions over the fate of Taiwan under Beijing’s ‘one country, two systems’ model of inclusion. On Xi’s new model, the people of Taiwan would be ‘re-educated’—China’s ambassador to France revealed this week—in the style of Mao Zedong’s gulags or Xi’s mass internment camps.

Here’s the rub. The CCP says it is prepared to pay any price to fulfil its historical mission of unification with Taiwan, but the one price it won’t consider is the one it would cost to incorporate the territory peacefully: allow people in China to enjoy the same rights and liberties that people have in Taiwan.

The upshot is that in place of reforming his own country, Xi is preparing to take the island by force against the wishes of the people of Taiwan.

The message conveyed by his ballistic missiles is that Beijing could fly right over the heads of people on Taiwan and lay claim to their lands without giving them a passing thought.

In effect, China now seeks ‘vacant possession’ of the island, in the memorable phrase of journalist Rowan Callick, and Australia never signed on to that.

Australia did not sign on to a lot of things that China does as a matter of course in the new era of Xi.

We did not promise to remain silent on Tibet, where the Chinese Communist Party is working energetically to erase the languages, cultures, religion and identities of local communities to retain a stranglehold on their ancestral territories.

Australia never agreed to Beijing perpetrating cultural genocide against Uyghurs and other minorities to maintain its grip on their historical territories in Xinjiang.

We did not sign on to the crackdown in Hong Kong that put an end to rule of law, civil society and freedom of speech and assembly once Beijing decided to extend direct control over that territory as well.

In acknowledging Beijing’s one-China position, Australia never conceded Beijing’s right to coerce, corral and ‘re-educate’ the people of Taiwan. In Beijing’s eyes, territory comes before people, and that was never part of the deal.

There is much that can be done to help the people of Taiwan without breaking our word.

Canberra can accelerate negotiations on bilateral economic agreements with Taipei and support its inclusion in multilateral economic agreements. We can actively support its participation in international organisations, including key agencies of the World Health Organization.

Federal and state governments should give added encouragement to cultural and educational exchanges with Taiwan.

Australians can reach out to people in Taiwan through their church groups, and by way of community and business associations, trade unions and local governments, to reassure their counterparts in Taiwan that they are not alone in confronting intimidation and interference from the CCP.

Through travel and everyday communications, we can let the people of Taiwan know we have their backs.

Australians have as much reason to be wary of China’s communist government as people in Taiwan, because China’s communists have shown they don’t care about people anywhere—not in China, not in Taiwan and not in Australia.

That much we knew before Pelosi visited Taiwan.

Like his strategic partner Vladimir Putin in his horrific war in Ukraine, Xi Jinping’s violently aggressive actions in the past few days against Taiwan—and Japan—have revealed how he wants to act in the world.

These acts are what diplomats and governments have called ‘disproportionate and destabilising’.

Despite the strident efforts of China’s wolf-warrior diplomats, it’s plain hard for Beijing to portray itself as the victim here. Victims are usually not the ones launching ballistic missiles when others aren’t.

The military violence is far from a reasonable response to the visit to Taiwan of an 82-year-old American politician called Nancy Pelosi.

China’s ambassador to Canberra, Xiao Qian, did his best to follow the instructions from Xi, repeating foreign ministry lines. ‘The actions taken by Chinese government to safeguard state sovereignty and territorial integrity and curb the separatist activities are legitimate and justified. Instead of expressing sympathy and support to the victim, the Australian side has condemned the victim along with the perpetrators.’

But in the real world, Chinese military aggression shows us that Beijing is intent on changing the peaceful status quo across the Taiwan Strait—something that is a flat contradiction to China’s stated policy of wanting peace.

Chinese military planes and ships closing large areas of the air and maritime space around Taiwan and the People’s Liberation Army firing ballistic missiles over the heads of 23 million Taiwanese people and into Japan’s exclusive economic zone are a physical demonstration of China’s intent. These actions make its words about peace and stability empty.

It’s surprising that no one in Beijing or in the PLA higher command seemed to consider the effect on Japanese policy and public opinion that’s flowing from the disastrous decision to launch ballistic missiles into Japan’s EEZ. If China had wanted to really energise Tokyo’s efforts to strengthen Japan’s military power and to think through the close connection between Taiwan’s security and its own, these missile launches would have been the best way of achieving that.

Xi went beyond even the military violence, adding other overreactions like ending climate talks and military contact with the US, cancelling a meeting between the Chinese and Japanese foreign ministers and threatening the EU if members of the European parliament visit Taiwan.

This lack of control from the Chinese also shows us something important about what happens next in nations’ relationships with Taiwan.

Xi’s violent overreaction to a political visit demonstrates how determined Beijing is to isolate Taiwan from the rest of the world. That is probably the biggest implication to draw from the past few weeks.

Beijing’s primary goal with all the heat, light and aggression is to raise the costs of future engagement with Taiwan by all politicians from every democratic country and every government other than its own.

Beijing wants us all to self-censor our engagement with Taiwan to avoid more of these disproportionate reactions. That’s so important because Xi and his military want to have a free hand to act against Taiwan and its people at a time of his choosing.

So, if the US, the EU and its members, Japan, the UK, Australia and even ASEAN members want actual peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait, one of the primary ways of getting that is continued—and increased—political and economic engagement with the Taiwanese government, people and economy. That raises the costs to Xi of ordering an attack on Taiwan and it also provides political support for the Taiwanese government and people.

This engagement will show Xi something he already fears is true: using force against Taiwan is against the interests of many governments and peoples. It is not what he would like it to be—an internal matter for the Chinese Communist Party to determine.

Xi’s direction of violence against Taiwan and Japan in the past few days has driven some interesting responses from different parts of the world. The G7 grouping—made up of Germany, France, Italy, Japan, Canada, the US, the EU and the UK—clearly identified Beijing as the source of destabilising aggression around Taiwan and called on China to de-escalate its military actions.

The US, Japan and Australia all issued measured, calm statements separately and as a group that also plainly identified China’s aggression as destabilising and disproportionate.

Even a reluctant ASEAN put out a quietly worded statement that disagreed with Beijing’s core propaganda around its one-China principle, stating, ‘We reiterate ASEAN Members States’ support for their respective One-China Policy.’ Decoding this diplomatic note, the reference to ‘their respective One-China policy’ was ASEAN quietly but firmly dissenting from Beijing’s line that everyone has accepted its particular definition of ‘one China’—which is that Taiwan is an inalienable part of the territory governed by Beijing.

Like Australia, and many other nations, ASEAN states simply do not and have not signed up to China’s view of the world on this critical issue.

Australia, like many, maintains the same policy that Prime Minister Gough Whitlam put in place back in 1972 when China and Australia established diplomatic relations: ‘The Australian Government recognises the Government of the People’s Republic of China as the sole legal government of China, [and] acknowledges the position of the Chinese Government that Taiwan is a province of the People’s Republic of China.’

Critically, Australia acknowledged it is the PRC government’s view that it has jurisdiction over Taiwan—but, beyond acknowledging it, we have never agreed with that view. We do, however, support peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait and reject anyone acting unilaterally to change the status of Taiwan by force.

And, stripping back all the words and focusing on who has done what to whom around Taiwan, it’s the Chinese military that is acting unilaterally in an attempt to change the status quo. This is longstanding policy that predates all the drama about Pelosi and will continue long after this event, because it’s about Chinese strategic ambition, not a reaction to a US politician.

Interestingly, having stoked nationalist fervour and outrage in the lead-up to the visit, China’s propagandists have had a hard time convincing these strident, angry nationalists that their government’s actions were at all meaningful. It’s a demonstration that even a deeply controlling, technologically enabled autocracy like China’s can have trouble responding to its own citizens and may even be forced to act internationally simply because of the domestic energies it has channelled and cultivated. While this often violently expressed nationalism is a direct result of successful propaganda in China’s education system and state media, it is adding to the multiplying domestic pressures and challenges Xi is facing.

Where to from here for Australian policy on Taiwan and for bilateral relations with China? The path seems clearer now than it was when Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s government came to power in May.

On Taiwan and regional security, Australian efforts with allies and partners to raise the costs to Beijing of conflict must intensify.

The defence strategic review ordered by Defence Minister Richard Marles has an obvious and key contribution to make as it finds ways to urgently increase Australia’s military power—a direct contribution to deterrence of conflict in our region.

But this is as much a political and diplomatic issue as a military one, which the government seems to know well. Understanding Beijing’s goal of isolating Taiwan as a precondition for it to then use force to ‘unify’ Taiwan and its people with the mainland makes Australian political and economic engagement with Taiwan more important.

By deepening political and economic engagement with Taiwan, Australia will be working in concert with partners and allies across the Indo-Pacific and in Europe. One example is Japan, with the week’s events only accelerating an already deepening strategic partnership with Australia.

Australia and other partners can also work to have Taiwan included in more international organisations and forums, engage in security discussions with Taiwanese officials, and work with Taiwan on strengthening cybersecurity and countering coercion and disinformation activities.

All this is entirely possible within the one-China policy Australia adopted in 1972. It’s entirely impossible within the one-China policy Beijing is working so hard to tell us we have.

A key part of engagement with Taiwan that Beijing will pretend not to understand is for it to happen just like democracies work internally—in a messy and organic way that allows diverse people and views to express their opinions and act without government direction. So, political visits to Taiwan must not just increase, but be communicated to be what they are: the choices of individuals living in freedom in democracies—and not subject to veto by presidents or prime ministers.

This contrasts with what Xi and Putin told us they wanted in their joint statement back in February: a world where these two leaders dictate the choices of other nations by force if necessary and where other governments self-censor themselves and their populations for fear of the consequences from Beijing and Moscow. This goes to the heart of the real competition with Xi and Putin, which is about how our societies and the world work.

Beijing’s anxiety about this kind of policy direction from governments with connections to Taiwan is already obvious. The future will be a tense one because Chinese strategists and military planners have an object lesson in what this kind of unity can do when they look at the political and military support Ukraine is receiving to fight the war Putin’s miscalculation has inflicted on Europe.

For those who see tension as inherently bad, the alternative to managed tension with Beijing over Taiwan is a future in which we all watch the type of horrific killing and destruction we are seeing in Ukraine occurring in Taiwan as China’s military attempts to conquer 23 million people living in freedom in the vibrant democracy that is Taiwan.

As for Australia’s relations with Beijing, the false dawn that the Chinese ambassador dangled before the new Australian government has already ended. That’s because China is now far less a bilateral relationship for Australia than an increasingly obvious common strategic challenge for every nation affected by Beijing’s use of power. And the strategic partnership between Putin and Xi joins Europe’s security with the security of our own region in new and direct ways.

Our policy must be informed by the knowledge of this common challenge and the unity and power that it brings to common efforts between Europe and the Indo-Pacific. That’s just as important to communicate to the Australian public as it is as a foundation for policy and action.

As Australia’s space sector grows and continues to build significant sovereign capabilities, optimising the links between the commercial and national security space sectors is critical. ASPI’s Bec Shrimpton speaks to Adam Gilmour, CEO and founder of Gilmour Space Technologies, about the need for greater collaboration between the private sector and government to support Australia’s space industry.

It’s been more than two years since the deadly clashes on the India–China border in 2020, and despite many rounds of consultations between the two countries, the situation shows no signs of improving. ASPI’s Baani Grewal speaks to Tanvi Madan, senior fellow in the Project on International Order and Strategy in the foreign policy program and director of the India Project at the Brookings Institution, about the trajectory of the India–China relationship in light of the border issues, as well as the differences between India’s participation in the Quad, BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation.

Southeast Asia continues to see a rapid digital transformation, fuelling the region’s economic growth. ASPI’s Gatra Priyandita talks to Elina Noor, director of political-security affairs and deputy director of the Washington DC office at the Asia Society Policy Institute, about how governments in Southeast Asia are responding to the region’s digital transformation.

US Vice President Kamala Harris appeared virtually at the Pacific Islands Forum leaders’ summit in July to announce a new wave of US assistance to ‘significantly deepen’ US re-engagement in the region. But if Harris made waves in Suva, there was barely a ripple by the time the news spread across the vast ocean to the outer islands of Pacific countries.

If the US and the other members of its Partners in the Blue Pacific initiative—Australia, Japan, New Zealand and the UK—are to have an impact, they need to better understand online and social media information flows so they can speak to, understand and demonstrate that they’re meeting the priorities of the region.

Partners in the Blue Pacific is supposed to be an inclusive, informal mechanism to enhance cooperation in support of Pacific island priorities. But the partners also need to invest time and energy in communicating what assistance is actually being delivered, and they need to do it in a way that reaches and makes sense to Pacific people.

The recent Pacific Islands Forum summit was an example of a prime messaging opportunity that didn’t reach its full potential.

Initially, the chair of the forum, Fijian Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama, uninvited all 21 of its dialogue partners—including China, Japan, the UK and the US—in an attempt to stop geostrategic competition from distracting Pacific leaders from their core agenda.

But on the third day of the event, Harris announced her administrations new plans, which include tripling funding for economic development and ocean resilience in the Pacific to US$60 million a year for 10 years, establishing new embassies in Tonga and Kiribati, and re-establish a USAID regional mission in Suva.

The US announcement didn’t get the traction it deserved with the broader population through online media. It’s not the first time that has happened. Unfortunately, it also won’t be the last.

That’s because the countries that make up the Partners in the Blue Pacific don’t always tell the story right.

Storytelling is an essential part of Pacific island cultural knowledge and information sharing. More needs to be done to engage local media and to help tell the story of how aid, assistance and improving people-to-people links affects each country, island or group.

In an ASPI study of news and social media in the Pacific over the two weeks when the meetings in Suva were taking place, our analysis showed obvious differences between locally written and US-origin articles. The study used a simple categorical sentiment analysis of relevant social media comments that are targeted at foreign countries or local governments. Each comment was categorised as either positive or negative.

Articles written in the US resulted in a positive-to-negative comment ratio of 0.25. That means that for every positive comment there was about the US announcements, there were four negative ones.

For articles written locally, the ratio was 1.27. So, for the same four negative comments, there were just over five positive ones.

This comes from a relatively small sample size, however. There were only 459 Facebook comments in total across 171 articles reporting on the forum. Around 10% of comments were focused on the US, aligning with the 12% of articles that focused on the US announcements.

Regardless, the benefits of engaging local media are obvious. Only half of the articles on the US assistance announcements were produced by local journalists. The US announcements and geostrategic competition in the region were the topics with the lowest percentages of locally written articles emerging from the forum.

Finally, if the US and its partners needed one more reason to engage local media, they could look towards the Chinese Communist Party’s failed attempts to push narratives of American militarism and Australian paternalism in the region.

During the two-week collection period for this study, we identified 20 editorials in CCP state media relating to the Pacific Islands Forum, pushing a combination of pro-CCP propaganda and anti-Western narratives.

Highlighting how these narratives—written and published in China—lack relevance to the region, only one article attracted more than a handful of comments in Pacific island public Facebook groups. In this small sample, Pacific islanders consistently expressed scepticism and resentment of foreign interference in their affairs.

The population’s visible frustration with Chinese messaging online, as determined by our sentiment analysis, is echoed by Pacific leaders offline. The forum’s secretary-general, former Cook Islands prime minister Henry Puna, outlined the importance of listening to Pacific voices when he said, ‘If anybody knows what we want, what we need, and what our priorities are, it’s not other people, it’s us.’

The next test for Pacific partners will come this weekend when the new US ambassador to Australia, Caroline Kennedy, visits Solomon Islands.

In May, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi failed his test when a press conference he held in Honiara was boycotted by Solomon Islands journalists who claimed that the CCP was ‘impeding on democratic principles’ when it sought to limit access and questions.

The US wouldn’t ever make that mistake, but it can still do more to engage local media—for example, by giving exclusive interviews to members of the Solomons’ media association. Following the recent tightening of government control over the Solomon Islands Broadcasting Corporation, giving power to the local voice has never been so important. And it is the local voice that will be integral to how the US is perceived and understood in Solomon Islands.

The Labor Party’s pre-election promise of a defence force posture review has now taken shape as a much more expansive strategic review encompassing the Australian Defence Force’s structure, posture and investment requirements over the next 10 years and beyond. Listen carefully and you’ll hear the gentle noise of a white paper being prepared.

The review will be headed by two independent leads, former Labor defence minister Stephen Smith and former ADF chief Angus Houston, and will report to the National Security Committee of Cabinet by March next year, alongside the release of the findings of the investigation of alternatives for acquisition of an Australian nuclear submarine capability announced under the 2021 AUKUS agreement.

The terms of reference make it clear that this review will consider not only the posture of ADF units, but also ‘force disposition, preparedness, strategy and associated investments’ required to achieve a force that is fit for purpose in a more adverse strategic environment. It will build on the analysis of trends set out in the 2020 defence strategic update and force structure plan, which in turn were hinted at in the 2016 defence white paper.

The review will first need to ‘outline future strategic challenges facing Australia’. That will demand a robust treatment of the challenge posed by a rising and assertive China. The threats from China are taking the form of not only a much more capable and modernised People’s Liberation Army, but also a more assertive use of grey-zone tactics by Beijing, the application of direct political warfare against Australia, and a creeping expansion of Chinese influence and presence into Australia’s area of direct military interest, including the South Pacific.

Past defence white papers have invariably seen their analysis rapidly overtaken by events. This is certainly what happened with much of the strategic assessment from the 2016 white paper. The accelerating deterioration in our strategic environment, which has been underway since 2015, prompted the 2020 update to go further to address the challenge from China. But that challenge has grown markedly even in the two years since the update’s release.

The evidence is clear, with aggressive PLA actions against Australian ships and aircraft in international waters, and the prospect of a Chinese military presence in the Solomon Islands—not to mention the rising danger of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, perhaps as early as the second half of this decade. The PLA’s ability to project power at long range has also grown. China now has more advanced missile systems, strategic air power and counterspace and cyberwarfare capabilities. It has a bigger and more capable navy, and a large-scale nuclear build-up is underway.

To meet this challenge, the ADF needs to embrace a more forward-orientated posture that emphasises and hardens its capability in northern Australia. The notional sea–air gap in the north, which first appeared as early as the 1986 Dibb report, will have to be seen as a main rear area from which the ADF projects its operational focus—rather than from the south of the continent. That would be a significant shift in force posture, which I first suggested in 2018.

A ‘forward defence in depth’ strategy would involve expanding the ADF’s northern posture as well as building closer defence relations with key Indo-Pacific partners such as Japan, South Korea, India and some of the ASEAN states. It also entails strengthening Australia’s burden-sharing with the United States, including by allowing enhanced access for US forces to defence facilities in northern Australia—a step already suggested in last year’s AUSMIN communiqué.

In terms of force structure, priority needs to be given to expanding, enhancing and accelerating the acquisition of an ADF strike and deterrence capability. The review should not simply reiterate the 2020 force structure plan, and nor should it simply rely on the very long-term acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines to provide enhanced military capability. It needs to recognise the importance of acquiring truly long-range power projection for the ADF. It also needs to contend with that fact that air and naval platforms such as the F-35A Lightning II, F/A-18F Super Hornet and Hobart-class air warfare destroyer are likely to face increasingly greater risks in penetrating deeply inside China’s growing anti-access/area-denial envelope to deliver standoff weapons. Longer range platforms to deliver longer range missiles with precision and speed will be essential.

Ideally, Australia would have forward host-nation support in any crisis, but we can’t assume that’s always going to be available. Projecting strike capabilities directly from northern Australia to hold at risk any maritime threat generated by a major-power adversary like China, well beyond the notional sea–air gap, would dramatically boost the ADF’s ability to deter and respond, as well as to burden-share with key allies. There needs to be a discussion about acquiring in-development B-21 bombers and long-range conventional ballistic missiles that can strike at both land and maritime targets.

Related to this challenge are maximising the weight of fire to generate useful effects and sustaining combat in a possible conflict with China, which could easily become a protracted war. Part of the solution could be a far more ambitious and fast-moving autonomous systems strategy. But combat sustainment is a key weakness for the ADF, with its brittle and boutique platforms and munitions. A force structure that has both mass and endurance will be what’s required in a future war.

Earlier this year, the former government sought to accelerate the guided weapons and explosive ordnance enterprise as part of AUKUS, but so far little has happened beyond the choosing of two large aerospace prime contractors to lead the project. There’s been scant information on what weapons are to be built, how many and how fast, and when those weapons will start flowing. Building small numbers of weapons will be insufficient to meet the demands of high-intensity warfare, a fact so clearly demonstrated in the ongoing war in Ukraine. Nor does Australia have the luxury of time to build small stockpiles slowly.

The review is also tasked with considering funding and investment both for force structure and for preparedness and mobilisation. It’s vital that this is a strategy-led—not fiscally-led—exercise. The review must decide what the threat is and how to meet it in a manner that best protects Australia from emerging long-range capabilities and, in particular, neutralises the risk posed by Chinese military bases in our near region.

Deterring Chinese adventurism—be it against Taiwan, in the South China Sea or across the South Pacific—and responding to the threats posed by Chinese military capabilities must drive the review. This goal must also shape the review’s assessment of force structure requirements and its promotion of the case for a stronger and more robust ADF presence in northern Australia. Then it can work out how much extra spending will be needed to meet these goals. National security and defence will need to come first and the money will need to be found. The alternative is to accept a more insecure future.

A review that advocates a steady-as-she-goes, more-of-the-same approach in the face of a much more adverse security outlook will be a failure. Now is the time for the government to grasp the extent of the challenge posed by a rising China to our nation and our region and respond with responsible and decisive changes to Australian defence policy.

On 14 July, after months of controversy, Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare publicly ruled out the possibility that his security pact with Beijing would result in a Chinese military base in his country. Many Indo-Pacific nations no doubt welcomed his assurance that ‘there is no military base, nor any other military facility or institutions, in the agreement’.

In Canberra, many will have welcomed Sogavare’s declaration that Australia remains the ‘security partner of choice’ for Solomon Islands. However, his comments that his government would only call upon China if there were a gap Australia couldn’t meet is telling. His warm greeting of Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese was equally telling.

Like most politicians, Sogavare aspires to prevail over his opponents and stay in power. However, he faces mounting domestic challenges, including declining public trust in his government.

Domestic law-and-order problems present a genuine risk to Sogavare’s leadership. In November, he refused to meet with protesters from the province of Malaita, which led to serious riots that caused widespread damage in Honiara. A month later, he faced a vote of no confidence, which he easily defeated. Sogavare quickly linked the riots with Taiwanese influence (in 2019, he decided to switch recognition from Taiwan to China, which Malaita has opposed ever since).

But Sogavare, unlike leaders of the ilk of Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen, doesn’t harbour aspirations to leave a leadership legacy or dynasty. Instead, his motivations are far more modest. He wants to maintain his power and control over the island nation. His strategy to achieve that has both external and internal dimensions.

Externally, he seems set to ensure that money and aid from the East and West continue to flow to Solomon Islands. In doing so, he will continue to exploit opportunities as they arise. For now, Chinese money is flowing. And he has Canberra worried that if it doesn’t provide the security he needs, China will be waiting in the wings.

Internally, Sogavare is moving to cement his control over his opposition. Like with Cambodia’s Hun Sen, these manoeuvres include controlling the domestic media. Last month, Sogavare transferred control of the state-owned broadcaster SIBC’s budget directly to the government. SIBC has now been ordered to only publish favourable news about the Solomons government.

On Monday the ABC reported that Sogavare, like Hun Sen, has been able to access Chinese funding to support his grip on power. The ABC obtained access to documents that indicate a ‘Chinese slush fund was activated twice last year and dispersed nearly $3 million directly to members of parliament loyal to the Prime Minister’.

Sogavare has shown consistent disdain for international media, including the ABC, refusing to engage with them.

Experience in Bougainville and Solomon Islands has shown that in the absence of independent media, local communities will be informed by rumours.

It’s no accident that Sogavare has accepted the offer of police training from China. He also made a statement regarding a more permanent Chinese police training presence. In contrast with Australia’s approach to policing, the priority for China’s police is protecting the Chinese Communist Party. A loyal praetorian guard is a necessary tool for a leader facing increasing opposition while focused on prevailing.

Sogavare would do well to remember that Solomon Islanders have a deep cultural memory of colonial-era policing. Recent history has also shown that aggressive policing fails to quell riots. In some cases, aggressive policing in Solomon Islands has promoted further civil unrest. While this doesn’t bode well, Sogavare isn’t keen for Solomon Islands to become a vassal state of China. That would prevent him from playing every side to get the best deal.

While money does talk in the Pacific, strong relationships are built over time. Australia is fortunate that its police have worked closely with their Solomon Islands counterparts for decades. From commissioner to recruit, Solomon Islands police know that Australian police are their partners. Of course, China’s policing aid, including the gifting of equipment and training, will continue. China will also, in time, likely provide Solomon Islands with a police academy.

Australia’s long-term law enforcement cooperation with Solomon Islands, including its 14-year-long regional assistance mission from 2003 to 2017, has profoundly impacted the nation’s police. The police force has moved from being concerned with policing the people and protecting the state to serving the community, but this positive shift could be easily undone through Sogavare’s pact with China.

Neither Australia nor any other country should try to outspend China in Solomon Islands. But we should be looking for opportunities to deepen our relationships. Solomon Islanders, and their police, want community policing, not security policing. Australia should seek opportunities to increase cooperation and capacity-development activities through the Australian Federal Police and the Australian Border Force. Both agencies should look for opportunities for Solomon Islands police to attend specialist and leadership courses with their Australian counterparts. Australia should look for opportunities to continue assisting with the development of Solomon Islands police training programs. Where appropriate, Australia should provide the kinds of capabilities that help with community policing.

Regardless, China, like Australia, must deal with Sogavare’s opportunistic nature. China has a security pact with Solomon Islands, but the conditions on the ground can and will change regularly. Australia, with its long-term relationships and principles-based approach, is in a far better position to navigate the ebb and flow of this challenge than China.

Australia’s recent change of government provides a useful opportunity to reflect on the problems of the South China Sea and the way ahead for our national policies. In a sense, the clear continuity between the approach of the last government and, so far, that of Labor confirms the need to consider matters both in their wider strategic context and for the long term. As a strategic problem, the South China Sea isn’t going to go away.

Why does the South China Sea matter for Australia? Because to accept China’s claims to it not only undermines fundamental elements of the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea but acquiesces to Chinese coercion through the use of armed force. Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2014 and its more recent attack on Ukraine are compelling examples of what uncontested ‘learned bad behaviour’ can go on to become.

Australia must be there for the long haul. It needs to assert its independent national interests and its national presence in the region. On the other hand, Australia must work not only with the United States but, and this will be increasingly important, its regional (and extra-regional) partners to minimise its and their vulnerabilities and maximise the pressure on China.

The South China Sea is as much a contest of information and ideas as a cockpit of at-sea and in-the-air encounters. For Australia, that contest has both domestic and international aspects. Continuing education of a shore-bound and ground-based—and sometimes less than expert—media and commentariat will be required to inform the Australian public. Australia’s strategic narrative must highlight its commitment to a stable region, why that commitment matters and its record in building and supporting it.

Making an effective case for the South China Sea not to become a ‘closed sea’ is fundamental. So are clarity and consistency. Most notably, distinctions between ‘shadowing’ and ‘harassment’ must be made clear. The People’s Liberation Army Navy and China’s maritime air arms have just as much a right to range freely as our own forces. Australian and allied units can expect to be monitored by Chinese ships anywhere within the ‘first island chain’ and possibly elsewhere, but if the Chinese presence doesn’t interfere with our operations, it must be not only regarded but openly acknowledged as legitimate. As should be any professionally conducted shadowing of Chinese units by Australian forces in our own areas of interest.

Only when PLA units operate in an unsafe way or prevent our forces from carrying out their intended operations should loaded terms such as ‘harassment’ and ‘aggression’ be employed. To be fair, since 2018 it appears the PLA Navy has generally conducted itself responsibly on and below the surface. It’s no coincidence that the 2014 Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea, a document accepted by China, speaks of ‘Actions the prudent commander might generally avoid’, something that has not been agreed for China’s maritime militia units or, potentially most critically, units of the PLA’s air arms. Recent events have highlighted the special potential for encounters in the air to go badly wrong, with serious, immediate and potentially fatal consequences. An aircraft falling out of the sky is a more serious matter than ships riding each other off.

Australia’s operational and tactical concepts must thus encompass worst-case scenarios. The need for cover—that is, to have forces of sufficient capability and/or in reasonable proximity to deter aggressive actions—is a key consideration. There have been calls for different approaches to asserting Australia’s presence. Such ideas have merit, although implementation would be very complex, particularly those involving closer cooperation with some of the littoral states.

Contingency plans must be ready for when things do go wrong. In particular, the information components of such plans must come into play straight away. Getting the message out to the world about Chinese aggression cannot wait. China was clearly blindsided by the speed with which the Americans uploaded critical video footage to the internet after the USNS Impeccable incident in 2009, footage which made clear that the Chinese fishing boats involved were provocateurs and not victims of the American surveillance ship. Commanders need to have the authority to publish such video evidence without delay. Arguably, airborne units should be transmitting audio and video at all times.

China itself must be a target of our educational effort. Its attempts to paint Australia’s presence in the South China Sea as alien and aggressive must be constantly refuted. A regime which has made so much of the centenary of the establishment of the Chinese Communist Party cannot lightly dismiss Australia’s record over much the same period, however ancient China’s civilisation. Also, considering that Darwin is closer to Singapore than is Shanghai, our arguments need not only to emphasise the realities of geography but the interaction between those realities and our security and economic interests as a regional power.

At a time when Chinese scholars are beginning to recognise and lament the atrophy of the time-honoured Chinese virtue of prudence in China’s approach to international affairs, its notable absence in the PLA’s air arms in particular needs to be pointed out. Dangerous behaviour in the air should be described with the scorn it deserves.

The Australian narrative needs to be promulgated in Mandarin and Cantonese as well as in Southeast Asian languages and made as accessible as possible. Australia’s position must be explained and the inconsistences and outright mendacity of much of the Chinese ‘case’ made clear. This information campaign must not only be focused on the strategic level but extend to the operational and tactical.

Finally, Australia cannot sustain a case for the legitimacy of its operations in the South China Sea and other regions if it is as careless with commentary over China’s sallies into Australia’s maritime zones as the then defence minister was during the federal election campaign. Perhaps our requirement can best be described by paraphrasing Theodore Roosevelt. In South China Sea matters, Australia needs to speak carefully and carry a big enough stick.

US House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s arrival in Taiwan has incited a predictably strong response from China. Chinese warplanes have brushed up against the median line dividing the Taiwan Strait. The Chinese foreign ministry has warned of ‘serious consequences’ as a result of Pelosi’s visit to the island. Chinese President Xi Jinping has told US President Joe Biden that ‘those who play with fire will perish by it’. And now, China has announced a major military exercise with live-fire drills starting tomorrow (just after Pelosi leaves Taiwan). The spectre of military confrontation looms large.

But Pelosi is hardly responsible for today’s heightened tensions over the island. Even if she had decided to skip Taipei on her tour of Asia, China’s bellicosity toward Taiwan would have continued to intensify, possibly triggering another Taiwan Strait crisis in the near future.

Contrary to the prevailing narrative, this is not primarily because Xi is committed to reunifying Taiwan during his rule. Although reunification is indeed one of his long-term objectives (it would be a crowning achievement for both him and the Chinese Communist Party more broadly), any attempt to achieve it by force would be extremely costly. It might even carry existential risks for the CCP regime, the survival of which would be jeopardised by a failed military campaign.

For a Chinese invasion of Taiwan to have a good chance of succeeding, China would need first to insulate its economy from Western sanctions and acquire military capabilities that can credibly deter an American intervention. Each of these processes would take at least a decade.

The main reasons for China’s current sabre-rattling over Taiwan are more immediate. Chinese authorities are signalling to Taiwanese leaders and their supporters in the West that their relations with one another and with China are on an unacceptable trajectory. The implication is that if they do not change course, China will have no choice but to escalate.

Until relatively recently, China’s leaders viewed the situation in the Taiwan Strait as unsatisfactory but tolerable. When Taiwan was ruled by the traditionally China-friendly Kuomintang (KMT) party, China was able to pursue a gradual strategy of economic integration, diplomatic isolation and military pressure—one that it believed would eventually make peaceful reunification Taiwan’s only option.

But in January 2016, the pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party returned to power in Taiwan, upending China’s plans. While the KMT claims that Taiwan and China have different interpretations of the 1992 Consensus—the agreement the party reached with mainland Chinese authorities 30 years ago asserting the existence of ‘one China’—the DPP rejects it altogether.

Though it is difficult to pinpoint precisely when the new status quo became intolerable to China, a key turning point probably came in January 2020, when Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen of the DPP easily won a second term, and when her party trounced the KMT in legislative elections. As the DPP solidified its political dominance, China’s dream of achieving peaceful reunification moved further out of reach.

It also did not help that the United States had been gradually shifting its Taiwan policy. Under Donald Trump’s administration, the US lifted restrictions on contacts between US officials and their Taiwanese counterparts, subtly changed the formulation of its ‘one-China’ policy by placing more emphasis on American commitments to Taiwan, and transferred advanced weapons systems to the island. Such challenges to China have continued under Biden. Last year, US marines openly trained with Taiwan’s military. And in May, Biden signalled that the US would intervene militarily if China attacked Taiwan (although the White House quickly walked back his statement).

The Ukraine war also seems to have heightened the sense among Western leaders that Taiwan is in grave and immediate danger. They appear to believe that only robust and vocal support, including high-level visits and military assistance, can avert a Chinese attack. What they fail to recognise is that, viewed from Beijing, their support for Taiwan looks more like an attempt to humiliate China than anything else. It is thus more provocation than deterrent.

China now fears that if DPP leaders and their Western supporters do not pay a price for their affronts, it will lose its grip on the situation. This would not only undermine Xi’s chance of achieving his long-term goal of reunification, it also could invite accusations of weakness that would undermine his standing both within and outside China.

China is probably not planning to launch an immediate and deliberate attack on Taiwan. But it may decide to engage the US in a game of chicken in the Taiwan Strait. It is impossible to predict such a confrontation’s exact form or timing. But it is safe to assume that it would be extremely dangerous, because China believes that only brinkmanship can concentrate all the players’ minds.

Like the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, a new Taiwan Strait crisis might end up stabilising the status quo—albeit after a few hair-raising days. And that may well be China’s plan. But such a gambit could also go horribly wrong. We mustn’t forget that the fact nuclear war did not break out in 1962 was largely a matter of luck.